Singaporean Mandarin

| Singaporean Mandarin | |

|---|---|

| 新加坡华语 新加坡華語 Xīnjiāpō Huáyǔ | |

| Native to | Singapore |

| Region | Singapore |

Native speakers | 2.0 million (2016 census)[1] L2 speakers: 880,000 (no date)[1] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

| Simplified Chinese characters (official) Traditional Chinese characters (personal use, informal) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Promote Mandarin Council Singapore Centre for Chinese Language |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| ISO 639-6 | huyu (Huayu) |

| Glottolog | None |

| Linguasphere | or 79-AAA-bbd-(part)(=colloquial) 79-AAA-bbb(=standard) or 79-AAA-bbd-(part)(=colloquial) |

| IETF | cmn-SG |

| Singaporean Mandarin | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 新加坡华语 | ||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 新加坡華語 | ||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | Singapore Chinese Language | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

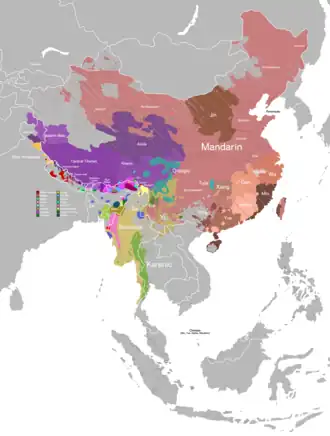

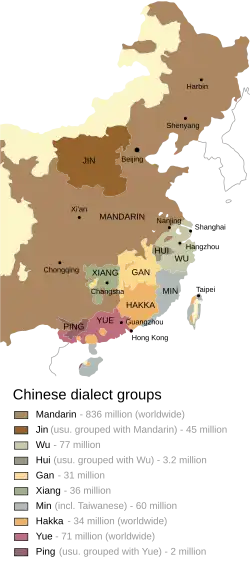

Singaporean Mandarin (simplified Chinese: 新加坡华语; traditional Chinese: 新加坡華語; pinyin: Xīnjiāpō Huáyǔ) is a variety of Mandarin Chinese spoken natively in Singapore. Mandarin is one of the four official languages[2] of Singapore alongside English, Malay and Tamil.

Singaporean Mandarin can be divided into two distinct forms: Standard Singaporean Mandarin and Colloquial Singaporean Mandarin (Singdarin). These forms are easily distinguishable to speakers proficient in Mandarin. The standard form is used in formal contexts, including television and radio broadcasts, and is the variant taught in government and international schools. The colloquial form is used informally among Singaporeans. Singaporean Mandarin contains many unique loanwords from other Chinese dialects, such as Hokkien, as well as Singapore's other official languages: English, Malay and Tamil.

The widespread adoption of Singaporean Mandarin by the Chinese community in Singapore followed the government's Speak Mandarin Campaign launched in 1979. Today, it is the second most commonly spoken language in Singapore after English and has largely replaced Singaporean Hokkien as the lingua franca among Singaporean Chinese.[3] The rise of China in the 21st century has increased the prominence of Mandarin proficiency in Singapore.[4] By 2010, more Singaporeans were multilingual, with a growing number speaking two or more languages.[5]

Since the early 21st century, the influx of mainland Chinese immigrants from mainland China[6] has influenced Singaporean Mandarin to align more closely with Standard Chinese, although distinctive features have been retained.[7] The language continues to evolve, drawing influence from Standard Chinese, Taiwanese Mandarin and English. Since the 2010s, the proportion of Singaporean Chinese speaking Mandarin at home has begun to decline, with Singaporean English increasingly used instead.

Overview

Standard Singaporean Mandarin

The official standard of Mandarin in Singapore, locally known as Huáyǔ (华语; 華語), is based on the phonology of the Beijing dialect and the grammar of Vernacular Chinese. It is largely identical to the standard Mandarin used in the People's Republic of China (known there as Pǔtōnghuà 普通话) and in Republic of China (Taiwan) (known there as Guóyǔ 國語 and more recently also as Huáyǔ 華語). Standard Singaporean Mandarin, typically heard in television and radio news broadcasts, is generally closer to Guoyu in terms of phonology, vocabulary and grammar than to Putonghua. Differences are minor and mainly appear in the lexicon.

Colloquial Singaporean Mandarin

Also commonly known as Singdarin (simplified Chinese: 新加坡式华语; traditional Chinese: 新加坡式華語; pinyin: Xīnjiāpōshì Huáyǔ; Wade–Giles: hsin1 chia1 p'o1 shih4 hua2 yü3[8]) or Singnese (Chinese: 星式中文; pinyin: Xīngshì Zhōngwén; Wade–Giles: hsing1 shih4 chung1 wen2; lit. 'Sing[apore] colloquial Chinese language'[9]), the colloquial variety is a Mandarin dialect native and unique to Singapore similar to its English-based counterpart Singlish. It is based on Mandarin but has a large amount of English and Malay in its vocabulary. There are also words from other Chinese languages such as Cantonese, Hokkien and Teochew as well as Tamil.[10] While Singdarin grammar is largely identical to Standard Mandarin, there are significant divergences and differences especially in its pronunciation and vocabulary.

In terms of colloquial spoken Mandarin, Singaporean Mandarin is subjected to influence from the local historical, cultural and social influences of Singapore. As such, there are remarkable differences between colloquial Singaporean Mandarin and Standard Chinese, and a non-Singaporean Chinese speaking individual may find it difficult to understand.[11]

Features of Singaporean Mandarin

Singaporean Mandarin has preserved the vocabulary and certain other features from Classical Chinese and early Vernacular Chinese (早期白話; zǎoqī báihuà), dating back from the early 20th century. Since Singapore's Chinese medium schools adopted Chinese teaching materials from Republic of China in the early 20th century, Singapore's early Mandarin pronunciations was based on the Zhuyin in the Dictionary of National Pronunciation (國音字典; Guó yīn zìdiǎn) and Vocabulary of National Pronunciation for Everyday Use (國音常用字彙; Guó yīn chángyòng zìhuì). As such, it had preserved many older forms of pronunciations. In addition, during its initial development, Singaporean Mandarin was also influenced by the other Chinese varieties of Singapore such as Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese etc.

From 1949 to 1979, due to lack of contact between Singapore and People's Republic of China, Putonghua did not exert any form of influence on Singaporean Mandarin. On the contrary, the majority of Mandarin Chinese entertainment media, Chinese literature, books and reading materials in Singapore came mainly from Taiwan. As a result, Singaporean Mandarin has been influenced by Taiwanese Mandarin to a certain degree. After the 1980s, along with China's Open Door Policy, there was increasing contact between Singapore and mainland China, thus increasing Putonghua's gradual influence on Singaporean Mandarin. These influences included the adoption of pinyin and the shift from usage of Traditional Chinese characters to Simplified Chinese characters. Much of the lexicon from Putonghua had also found its way into Singaporean Mandarin although not to a huge extent.

History

Background

Historical sources indicate that before 1819, when Stamford Raffles arrived in Singapore, there were already a few Chinese settlers on the island. After Raffles established Singapore as a trading post in 1819, many Peranakan from Malaya and European merchants began arriving. To meet the growing demand for labour, large numbers of coolies were brought from China.[13]

The influx of Chinese labourers increased after the Opium War. Those who migrated from China to Singapore during the 19th and early 20th centuries were known as "sinkeh" (新客). Many were contract labourers, including dockworkers. Most came to escape poverty and seek better opportunities, while others fled the wars and unrest in China during the first half of the 20th century. The majority originated from the southern provinces of Fujian, Guangdong and Hainan.[13]

These sinkeh included large numbers of Hoklo (Hokkien), Teochew, Cantonese and Hainanese. They brought with them a variety of Chinese languages, including Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka and Hainanese. As these languages were mutually unintelligible, clan associations were formed along lines of dialect and ancestral origin to provide social support for members of the same linguistic group.The use of Mandarin to serve as a lingua franca amongst the Chinese only began with the founding of Republic of China, which established Mandarin as the official tongue.[13]

Development of Mandarin in Singapore

Before the 20th century, old-style private Chinese schools in Singapore, known as sīshú (私塾), generally used Chinese dialects such as Hokkien, Teochew and Cantonese as the medium of instruction for teaching the Chinese classics and Classical Chinese.[14] Singapore's first Mandarin-medium classes appeared around 1898, but Chinese dialect schools remained in operation until 1909.[15] Following the May Fourth Movement in 1919 and the influence of the New Culture Movement in China, these schools gradually replaced dialect instruction with Mandarin Chinese, or Guóyǔ (國語). The Kuomintang (KMT)–led government of China supported this shift by sending teachers and textbooks, and by the 1920s all Chinese schools in Singapore had adopted Mandarin despite British discouragement.[16][17]

In the early years of Mandarin education in Singapore, there was no fully standardised colloquial form to serve as a learning model.[14] Most teachers were from southern China and spoke with strong regional accents, which influenced Singaporean Mandarin by eliminating features such as erhua (兒化) and the light tone (輕聲). The publication of the Dictionary of National Pronunciation in 1919 introduced a hybrid system combining northern sounds with southern rhymes, including the checked tone (入聲), but it was only in 1932 with the Vocabulary of National Pronunciation for Everyday Use, based entirely on the Beijing dialect, that a consistent standard emerged. This standard was adopted in Singapore’s Chinese schools. During the 1930s and 1940s, new immigrants from China, known as xīn kè (新客), helped establish more Chinese schools, further expanding Mandarin's use. Over time, the term for Mandarin in Singapore shifted from Guóyǔ (National Language) to Huáyǔ (Chinese Language).[14][17]

From the 1950s to the 1970s, Singaporean Mandarin was heavily influenced by Taiwanese Mandarin, as most Chinese publications came from Taiwan or Hong Kong.[14] In the 1980s, following mainland China's economic reforms, Singapore adopted Hanyu Pinyin and switched from Traditional Chinese characters to Simplified Chinese characters. The Speak Mandarin Campaign launched in 1979 spurred further standardisation, with the Promote Mandarin Council conducting research based on linguistic models from mainland China and Taiwan. Since the 1990s, greater interaction with mainland China and a large influx of Chinese migrants have brought more Putonghua vocabulary into Singaporean Mandarin.[17]

Differences from Standard Mandarin

Vocabulary

Major differences between Singaporean Mandarin Huayu (华语) and Putonghua lie in the vocabulary used. A lack of contact between Singapore and China from 1949 to 1979 meant that Singaporean Mandarin had to invent new words to fit the local context, as well as borrow words from Taiwanese Mandarin or other Chinese varieties that were spoken in Singapore. As a result, new Mandarin words proprietary to Singapore were invented.

The Dictionary of Contemporary Singaporean Mandarin Vocabulary (时代新加坡特有词语词典) edited by Wang Huidi (汪惠迪) listed 1,560 uniquely local Singaporean Mandarin words, which are not used in mainland China or Taiwan.[18]

Unique Singaporean Mandarin words

There are many new terms that are specific to living in Singapore. These words were either translated from Malay and Chinese dialects (or invented) as there were no equivalent words in Putonghua. Some of the words are taken from the Hokkien translation of Malay words. Words translated from Malay into Hokkien include kampung (甘榜, English 'village'), pasar (巴刹, English 'market'). This explains the uniquely Singapore Mandarin words.

| Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | Definition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 紅毛丹 | 红毛丹 | hóngmáodān | rambutan (a type of Southeast Asian fruit) |

| 奎籠 | 奎笼 | kuílóng | kelong (a place for fishing) |

| 甘榜 | 甘榜 | gānbǎng | kampung (village) |

| 沙爹 | 沙爹 | shādiē | Satay (a type of Singaporean Malay food) |

| 囉㘃/羅惹 | 罗惹 | luōrě | Rojak (a type of Singaporean Malay food) |

| 清湯 | 清汤 | qīngtāng | clear soup or broth |

| 固本 | 固本 | gùběn | coupon. Also used for car parking |

| 組屋 | 组屋 | zǔwū | flat built by Housing Development Board |

| 擁車證 | 拥车证 | yōngchēzhèng | car ownership-license |

| 保健儲蓄 | 保健储蓄 | bǎo jiàn chǔ xǜ | medisave (medical saving) |

| 週末用車 | 周末用车 | zhōu mò yòng chē | Weekend Car (a classification of car ownership in Singapore) |

| 財路 | 财路 | cáilù | "Giro" (a system of payment through direct bank account deduction in Singapore) |

| 巴刹 | 巴刹 | bāshā | "bazaar" or market or pasar (Malay) |

| 民衆俱樂部 / 聯絡所 |

民众俱乐部 / 联络所 |

mín zhòng jù lè bù lián luò suǒ |

community centre |

| 叻沙 | 叻沙 | lāsā | laksa (a type of curry noodle) |

| 垃圾蟲 | 垃圾虫 | lèsè chóng/lājī chóng | "litter-bug"; someone who violated the law for littering |

| 排屋 | 排屋 | páiwū | terrace house |

| 建國一代 | 建国一代 | jiàn guó yí dài | Pioneer generation; to describe the early builders of Singapore |

Same meaning, different words

There are some words used in Singaporean Mandarin that have the same meaning with other words used in Putonghua or Taiwanese Mandarin:

| Chinese Characters | Pinyin | Definition | Putonghua | Guoyu | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 乐龄 | lè líng | old people | 老龄 lǎo líng |

年長者 nián zhǎng zhě |

|

| 三文治 | sān wén zhì | sandwich | 三明治 sān míng zhì |

From English "sandwich" via Cantonese 三文治 sāam màhn jih | |

| 德士 | déshì | taxi | 出租车 chūzūchē |

計程車 jìchéngchē |

compare Cantonese 的士 dīk sih (from English "taxi"). |

| 货柜 | huò guì | container | 集装箱 jí zhuāng xiāng |

貨櫃 huò guì |

|

| 火患 | huǒ huàn | fire | 火災 huǒ zāi |

火警 huǒ jǐng |

火災 is also used in Singapore and Taiwan. |

| 耐 | nài | durable/lasting | 耐用 nài yòng |

耐用 nài yòng |

From classical Chinese. 耐用 is also used in Singapore. |

| 驾车 | jià chē | drive a car | 开车 kāi chē |

開車 kāi chē |

驾 originates from classical Chinese. 开车 is also used in Singapore. 驾车 has also found its way into Putonghua vocabulary. |

| 首个 | shǒu gè | first | 第一个 dì yī gè |

第一个 is also used in Singapore. 首个 has also found its way into Putonghua vocabulary. | |

| 公众 | gōng zhòng | public mass | 群众 qún zhòng |

群眾 qún zhòng |

公众 has also found its way into Putonghua vocabulary. 群众 is also used in Singapore, as in 群众大会 (rally). |

| 群体 | qún tǐ | organized group | 集体 jí tǐ |

集體 jí tǐ |

群体 has also found its way into Putonghua and Taiwanese Mandarin vocabulary. 集体 is also used in Singapore, more commonly as an adverb (en masse). |

| 第一时间 | dì yī shí jiān | immediately | 立刻 lì kè |

立即 lì jí |

Literally 'the first timing'. Both 立刻 and 立即 are used in Singapore as well. |

| 一头雾水 | yī tóu wù shǔi | blurred and confused | 晕头转向 yūn tóu zhǔan xìang |

糊裡糊塗 hú lǐ hú tú |

The idiom 一头雾水 has also found its way into Putonghua vocabulary. |

| 码头 | mǎ tóu | dock | 港口 gǎng kǒu |

港口 gǎng kǒu |

From Hokkien/Cantonese, Hokkien: bé-thâu, Cantonese: ma tau. 头 may carry a neutral tone in Mandarin, thus the phrase becoming mǎtou. |

| 领袖 | lǐng xiù | leader | 领导 lǐng dǎo |

領袖 lǐng xiù |

領袖 is sometimes used in Singapore, more commonly as a verb (to lead). |

| 手提电话 | shǒu tí diàn huà | mobile phone | 手机 shǒu jī |

行動電話/手機 xíng dòng diàn huà/shǒu jī |

手机 is also used in Singaporean Mandarin, although less frequently. |

| 客工 | kè gōng | foreign worker | 外勞 wài láo |

外劳 also appears in some Singaporean Chinese writing (e.g. Lianhe Zaobao) | |

| 农夫 | nóng fū | farmer | 农民 nóng mín |

鄉民 xiāng mín |

农夫 was an older Chinese term used in China before 1949, but continues to be used in Singapore. |

| 巴士 | bā shì | bus | 公交车 gōng jiāo chē |

公車/巴士 gōng chē/bā shì |

From Cantonese. |

| 电单车 | diàn dān chē | motorcycle | 摩托车 mó tuō chē |

機車 jī chē |

From Cantonese. |

| 罗里 | luó lǐ | lorry | 卡车 kǎ chē |

貨車 huò chē |

From English word "lorry". |

| 角头 | jiǎo tóu | corner | 角落 jiǎo luò |

角落 jiǎo luò |

From Hokkien kak-thâu. Note that in Putonghua, 角头 actually means "chieftain of mafia/secret society" instead of "corner". Occasionally, the phrase carries the Putonghua meaning in Singaporean context, so the latter may be clarified with a postposition like 间 jiān (in between), 内 nèi or 里 lǐ (both mean 'in(side)'). |

| 散钱 | sǎn qián | small change | 零钱 líng qián |

零錢 líng qián |

Originates from classical Chinese. 散钱 is also used in Putonghua, while 零钱 is sometimes used in Singapore, especially in writing. |

Same word, different meanings

There are certain similar words used in both Singaporean Mandarin and Putonghua, but have different meanings and usage.

| Chinese Characters | Pinyin | Meaning in Huayu | Meaning in Putonghua | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 小姐 | xiǎo jiě | Miss | Prostitute or lady involved in sex trade | 小姐 is used to refer to a lady or waitress in restaurant in Singaporean Mandarin. However, in Putonghua, 小姐 has negative connotation in the northern provinces, used mainly to refer to prostitutes. 女士 or 服务员 tends to be more commonly used in Putonghua, instead of 小姐. In Taiwan it is used the same way as in Singapore. |

| 对付 | duì fù | fight against/counteract | take action to deal with a person or problem | 对付 is used to refer in negative connotation in Singaporean Mandarin to mean fight or counteract e.g. against a criminal or terrorist. But in Putonghua, it can have positive connotation to mean take action dealing with a person or problem. |

| 懂 | dǒng | know | understand | 懂 is commonly used in Singaporean Mandarin to mean "know" instead of 知道 (Putonghua). 懂 means 'understand' in Putonghua. |

| 计算机 | jì suàn jī | calculator | computer | 计算机 in Putonghua means 'computer', and 计算器 is used instead to refer to 'calculator'. In recent years, 电脑 for computer has become more popular in Putonghua. |

Loanwords and influence from other Sinitic languages

There is quite a number of specific words used in Singaporean Mandarin that originate from other Chinese varieties such as Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese etc. These languages have also influenced the pronunciation in Singaporean Mandarin.

| Chinese Characters | Pinyin | Definition | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 阿兵哥 | ā bīng gē | soldiers | originates from Hokkien "a-peng-ko" |

| 怕输 | pà shū | afraid to lose | originates from Hokkien "kiaⁿ-su" (惊输) |

| 几时 | jǐ shí | when? | originates from Hokkien "kuí-sî" or Classical Chinese |

| 阿公 | ā gōng | grandpa | originates from Hokkien "a-kong" |

| 阿妈 | ā mā | grandma | originates from Hokkien "a-má" (阿嬤). |

| 阿婆 | ā pó | old lady | originates from Hokkien "a-pô" |

| 很显 | hěn xiǎn | very boring | spoken colloquially in Singaporean Mandarin instead of 无聊/闷 (in Standard Mandarin). The word "显" originates from Hokkien 'hián-sèng' (显圣). |

| 敢敢 | gǎn gǎn | be brave/daring | spoken colloquially in Singaporean Mandarin instead of 勇敢 (in Standard Mandarin). For instance, 敢敢做介开心人 (dared to be a happy person – also the title for a Mediacorp Channel 8 sitcom). The word "敢敢" originates from Hokkien "káⁿ-káⁿ" (daring) |

| 古早 | gǔ zǎo | ancient | originates from Hokkien "kó͘-chá". Appears in some Singaporean Chinese writing (e.g. Hawker Centre) instead of 古時候 (in Standard Mandarin). |

| 做工 | zuò gōng | work | originates from Hokkien "cho-kang", which means 'work'. 做工 is often spoken colloquially in Singaporean Mandarin instead of 工作/上班 (in Standard Mandarin). In Standard Mandarin, 做工 usually means doing work that involves manual hard labour. |

| 烧 | shāo | hot | originates from Hokkien "sio", which means 'hot'. 烧 is often spoken colloquially in Singaporean Mandarin instead of 热/烫 (in Standard Mandarin). |

| 什么来的 | shén me lái de | What is this? | originates from Hokkien "siáⁿ-mi̍h lâi ê" (啥物來的). 什么来的 is often spoken colloquially in Singaporean Mandarin instead of the more formal 这是什么 (in Standard Mandarin) |

| 起价 | qǐ jià | price increase | originates from Hokkien "khí-kè". 起价 is often spoken colloquially in Singaporean Mandarin instead of the more formal 涨价 (in Standard Mandarin) |

| 做莫 | zuò mò | Why? / Doing what? | originates from Cantonese 做咩 zou me. 做莫 (or 做么) is often spoken colloquially in Singaporean Mandarin instead of the more formal 为什么/做什么 (in Standard Mandarin) |

| 哇佬 | wà láo | man! | Corruption of a vulgar Hokkien word |

| 是乜 | shì miē | is it? | The word 乜 mēh, more often rendered as 咩 (see above), originates from Cantonese and is used in colloquial Singaporean Mandarin. Compare Standard Mandarin 是吗 shì ma. |

| 大耳窿 | dà ěr lóng | loan shark | originates from Cantonese. (compare Guoyu: 地下錢莊) |

| 搭客 | dā kè | passenger | originates from Cantonese. (compare Putonghua: 乘客) |

| 摆乌龙 | bǎi wū lóng | misunderstanding/make mistakes/confusion | originates from Cantonese. |

| 好脸 | hào liàn | boastful, likes to show off | originates from Teochew "ho lien" (好脸). Other than "likes to show off", the term can also describes someone who has a strong pride, i.e. cares about not losing face. (compare Putonghua: 爱出风头, Guoyu: 愛現) |

| 粿条 | guǒ tiáo | a type of flat noodle | originates from Teochew "kuey tiao" (粿条). Compare Cantonese "hor fan" (河粉) |

Loanwords and English influences

There is quite a number of specific words used in Singaporean Mandarin that originate or are transliterated from English. These words appear in written Singaporean Mandarin.

| Chinese Characters | Pinyin | Definition | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 摩多西卡 | móduōxīkǎ | motorcycle | Both 电单车 and 摩托车 are now more frequently used in Singaporean Mandarin |

| 巴仙 | bāxiān | percentage | 百分比 is standard |

Grammar

In terms of standard written Mandarin in Singapore, the Singaporean Mandarin grammar is almost similar to that of Putonghua. However, the grammar of colloquial Singaporean Mandarin can differ from that of Putonghua as a result of influence from other varieties of Chinese, classical Chinese and English. Some of the local Singaporean Mandarin writings do exhibit certain local Singaporean features.

Time

When speaking of minutes, colloquial Singaporean Mandarin typically uses the word 字 (zì), which represents a unit of 5 minutes. When referring to a number of hours (duration), 钟头 (zhōngtóu) is used instead of 小时 (xiǎoshí). For instance:

- 5 minutes: 一个字 (yī gè zì)

- 10 minutes: 两个字 (liǎng gè zì)

- 15 minutes: 三个字 (sān gè zì)

- 45 minutes: 九个字 (jiǔ gè zì)

- 1 hour: 一个钟头 (yī gè zhōng tóu)

The use of zì (字) originates from Hokkien (jī or lī), Cantonese or Classical Chinese. Its origin came from the ancient Chinese units of measuring time. In ancient Chinese time measurement, hours were measured in terms of shíchén (时辰), equivalent to 2 hours while minutes were measured in terms of kè (刻), equivalent to 15 minutes. Each kè was in turn divided into 3 zì (equivalent to 5 minutes). For instance, 7:45 pm is:

- 七 点 九 个 字 or 七 点 九。 (Singaporean Mandarin)

- 七 点 四十 五 分。 (Standard Mandarin)

Days of the week

As a result of Hokkien influence, colloquial Singaporean Mandarin typically uses the word "拜-" (bài) to refer to the days of the week, in lieu of Standard Mandarin "星期-" (xīngqí-). For instance:

- Monday: 拜一 (bàiyī) instead of 星期一 (xīngqíyī)

- Sunday: 礼拜天 (lǐbàitiān) or simply 礼拜 (lǐbài) instead of 星期日 (xīngqírì)

- A week: 一个礼拜 (yī gè lǐbài) instead of the more formal 一个星期 (yī gè xīngqí)

Both 拜 (bài) and 礼拜 (lǐbài) originate from Hokkien pài and lé-pài respectively.

Large numbers

In colloquial Singaporean Mandarin, 万 (wàn), referring to a "ten thousand" is often used, but 十千 (shí qiān), referring to "ten thousands" is occasionally used too. This usage was influenced by English numbering system and also Chinese Indonesian who frequently uses large Indonesian currency, Rp10000 (0.71 USD) and above.

Use of the word "先"

The word "先" (xiān) is often used at the end of a sentence in colloquial Singaporean Mandarin (instead of after a subject, as in Standard Mandarin), as a result of influence from Cantonese grammar. For example, take the sentence "You walk first":

- 你 走 先。 (Singaporean Mandarin)

- 你 先 走。 (Standard Mandarin)

- 你 走 先。 (Cantonese)

- (Note that the reverse, 你先走 is ungrammatical in spoken Cantonese.)

The use of the word "而已"

而已 (éryǐ) is more common in colloquial Singaporean Mandarin than in Standard Mandarin, which uses 罢了 (bàle). While 而已 (éryǐ) is also used in colloquial Mandarin within Mainland China, but perhaps to a lesser extent as compared to Singapore or Taiwan. For example:

Translation: only like this / only this kind!

- 这 样子 而已 啊! (Singaporean Mandarin)

- 这 样子 罢了! (Standard Mandarin)

- 這 樣子 算了 吧! (Taiwanese Mandarin)

"大只" and "小只"

When people describe the size of animals, for example, chicken, these are used to mean 'large' and 'small'. Putonghua tends to use 肥 and 瘦 instead. These two words are also used to refer to the body frame of a person. "大只" refers to people who appear to be tall, masculine or with a large body build. "小只" is used to describe people with a small built, tiny frame.

Use of the word "啊" as an affirmative

In colloquial Singaporean Mandarin, the word "啊" is often used in response to a sentence as an affirmative. It is often pronounced as /ã/ (with a nasal tone) instead of 'ah' or 'a' (in Putonghua). Putonghua tends to use "是(的)/对啊/对呀" (shì (de)/duì a/duì ya), "哦" (ó), "噢" (ō), "嗯" (en/ng) to mean "yes, it is".

Use of the word "才" instead of "再"

In Singaporean Mandarin, there is a greater tendency to use the word cái "才" (then) in lieu of Standard Mandarin zài "再" (then), which indicates a future action after the completion of a prior action. For instance:

- "关税申报单刚巧用完了,打算在飞机上领了才填写。"

- The tax declaration forms have all been used up, I'll have to get a form on the plane then and fill it out.

- "现在不要说,等他吃饱了才说。"

- Don't say anything now; say it only after he has finished his meal.

The use of the word "有"

In Singaporean Mandarin, one typical way of turning certain nouns into adjectives, such as 兴趣 (xìngqù, 'interest'), 营养 (yíngyǎng, 'nutrition'), 礼貌 (lǐmào, 'politeness'), is to prefix the word "有" (yǒu) at the front of these nouns.

For example:

- "很有兴趣" (hěn yǒu xìngqù – very interested)

- "很有营养" (hěn yǒu yíngyǎng – very nutritious)

- "很有礼貌" (hěn yǒu lǐmào – very polite).

有 is sometimes omitted in writing.

Reduplication of verbs preceding "一下"

In Singaporean Mandarin, verbs preceding "一下" may be reduplicated, unlike in Putonghua. This practice is borrowed from the Malay and Indonesian method of pluralizing words. In Putonghua grammar, the use of the word "一下(儿)" (yīxià(r)) is often put at the back of a verb to indicate that the action (as indicated by the verb) is momentary.

For example:

- 想 想 一下 。(Singaporean Mandarin)

- 想 一下 。(Standard Mandarin)

- Think for a while.

- 研究 研究 一下 。 (Singaporean Mandarin)

- 研究 一下 。(Standard Mandarin)

- Research for a while.

Colloquial use of the word "被"

Singaporean Colloquial Mandarin tends to use 被 (bèi) more often than Putonghua, due to influence from English and/or Malay. It is used to express a passive verb.

Compare the following:

- "The road has been repaired"

- 马路 被 修好 了 (Singaporean Mandarin)

- 马路 已 修好 了 (Putonghua)

Using adjectives as verbs

Sometimes, colloquial Singaporean Mandarin might use intransitive verbs as transitive.

For instance, 进步 (improve) is an intransitive verb. But as influenced by the use of English, "I want to improve my Chinese" is sometimes said in Singaporean Mandarin as "我要进步我的华语". In Standard Mandarin, this is "我要让我的华语进步".

Phonology and tones

The phonology and tones of Singaporean Mandarin are generally similar to that of Standard Mandarin. There are 4 tones similar to those in Standard Mandarin, but Erhua (儿化, -er finals) and the neutral tone (轻声, lit. 'light tone') are generally absent in Singaporean Mandarin.

The earliest development of Singaporean Mandarin includes the old Beijing phonology (老国音), followed by new Beijing phonology (新国音) and then finally Hanyu Pinyin of mainland China. In its initial development, Singaporean Mandarin was highly influenced by the ru sheng (入声, checked tone or 5th tone) from other Chinese varieties. As such, the 5th tone did appear in earlier Singaporean Mandarin.[19] The characteristics of the 5th tone are as follows:

- It is a falling tone. The common tone letter is 51, but sometimes it is 53.

- The tone does not last long. It feels more like an 'interrupted stop'.

- The syllable which carries the tone had a glottal stop; sometimes the final sounds to be clear, but sometimes, it does not sound very clear. This glottal stop not only interrupts the lasting period of the tone, but also makes the start of consonant stronger, thus nearing itself more to a voiced consonant.

However, due to years of Putonghua influence, prevalence of the 5th tone in Singaporean Mandarin is declining.[20]

Minor differences occur between the phonology (tones) of Standard Singaporean Mandarin and other forms of Standard Mandarin.

| Chinese character | Definition | Singapore | Mainland China | Taiwan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 休息 | Take a rest | xiūxí | xiūxi | xiūxí | The character 息 is pronounced with the 2nd tone in Standard Singaporean Mandarin, same as that in Taiwan. In mainland China, 息 is pronounced with a neutral tone instead. |

| 垃圾 | Rubbish | lèsè/lājī | lājī | lèsè | The pronunciation for 垃圾, which was influenced by Wu Chinese, is the same in Singapore and Taiwan where the pronunciation from before 1949 is maintained. However, due to influence from mainland China, the pronunciation is inclining itself towards Standard Chinese. |

| 角色 | Role | jiǎosè | juésè | jiǎosè/juésè | The pronunciation for 角色 is the same in Singapore and Taiwan where the pronunciation jiǎosè from before 1949 has been maintained. However, both juésè and jiǎosè can be used interchangeably in the Chinese-speaking world. |

| 包括 | Include | bāokuò | bāokuò | bāoguā/bāokuò | The pronunciation for 包括 is the same in Singapore and mainland China. |

| 血液 | Blood | xuěyì | xuèyè/xuěyè | xiěyì/xiěyè | Singapore and Taiwan uses the literary pronunciation of both characters xuěyì from before 1949. |

Influences from other languages in Singapore

Just like any languages in Singapore, Singaporean Mandarin is subjected to influences from other languages spoken in Singapore.

Singaporean Hokkien is the largest non-Mandarin Chinese variety spoken in Singapore. The natural tendency of Hokkien-speakers to use the Hokkien way to speak Mandarin has influenced to a large degree the colloquial Mandarin spoken in Singapore. The colloquial Hokkien-style Singaporean Mandarin is commonly heard in Singapore, and can differ from Putonghua in terms of vocabulary, phonology and grammar.

Besides Singaporean Hokkien, Mandarin is also subjected to influence coming from other Chinese dialects such as Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, and Hainanese, as well as English and Malay.

Writing system

In Singapore, simplified Chinese characters are the official standard used in all official publications as well as the government-controlled press. While simplified Chinese characters are taught exclusively in schools, the government does not officially discourage the use of Traditional characters. Therefore, many shop signs continue to use Traditional characters.

As there is no restriction on the use of traditional characters in the mass media, television programmes, books, magazines and music CDs that have been imported from Hong Kong or Taiwan are widely available, and these almost always use Traditional characters. Most karaoke discs, being imported from Hong Kong or Taiwan, have song lyrics in Traditional characters as well. While all official publications are in simplified characters, the government still allows parents to choose whether to have their child's Chinese name registered in Simplified or Traditional characters though most choose the former.

Singapore had undergone three successive rounds of character simplification, eventually arriving at the same set of Simplified characters as the People's Republic of China. Before 1969, Singapore generally used Traditional characters. From 1969 to 1976, the Ministry of education launched its own version of Simplified characters, which differed from that of mainland China. But after 1976, Singapore fully adopted the Simplified characters of mainland China.

Chinese writing style and literature

Chinese writing style

.jpg)

Before the May Fourth Movement in 1919, Singapore Chinese writings were based on Classical Chinese. After the May Fourth Movement, under the influence from the New Culture Movement in China, the Chinese schools in Singapore began to follow the new education reform as advocated by China's reformist and changed the writing style to Vernacular Chinese.

Singapore's Chinese newspaper had witnessed this change from Vernacular Chinese. Lat Pau, one of the earliest Chinese newspaper, was still using Classical Chinese in 1890. By 1917, it continued to use Classical Chinese. But by 1925, it had changed to Vernacular Chinese. After this, all Chinese newspaper in Singapore used Vernacular Chinese.

Singaporean Chinese Literature

The development of the Singaporean Chinese literature reflected the history of immigrants in Singapore. When many Chinese writers from Southern China arrived in Singapore, they established Chinese schools, newspaper press etc. They contributed a lot to the development of Chinese literature in Singapore. In 1919, the New National Magazine (新國民雜誌) marked the birth of Singaporean Chinese literature. In those days, the migrant's mindset was still deeply entrenched. Many of the literary works were influenced by New Culture Movement. Most of the literary works that were published originated from the works of writers in China.

In 1925, the presence of literary supplements such as Southern Wind (南風), Light of Singapore (星光) brought a new dimension to Singaporean Chinese literature. They differed from past magazine that relied on writers from China. It was at this time, that the thoughts of Nanyang began to surface the corner. In January 1927, the Deserted Island (荒島) published in the New National Press (新國民日報) clearly reflected the features of Nanyang in its literary work. The "localization" literary works mostly described the lifestyle in Nanyang, the people and their feelings in Nayang. The quality of Singaporean Chinese literature had greatly improved.

In 1937, the outbreak of Second Sino-Japanese War raised the anti-Japanese sentiment. The literature during these times reflected the missions of national salvation against the Japanese. This brought a halt to the localization movement and in turn re-enacted a sense of Chinese nationalism amongst the migrants in Singapore. From 1941 till 1945, during the Japanese occupation of Singapore, the activities for Chinese literature was halted.

After the war, people in Singapore began to have a sense of belonging to this piece of land, and they also had a desire for freedom and democracy. During this times, Singaporean Chinese literature was inclined towards Anti-colonialism. With new arts and thoughts, between 1947 – 1948, there was a debate between "Unique Singaporean Literary Art" and "literary thoughts of migrants". The results from these debated led to a conclusion that the Singaporean Chinese literature was going to develop on its own independently. The "localization" clearly marked the mature development of Singaporean Chinese literature.

During the 1950s, writers from Singapore drew their literary works mostly from the local lifestyle and events that reflected the lifestyle from all areas of the society. They also included many Chinese-dialect proverbs in their works. They created unique works of literature. Writers including Miao Xiu (苗秀), Yao Zhi (姚紫), Zhao Rong (趙戎), Shu Shu (絮絮) etc. represented the writers of "localization" works.

From 1960 to 1970, the number of literary works published began to increase. Locally-born and locally bred Singaporean writers became the new writers in the stage of Singaporean Chinese literature. Their works were mainly based on the views of Singaporeans towards issues or context happening in Singapore. They continued the "localization" movement and brought the Singaporean Chinese literature to a new dimension.

Arts and entertainment

Music

A Mandopop scene began to emerge in Singapore in the 1960s,[21] while the Speak Mandarin Campaign intensified the presence of Mandopop on local radio and television.[22] The 1980s saw the development of xinyao—a genre of contemporary Mandarin ballads with themes such as romance and life in Singapore, and popularized by singer-songwriters such as Liang Wern Fook.[23][24]

Opera

Films

Sociolinguistics

Politics

Language plays an important role in Singapore politics. Up to today, it is still important for politicians in Singapore to be able to speak their mother tongue (and even other dialects) fluently in order to reach out to the multilingual community in Singapore.

According to observation, an election candidate who is able to speak fluent Mandarin has a higher chance of winning an election. As such, most election candidates will try to use Mandarin in campaign speeches in order to attract Mandarin-speaking voters.[25]

Singaporean Mandarin Standard

Some Chinese elites in Singapore had criticized that the Mandarin standard of Chinese Singaporean has dropped greatly due to the closure or subsequent conversion of Chinese-medium schools to English-medium schools in the 1980s. Others attributed the drop in standard to the lack of learning Chinese literature in schools.

Ever since 1965 when Singapore became independent, bilingual policy has become the pillar of Singapore's education. The first language of Singapore was English, while Mandarin was chosen as the "mother tongue" of Chinese Singaporean. Generally, most Chinese Singaporean can speak Mandarin fluently, but are usually weaker in writing Chinese.[26]

Influence of Mainland China's economic rise on Singapore

In recent years, with the subsequent economic rise of mainland China and a transition from a world factory to a world market, Mandarin has become the 2nd most influential language after English. Besides transmitting Chinese culture values, many people began to realize the economic values of Mandarin, which has raised the interests of local and working professionals in learning Mandarin.[27]

Language policy and culture

Under the bilingual policy of Singapore, Chinese Singaporeans had a greater chance to speak and use English especially in school and at work. But this can cause a relative limitation in the use of mother tongue. Generally speaking, most Chinese Singaporeans are able to speak Mandarin, and also read newspapers in it, but only a minority is able to use it at a professional level such as academic research, literary writing etc. In the endeavor to use English, some Chinese Singaporeans even distanced themselves from the mother tongue culture, resulting in the erosion of Chinese culture in Singapore.[28]

Media

Since the establishment of the Speak Mandarin Campaign in 1979, all Chinese-language programming broadcast by Singapore state media outlets, particularly the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation (SBC) and its successors, have been in Mandarin.[29] Its current incarnation Mediacorp runs two Mandarin-language television channels, Channel 8 and Channel U, as well as the radio stations Yes 933 (contemporary pop), Capital 958 (classic hits), and Love 972 (adult contemporary). SPH Media and So Drama! Entertainment also run Mandarin radio stations, while SPH owns the country's only Mandarin-language daily newspaper, the Lianhe Zaobao.

See also

- Singapore Chinese characters

- Speak Mandarin Campaign

- Chinese Singaporean

- Languages of Singapore

- Malaysian Mandarin

- Comparison of national standards of Chinese

- Standard Mandarin

References

Notes

- ^ a b Mandarin Chinese (Singapore) at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ^ "Republic of Singapore Independence Act 1965 - Singapore Statutes Online". sso.agc.gov.sg. Retrieved 20 July 2024.

- ^ Leong Koon Chan. "Envisioning Chinese Identity and Multiracialism in Singapore". Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ "RPT-FEATURE-Eyeing China, Singapore sees Mandarin as its future". Reuters. 16 September 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2011.

- ^ SINGAPORE DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS. "CENSUS OF POPULATION 2010 STATISTICAL RELEASE 1 ON DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS, EDUCATION, LANGUAGE AND RELIGION" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 January 2011. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ 中国新闻网 (China News Site). "探讨新加坡人与中国新移民:接纳与融入间的对视 (An insight into Singaporean and New Chinese immigrants: receiving and assimilation)" (in Chinese). Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ 中国新闻网(China News Site). "新加坡内阁资政:新加坡华语尽量向普通话靠拢 (Lee Kuan Yew: Singaporean Mandarin should incline itself towards Putonghua)" (in Chinese). Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ^ "中文·外来语来聚"掺"". 《三联生活周刊》. Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- ^ 顧長永 (Gu Changyong) (25 July 2006). 《新加坡: 蛻變的四十年》 (Singapore: The Changing Forty Years). Taiwan: 五南圖書出版股份有限公司. p. 54. ISBN 978-957-11-4398-9.

- ^ "重视新加坡本土华语的文化意义 (Attending to the cultural significance of Colloquial Singaporean Mandarin)". 華語橋 (Huayuqiao). Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ^ Cavallaro, Francesco; Seilhamer, Mark Fifer; Yen Yee, Ho; Bee Chin, Ng (10 August 2018). "Attitudes to Mandarin Chinese varieties in Singapore". Journal of Asian Pacific Communication. 28 (2): 195–225. doi:10.1075/japc.00010.cav. hdl:10356/137340. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Bukit Brown: Our Roots, Our Heritage

- ^ a b c James F. Warren. Rickshaw Coolie: A People's History of Singapore, 1880–1940. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-266-7. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d Lee Ching Seng (2 April 2024). "Overview of textbooks of Chinese-medium schools in Singapore (1819–1979)". singaporeccc.org.sg. Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ 洪鎌德◎台大國發所教授 (Hon Liande). "新加坡的語言政策 (Singapore's language policy)" (in Chinese). National Taiwan University. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ^ Henning Klöter, Mårten Söderblom Saarela (2020). Language Diversity in the Sinophone World: Historical Trajectories, Language Planning, and Multilingual Practices. Routledge. p. 211. ISBN 9781003049890.

- ^ a b c Lim, Guan Hock (June 2019). "Development of Chinese Education in Singapore (1819–1979)". A General History of the Chinese in Singapore. World Scientific: 419–444. doi:10.1142/9789813277649_0020. Retrieved 14 August 2025.

- ^ 时代新加坡特有词语词典 (Dictionary of Contemporary Singaporean Mandarin Vocabulary) (in Chinese). 新加坡联邦出版社出版. 1999.

- ^ Chen, Chung-Yu (January 1983). "A Fifth Tone in the Mandarin spoken in Singapore". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 11 (1). Chinese University Press: 92–119. JSTOR 23757822.

- ^ Lee, Leslie (2010). "The Tonal System of Singapore Mandarin" (PDF). In Lauren Eby Clemens and Chi-Ming Louis Liu (ed.). Proceedings of the 22nd North American Conference on Chinese Linguistics and the 18th International Conference on Chinese Linguistics. Vol. 1. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University. pp. 345–362.

- ^ Craig A. Lockard (1998). Dance of Life: Popular Music and Politics in Southeast Asia. University of Hawai'i Press. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-0824819187.

- ^ Welch, Anthony R. Freebody, Peter. Knowledge, Culture and Power. Routledge Publishing. ISBN 1-85000-833-7

- ^ Lee Tong Soon (2008). "Singapore". In Terry Miller; Sean Williams (eds.). The Garland Handbook of Southeast Asian Music. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415960755.

- ^ "新谣人张家强 半天谱出经典代表作". Lianhe Zaobao (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 22 December 2014.

- ^ 吴元华 Wu Yuanhua. "论新加坡华语文的"政治价值"(About the political values of Mandarin)" (in Chinese). Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ 吳英成 (Wu Yincheng). "新加坡雙語教育政策的沿革與新機遇 (Singapore's bilingual education and new opportunity)" (PDF) (in Chinese). Nanyang Technological University Institute of Education. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ 吳英成 (Wu Yingchen). "新加坡雙語教育政策的沿革與新機遇 (Singapore's Bilingual Policy and Opportunities)" (PDF) (in Chinese). Nanyang Technology University Institute of Education. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- ^ 陳學怡(Chen Xue Yi). "語言政策與幼兒教育 (Language Policy and Children's Education)" (PDF) (in Chinese). National Taichung Institute of Education Research center for kids education. Retrieved 2 September 2013.

- ^ Welch, Anthony R. Freebody, Peter. (1993). Knowledge, Culture and Power. Routledge Publishing. ISBN 1-85000-833-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Chinese books

- 周清海编著, 《新加坡华语词汇与语法》,新加坡玲子传媒私人有限公司出版,, September 2002, ISBN 981412723X, ISBN 978-981-4127-23-3 (Zhou, Qinghai (2002), Vocabulary and Grammar of Singaporean Mandarin, Lingzi Media)

- 周清海(著),《变动中的语言》,新加坡玲子传媒私人有限公司出版, 2009, ISBN 9814243922、ISBN 9789814243926 (Zhou, Qinghai (2009), The changing languages, Lingzi Media)

Bibliography in Chinese

- Differences between Huayu and Putonghua (新加坡华语和普通话的差异)

- Teacher from China feels that Singaporean Mandarin is very lively (中国老师觉得新加坡华语有活力)

- Comparison of Vocabulary used in Huayu and Putonghua (华语、普通话词汇比较)

- Influence of Singaporean Mandarin on PRC Mandarin (论新加坡华语对大陆汉语的影响----评"一直以来"的谬误)

- An Overview over the Changes of Singaporean Mandarin (新加坡华语变异概说).