Drunken Angel

| Drunken Angel | |

|---|---|

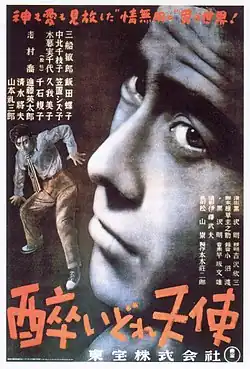

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Akira Kurosawa |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by | Sōjirō Motoki |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Takeo Itō |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Fumio Hayasaka |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Toho |

Release date |

|

Running time | 98 minutes |

| Country | Japan |

| Language | Japanese |

Drunken Angel (醉いどれ天使, Yoidore Tenshi) is a 1948 Japanese yakuza film directed by Akira Kurosawa, and co-written by Kurosawa and Keinosuke Uekusa. Produced by Toho and starring Takashi Shimura and Toshiro Mifune, it tells the story of alcoholic doctor Sanada, and his recidivist yakuza patient Matsunaga. Sanada tries to save Matsunaga from illness and the corruption of the yakuza while Matsunaga finds himself gradually sidelined within the yakuza syndicate and becomes increasingly self-destructive. The film was the first to depict the post–War yakuza and is generally considered to be Kurosawa's first major work.

During the writing of the screenplay Kurosawa and Uekusa fought about Uekusa's growing sympathies with the yakuza due to his regular meetings with a life-model to study for the character. Production began in 1947 amid a series of labour disputes in the Toho company. Filming lasted from November of that year to March 10, 1948. During the production of the film Kurosawa encountered a number of setbacks, including the death of his father in February 1948. The film was the first of sixteen collaborations between Kurosawa and Mifune, and the first collaboration between Kurosawa and Fumio Hayasaka. It was in the production of Drunken Angel that Kurosawa began to think more about music's relationship to the image in film.

Despite encountering some censorship from the Civil Information and Education Section of the Allied occupation government, the film was released in Japan on April 27, 1948 to generally positive reviews. The film won awards for Best Film from Kinema Junpo and Mainichi Shimbun. After the international success of Rashomon (1950) at the 1951 Venice Film Festival, Toho promoted the film abroad. Analyses of Drunken Angel have looked at the pairing of multiple characters and their interactions in the post–War environment, with discussions focussing on the morality of its characters (the titular "drunken angel"), intertextual references to the novels of Fyodor Dostoevsky and contemporary noir fiction, and the symbolic meaning of the sump seen throughout much of the film.

Plot

Sanada is an alcoholic doctor living in a shanty town next to an open sump. He treats a small-time yakuza named Matsunaga—who was injured in a gunfight with a rival syndicate—despite his dislike of organised crime. Sanada diagnoses Matsunaga with tuberculosis; Matsunaga initially reacts violently but the two of them are interrupted by the arrival of Sanda's nurse Miyo. The following day Sanada goes to a bar in the local black market, which Matsunaga controls, and attempts to persuade Matsunaga to give up drinking and smoking. After Matsunaga kicks Sanada out of the bar, Sanada and Miyo discuss the imminent release from prison of Matsunaga's fellow yakuza and sworn brother, Okada, Miyo's abusive ex-boyfriend. Sanada continues treating his other patients, one of whom, a young female student, is making progress against her tuberculosis. After some pestering, Matsunaga agrees to listen to the doctor's advice and quit drinking.

However, with Okada's release, Matsunaga quickly succumbs to peer pressure and slips back into vice together with his fellow yakuza. Angered at the betrayal of his commitment, Sanada rebukes him. Matsunaga finds himself gradually displaced within the yakuza syndicate, and after losing a large amount of money playing chō-han, he collapses and is taken to Sanada's clinic for the evening. Distressed as his lover leaves him and his illness takes a turn for the worse, Matsunaga leaves his apartment and is confronted by Sanada at the open sump. Sanada beseeches Matsunaga to continue his treatment, while Matsunaga has a vision of his own corpse trying to kill him. Okada shows up at the clinic and threatens to kill the doctor if he does not tell him where to find Miyo, and while Matsunaga stands up for the doctor and gets Okada to leave, he realises that his sworn brother cannot be trusted.

Hoping to resolve the issue, Matsunaga goes to the home of the boss of his syndicate but overhears a discussion in which Okada says he intends to sacrifice him as a pawn in the war against a rival syndicate. Distressed and self-destructive, Matsunaga orders a drink from Gin, a local barmaid, who tries to persuade him to seek treatment in the countryside. The boss returns the territory of the black market to Okada, who orders the storeowners in his territory to refuse service to Matsunaga. He goes to Okada's apartment; there, he finds the yakuza with his former lover, and angrily tries to stab Okada, but starts to cough up blood. Okada then stabs him in the chest, and Matsunaga stumbles outside before he succumbs to his wounds and dies.

Okada is later arrested for the murder, but Matsunaga's boss refuses to pay for his funeral. Gin, who had feelings for Matsunaga, pays for it instead and tells Sanada that she plans to take Matsunaga's ashes to be buried on her father's farm, where she had offered to live with him. The doctor retorts that while he understands how she feels, he cannot forgive Matsunaga for throwing his life away. Another of his patients, the female student, arrives and reveals that her tuberculosis is cured. The doctor happily leads her to the market to buy her sweets.

Cast

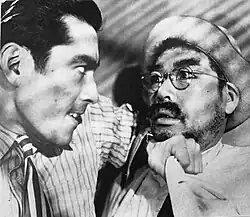

- Takashi Shimura as Doctor Sanada

- Toshiro Mifune as Matsunaga

- Reizaburo Yamamoto as Okada

- Michiyo Kogure as Nanae

- Chieko Nakakita as Nurse Miyo

- Eitarō Shindō as Takahama

- Noriko Sengoku as Gin

- Shizuko Kasagi as singer

- Masao Shimizu as Oyabun

- Yoshiko Kuga as schoolgirl

Production

Development

Drunken Angel was made in the context of a series of labour disputes with the Toho company. The powerful trade union had managed the production of films, with Kurosawa's prior films No Regrets for Our Youth (1946) and One Wonderful Sunday (1947) requiring the approval of the union. By the end of 1947, the union influence that had been exerted over the content of films produced by Toho began to wane following a series of less profitable releases. As a result, Kurosawa was able to produce the film with minimal interference from the studio and its union.[1] Kurosawa co-wrote the film with his childhood friend Keinosuke Uekusa in their second and last collaboration together.[2] While staying at an inn at the seaside resort Atami, Kurosawa noticed that the prow of a sunken concrete ship was being used as a diving board by local children. Seeing it as an apt metaphor for Japan's defeat in the Second World War, this image became the open sump seen in Drunken Angel.[3] Kurosawa intended to write the film to report on—and denounce—the growing power of the yakuza in post–War Japan.[4][5]

During writing of the screenplay, Uekusa met up with a member of the yakuza to develop the character of Matsunaga. While he and Kurosawa had intended for his counterpart to be a morally upright humanistic young doctor, the character was difficult to conceptualise and was changed when the two remembered an encounter they had with an unlicensed alcoholic doctor in Tokyo's black market district.[6] Having spent five days prior to the doctor's change in character unsure of how to progress the script, they finished writing the film in about a day.[7] However, Uekusa's meetings with the yakuza character model caused him to sympathise with their way of life to the degree that he and Kurosawa eventually argued over his sympathies.[8] Despite the speed with which the two of them finished the script, Kurosawa recalled the two of them sharing a rocky relationship during its development. Although they remained friends, the two of them separated and did not collaborate again following the script's completion.[9]

Pre-production

Pre-production began in November 1947.[10] Toshiro Mifune was cast after Kurosawa saw his performances in Snow Trail (1947) and Kajirō Yamamoto's These Foolish Times (1947).[11][12] Kurosawa had seen Mifune's audition to work at the Toho company in 1946 and had directly intervened in the hiring process in order to secure Mifune a position; the jury had wrongly interpreted the actor's wild behaviour during the audition as disrespect.[13] Drunken Angel became the first of their 16 collaborations together.[14] This was also the first film where Kurosawa worked with Yoshiro Muraki.[15] The film was built around a pre-existing set, used in These Foolish Times.[1] This set was of a shopping street with a black market, which Kurosawa credits for the origin of his interest in dissecting the character of yakuza gang members.[8]

Production

The film was produced by Toho and shot in black-and-white.[16] Filming began in November 1947.[10] During the course of production, Kurosawa faced a number of personal and professional problems. Toho executives pressured Kurosawa to finish production quickly, anxious to see more films in cinemas before any more potential strikes, and actress Keiko Orihara became ill shortly into production—she was replaced by Chieko Nakakita in January 1948. Additionally, in February, Kurosawa's father Isamu died at the age of 83. Kurosawa felt too pressured to be able to return to Akita Prefecture during the final weeks of shooting to be with his father.[10]

Takashi Shimura loosely based his character of the doctor on the performance of Thomas Mitchell in Stagecoach (1939). Despite Shimura's role as the protagonist, Kurosawa later expressed difficulty in being able to contain Mifune's performance as the gangster so that he did not dominate the film with his screen presence.[11] Kurosawa also praised the acting of Reizaburo Yamamoto, although he described being too afraid to approach him for some time due to his "frightening eyes".[17] Filming ended on March 10, 1948.[11] A 150-minute cut of the film was made but never released; all existing negatives and prints are of the 98 minute cut.[16]

Music

Drunken Angel marked Kurosawa's first collaboration with composer Fumio Hayasaka. The two agreed on much of the film's composition. Kurosawa wrote memos (published in the April 1948 edition of Eiga Shunshu) that detailed his changing attitude towards the use of music in his films, becoming more conscious of its inclusion by matching it to parts of the script during the film's writing.[18] For Okada's introductory scene, Kurosawa and Hayasaka wanted to use the song "Mack the Knife" from The Threepenny Opera, but found that it was copyrighted and the studio was unwilling to pay for the rights.[19][20] The use of cheerful-sounding song "The Cuckoo Waltz" was designed to juxtapose the film's low-point of Matsunaga being rejected from different neighbourhood establishments.[20] Kurosawa thought to use this song when, on the day he received news of his father's death, he heard the music over a loudspeaker and found that it intensified his own grief.[21] Supposedly the director and composer shook hands after discovering that they had had the same idea separately but simultaneously. The film's sound recorder was Wataru Konuma.[20]

Occupation censorship

At the time of Drunken Angel's production, there were limitations placed on Japanese films by the Allied occupation government. Films were encouraged to promote individual liberties and Japan's demilitarisation, while forbidden from promoting nationalistic or feudal values. From 1946, the Civil Information and Education Section enforced a double censorship of completed scripts during pre-production and completed films following the final edit.[22] The occupation's censors required Kurosawa to rewrite several portions of the film mostly due to ethical concerns; for example, a mention of suicide was cut, and complaints were made concerning the film's frank depiction of prostitution and black markets.[23] The film's ending was also changed; originally the doctor Sanada drove Matsunaga's corpse around the Tokyo slum.[24][25] Matsunaga's manner of death also underwent several re-writes within each of which he was killed by different people.[24]

Themes

Post–War dual identity

In his study of Kurosawa's filmography, Stuart Galbraith IV sees the gangster Matsunaga and Doctor Sanada as linked by their illness. To Sanada, Matsunaga represents the "chaotic temptations of postwar Japan", which Sanada relates to his own past behaviour. However, Matsunaga equally stands for the corrupt criminality of the period's social chaos that Sanada reviles.[26] Galbraith believes that the doctor is the film's titular 'drunken angel' for seeking the improvement of others over himself despite his self-hatred; the film historian Donald Richie agrees, but believes that Matsunaga and Sanada "are angels to each other."[27][4] To Richie, Matsunaga's death, doused in white paint, represents a blurring of morality and an apotheosis for the character.[28] Matsunaga is also paired with various women in the film: he and Sanada's nurse Miyo each have a relationship with his old yakuza boss Okada, however, she resists returning to her old life; additionally, one of Sanada's patients is also afflicted with tuberculosis, but is able to overcome her illness. Both Matsunaga and Sanada have women that love and care for them in what Galbraith terms a "Hitchcock-like parallelism".[29] It is these women that historian David Conrad believes best embody the future, despite their marginal role in comparison to Kurosawa's earlier films No Regrets for Our Youth and One Wonderful Sunday.[25]

The film scholar James Goodwin's perspective on the film's dual identity is informed by his reading of the psychological doubling between Matsunaga and Sanada. He recalls Sanada's paradoxical commitment to alleviating his patients' illnesses which ends their need for his services, while he himself remains an unhealed alcoholic. Similarly, when his condition deteriorates, Matsunaga hallucinates raising his own corpse from a coffin, only to be scorned by it. Both characters are positioned as sharing, "a vital [emotional] bond."[30] Richie identifies Matsunaga's hallucinatory sequence with the relationship he shares with the nurse Miyo to the yakuza Okada. The sequence follows a scene where Miyo had been recognised by the yakuza; she is then identified by an edit that sees Mifune watching a doll floating in the sump. As he hallucinates, the sump transforms into the open sea, a change in location that signifies both characters' desires to escape.[31] Richie describes the film's final scene between Sanada and Gin as a misunderstanding, since the conflict within Matsunaga was internal, they are unable to understand that his violent death was an attempt to eradicate the evil of his past self.[32] However, Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto considers Kurosawa's attempt at moral complexity to be a mistake, since despite his alcoholism, Sanada remains the idealistic moral anchor of the film.[33]

Stephen Prince, in his analysis of Kurosawa's filmography, considers the "double loss of identity" present within the film. One loss which requires the individual to forge a new sense of self by separating themselves from old institutions, such as the nation and yakuza which erode personal identity. The other being symptomatic of a "national schizophrenia" that has resulted from the Americanisation of Japan which also represents an affront to the individual.[34] In the film the young are cut off from the past but still bound by its social mores.[35] Scholar James Maxfield examines the relationship formed between yakuza within the film. To him, Sanada's assertion that the code of honour observed by the yakuza is only built on money is proved correct when Matsunaga's confrontation with his syndicate's boss shows the former wearing shoes on tatami with money strewn around him, indicating the two men's mutual disrespect to each other.[36] As Matsunaga continues to lose his status, Maxfield rejects any moral reasoning for Matsunaga's confrontation with Okada, rather positing that he is motivated by pride and selfishness.[37] Through this motivation, Maxfield sees the link in Sanada and Matsunaga's relationship: that because of his identification with Matsunaga's behaviour, Sanada loves him and tries to heal his own past wounds.[38]

Open sump imagery

Goodwin, Galbraith, and the film critic Mark Schilling, each view the open sump as a representative of the desolate post–War world.[39][10][40] Maxfield sees in the sump specifically the source of evil within post–War society.[41] However, both Galbraith and Richie see in the sump an additional psychological dimension, viewing the characters' reflections on the murky water as an indication of their mentality, with Matsunaga throwing his carnation away as a symbol that he has discarded his life.[10][42] Yoshimoto agrees with this psychological assessment of the sump, commenting that its appearance structures the film and establishes a psychological profile of Matsunaga that is reflected by his eventual mental breakdown as his image appears split between a three-panel mirror when he fights Okada.[43]

Richie additionally identifies the sump with a metaphysical condition as well as illness directly. Citing the scene where Matsunaga collapses after voluntarily returning to the clinic at night, because the camera movement from the clinic across the sump occurs after Matsunaga has declared his intent to reform himself, the movement implies a more ambiguous future.[42] Prince links this sequence with a prior scene containing a similar series of dissolves that links Miyo to the sump, an image that constrains both her and Matsunaga to a decaying social space.[44] He writes that the narrative and spatial confinement of much of the film close to the sump returns the film's action to sickness, posing the question of how recovery can emerge from a humane ethic under post–War conditions.[35]

Intertextuality

David Desser points to Drunken Angel as an early example among Kurosawa's films of demonstrating how Western culture impacted Japanese society, i.e., that it represents an adaptation of different modes of thought from American gangster stories and the existentialist literature of Fyodor Dostoevsky.[45] Similarly, Goodwin writes on the intertextual qualities of the film and Kurosawa's references to different artistic mediums. He considers the final fight between Matsunaga and his rival among spilt paint to be a kind of "action painting" and also compares Drunken Angel's literary qualities to the novels of Dostoevsky.[46] In particular, Goodwin focusses on a process of psychological doubling found in Dostoevsky's novels, wherein internal paradoxes and contrasting personalities—such as those of Matsunaga and Sanada—form a dialogue on suffering and human nature.[47] In comparing characterisations, the film theorist Noël Burch compares Sanada and Matsunaga to Prince Mishkin and the characters of The Lower Depths for their "stubborn fantasising" amidst a series complex social obligations.[48] To Conrad, Kurosawa's focus on illness in a world of yakuza and panpan girls, so employing the genre trappings of film noir, served to criticise American governance via the aesthetics of American culture.[49]

Release

Theatrical

Drunken Angel was released in Japanese cinemas on April 27, 1948.[20] Upon the film's completion, Kurosawa went to Akita to observe the memorial services of his father, but was recalled as the Toho union's strikes had escalated.[50] The new company president, Tetsuzo Watanabe, vetoed union-supported films and fired 1,200 employees. In response, the union occupied the building, halting production on new films. The strikers were placed under siege by police and the American military, the studio ended their pay, and shut down the filming lot on June 1. In need of money, Kurosawa directed two stage productions, one of Anton Chekhov's A Marriage Proposal, and the other an adaptation of Drunken Angel.[51] Kurosawa soon left the studio, being both disillusioned by executives' attitudes to the union, and by the state of siege the occupying strikers were put under. In his memoir Kurosawa writes that the studio, "I had thought was my home actually belonged to strangers".[52]

The film was one of only four productions that Toho released in 1948, reflecting the studio management's priorities amidst disruptive strike action.[53] Toho promoted the release of the film throughout the 1950s, with it premiering in the United States in January 1960 as part of a nine-film release licensed by Brandon Films.[20]

Home media

A VHS version of Drunken Angel was released by Home Vision Cinema.[54] The Criterion Collection released a Blu-ray version of the film alongside other Kurosawa films in a 2009 box set.[55]

Reception

Critical response

Contemporary opinion

Upon release in Japan, the film received positive reviews.[20] However, there were some critics who did not believe the film went far enough in condemning the activities of its protagonist or the yakuza world at-large.[56] According to Kurosawa, critics referred to him as a journalistic filmmaker.[57] Japanese audiences were surprised by Mifune's emotional performance, a form of expressiveness that was not generally seen in Japanese cinema of the time. Galbraith compares the impact of, and audiences' positive reaction to, Mifune's performance with Marlon Brando's in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951).[11] Japanese critics have pointed to Drunken Angel as embodying the post–War epoch in Japanese society, with comparisons made to Bicycle Thieves (1948) and Paisan (1946).[58]

In a 1954 article for Sight and Sound, prior to any wide international release, filmmaker Jay Leyda discussed Drunken Angel in the context of growing international interest in Japanese cinema, praising its range, cinematography, and fluid structure.[59] Writing just prior to the American release, Bosley Crowther's 1959 review for The New York Times, cites the film's creation of an unpleasant atmosphere in his positive appraisal of its symbolic moral conflict. He also gives a positive account of the acting and Kurosawa's "forceful imagery", despite criticising some of the film's unoriginal formal methods and clichés.[60] A review in Variety magazine compared Drunken Angel to Italian neorealist cinema in its depiction of contemporary Japanese society; the review also praised the film's acting and pursuit of morality within the post–War devastation.[20] However, a negative review by Dwight Macdonald in Esquire negatively compared the film to the simultaneous American releases of Ikiru (1952) and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger's Tail (1945), criticising the film as an "embarrassingly familiar gangster melodrama."[61]

Retrospective opinion

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Drunken Angel has a 94% approval rating.[62] A review in Slant Magazine gave the film three stars out of four, praising Kurosawa's dynamic cinematism.[63] In a 2007 essay for The Criterion Collection, East Asian scholar Ian Buruma writes on the changes taking place within Japanese society as seen in Drunken Angel. He perceives the lack of Allied soldiers and panpan girls within a narrative where traditional 'feudal' loyalties to the state have been used to justify crime and immoral behaviour as an effective criticism of the pre– and post–War social orders.[64] Writing for New York Press in 2010, film critic Armond White praised the film's handling of the balance between remorse and grief. Although he considers some of its symbolism obvious, he writes appreciatingly of its deployment and favourably compares the film to later social and crime dramas.[65]

Awards and accolades

| Award | Date | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mainichi Film Awards | 1948 | Best Film | Drunken Angel | Won | [20][66] |

| Best Cinematography | Takeo Ito | ||||

| Best Music | Fumio Hayasaka | ||||

| Kinema Junpo | 1948 | Best Film of the Year | Drunken Angel | Won | [20] |

Legacy

Drunken Angel is often considered Kurosawa's first major work.[1][58] Leyda credits Drunken Angel as the precursor responsible for the entry of Rashomon (1950) into the 1951 Venice Film Festival, and thus exposing non-Japanese audiences to post–War Japanese cinema.[67] Kurosawa later reflected on the film's structural weakness which he mostly attributed to Mifune's intense screen-presence, one which overshadowed Shimura's role as the moral centre of the film.[68] However, the director saw it as the first film where he began to think about the image's relationship to music, and remembered it happily as the first film that was his own, i.e., the first that was free from the interference of the studio, union, and wartime censorship.[69][58] In a 1960 interview with Donald Richie, Kurosawa considered the film's popularity at the time of its release to be due to it being the only film in cinemas that took an interest in its characters.[57] Kurosawa later referred to Drunken Angel as the first of his films that used dynamic compositions.[70]

In Mark Schilling's study on yakuza films, he cites Drunken Angel as the first to depict post–War yakuza. Schilling notes that the film does not follow many of the genre expectations within the genre, which he attributes to Kurosawa's humanism, examining how the world around the yakuza influences their actions.[71] In a 2002 interview, actor Bunta Sugawara likewise referenced the film as the first post–War yakuza movie.[72] Conrad cites Drunken Angel as the first post–War film with a yakuza protagonist.[14]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c Galbraith 2002, p. 91.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, p. 155.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, pp. 155–156.

- ^ a b Richie 1970, p. 49.

- ^ Galbraith 2002, p. 92.

- ^ Galbraith 2002, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, p. 158.

- ^ a b Kurosawa 1983, p. 156.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, pp. 158–159.

- ^ a b c d e f Galbraith 2002, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d Galbraith 2002, p. 95.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, p. 161.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, pp. 159–161.

- ^ a b Conrad 2022, p. 56.

- ^ Wild 2014, p. 88.

- ^ a b Galbraith 1996, p. 155.

- ^ Galbraith 2002, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Galbraith 2002, p. 96.

- ^ Harris 2013, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Galbraith 2002, p. 97.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Hirano 1992, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Hirano 1992, pp. 75, 77.

- ^ a b Hirano 1992, p. 77.

- ^ a b Conrad 2022, p. 61.

- ^ Galbraith 2002, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Galbraith 2002, p. 93.

- ^ Richie 2005, p. 167.

- ^ Galbraith 2002, pp. 93–94.

- ^ Goodwin 1994, p. 61.

- ^ Richie 1970, p. 51.

- ^ Richie 1970, p. 52.

- ^ Yoshimoto 2000, p. 139.

- ^ Prince 1991, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Prince 1991, p. 89.

- ^ Maxfield 1993, p. 25.

- ^ Maxfield 1993, p. 26.

- ^ Maxfield 1993, p. 22.

- ^ Goodwin 1994, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Schilling 2003, p. 314.

- ^ Maxfield 1993, p. 23.

- ^ a b Richie 1970, p. 50.

- ^ Yoshimoto 2000, p. 138.

- ^ Prince 1991, p. 81.

- ^ Desser 1983, pp. 5, 133.

- ^ Goodwin 1994, pp. 11, 58.

- ^ Goodwin 1994, pp. 59–62, 86.

- ^ Burch 1979, p. 296.

- ^ Conrad 2022, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, p. 164.

- ^ Galbraith 2002, p. 98.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, pp. 166–168.

- ^ Hirano 1992, p. 234.

- ^ Richie 2005, p. 263.

- ^ Guerrasio 2009.

- ^ Hirano 1992, p. 282.

- ^ a b Cardullo 2008, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Richie 1970, p. 47.

- ^ Leyda 1954, pp. 74–77.

- ^ Crowther 1959.

- ^ Macdonald 1960, p. 36.

- ^ Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ Croce 2007.

- ^ Buruma 2007.

- ^ White 2010.

- ^ Mainichi Shimbun.

- ^ Leyda 1954, p. 74.

- ^ Prince 1991, p. 88.

- ^ Kurosawa 1983, p. 196.

- ^ Cardullo 2008, p. 29.

- ^ Schilling 2003, p. 314.

- ^ Schilling 2003, p. 132.

Bibliography

Books and journals

- Burch, Noël (1979). To the Distant Observer: Form and meaning in the Japanese cinema. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03877-6.

- Cardullo, Bert, ed. (2008). Akira Kurosawa: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-57806-996-5.

- Conrad, David A. (2022). Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan. McFarland & Co. ISBN 978-1-4766-8674-5.

- Desser, David (1983). The Samurai Films of Akira Kurosawa. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press. ISBN 0-8357-1924-3.

- Galbraith, Stuart IV (1996). The Japanese Filmography: 1900 through 1994. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0032-3.

- Galbraith, Stuart IV (2002). The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune. New York: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0571199828.

- Goodwin, James (1994). Akira Kurosawa and Intertextual Cinema. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4661-7.

- Harris, Michael (2013). "Jazzing in the Tokyo slum: music, influence, and censorship in Akira Kurosawa's Drunken Angel". Cinema Journal. 53 (1): 52–74. doi:10.1353/cj.2013.0067. S2CID 193175605.

- Hirano, Kyoko (1992). Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: The Japanese Cinema Under the American Occupation. Smithsonian Institution. ISBN 1-56098-157-1.

- Kurosawa, Akira (1983). Something Like an Autobiography. Translated by Bock, Audie E. (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-394-71439-4.

- Maxfield, James (Fall 1993). "The Moral Ambiguity of Kurosawa's Early Thrillers". Film Criticism. 18 (1). Allegheny College: 20–35. JSTOR 44075989.

- Prince, Stephen (1991). The Warrior's Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa (Revised and Expanded ed.). Princeton University Press (published 1999). ISBN 978-0-691-01046-5.

- Richie, Donald (1970). The Films of Akira Kurosawa (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-01781-1.

- Richie, Donald (2005) [2001]. A Hundred Years of Japanese Film (Revised ed.). Tokyo: Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 978-4-7700-2995-9.

- Schilling, Mark (2003). The Yakuza Movie Book : A Guide to Japanese Gangster Films. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 1-880656-76-0.

- Wild, Peter (2014). Akira Kurosawa. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-78023-343-7.

- Yoshimoto, Mitsuhiro (2000). Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-2519-5.

News and magazines

- Crowther, Bosley (December 31, 1959). "The Screen: Japanese 'Drunken Angel'; Kurosawa Drama at Little Carnegie". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 9, 2023. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- Leyda, Jay (October–December 1954). "The Films of Kurosawa". Sight and Sound. Vol. 24, no. 2. London: The British Film Institute. ISSN 0037-4806.

- Macdonald, Dwight (May 1, 1960). "Films: A masterpiece—and some others". Esquire. ISSN 0960-5150. Archived from the original on April 12, 2020. Retrieved August 15, 2025.

Web

- Buruma, Ian (November 19, 2007). "Drunken Angel: The Spoils of War". Criterion Collection. Archived from the original on February 15, 2025. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- Croce, Fernando F. (November 27, 2007). "Review: Drunken Angel". Slant Magazine. Archived from the original on August 6, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- Guerrasio, Jason (September 16, 2009). "Criterion Announces Kurosawa Box Set". Filmmaker. Archived from the original on April 17, 2024. Retrieved April 7, 2025.

- 毎日映画コンクール 第3回(1948年) [Mainichi Film Awards: 3rd Ceremony (1948)]. Mainichi Shimbun (in Japanese). Archived from the original on January 24, 2025. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- "Drunken Angel". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on April 20, 2025. Retrieved August 16, 2025.

- White, Armond (January 20, 2010). "AK 201: Kurosawa to the Rescue". New York Press. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2025.

External links

- Drunken Angel - Japanese With English Subtitles, online video (1 hour, 38 minutes, 14 seconds), at Archive.org