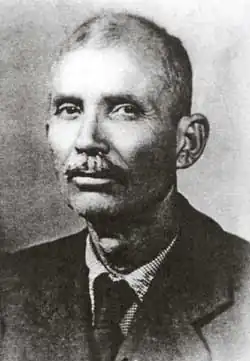

Panko Brashnarov

Panko Brashnarov | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 9 August 1883 |

| Died | 13 July 1951 (aged 67) |

Panko Brashnarov (Bulgarian and Macedonian: Панко Брашнаров, romanized: Panko Brašnarov; 9 August 1883 – 13 July 1951) was a revolutionary, member of the left-wing of the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO) and IMRO (United). As with many other IMARO members of the time, historians from North Macedonia consider him an ethnic Macedonian,[1] whereas historians in Bulgaria consider him a Bulgarian.[2] The name of Brashnarov was a taboo in Yugoslav Macedonia, but he was rehabilitated during the 1990s, after the country gained its independence.

Biography

He was born in Veles (then known by the name Köprülü) in the Kosovo vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia) on 9 August 1883,[3] where he graduated from a Bulgarian Exarchate's primary school. Subsequently, Brashnarov graduated from the Bulgarian pedagogical school in Skopje.[4] Later he worked as a Bulgarian Exarchate teacher.[5] He joined the Internal Macedonian-Adrianople Revolutionary Organization (IMARO).[6] In 1903 he took part in the Ilinden Uprising.[5] After the uprising, he was part of the leftist (federalist) faction of IMARO.[6] In 1908 he joined the People's Federative Party (Bulgarian Section).[7] He was mobilized in the Bulgarian army during the First World War and participated in the battles of the Macedonian front.[3] After Bulgaria lost the war, the Bulgarian occupation of Vardar Macedonia ended and Brashnarov remained in the new Kingdom of Yugoslavia. In 1919, he joined the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. In 1925 in Vienna, Brashnarov was elected as one of the leaders of Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (United).[7][8] Because of his political convictions, he was sentenced to seven years in prison in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. While he was imprisoned in Maribor, in an article in the newspaper Makedonsko Delo from 25 June 1929, Dimitar Vlahov referred to him as a Macedonian Bulgarian.[9][10] After his release in 1936 he remained politically passive.

When Bulgaria occupied and later annexed Vardar Banovina in 1941, he was one of the founders of the Bulgarian Action Committees.[11] Until 1943, Brashnarov worked again as a Bulgarian teacher. In the same year, Brashnarov became politically active again and joined the Macedonian partisan movement there fighting against the Axis Powers.[7] At that time the Yugoslav communists recognized a separate Macedonian nationality to stop the fears of the local population that they would continue the former Yugoslav policy of forced serbianization, but they did not support the view that the Macedonian Slavs are Bulgarians, because that meant in practice, the area should remain part of the Bulgaria after the war.[12] On 2 August 1944, the first session of the Antifascist Assembly of the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM) took place at the St. Prohor Pčinjski monastery. Brashnarov served as vice-president of the Presidium and as the first speaker.[6][7] The modern Macedonian state was officially proclaimed as a federal state within Josip Broz Tito's Yugoslavia, receiving recognition from the Allies in 1945. The new Macedonian authorities had a primary goal to de-Bulgarize the Macedonian Slavs and to create a separate Macedonian consciousness that would inspire identification with Yugoslavia.[12]

The Tito–Stalin split in 1948 led to the persecution of pro-Bulgarian Macedonians, such as him and Pavel Shatev.[6] Being disappointed by the policy of the authorities, Brashnarov complained of it in letters in the same year to Joseph Stalin and to Georgi Dimitrov and asked for help, maintaining better relations with Bulgaria and the Soviet Union, and opposing the serbianization and Bulgarophobia spread amongst the Macedonian people.[13] He did so together with Shatev. Brashnarov regarded the Macedonian alphabet as being under the influence of Serbian.[6] He was arrested in 1950 under the accusation of "organizing an illegal group to support the Soviet Union in its conflict with Yugoslavia".[14] Afterwards he was sent to the Goli Otok labor camp in the next year where he served for ten days, until his death on 13 July 1951.[15][16] According to Venko Markovski, his family honored him with a communist-style inscription in the Veles cemetery.[17] Two years after his death, he was buried in the cemeteries in Zagreb. His grave was found in 2011 in Zagreb at the Mirogoj Cemetery by a Macedonian team of journalists, where he was reburied in a mass grave of prisoners from Goli Otok after two exhumations in 1971 and the 1980s.[16]

Legacy

The name of Brashnarov was taboo in the SR Macedonia during the period 1950–1990, because of the obligatory pro-Serbian and anti-Bulgarian tendency among the "socialist" Yugoslav Macedonian historians, but he was rehabilitated in the Republic of Macedonia during the 1990s after the country gained its independence.[6][18] In 2004, the SDSM local government erected a statue of him in Veles.[15]

Although he was liked by the historiography in Communist Bulgaria as a left-wing pro-Bulgarian politician, after the fall of communism he has been criticized by some right-wing nationalist historians there as a late repented Macedonian Communist apostate.[19]

In 2020, the director of the Mirogoj Cemetery informed a politician from Veles that it is impossible to transfer the remains of Brashnarov because they cannot be identified, as he was buried among a large number of people.[20] In July 2023, the council of Veles Municipality unanimously adopted a proposal from The Left party, to have Brashnarov's remains brought to Veles from Croatia.[21]

References

- ^ Му ставивме споменик, не му го најдовме гробот Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ В концентрационния лагер "Голи Оток" завършва трагично своя живот изтъкнатият български патриот Панко Брашнаров от Велес. For more see: Славе Гоцев, Борби на българското население в Македония срещу чуждите аспирации и пропаганда 1878-1945, Университетско издателство "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1991, стр. 190.

- ^ a b Blaže Ristovski, ed. (2009). Makedonska enciklopedija (in Macedonian). MANU. p. 207.

- ^ Енциклопедичен речник за Македония и македонските работи, Цанко Серафимов, Орбел, 2004, стр. 183.

- ^ a b Dimitar Bechev (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia. Scarecrow Press. p. 30. ISBN 0810862956.

- ^ a b c d e f Alexis Heraclides (2021). The Macedonian Question and the Macedonians: A History. Routledge. pp. 92, 100, 158, 183. ISBN 9780367218263.

- ^ a b c d Roumen Dontchev Daskalov; Tchavdar Marinov, eds. (2013). Entangled Histories of the Balkans: Volume One: National Ideologies and Language Policies. BRILL. p. 328. ISBN 900425076X.

- ^ Размисли върху революцията в Европа, Красимир Узунов, Център за изследване на демокрацията, 1992, София, стр. 74.

- ^ Newspaper Makedonsko Delo, Vienna, No. 93-94, June 25, 1929; the original is in Bulgarian.

- ^ Църнушанов, Коста. Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Университетско издателство "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992, стр. 390-391.

- ^ Minchev, Dimitre. Bulgarian Campaign Committees in Macedonia - 1941 (Минчев, Димитър. Българските акционни комитети в Македония - 1941, София 1995, с. 28, 96-97)

- ^ a b Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- ^ Веселин Ангелов (2005). Македонският въпрос в българо-югославските отношения (1944–1952) (in Bulgarian). Sofia: УИ "Св. Климент Охридски. pp. 437–444.

- ^ Heinz Willemsen, The Labour Movement and the National Question: The Communist Party of Yugoslavia in Macedonia in the Inter-War Period, Vol. 33 (2005): Social Movements in Southeast Europe, p. 102.

- ^ a b Corina Dobos, Marius Stan, History of Communism in Europe vol. 1 / 2010: Politics of Memory in Post-communist Europe, Zeta Books, 2010, ISBN 9789731997858, p. 200.

- ^ a b "Посмртните останки на првиот претседавач со АСНОМ и македонски револуционер Панко Брашнаров да бидат вратени од Хрватска во Македонија, односно во родниот Велес". OhridSky (in Macedonian). 4 July 2023.

- ^ Goli Otok: The Island of Death: a Diary in Letters, Venko Markovski, Social Science Monographs, Boulder, 1984, ISBN 0880330554, р. 42.

- ^ Stefan Troebst, Historical Politics and Historical 'Masterpieces' in Macedonia before and after 1991, New Balkan Politics, issue 6, 2003.

- ^ Цочо В. Билярски, Закъснялото осъзнаване на разкаялите се родоотстъпници Павел Шатев и Панко Брашнаров, 24.04.2010, Сите българи заедно.

- ^ "Посмртните останки на Панко Брашнаров, првиот претседавач на АСНОМ, нема да се вратат во родниот Велес од Загреб". Сакам Да Кажам (in Macedonian). 28 July 2020.

- ^ "Велес ќе ги враќа моштите на Панко Брашнаров, по иницијатива на Левица" (in Macedonian). Sloboden Pechat. 4 July 2023.

External links

- Panko Brashnarov's speech at ASNOM's first session (in Macedonian)