Palaeocampa

| Palaeocampa Temporal range: Carboniferous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Palaeocampa neotype specimen | |

| |

| Speculative life restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Clade: | Panarthropoda |

| Phylum: | †Lobopodia |

| Class: | †Xenusia |

| Order: | †Protonychophora |

| Family: | †Aysheaiidae |

| Genus: | † Meek & Worthen, 1865 |

| Species: | †P. anthrax

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Palaeocampa anthrax Meek & Worthen, 1865

| |

Palaeocampa (Greek for 'ancient caterpillar') is a genus of aysheaiid lobopodian panarthropods known from the Carboniferous-age Mazon Creek fossil beds and Montceau-les-Mines lagerstätte.[1] The genus contains a single species, Palaeocampa anthrax, which takes its specific name from anthrax (ἄνθραξ), the Greek word for coal, as its fossils were found near coal deposits in Illinois. This genus was first described as a caterpillar, before being redescribed as a fireworm in 2004,[2] and then redescribed again as a lobopodian in 2025. Palaeocampa is extremely unusual for a lobopodian in a variety of ways, being the first and currently only known freshwater lobopodian outside of tardigrades, the first venomous lobopodian, alongside being the only known aysheaiid to possess sclerite armature.

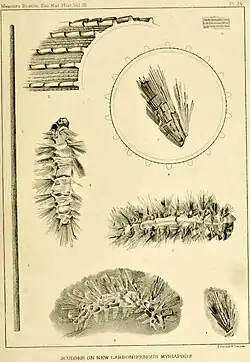

History

Palaeocampa anthrax was first reported from the Mazon Creek deposits of Illinois in 1865 by American paleontologists Fielding Bradford Meek and Amos Henry Worthen. At this point, it was known from only a single specimen discovered by local fossil collector Joseph Evans, which did not preserve the head or legs. The apparent similarity between it and some modern caterpillars led to it being interpreted first as a kind of caterpillar, although this claim was only tentative, as it was not known at the time if lepidopterans existed this far back in the fossil record.[3] Samuel Hubbard Scudder, an entomologist and paleontologist, agreed that there was a resemblance, but not enough to warrant this classification; instead, he assigned it generically to "the class of worms". In 1882, Scudder published a study based on new specimens of Palaeocampa, as the original holotype had been lost in a fire soon after it was described. One specimen preserved the limbs, which allowed Scudder to say confidently that it could not be a caterpillar, which possess three thoracic limbs, a few legless segments, and a number of prolegs, while Palaeocampa possess identical limbs on every segment. Scudder wrote then, that Palaeocampa must belong to the myriapods.[1]

Decades passed with little progress, until French scientists reported the finding of Palaeocampa specimens from the Montceau-les-Mines lagerstätte in 1981. They also suggested Palaeocampa was synonymous with another Mazon Creek worm called Rhaphidiophorus. In 2004, Palaeocampa was redescribed by Fredrik Pleijel, Greg Rouse, and Jean Vannier. They focused on the Montceau-les-Mines specimens, and considered Palaeocampa to be an early fireworm polychaete, again synonymous with Rhapidiophorus.[2] This was based on the two paired sets of spines, which the authors interpreted as chaetae. They determined Palaeocampa to have had a sclerotized proboscis, a pair of antennae, and probably 11 chaetiger segments. This, however, presented a problem for the Montceau-les-Mines lagerstätte. All living members of Amphinomidae (fireworms) are exclusively marine, but all fossil and geological evidence pointed towards Montceau-les-Mines being an intermontane, limnic ecosystem. The authors pointed to other recent discoveries, namely horseshoe crab fossils (Alanops) and a putative hagfish (Myxineidus).[4][5] Alanops was later determined to be a freshwater belinurine species,[4] but Palaeocampa and Myxineidus remained

In 2025, a new team of authors published a comprehensive redescription of Palaeocampa anthrax, based on over 40 specimens from both France and the USA.[1] They demonstrated that Palaeocampa was in fact a lobopodian worm, related to the deep sea Cambrian species Hadranax augustus. This was based on the presence of large, annulated, papillae-bearing lobopodous legs which could not be explained as parapodia, as well as SEM photography of the spines, which had an architecture unlike any other known animal, living or extinct, and incompatiable with an amphinomid polychaete identity. They determined that the presence of a lobopodian within an environment was not sufficient reason to call it marine, when all other evidence pointed to a freshwater ecosystem, as lobopodians from other families had already demonstrated at least a tolerance for brackish waters, and extant families are terrestrial (velvet worms) or exist in a wide variety of environments (tardigrades). The only remaining problematic faunal element then was Myxineidus, however, more recent studies have cast doubt on its hagfish identity, pointing towards a lamprey or stem-lamprey placement.[6][7] What the 2004 study called a proboscis was determined to be a dorsal structure, a sclerotized headshield similar to those found in some other lobopodians (e.g. Collinsovermis).[1] Palaeocampa's lobopodian affinity helps clarify the environmental setting of Montceau-les-Mines, which had until then been the subject of debate.[8][9][10][11]

Description

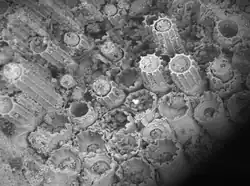

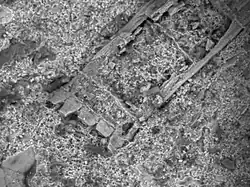

Palaeocampa is a small lobopodian, reaching a maximum of 4 centimetres (1.6 in) in length, not including spines or frontal appendages. It has a head bearing a ridged dorsal sclerite, a large annulated pair of frontal appendages, and a small, secondary pair of appendages just beneath the head. It lacks eyes, and the morphology of its mouth is unknown. The trunk consists of ten segments, each bearing a pair of broad, annulated, lobopodous appendages, approximately equal in length to the width of the trunk, and lacking claws. The entire body and the limbs, including the frontal appendages, are further lined with small, regularly distributed papillae. Above each leg pair are paired sets of dorsolateral and lateral sclerites, or bristles. The body also terminates with an unpaired set of bristles. Each bundle contains a large number of independent bristles, growing from a complex modified basement papillae, the lateral sets being slightly shorter. These sclerites have an architecture unique in the animal kingdom; each spine is straight, highly elongate, and tapered only slightly at the end before expanding back out into a crenellated apex, which Knecht et al. (2025) compared to a rook chess piece. The spine is divided longitudinally by prominent ridges, and between them three smaller ridges. These ridges are serrated, following a sawtooth-like pattern upwardly towards the apex, similar to roof shingles. Internally, the sclerites are septated and hollow, probably with a spongy filling material and a central pore running through the middle. The dorsum of the trunk was thickened compared with the rest of the cuticle, and further reinforced with hundreds of small sclerotized papillae which gave it a pebbly, armoured appearance. These dorsal armour papillae have a small central pore, which is thought to have originally contained a sensory, hair-like seta, similar to the setae-bearing papillae of Aysheaia.[1]

Paleobiology

Palaeocampa is remarkable as the first and currently only known freshwater lobopodian, excluding some tardigrades. Previously, all xenusiid lobopodian fossil have been found in marine deposits, including Palaeocampa's closest relative Hadranax augustus, which is found in Cambrian deep sea deposits. The lost holotype of Palaeocampa comes from an inland, Braidwood biota locality of the Mazon Creek, dominated by plants and populated by various terrestrial and freshwater arthropods, as well as freshwater fish and sharks.[12] The Montceau-les-Mines palaeoenvironment is even further inland, as much as 300 kilometres, an intermontane network of rivers, lakes, and deltas.[9][13] Here, Palaeocampa is found on the same layers as freshwater arthropods like Alanops, and the euthycarcinoids Sottyxerxes and Schramixerxes.[14] It also would have co-existed with freshwater xenacanth sharks, lungfish, temnospondyls, syncarid shrimp, and ostracods.[14][13]

Although chemical defences in lobopodians had been speculated before (such as in the case of the unarmoured Ovatiovermis),[15] Palaeocampa is the only confirmed venomous lobopodian.[1] Exudates found at the tips of the spines were analyzed with FTIR analysis to establish the likely presence of aldehydes, a common molecular component of some invertebrate and plant toxins, such as formic acid and salicylaldehyde. The exact composition of this chemical, and its toxicity, remains out of reach, and it may have served as either a more passive, foul tasting substance secreted from the spines, or as a more active, painful defensive measure expelled when the animal was stressed, such as during a predation attempt. The sclerite bristles of Palaeocampa are unique, and their exact function also remains partly speculative. Disarticulated fossils show that even in the absence of the rest of the body, the sclerites remain mostly intact and embedded in their set, contrasting with the urticating hairs of most caterpillars, tarantulas, and plants, which break away easily on contact.[16] The spines of Palaeocampa also differ in the outward direction of their serrations, as opposed to the inwardly facing hooks more commonly found in urticating hairs.

Gallery

-

Specimen of Palaeocampa from the Mazon Creek fossil beds

Specimen of Palaeocampa from the Mazon Creek fossil beds -

Another specimen of Palaeocampa

Another specimen of Palaeocampa -

SEM photograph of the spines of Palaeocampa, seen emerging from the modified basement papillae

SEM photograph of the spines of Palaeocampa, seen emerging from the modified basement papillae -

SEM photograph of the spine apex of Palaeocampa, showing the crenellated, weakly tapering tip of the spine

SEM photograph of the spine apex of Palaeocampa, showing the crenellated, weakly tapering tip of the spine

References

- ^ a b c d e f Knecht, Richard J.; McCall, Christian R. A.; Tsai, Cheng-Chia; Rabideau Childers, Richard A.; Yu, Nanfang (23 July 2025). "Palaeocampa anthrax, an armored freshwater lobopodian with chemical defenses from the Carboniferous". Communications Biology. 8 (1) 1080. doi:10.1038/s42003-025-08483-0.

- ^ a b Pleijel, Fredrik; Rouse, Greg W.; Vannier, Jean (2004). "Carboniferous fireworms (Amphinomida : Annelida), with a discussion of species taxa in palaeontology". Invertebrate Systematics. 18 (6): 693–700. doi:10.1071/is04003. ISSN 1447-2600.

- ^ Meek, F. B.; Worthen, A. H. (1865). "Notice of Some New Types of Organic Remains, from the Coal Measures of Illinois". Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. 17 (1): 41–48. ISSN 0097-3157. JSTOR 4623982.

- ^ a b Racheboeuf, Patrick R.; Vannier, Jean; Anderson, Lyall I. (2002). "A New Three-Dimensionally Preserved Xiphosuran Chelicerate from the Montceau-Les-Mines Lagerstätte (Carboniferous, France)". Palaeontology. 45 (1): 125–147. Bibcode:2002Palgy..45..125R. doi:10.1111/1475-4983.00230. ISSN 1475-4983.

- ^ Poplin, Cécile; Sotty, Daniel; Janvier, Philippe (2001-03-15). "Un Myxinoı̈de (Craniata, Hyperotreti) dans le Konservat-Lagerstätte Carbonifère supérieur de Montceau-les-Mines (Allier, France)". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences - Series IIA - Earth and Planetary Science. 332 (5): 345–350. Bibcode:2001CRASE.332..345P. doi:10.1016/S1251-8050(01)01537-3. ISSN 1251-8050.

- ^ Germain, Damien; Sanchez, Sophie; Janvier, Philippe; Tafforeau, Paul (2014-04-01). "The presumed hagfish Myxineidus gononorum from the Upper Carboniferous of Montceau-les-Mines (Saône-et-Loire, France): New data obtained by means of Propagation Phase Contrast X-ray Synchrotron Microtomography". Annales de Paléontologie. Lagerstätte de Montceau (Carbonifère) & site de Muse (Permien) - Colloque Autun 2012 / Montceau Lagerstätte (Carboniferous) & Muse locality (Permian) - Colloquium Autun 2012. 100 (2): 131–135. Bibcode:2014AnPal.100..131G. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2013.12.003. ISSN 0753-3969.

- ^ Miyashita, Tetsuto; Coates, Michael I.; Farrar, Robert; Larson, Peter; Manning, Phillip L.; Wogelius, Roy A.; Edwards, Nicholas P.; Anné, Jennifer; Bergmann, Uwe; Palmer, A. Richard; Currie, Philip J. (2019-02-05). "Hagfish from the Cretaceous Tethys Sea and a reconciliation of the morphological–molecular conflict in early vertebrate phylogeny". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (6): 2146–2151. Bibcode:2019PNAS..116.2146M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1814794116. PMC 6369785. PMID 30670644.

- ^ Schultze, Hans-Peter (2009-10-01). "Interpretation of marine and freshwater paleoenvironments in Permo–Carboniferous deposits". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 281 (1): 126–136. Bibcode:2009PPP...281..126S. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2009.07.017. ISSN 0031-0182.

- ^ a b Charbonnier, Sylvain; Vannier, Jean; Galtier, Jean; Perrier, Vincent; Chabard, Dominique; Sotty, Daniel (2008-04-01). "Diversity and Paleoenvironment of the Flora From the Nodules of the Montceau-Les-Mines Biota (Late Carboniferous, France)". PALAIOS. 23 (4): 210–222. Bibcode:2008Palai..23..210C. doi:10.2110/palo.2006.p06-078r. ISSN 0883-1351.

- ^ Garwood, Russell J.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Charbonnier, Sylvain; Chabard, Dominique; Sotty, Daniel; Giribet, Gonzalo (2016). "Carboniferous Onychophora from Montceau-les-Mines, France, and onychophoran terrestrialization". Invertebrate Biology. 135 (3): 179–190. doi:10.1111/ivb.12130. ISSN 1744-7410. PMC 5042098. PMID 27708504.

- ^ Rolfe, W. D. Ian; Schram, Frederick R.; Pacaud, Gilles; Sotty, Daniel; Secretan, Sylvie (1982). "A Remarkable Stephanian Biota from Montceau-les-Mines, France". Journal of Paleontology. 56 (2): 426–428. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1304469.

- ^ Schiffbauer, James; Baird, Gordon C.; Huntley, John Warren; Selly, Tara; Shabica, Charles W.; Laflamme, Marc; Muscente, A. Drew (2025-07-10). "283,821 concretions, how do you measure the Mazon Creek? Assessing the paleoenvironmental and taphonomic nature of the Braidwood and Essex assemblages". Paleobiology: 1–19. doi:10.1017/pab.2025.10045. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ^ a b Heyler, Daniel; Poplin, Cecile M. (1988). "The Fossils of Montceau-les-Mines". Scientific American. 259 (3): 104–111. ISSN 0036-8733.

- ^ a b Racheboeuf, Patrick R.; Vannier, Jean; Schram, Frederick R.; Chabard, Dominique; Sotty, Daniel (2008). "The euthycarcinoid arthropods from Montceau-les-Mines, France: functional morphology and affinities". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of The Royal Society of Edinburgh. 99 (1): 11–25. doi:10.1017/S1755691008006130. ISSN 1755-6929.

- ^ Caron, Jean-Bernard; Aria, Cédric (2017-01-31). "Cambrian suspension-feeding lobopodians and the early radiation of panarthropods". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 17 (1): 29. Bibcode:2017BMCEE..17...29C. doi:10.1186/s12862-016-0858-y. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 5282736. PMID 28137244.

- ^ Battisti, Andrea; Holm, Göran; Fagrell, Bengt; Larsson, Stig (2011-01-07). "Urticating Hairs in Arthropods: Their Nature and Medical Significance". Annual Review of Entomology. 56 (56): 203–220. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-120709-144844. ISSN 0066-4170.