Portal:Judaism

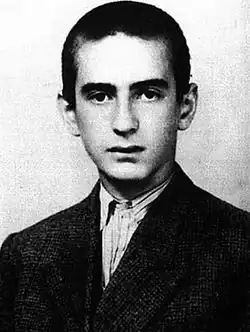

The Judaism PortalJudaism (Hebrew: יַהֲדוּת, romanized: Yahăḏūṯ) is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of observing the Mosaic covenant, which they believe was established between God and the Jewish people. The religion is considered one of the earliest monotheistic religions. Jewish religious doctrine encompasses a wide body of texts, practices, theological positions, and forms of organization. Among Judaism's core texts is the Torah—the first five books of the Hebrew Bible—and a collection of ancient Hebrew scriptures. The Tanakh, known in English as the Hebrew Bible, has the same books as Protestant Christianity's Old Testament, with some differences in order and content. In addition to the original written scripture, the supplemental Oral Torah is represented by later texts, such as the Midrash and the Talmud. The Hebrew-language word torah can mean "teaching", "law", or "instruction", although "Torah" can also be used as a general term that refers to any Jewish text or teaching that expands or elaborates on the original Five Books of Moses. Representing the core of the Jewish spiritual and religious tradition, the Torah is a term and a set of teachings that are explicitly self-positioned as encompassing at least seventy, and potentially infinite, facets and interpretations. Judaism's texts, traditions, and values strongly influenced later Abrahamic religions, including Christianity and Islam. Hebraism, like Hellenism, played a seminal role in the formation of Western civilization through its impact as a core background element of early Christianity. (Full article...) Selected Article Night is a work by Elie Wiesel (pictured) about his experience with his father in the Nazi concentration camps at Auschwitz and Buchenwald in 1944–1945. In just over 100 pages of a narrative described as devastating in its simplicity, Wiesel writes about the death of God and his own increasing disgust with humanity, reflected in the inversion of the father-child relationship as his father declines to a helpless state and Wiesel becomes his resentful caregiver. He was 16 years old when Buchenwald was liberated by the U.S. Army in April 1945, too late for his father who died in the camp after a beating. After some difficulty finding a publisher, Wiesel's work appeared in Yiddish in 1955 and French in 1958, and in September 1960 was published in English by Hill and Wang. Fifty years later it is regarded as one of the bedrocks of Holocaust literature. It is the first book in a trilogy—Night, Dawn, Day—marking Wiesel's transition from darkness to light, according to the Jewish tradition of beginning a new day at nightfall. "In Night," he said, "I wanted to show the end, the finality of the event. Everything came to an end—man, history, literature, religion, God. There was nothing left. And yet we begin again with night." (Read more...) Did You Know?Did you know...

Related Categories

Featured Articles

Related PortalsHistory ArticleRudolf Vrba was Professor in the Department of Pharmacology and Therapeutics at the University of British Columbia in Canada. In April 1944, Vrba and Alfréd Wetzler became the second and third of only five Jews to escape successfully from the German death camp at Auschwitz and pass information to the Allies about the mass murder that was taking place there. The 32 pages of information that the men dictated to horrified Jewish officials in Slovakia became known as the Vrba–Wetzler report. It is regarded as one of the most important documents of the 20th century, because it was the first detailed information about the death camp to reach the Allies that they accepted as credible. Although the report's release to the public was controversially delayed until after the mass transport of 437,000 Jews from Hungary to Auschwitz had begun on May 15, 1944, it is nevertheless credited with having saved many lives. Yehuda Bauer, Professor of Holocaust Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has called Vrba "one of the Heroes of the Holocaust". (Read more...) Picture of the Week Credit: Ori229 (talk)

In the News

Featured Quote

WikiProjects

Things You Can Do

Weekly Torah PortionShoftim (שופטים)

Deuteronomy 16:18–21:9

“Justice, justice shall you pursue, that you may thrive and occupy the land that the Lord your God is giving you.” (Deuteronomy 16:20.)

Moses directed the Israelites to appoint magistrates and officials for their tribes to govern the people with justice, impartially, without bribes. “Justice, justice shall you pursue,” he said. Moses warned the Israelites against setting up a sacred post beside God’s altar or erecting a stone pillar. Moses warned the Israelites against sacrificing an ox or sheep with any serious defect. If the Israelites found a person who worshiped other gods, the Sun, the Moon, or any celestial body, then they were to make a thorough inquiry, and if they established the fact on the testimony of two or more witnesses, then they were to stone the person to death, with the witnesses throwing the first stones. If a case proved too baffling for them to decide, then they were promptly to go to the place that God would choose for God's shrine, appear before the priests or the magistrate in charge and present their problem, and carry out any verdict that was announced there without deviating either to the right or to the left. They were to execute any man who presumptuously disregarded the priest or the magistrate, so that all the people would hear, be afraid, and not act presumptuously again.  If, after the Israelites had settled the land, they decided to set a king over them, they were to be free to do so, taking an Israelite chosen by God. The king was not to keep many horses, marry many wives, or amass silver and gold to excess. The king was to have the priests write for him a copy of this Teaching to remain with him and read all his life, so that he might learn to revere God and observe these laws faithfully. He would thus not act haughtily toward his people nor deviate from the law, and as a consequence, he and his descendants would enjoy a long reign. The Levites were to have no territorial portion, but were to live only off of offerings, for God was to be their portion. In exchange for their service to God, the priests were to receive the shoulder, cheeks, and stomach of sacrifices, the first fruits of the Israelites’ grain, wine, and oil, and the first shearing of sheep. Levites were to be free to come from their settlements to the place that God had chosen as a shrine to serve in the name of God with their fellow Levites, and there they were to receive equal shares of the dues. The Israelites were not to imitate the abhorrent practices of the nations that they were displacing, consign their children to fire, or act as an augur, soothsayer, diviner, sorcerer, one who casts spells, one who consults ghosts or familiar spirits, or one who inquires of the dead, for it was because of those abhorrent acts that God was dispossessing the former residents of the land. God would raise a prophet from among them like Moses, and the Israelites were to heed him. When at Horeb the Israelites asked God not to hear God’s voice directly, God created the role of the prophet to speak God’s words, promising to hold to account anybody who failed to heed the prophet’s words. But any prophet who presumed to speak an oracle in God’s name that God had not commanded the prophet to utter, or who spoke in the name of other gods, was to die. This was how the people were to determine whether the oracle was spoken by God: If the prophet spoke in the name of God and the oracle did not come true, then that oracle was not spoken by God, the prophet had uttered it presumptuously, and the people were not to fear him. When the Israelites had settled in the land, they were to divide the land into three parts and set aside three cities of refuge, so that any manslayer could have a place to which to flee. And if the Israelites faithfully observed all the law and God enlarged the territory, then they were to add three more towns to those three. Only a manslayer who had killed another unwittingly, without being the other’s enemy, might flee there and live. For instance, if a man went with his neighbor into a grove to cut wood, and as he swung an ax to cut down a tree, the ax-head flew off the handle and struck and killed the neighbor, then the man could flee to one of the cities of refuge and live. If, however, one who was the enemy of another lay in wait, struck the other a fatal blow, and then fled to a city of refuge, the elders of the slayer’s town were to have the slayer turned over to the blood-avenger to be put to death. The Israelites were not to move their countrymen’s landmarks, set up by previous generations, in the property that they were allotted in the land. An Israelite could be found guilty of an offense only on the testimony of two or more witnesses. If one person gave false testimony against another, then the two parties were to appear before God and the priests or magistrates, the magistrates were to make a thorough investigation, and if the magistrates found the person to have testified falsely, then they were to do to the witness as the witness schemed to do to the other. Before the Israelites joined battle, the priest was to tell the troops not to fear, for God would accompany them to do battle against their enemy. Then the officials were to ask the troop whether anyone had built a new house but not dedicated it, planted a vineyard but never harvested it, paid the bride price for a wife but not yet married her, or become afraid and disheartened, and all these they were to send back to their homes. When the Israelites approached a town to attack it, they were to offer it terms of peace, and if the town surrendered, then all the people of the town were to serve the Israelites as forced labor. But if the town did not surrender, then the Israelites were to lay siege to the town, and when God granted victory, kill all its men and take as booty the women, children, livestock, and everything else in the town. Those were the rules for towns that lay very far from Israel, but for the towns of the nations in the land — the Hittites, Amorites, Canaanites, Perizzites, Hivites, and Jebusites — the Israelites were to kill everyone, lest they lead the Israelites into doing all the abhorrent things that those nations had done for their gods. When the Israelites besieged a city for a long time, they could eat the fruit of the city’s trees, but they were not to cut down any trees that could yield food. If, in the land, someone slain was found lying in the open, and the slayer could not be determined, then the elders and magistrates were to measure the distances from the corpse to the nearby towns. The elders of the town nearest to the corpse were to take a heifer that had never been worked down to an ever-flowing wadi and break its neck. The priests were to come forward, all the elders were to wash their hands over the heifer whose neck was broken, and the elders were to declare that their hands did not shed the blood nor their eyes see it done. The elders were to ask God to absolve the Israelites, and not let guilt for the blood of the innocent remain among them, and they would be absolved of bloodguilt. Hebrew and English text TopicsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals

| |||||||||||||||