Stary Służew

Stary Służew | |

|---|---|

City Information System area (neighbourhood) | |

The Krasiński Palace in Stary Służew in 2023. | |

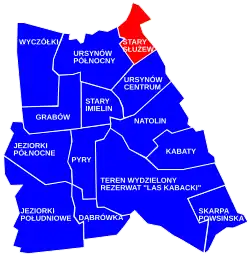

The location of the City Information System area of North Ursynów within the city district of Ursynów. | |

| Coordinates: 52°09′49″N 21°02′43″E / 52.16361°N 21.04528°E | |

| Country | |

| Voivodeship | Masovian |

| City and county | Warsaw |

| District | Ursynów |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Area code | +48 22 |

Stary Służew[a] is a neighbourhood and a City Information System area in the Ursynów district of Warsaw, Poland.[1] It is a residential area, dominated by low-rise single-family houses, with an additional presence of multifamily housing.[2][3] It includes the historical portion of the neighbourhood of Służew, including the 19th-century Krasiński Palace, Catholic St. Catherine Church, and Fort VIII of the Warsaw Fortress.[4][5][6] The campus of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences is also located there.[7]

Służew dates back to at least the 13th century, when it was a small farming community. In 1238 the St. Catherine Church was founded there, with its parish becoming the oldest parish within the current boundaries of Warsaw. It was later rebuilt in the 19th century.[4] In 1245, the village became the property of the knight Gotard of Służew, whose descendants formed the Służewiecki family of the Radwan heraldic clan, who owned this land until the 17th century.[8][9] In 1776, the Krasiński Palace was constructed there.[6][10] Służew was incorporated into Warsaw in 1938.[11][12] In 1956, the campus of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences was established, and was further expanded in the 1960s, 1970s, and 2000s.[13][14]

History

Signs of human settlements from the Stone Age (4000 BCE and 2000 BCE), Bronze Age (3300 BCE to 1200 BCE), and of the Lusatian culture (1300 BCE to 500 BCE) have been found in the area of Warsaw Escarpment and Służewiec Stream.[15]

By 1065, the area was inhabited by the Catholic monks of the Order of Saint Benedict, who founded there their missionary centre. In 1238, the Catholic Parish of St. Catherine was founded by duke Konrad I of Masovia, ruler of the Duchy of Masovia, and erected by bishop Paweł II of Bnin. It is the oldest parish within modern boundaries of Warsaw.[4][16] At the same time, the Służew Old Cemetery was also founded nearby.[17] Archaeological findings suggest that before that, it was a place of worship of Slavic pagans, with signs of fire burning constantly for several hundred years.[18] It is unknown what the first church built there looked like. In the 13th century, a wooden church was built in its place, and was later replaced with a brick structure in the 16th century.[19]

By 1238, the village of Służewo (later known as Służew), was placed near Sadurka river, and owned by the Catholic Order of Canon Regulars of St. Augustin from Czerwińsk nad Wisłą. In 1240, it was acquired by duke Konrad I of Masovia, who then gifted it to his knight and count, Gotard of Służew, on 27 April 1245.[8][9] His descendants became the Służewiecki family of the Radwan heraldic clan, who owned this land until the 17th century.[8][20] The village came into prosperity in the 16th century thanks to selling its grain to Gdańsk. At the end of the 17th century, the village was bought by king John III Sobieski, and incorporated into the Wilanów Estate.[15] In the following decades, Służew changed owners numerous times. Among them, was nobleman August Aleksander Czartoryski, who expanded the agricultural estate of Służew, and financed the rebuiling of the St. Catherine Church in 1742.[19][15] The template was later again rebuilt in 1848, in the Romanesque Revival style.[19]

In 1776, the Krasiński Palace was built Służew. It was commissioned by princess Elżbieta Izabela Lubomirska as a gift for her daughter Aleksandra Lubomirska, and son-in-law Stanisław Kostka Potocki.[6][10] In 1822, it became the property of Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, who organised a library there collecting rare and valuable books. He renamed his estate after his family cognomen to Ursynów, which later inspired the name of the modern city district of Ursynów.[21] The palace was rebuilt in 1860 in the Renaissance Revival style.[22] In 1857, it was acquired by the Krasiński family.[10] Its last owner, Edward Bernard Raczyński donated it to the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Public Education in 1921.[23]

Between 1818 and 1821, Stanisław Kostka Potocki established the Gucin residence near the St. Catherine Church. Following his death in 1821, his wife, Aleksandra Lubomirska founded there the garden complex of Gucin Grove, which was developed between 1821 and 1830.[24] At the turn of 19th century, there were also built catacombs.[25]

In 1864, following the abolition of serfdom in Poland, 44 households received combined land of 342 ha.[15]

In the 1880s, the Fort VIII was built near Służew, as part of the series of fortifications of the Warsaw Fortress, erected around Warsaw by the Russian Imperial Army. It was decommissioned in 1909, and partially demolished in 1913, including all its concrete structures.[26][5]

On 27 September 1938, Służew was incorporated into the city of Warsaw.[11][12]

On 1 August 1944, during the German occupation in the Second World War, a group of civilians was rounded up in Służew, and executed at the nearby Służewiec Racecourse. It was done in the for the unsuccessful attack on the location, organized ealier that day by the Polish resistance, as part of the Warsaw Uprising.[27]

Between 1945 and 1947, the bodies of political prisoners murdered in the Mokotów Prison, were buried in unmarked graves near the St. Catherine Church, by the Security Office. It is estimated that around two thousand people were laid there. They were later exhumed and moved to the nearby Służew Old Cemetery.[28][29] In 1993, the Monument to the 1944–1956 Communist Terror Martyrs, commemorating the victims, was unvailed there.[30]

In 1956, the Council of Ministers gave a plot of land in Służew, as well as in nearby Natolin, Wilanów, and Wolica to the Warsaw University of Life Sciences. The acquired area included the Krasiński Palace and a vocational school near Nowoursynowska Street, which were adopted into the university campus. It was further developed with new faculty buildings throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In 1989, the Krasiński Palace became the seat of the university authorities. Between 1999 and 2002, it was expanded with the construction of a new campus, which became one of the most technologically advanced in Europe. In 2003, all remaining faculties and institutions of the university were moved to Służew. [13][14] Since 1983, the university hosts annually the Ursynalia, one of the largest music festivals in Poland.[31]

In the 1970s, a neighbourhood of single-family housing for the officers of the Polish People's Army was constructed around the Fort VIII. In 1981, concrete-enforced trenches were built in the fort.[5]

In 1994, Służew was divided into two parts, separated by the Dolina Służewiecka Street. The southern, historical part of the neighbourhood became a part of the municipality of Warsaw-Ursynów, while the rest to the north, a part of the municipality of Warsaw-Centre.[32] In 1998, Ursynów was subdivided into the City Information System areas, with the southern neighbourhood becoming part of the area of Stary Ursynów (Old Ursynów). In 2000, it was renamed to Stary Służew.[33][34] In 2002, the municipality was replaced by the city district of Ursynów.[35]

In 1996 the Ursynów Escarpment Nature Reserve, was established in the woodland and swamp on the Warsaw Escarpment, northeastern portion of Stary Służew.[36][37]

In 2019, the Fort VIII was renovated, and turned into a shopping centre.[3] Next to it was opened privately owned recreational Eighth Park (Polish: Ósmy Park).[38] To the north, around Fort Służewiec Street were also constructed several multifamily residential buildings.[3]

Characteristics

The residential areas of Stary Służew are contained within its northern portion. It is dominated by single-family housing, located to the east of Nowoursynowska Street, and with a few houses also located near the Fort VIII.[2] The west of Nowoursynowska Street is also located a small neighbourhood of multifamily residential buildings.[3]

Between Dolinaka Służewiecka Street and Nowoursynowska Street is located the Fort VIII, a historical decommissioned fortification from the 19th century. Currently, it houses the Fort 8 shopping centre.[5][3] Next to it is also located the privately owned recreational Eighth Park (Polish: Ósmy Park).[38]

At 17 Fosa Street is located the Catholic St. Catherine's Church, built in the 19th century, which is the seat of the oldest parish in Warsaw, dating to 1238.[4] There is also the Służew Old Cemetery, which was founded in the 13th century.[17] Additionally, next to the church is placed the Monument to the 1944–1956 Communist Terror Martyrs by Maciej Szańkowski and Sławomir Korzeniowski, which is dedicated to the political prisoners executed by the communist regime between 1945 and 1956.[30]

The southern portion of Stary Służew contains the campus of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences.[7] Among buildings there, at 166 Nowoursynowska Street, is the Krasiński Palace, a historical 19th-century palace, which currently serves as the seat of the university authorities.[6][13] Additionally, the campus hosts annually Ursynalia, one of the largest music festivals in Poland.[31]

The northeastern portion of Stary Służew includes the Ursynów Escarpment Nature Reserve. It consists of a woodland and swamp on the Warsaw Escarpment.[36][37] There is also the historical remains of the Gucin Grove garden complex, including the catacombs.[25][37]

Location and boundaries

Stary Służew is a City Information System area located in Warsaw, Poland, within the northeastern portion of the district of Ursynów. To the north, its border is determined by Dolina Służewiecka Street; to the east, by Wilanów Avenue, Fosa Street, Służewiec Stream, Arbuzowa Street, and around campus of the Warsaw University of Life Sciences; to the south by Ciszewskiego Street; and to the west by Jana Rodowicza "Anody" Avenue and around possessions on Chłapowskiego Street.[1]

It borders Służew, and Stegny to the north, Błonia Wilanowskie to the east, Ursynów-Centrum to the south, and North Ursynów to the west. Its northern and eastern boundaries form the border of the district of Ursynów, bordering districts of Mokotów and Wilanów.[1]

Notes

References

- ^ a b c "Obszary MSI. Dzielnica Ursynów". zdm.waw.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b Studium uwarunkowań i kierunków zagospodarowania przestrzennego miasta stołecznego Warszawy ze zmianami. Warsaw: Warsaw City Council, 1 March 2018, pp. 10–14. (in Polish)

- ^ a b c d e Michał Wojtczuk (13 September 2019). "Takiego miejsca do tej pory nie było w Warszawie, a może i w Polsce. Oto Forteca Konsumpcji". warszawa.wyborcza.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b c d Grzegorz Kalwarczyk: Przewodnik po parafiach i kościołach Archidiecezji warszawskiej, vol. 2: Parafie warszawskie. Warsaw: Oficyna Wydawniczo-Poligraficzna Adam, 2015, p. 364, ISBN 978-83-7821-118-1, OCLC 948875463. (in Polish)

- ^ a b c d Lech Królikowski: Twierdza Warszawa, Warsaw: Bellona, 2002. ISBN 8311093563. (in Polish)

- ^ a b c d Wiesław Głębocki, Tadeusz Kobyłka: Pałace Warszawy. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Sport i Turystyka, p. 52. ISBN 9788321728148. (in Polish)

- ^ a b "Uczelnia". sggw.edu.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b c Józef Kazimierski, Ryszard Kołodziejczyk, Żanna Kormanowa, Halina Rostowska: Dzieje Mokotow. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1972, p. 25–26.

- ^ a b Marta Piber-Zbieranowska: Służew średniowieczny. Warsaw: Towarzystwo Naukowe Warszawskie, 2001, p. 145–150. ISBN 8390732858 (in Polish)

- ^ a b c Marek Kwiatkowski: Architektura mieszkaniowa Warszawy. Warsaw: Państwowy Instytut Wydawniczy, 1989, p. 216. ISBN 83-06-01427-8. (in Polish)

- ^ a b Rozporządzenie Rady Ministrów z dnia 22 września 1938 r. o przyłączeniu części gmin wiejskich Wilanów i Bródno w powiecie i województwie warszawskim do powiatów południowo-warszawskiego i prasko-warszawskiego w m. st. Warszawie. In: 1938 Journal of Laws. Warsaw. 1938. (in Polish)

- ^ a b Marian Marek Drozdowski: Warszawiacy i ich miasto w latach Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej. Warsaw: Wiedza Powszechna, 1973, p. 17. (in Polish)

- ^ a b c "Historia". sggw.edu.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b "Z Marymontu na Ursynów - 200 lat tradycji SGGW". perspektywy.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b c d Wojciech Włodarczyk. "Historia Służewa do lat 20-tych XX wieku". sluzew.org.pl (in Polish).

- ^ A. Sołtan-Lipska (editor): Służew i jego kościół. Warsaw: Church of St. Catherine, 2013, p. 743. ISBN 978-83-938420-0-1. (in Polish)

- ^ a b Karol Mórawski: Warszawskie cmentarze. Przewodnik historyczny. Warsaw: PTTK Kraj, 1991, p. 87-90. ISBN 83-7005-333-5. (in Polish)

- ^ Maria Dąbrowska, Magdalena Bis, Wojciech Bis: "Badania archeologiczne kościoła św. Katarzyny i cmentarza na warszawskim Służewie", Ad Rem: Kwartalnik akademicki. Warsaw: University of Warsaw, Międzywydziałowe Towarzystwo Naukowe Badań i Ochrony Swiatowego Dziedzictwa Kulturowego HUMANICA, 2012. ISSN 1899-0495. (in Polish)

- ^ a b c Ewa Korpysz: "Przemiany w architekturze kościoła św. Katarzyny na Służewie", Ad Rem: kwartalnik akademicki. Warsaw: University of Warsaw, Międzywydziałowe Towarzystwo Naukowe Badań i Ochrony Swiatowego Dziedzictwa Kulturowego HUMANICA, 2012. ISSN 1899-0495. (in Polish)

- ^ Marta Piber-Zbieranowska: Służew średniowieczny. Warsaw: Towarzystwo Naukowe Warszawskie, 2001, p. 232–233. ISBN 8390732858 (in Polish)

- ^ Tadeusz S. Jaroszewski: Księga pałaców Warszawy. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Interpress, 1985, p. 67. ISBN 83-223-2047-7. (in Polish)

- ^ Dobrosław Kobielski: Widoki dawnej Warszawy. Warsaw: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1984, p. 111. ISBN 9788303007025. (in Polish)

- ^ Sławek Kińczyk (8 March 2019). "Tarasy Pałacyku Krasińskich. Tego nie zobaczysz w realu! FOTO". haloursynow.pl (in Polish).

- ^ Barbara Petrozolin-Skowrońska (editor): Encyklopedia Warszawy, vol. 1. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 1994, p. 223. ISBN 83-01-08836-2. (in Polish).

- ^ a b "Wilanowski Park Kulturowy – tajemnica Gucin Gaju". um.warszawa.pl (in Polish). 7 December 2021.

- ^ Józef Kazimierski, Ryszard Kołodziejczyk, Żanna Kormanowa, Halina Rostowska: Dzieje Mokotowa. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1972, p. 51. (in Polish)

- ^ Lesław M. Bartelski: Mokotów 1944. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, 1986, p. 206–207. ISBN 83-11-07078-4. (in Polish)

- ^ Jubileusz 25-lecia posługi w parafii Św. Katarzyny ks. Józefa Romana Maja. Warsaw: Oficyna Wydawniczo-Poligraficzna Adam, 2010, p. 11. ISBN 978-83-7232-905-9. (in Polish)

- ^ Małgorzata Szejnert: Śród żywych duchów, Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak, 2012, ISBN 978-83-240-2212-0, OCLC 833924742. (in Polish)

- ^ a b Irena Grzesiuk-Olszewska: Warszawska rzeźba pomnikowa. Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Neriton, 2003, p. 178. ISBN 83-88973-59-2. (in Polish)

- ^ a b "Ursynalia". wyborcza.pl (in Polish). 16 November 2012.

- ^ "Ustawa z dnia 25 marca 1994 r. o ustroju miasta stołecznego Warszawy". isap.sejm.gov.pl (in Polish).

- ^ "Uchwała Nr 563 Rady Gminy Warszawa-Ursynów z dnia 18 czerwca 1998 r. z późniejszymi zmianami z dnia 18 czerwca 1998 r. w sprawie wprowadzenia Miejskiego Systemu Informacji w Gminie Warszawa-Ursynów" (PDF). zdm.waw.pl (in Polish).

- ^ "Uchwała Nr 366 Zarządu Gminy Warszawa-Ursynów z dnia 9 lutego 2000 r. w sprawie uzupełnienia i skorygowania Miejskiego Systemu Informacji w Gminie Warszawa-Ursynów" (PDF). zdm.waw.pl (in Polish).

- ^ "Ustawa z dnia 15 marca 2002 r. o ustroju miasta stołecznego Warszawy". isap.sejm.gov.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b "Rezerwat przyrody Skarpa Ursynowska". crfop.gdos.gov.pl (in Polish).

- ^ a b c "Wilanowski Park Kulturowy – rezerwat Skarpa Ursynowska". um.warszawa.pl (in Polish). 10 May 2021.

- ^ a b "Ósmy Park jest terenem prywatnym. Chcesz wejść? Musisz zapłacić. 'Decyzja została podyktowana kwestiami bezpieczeństwa'". warszawa.naszemiasto.pl (in Polish). 14 January 2020.