Metodija Andonov-Čento

Metodija Andonov-Čento | |

|---|---|

| Методија Андонов-Ченто | |

| |

| Born | 17 August 1902 |

| Died | 24 July 1957 (aged 54) |

| Organization(s) | Yugoslav Partisans (Macedonian Partisans); Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia; Anti-fascist Assembly for the National Liberation of Macedonia |

Metodija Andonov-Čento (Macedonian: Методија Андонов-Ченто; Bulgarian: Методи Андонов-Ченто; 17 August 1902 – 24 July 1957) was a Macedonian politician, partisan leader and the first president of the Anti-Fascist Assembly of the National Liberation of Macedonia and the People's Republic of Macedonia's assembly in the Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia. In the Bulgarian historiography he is often considered a Bulgarian.[1][2][3] During the interwar period, he earned a living as a merchant. After World War II, he was persecuted by the Yugoslav Macedonian authorities for his desire to establish an independent Macedonia. The persona of Čento was a taboo in Yugoslav Macedonia, but it was rehabilitated during the 1990s, after the country gained its independence.

Biography

Early life

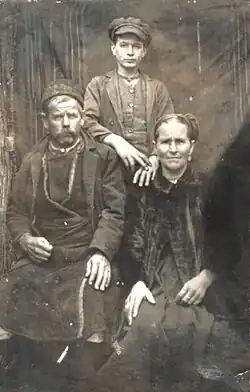

Metodi Andonov was born on 17 August 1902 in Prilep, which was then part of the Manastir Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire.[4] His father originated from Pletvar, while his mother originated from Lenište.[5] After the Balkan Wars in 1913 the area was ceded to Serbia.[6] During the World War I Bulgarian occupation, the authorities were popular enough there.[7] After the war, the area was ceded to the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (later Yugoslavia). As a child, he worked in opium poppy fields and harvested tobacco. During his youth, he was considered to be an excellent gymnast. He graduated from trade school in Prilep and in 1926 he opened a grocery store and provided himself with a decent living. On 25 March 1930, in Novi Sad, he entered into a civil marriage with Vasilka Spirova Pop-Atanasova.[5] Čento underwent such a transformation from pro-Bulgarian to an ethnic Macedonian.[8]

The politicians in Belgrade actually helped to strengthen the developing Macedonian identity by promoting forcible Serbianization during the interwar period.[9] In the 1938 Yugoslav elections, he was elected as a deputy from the United Opposition, but did not become a member of parliament because of a manipulation with the electoral system.[5] His ally was Vladko Macek, leader of the Croatian Peasant Party, who managed to have a Banovina of Croatia created in 1939 through an agreement with the Yugoslav government. In the same year, Čento called for the creation of an unified Banovina of Macedonia, but Macek did not take the claim seriously.[10]

During World War II

He was imprisoned at Velika Kikinda for co-organizing the Ilinden demonstrations in Prilep in 1940. In the same year, he advocated for the introduction of the Macedonian language in school lectures and was therefore imprisoned at Bajina Bašta and sentenced to death by the government of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. On 15 April 1941 he was presented to a firing squad, but was pardoned just prior to being shot during the invasion of Yugoslavia by the Axis Powers.[5] After the capitulation of Yugoslavia, Čento was released from prison and came in contact with the right-wing Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) activists and pro-Bulgarian political forces.[11] His friends attempted to convince him to collaborate with the Bulgarian authorities, but he stated: "I did not fight the Serbs to bring in the Bulgarians, but for the unification of Macedonia." In February 1942, he went to prison, first in Prilep. Afterwards he was transferred to Bitola, then later back to Prilep, then in Skopje, Sofia and Plovdiv, finally being incarcerated at the Bulgarian labor camp Cuculigovo near the Bulgarian-Turkish border.[10]

Upon his release, in September 1943, Čento met Kuzman Josifovski, a member of the General Staff of the Macedonian Partisans who convinced him to join them in the resistance.[5] As a result, on 1 October 1943, Čento went to the German occupation zone of Vardar Macedonia, then part of Albania, where he joined the resistance. Although he was not a member, the Yugoslav communists gave him a position at the supreme headquarters of the Macedonian Partisans because of his popularity among the locals.[12] However, he did not have any previous military experience and his role was purely political. He immediately tried to put Macedonian unification into the Yugoslav communists' agenda, and he managed to get it written in the General Staff Manifesto in October.[10] He was listed as a participant, along with other people from Macedonia, in the second session of Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Yugoslavia (AVNOJ) in November 1943, although he and other Macedonians did not participate.[13] At AVNOJ, Macedonia was recognized as one of the future six republics, which would be incorporated into communist Yugoslavia.[10] Čento also became a member of AVNOJ.[14] In December 1943, Čento was elected as a chairman of the Initiative committee for the organization of the Antifascist Assembly of the National Liberation of Macedonia (ASNOM). In June, Čento along with Emanuel Čučkov and Kiril Petrušev, met with Josip Broz Tito on the island of Vis for consultations due to their activity. The meeting was held on 24 June, with the Macedonian delegation raising the idea of the creation of an United Macedonia after liberation,[5] but the Greeks rejected such a discussion.[10] On 2 August 1944, in the first session of ASNOM, he was elected as president of the presidium of ASNOM, while Panko Brashnarov was elected as vice president.[13] He had also invited pro-Bulgarian activists to the session, such as Yordan Chkatrov.[15] In the second session of ASNOM, on 29–30 December 1944 in Skopje, he was re-elected as president,[12] while the pro-Yugoslav Macedonian communist Lazar Koliševski became his first deputy because the Yugoslav communists were alarmed by Čento's anti-Serbian and irredentist views.[16]

In late February 1945, Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito summoned him, Pavel Shatev, Dimitar Vlahov and Mihailo Apostolski for a meeting to try to dissuade demands for immediate action against Greece, although he also still had his own ambitions regarding northern Greece then. Čento wanted the unification of the entire Macedonian region, which would later become independent and be part of a Balkan Federation.[13] He wanted Macedonia to be independent and unified rather than be subservient to Yugoslavia, but he thought that Yugoslavia would achieve the goal of Macedonian unification.[10] Lazar Koliševski and Svetozar Vukmanović - Tempo disapproved of his stance for independence.[15]

After World War II

The new communist authorities started a policy of implementing the pro-Yugoslav line and took hard measures against the opposition. Čento publicly condemned the killings carried out by the authorities in parliament and sent a protest to the Macedonian Supreme Court. He supported the Skopje soldiers' rebellion when officers from the Gotse Delchev Brigade, mutinied in the garrison stationed in Skopje Fortress, but were suppressed by an armed intervention.[17] Čento opposed the sending of Macedonian Partisans to the Syrmian Front. Čento wanted to send them to Thessaloniki (which he perceived as the historical capital of Macedonia),[16] then abandoned by the Germans, for the purpose of creating a United Macedonia. He also opposed the planned return of Serbian colonists, expelled by the Bulgarians.[5][18] He later joined the Yugoslav Federal Assembly.[15] Additionally, Čento did not agree to the stationing of Yugoslav troops from PR Serbia in Macedonia and proposed creating Macedonia's own telegraph agency. The new government in Macedonia was headed by Koliševski.[16] In mid-April 1945, he became the head of the national assembly, but it was virtually a powerless position.[12] In the same year, he also called for the formation of a separate Macedonian Orthodox Church.[16][13] During the drafting of the 1946 Yugoslav Constitution, he proposed a right for all the constituent republics of Yugoslavia to secede, which was not accepted.[13] Čento was forced to resign from all positions in March 1946.[12][15]

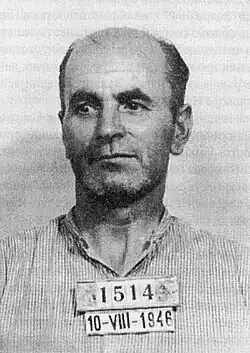

In 1946, he went back to Prilep, where he established contacts with an illegal anti-Yugoslav group, with ideas close to these of the banned Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, which insisted on an independent Macedonia.[10][15] Čento openly called for Macedonia to secede from Yugoslavia and wanted to go to the Paris Peace Conference to advocate for Macedonia's independence. He was arrested in the summer of 1946, after being caught reportedly crossing the border with Greece in order to visit Paris.[19] His arrest resulted in the police allegedly killing 37 pro-Andonov protesters in Resen.[15] In November 1946, Čento was brought before the Macedonian tribunal.[20] The court included the president of the judicial council, Panta Marina, as well as members Lazar Mojsov and Kole Čašule.[21] The fabricated charges against him were of being a Western spy, working against the SR Macedonia as part of SFR Yugoslavia, and being in contact with IMRO terrorists, who supported a pro-Bulgarian independent Macedonia as envisaged by Ivan Mihailov.[14][22][23] During the trial, he was accused of wanting to separate Macedonia from Yugoslavia and unite it with Greece, and that he sought Macedonia to become a protectorate of Britain and the United States. He rejected the first charge but did not deny the second one.[13] In the show trial,[12] he was sentenced to eleven years in prison under forced labor.[24] He was imprisoned in the Idrizovo prison in Skopje.[5] In an internal bulletin of the Bulgarian Communist Party, he was described as a Macedonian militant whose work was denigrated in Skopje.[14] After his imprisonment in November 1946, Koliševski purged real or alleged Čentovites from the Communist Party of Macedonia and the government.[12] His family filed a complaint against his conviction but it was rejected.[5] In 1948, his followers (čentovci) created the organization IMRO-Pravda (IMRO-Truth),[17] which was later dismantled by OZNA.[15] Prison took a toll on his health. He was released conditionally from prison on 4 September 1955, after serving 9 years and 4 months.[5] After his release, he lived in poverty.[10] Čento requested to receive a passport to travel to Switzerland for medical treatment but was declined. He died at his home in Prilep on 24 July 1957 from stomach cancer.[5]

Legacy

His persona was a taboo in Yugoslavia.[25] In 1990, at the request of his son Ilija Andonov, the trial against him was reviewed and on 22 October, the District Court in Skopje overturned the verdict from 1946.[5] In 1991, the Supreme Court of Macedonia annulled the verdict against him from 1946.[11] Before Čento was rehabilitated in the 1990s in Macedonia, he was often described by the Bulgarian communist historiography as a Bulgarian.[26] He is still considered as such in the Bulgarian historiography.[27][28][29][30] Victor Friedman accused Hugh Poulton of implying that Čento was a Bulgarophile.[31]

Čento had a son, Ilija, and a daughter, Marija.[32] Ilija authored a book My Father Metodija Andovo-Čento in 1999. In it, he states that his father identified as a Macedonian and fought for Macedonian unity.[33]

VMRO-DPMNE commemorated him as a martyr for the Macedonian national cause and in their second term, he began to be regarded as the most important Macedonian statesman in modern Macedonian history. In 2010, a five-meter-tall marble statue was erected in his honor in Skopje, depicting him in civilian clothes.[11] On 22 October 2010, the award "Order of the Republic of Macedonia" was posthumously awarded in his honor by Macedonian president Gjorge Ivanov.[34] Because he was the first president of ASNOM's presidium, he has been also described as the "first president of Macedonia".[5]

See also

References

- ^ Rankovich himself opposes Cento's thesis of brotherhood with the Bulgarian people with an address to Pavel Shatev, already Minister of Justice, at a reception with Tito after the first session of the Chamber of Nations: "What are you looking for here, Bulgarian dog?" Cento witnessed this outburst. Returning from Belgrade, he declared to his friends: "Brothers, we are deceived! You know, we are Bulgarians and we thought like Macedonians to cross the bridge. Alas! There is no life with the Serbs". Коста Църнушанов, "Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него", София, 1992 година, Унив. издателство "Св. Климент Охридски, стр 275-282.

- ^ "New Macedonia" under the heading "Against Cento's theses" writes: "We must fight against the Great Bulgarians, who today cannot openly say that Macedonia is a Bulgarian country and that Macedonians are Macedonian Bulgarians"... The most cruel provocation against the political understandings of Metodi Cento, which the YKP qualifies as Bulgarian, was carried out with the killing of 54 prominent Bulgarians in Veles. Славе Гоцев, Борби на българското население в Македония срещу чуждите аспирации и пропаганда 1878-1945, София, 1991 година, Унив. издателство "Св. Климент Охридски, стр. 183-187.

- ^ "After 45 years in the Republic of Macedonia, voices were heard for the rehabilitation of the first Speaker of the National Assembly, Metodi Andonov-Cento, but no longer as a Bulgarian, but as a "Macedonian"... Here are the reasons for the massacre of Metodi Andonov-Cento, one of the most - the bright personalities in the post-war development of Vardar Macedonia, allowed herself in those dark times of the Tito-Kolishev genocide against Bulgaria to express a different from the YKP, essentially Bulgarian-phile position. This is actually what the cational seal in Skopje is trying to hide, making timid attempts to his rehabilitation, but hiding the truth of why he was actually sentenced in such an unscrupulous manner to 11 years in prison." Веселин Ангелов, Премълчани истини: лица, събития и факти от българскарта история 1941-1989, библиотека Сите Българи заедно, Анико, 2005, стр. 42-44.

- ^ Makedonska enciklopedija [Macedonian Encyclopedia]. MANU. 2009. pp. 55–56.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "Методија Андонов Ченто, биографија". Vecer (in Macedonian). 4 February 2021.

- ^ Chris Kostov (2010). Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996. Peter Lang. p. 65. ISBN 978-3034301961.

- ^ Ivo Banac (1984). The National Question in Yugoslavia. Origins, History, Politics. Cornell University Press. p. 318. ISBN 0801494931.

- ^ Коста Църнушанов. Обществено-политическата дейност на Методи Андонов—Ченто (непубликувана статия); сп. Македонски преглед, бр. 3, 2002 г. стр.101-113.

- ^ Bruce Parrott; Karen Dawisha, eds. (1997). Politics, Power and the Struggle for Democracy in South-East Europe. Cambridge University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-521-59733-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Michael Palairet (2016). Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 2, From the Fifteenth Century to the Present). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 195–196, 204–205, 208–209, 294. ISBN 978-1443888493.

- ^ a b c Corina Dobos; Marius Stan, eds. (2010). History of Communism in Europe vol. 1 / 2010: Politics of Memory in Post-communist Europe. Zeta Books. p. 200. ISBN 9789731997858.

- ^ a b c d e f Andrew Rossos (2013). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History. Hoover Press. pp. 197, 224–226. ISBN 9780817948832.

- ^ a b c d e f Alexis Heraclides (2021). The Macedonian Question and the Macedonians: A History. Routledge. pp. 91–94, 183. ISBN 9780367218263.

- ^ a b c Ivo Banac (1988). With Stalin against Tito: Cominformist Splits in Yugoslav Communism. Cornell University Press. p. 203. ISBN 9781501720833.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dimitar Bechev (2019). Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia (2nd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. p. 148. ISBN 978-1538119624.

- ^ a b c d Matjaž Klemenčič; Mitja Zagar (2004). The Former Yugoslavia's Diverse Peoples: A Reference Sourcebook. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 246–247. ISBN 9781576072943.

- ^ a b Stefan Troebst (2007). Das makedonische Jahrhundert: von den Anfängen der nationalrevolutionären Bewegung zum Abkommen von Ohrid 1893-2001. Oldenbourg. pp. 247, 256. ISBN 978-3486580501.

- ^ Блаже Ристовски, Ченто и македонската државност, зборник на трудовите од научниот собир по повод 100-годишнината од раѓањето на Методија Андонов-Ченто, одржан во Скопје на 16 и 17 декември 2002 година, Македонска акедемиjа на науките и уметностите, 2004 година, стр. 17.

- ^ Hugh Poulton (2000). Who are the Macedonians?. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. p. 103. ISBN 1850655340.

- ^ "Macedonia, FYR (Yugoslavia)". Communist Crimes. Estonian Institute of Historical Memory.

The Law for the Protection of Macedonian National Honour was passed in 1945. The act allowed the sentencing of citizens for collaboration, pro-Bulgarian sympathies, and contesting Macedonia's status within Yugoslavia. The latter charge was used to sentence Metodij Andonov-Čento who opposed the authorities' decision to join the federation without reserving the right to a secession and criticised it for not putting enough emphasis on Macedonian culture. For more see: Communist dictatorship in Macedonia. The Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1945-1992).

- ^ "Лустраторите го отвораат досието на Ченто". Kanal 5 (in Macedonian). 29 November 2013.

- ^ Paul Preston, Michael Partridge, Denis Smyth, British Documents on Foreign Affairs reports and Papers from the Foreign Office Confidential Print: Bulgaria, Greece, Roumania, Yugoslavia and Albania, 1948; Europe 1946-1950; University Publications of America, 2002; ISBN 1556557698, p. 50.

- ^ Indiana Slavic Studies, Volume 10; Volume 48; Indiana University publications: Slavic and East European series. Russian and East European series, 1999, p. 75.

- ^ Leslie Benson (2003). Yugoslavia: A Concise History (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 89. ISBN 1403997209.

- ^ Stefan Troebst (2003). "Historical Politics and Historical 'Masterpieces' in Macedonia before and after 1991". New Balkan Politics.

The historians gave up the ideological premises of Tito's and post-Tito's time relatively quickly. Thus, in those parts of the "masterpiece", whose content consisted of those Macedonian political organisations from the time before 1944 and their fight against the forces that wanted to divide Macedonia, they introduced currents and persons who were until then taboos because of the ideology of the Communist Party. This refers to people such as Boris Sarafov, one of the main actors of the Ilinden Uprising in 1903, who was until then excluded from the national pantheon under the suspicion that he was a "Bugarophil"; to Todor Aleksandrov, who from 1919 until his murder in 1924 was president of the Central Committee of VMRO and who brought it onto a pro-world course; to Aleksandrov's anti-communist successor Ivan Mihajlov from 1924 to 1934, and who then became leader of the right wing of VMRO; to the anti-communist leader of the partisans Metodija Antonov – Cento; the national communist dissident Panko Brasnarov; the Bulgarian party official Metodija Shatorov – Sharlo, positioned in Skopje, a city that was then under Bulgarian occupation; and it also referred to the Macedonian national revolutionary Pavel Shatev.

- ^ БКП, Коминтернът и македонският въпрос (1917-1946). Колектив, том 2, 1999, Гл. управление на архивите. Сборник. стр. 1246-1247.

- ^ Добрин Мичев, Македонският въпрос в Българо-югославските отношения (1944-1949). Университетско издателство "Св. Климент Охридски", 1994 г. стр. 77-86.

- ^ Цанко Серафимов, Енциклопедичен речник за Македония и македонските работи, Орбел, 2004, ISBN 9544960708, стр. 184.

- ^ Bernard A. Cook, Andrej Alimov, Europe Since 1945: An Encyclopedia, Vol. 2; Taylor & Francis, 2001, ISBN 0815340583, Macedonia, p. 808.

- ^ Rankovich himself opposes Cento's thesis of brotherhood with the Bulgarian people with an address to Pavel Shatev, already Minister of Justice, at a reception with Tito after the first session of the Chamber of Nations: "What are you looking for here, Bulgarian dog?" Cento witnessed this outburst. Returning from Belgrade, he declared to his friends: "Brothers, we are deceived! You know, we are Bulgarians and we thought like Macedonians to cross the bridge. Alas! There is no life with the Serbs". Коста Църнушанов, "Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него", София, 1992 година, Унив. издателство "Св. Климент Охридски, стр 275-282.

- ^ He is so eager to accept Bulgarian claims that he uncritically reproduces Bulgarian allegations without any indication of their context or veracity ("Who are the Macedonians?", Hugh Poulton 1995: 118 – 119). He even implies that Metodija Andonov - Čento, the first president of the Macedonian republic was a Bulgarophile rather than a Macedonian nationalist . For more see: "Macedonian Historiography, Language, and Identity, in the Context of the Yugoslav Wars of Succession", in Indiana Slavic Studies, Том 10; Том 48, Indiana University publications: Slavic and East European series Russian and East European series, Bloomington. p. 75.

- ^ "Изложба за Ченто во Прилепскиот музеј" [Exhibition for Čento in the Prilep museum]. Sitel. 20 July 2017.

- ^ "Окупација 1941". Мојот татко Методија Андонов-Ченто. Skopje. 1999. p. 106.

Категорично кажав дека не се чуствувам Бугарин, ами Македонец и дека не сум се борел за обединување со Бугарија, туку за обединување на Македонија и за националните права на Македонците.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Metodija Andonov Cento posthumously awarded with the "Order of the Republic of Macedonia". Претседател на Република Македонија. 22 October 2010.

%253B_Flag_of_North_Macedonia_(1991-1992).svg.png)