Scandal (1950 film)

| Scandal | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Written by | Akira Kurosawa Ryūzō Kikushima |

| Produced by | Takashi Koide |

| Starring | Toshirō Mifune Takashi Shimura Yoshiko Yamaguchi Noriko Sengoku |

| Music by | Fumio Hayasaka |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Shochiku Co. Ltd. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 104 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Scandal (Japanese: 醜聞, Hepburn: Sukyandaru; or Shūbun)[a] is a 1950 Japanese film written and directed by Akira Kurosawa. The film stars Toshiro Mifune, Takashi Shimura and Yoshiko Yamaguchi.

Plot

Ichiro Aoye, an artist, meets a famous young classical singer, Miyako Saijo while he is working on a painting in the mountains. She is on foot, having missed her bus, but they discover they are staying at the same hotel so Aoye gives her a ride back to town on his motorcycle. On the way, they are spotted by paparazzi from the tabloid magazine Amour. Saijo refuses to grant the photographers an interview, so they plot their revenge and are able to take a picture of Aoye and Saijo on the balcony of her room and print it along with a fabricated story under the headline "The Love Story of Miyako Saijo".

Aoye is outraged by this false scandal and plans to sue the magazine. During the subsequent media circus, he is approached by a down-and-out lawyer, Hiruta, whose name means 'leechfield' (蛭田) and who claims to share Aoye's anger with the press. Aoye hires Hiruta as his attorney, but Hiruta is desperate for money to care for his daughter, Masako, who has a terminal case of tuberculosis, so he accepts a bribe from the editor of Amour in exchange for agreeing to throw the trial. The trial proceeds badly for the plaintiffs and Hiruta, struck by the kindness of Aoye and Saijo towards Masako and Masako's disgust at the way he is handling the case, becomes ridden with guilt. Masako dies near the end of the trial, convinced that Aoye and Saijo will win, since they have the truth on their side. On the final day in court Hiruta, prodded by his conscience, confesses to taking the bribe and Amour loses the case.

Cast

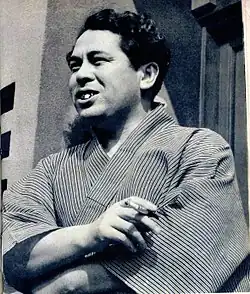

- Toshiro Mifune as Ichirō Aoye

- Takashi Shimura as Attorney Hiruta

- Yoshiko Yamaguchi as Miyako Saijo

- Noriko Sengoku as Sumie

- Yōko Katsuragi as Masako Hiruta

- Eitaro Ozawa as Hori

- Shinichi Himori as Editor Asai

- Ichiro Shimizu as Arai

- Fumiko Okamura as Miyako's mother

- Masao Shimizu as Judge

- Kokuten Kōdō as Old Man

- Bokuzen Hidari as Drunk

- Kōji Mitsui as Photographer

Production

In the aftermath of the Toho strikes and subsequent Red Purge of left-wing Japanese filmmakers from major studios, Kurosawa joined other filmmakers to form the independent production company Society of Film Artists to assist in the creation of his films.[2] Scandal was consciously conceived by Kurosawa as a protest film about the increasing popularity of tabloid journalism in Japan. Kurosawa, who generally did not engage with the press, had himself been the subject of rumours among magazines that had implied an unrequited romance between himself and the actress Hideko Takamine, whom Kurosawa had worked with on the film Horse (1941). The end of the occupation of Japan was approaching, and Kurosawa saw the rise in such journalism to be a social issue.[3]

Scandal, produced by Shochiku, was co-written by Kurosawa and Ryūzō Kikushima.[4][5] Kurosawa described some difficulty during the writing of the screenplay, with neither himself not Kikushima feeling satisfied with its development.[6] As he continued to write, Kurosawa found himself more interested by the character of Hiruta, and eventually wrote the film focussed around his character's internal conflict. About a year and a half after the film's release, he remembered that he had unconsciously based the character on a man he met at a bar once who spoke glowingly of his bedridden daughter while listing many faults with himself.[7]

Toshiro Mifune and Yoshiko Yamaguchi co-starred in the first of five collaborations together.[8] Yamaguchi later reflected on the experience as having been a frightening one, describing the atmosphere of the set as "incredibly intense", and Kurosawa as kind but a perfectionist.[9] The shooting of Scandal started in late 1949 and finished in January 1950, occurring concurrently with Mifune's wedding, and the realisation of several of Kurosawa's writing projects (including the premiere of Akatsuki no Dassō, and the filming of Tetsu of Jilba and Fencing Master).[10] Around the time of Scandal's production and release, Kurosawa was conceptualising his next film Rashomon (1950). In particular he spent his time thinking about the structure of the titular gate seen in the film by location-scouting in Kyoto and Nara.[11]

Themes

Reality and tabloid journalism

Placing Scandal in the context of the postwar publishing industry, the scholar Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto considers the film to be ahead of its time in tackling the commercially-driven tabloid journalism that proliferated; but writes that the film lacks persuasiveness when the focus shifts from the story of Aoye and Saijo towards the inner struggle of Hiruta.[12] He cites the opening scene of Aoye's landscape painting being critiqued by the woodcutters for its strangeness and originality to Aoye's later critique of people's use of imitation to define themselves. Yoshimoto links these critiques to contrast Aoye's unrealistic painting and the misleading image of the photograph to question the truth of creative reproductions, but concludes that image and reality are not adequately developed to provide an answer to the relationship between them.[13]

The film historian Donald Richie describes the lack of moral ambiguity in the film's depiction of journalists, believing their depiction to be villainous, particularly in comparison to the other characters.[14] To him, the courtroom scene reveals the illusion of the story told through Hiruta's confession, sealing the truth as a kind of redemption.[15] Stuart Galbraith IV notes the pace of the titular scandal's spread through society, particularly the use of montage to replicate the speed of the story's spread. He comments that this builds to the film's final shot where interest in the story is shown to be fleeting to the point that the posters advertising it are torn so they can be replaced by the next story.[9] Richie agrees with the assessment, but argues that the moral focus is ostensibly straightforward unless one understands Hiruta as the film's hero for believing in the truth to save himself—despite the legal affair being over a temporary public fad—even as he loses everything materially.[16]

Idealistic sentiment

Galbraith describes the film's focus on idealism and purity shown through the metaphorical use of stars in its imagery. He cites the Christmas setting and star-decorated Christmas tree, the reflection of stars on water as Aoye and Hiruta drunkenly walk home together, and Aoye's reference to Masako as being "as pure as the stars".[17] Galbraith considers Scandal—of all of Kurosawa's films—to be the most heavily influenced by American cinema, particularly the films of Frank Capra. He compares the setting and singing of "Auld Lang Syne" to It's A Wonderful Life (1946), and the courtroom sequence to Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) and A Free Soul (1931), the latter directed by Clarence Brown. To Galbraith, the comparative scenes in Scandal take the original films' sentimentality and turn them into something more self-reflexive as the characters sombrely reflect on their situation.[17] He believes, however, that despite Shimura's performance, he is written to be too melodramatic, and that he does not regain any agency by confessing at the end.[8]

Like Galbraith, Richie sees the daughter Masako as the film's moral centre. He analyses the Christmas scene wherein Aoye and Miyako celebrate the holiday with Masako and Hiruta's subsequent sentimental reaction to it. The reaction is intensified by Kurosawa's overlaying of Masako's bright face reflected on the glass window of the shoji framing Hiruta. However, he differs from Galbraith in his interpretation of the bar scene where the staff and patrons sing "Auld Lang Syne", believing it to instead represent the capability of all humanity to be good.[18]

Release

Scandal was released in Japan on 30 April 1950.[19] Kurosawa later reflected that his aim of protesting the popularity of the scandal-ridden tabloid press had been mild and ineffectual.[20] The film was released in the United States for the first time in 1964. In Los Angeles, Scandal was first presented as a double feature with Yasujiro Ozu's An Autumn Afternoon (1962). The film was re-released in 1980 by Entertainment Marketing to mixed reviews.[4]

Reception

In her book detailing Japanese cinema during the occupation period, Kyoko Hirano describes the film as a success.[2] The film placed sixth on Kinema Junpo's annual Best Ten list for 1950, one place behind Rashomon.[4]

The film historian Donald Richie and Stuart Galbraith IV both describe the film as being "unbalanced".[16][4]

The movie depicts aspects of so-called kasutori culture, a phenomenon of early postwar Japan that refers to the proliferation of sleazy magazines and cheap alcohol.[21]

Notes

References

Citations

- ^ Shochiku official web site

- ^ a b Hirano 1992, p. 253.

- ^ Richie 1970, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d Galbraith 2002, p. 126.

- ^ Galbraith 1996, p. 347.

- ^ Richie 1970, p. 66.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, pp. 178–179.

- ^ a b Galbraith 2002, p. 123.

- ^ a b Galbraith 2002, p. 125.

- ^ Galbraith 2002, pp. 117–119.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, p. 180.

- ^ Yoshimoto 2000, p. 180.

- ^ Yoshimoto 2000, pp. 180–181.

- ^ Richie 1970, p. 67.

- ^ Richie 1970, p. 68.

- ^ a b Richie 1970, p. 69.

- ^ a b Galbraith 2002, p. 121.

- ^ Richie 1970, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Galbraith 1996, p. 348.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Conrad 2022, pp. 76–77.

Bibliography

Books and journals

- Conrad, David A. (2022). Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan. McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-1-4766-8674-5.

- Galbraith, Stuart IV (1996). The Japanese Filmography: 1900 through 1994. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0032-3.

- Galbraith, Stuart IV (2002). The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. New York: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571199828.

- Hirano, Kyoko (1992). Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: The Japanese Cinema Under the American Occupation. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 1-56098-157-1.

- Kurosawa, Akira (1983). Something Like an Autobiography. Translated by Bock, Audie E. (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-394-71439-4.

- Richie, Donald (1970). The Films of Akira Kurosawa (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01781-1.

- Yoshimoto, Mitsuhiro (2000). Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2519-5.

External links

- Scandal at IMDb

- Scandal at Rotten Tomatoes

- Scandal (in Japanese) at the Japanese Movie Database