Nikola Karev

Nikola Karev | |

|---|---|

| Никола Карев | |

| |

| President of Krusevo Republic | |

| In office August 3, 1903 – August 13, 1903 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | November 23, 1877 Kırşova, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | April 27, 1905 (aged 27) Near Rayçani, Ottoman Empire |

| Profession | Teacher |

Nikola Yanakiev Karev (Bulgarian: Никола Янакиев Карев; Macedonian: Никола Јанакиев Карев, romanized: Nikola Janakiev Karev; November 23, 1877 – April 27, 1905) was a Macedonian Bulgarian socialist revolutionary of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO). He was also a teacher in the Bulgarian Exarchate school system in his native area,[1][2][3] and a member of the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party.[4] During the Ilinden Uprising he headed the short-lived Kruševo Republic.[5][6][7][8] He is considered a national hero in North Macedonia and Bulgaria.[9][10]

Biography

Early years

Karev completed his early education at the Bulgarian Exarchist school in Kruševo and in 1893 moved to Sofia, the capital of Principality of Bulgaria, where he worked as a carpenter for the socialist Vasil Glavinov. Karev joined the Socialist group led by Glavinov, and through him, made acquaintance of Dimitar Blagoev and other socialists, and became a member of the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party. From 1896 he participated in the Macedonian-Adrianople Social Democratic Group, created as part of the Bulgarian Workers' Social-Democrat Party.[11] In 1898 Karev went back to Ottoman Macedonia and graduated from the Exarchist gymnasium in Bitola. From 1900 he worked as a schoolmaster in the Exarchist schools in the village of Gorno Divjaci and in his native Kruševo.[12][13][10]

Political and revolutionary activity

The first Conference of Macedonian Socialists was held on June 3, 1900, near Kruševo, where they defined the core aspects of the potential creation of a separate Macedonian Republic, as a cantonized state, part of a future Balkan Socialist Federation, as a multinational polity offering equal rights to all its citizens.[14] They maintained the slogan "Macedonia for the Macedonians", using Macedonian people as an umbrella term covering Bulgarians, Turks, Greeks, Aromanians, Albanians, Jews, Serbs, ethnic Macedonians, etc., living in harmony in an independent state.[15][10] In this period Karev joined the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization and became a leader of a regional armed band (cheta).[16]

On the eve of the Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising, in May 1903, he was interviewed in Bitola by the correspondent of the Greek daily Akropolis Stamatis Stamatiou. In the interview, Karev expressed his position of a radical leftist.[17] Stamatiou described him as a Bulgarized Macedonian.[18][note 1] Per Stamatiou, Karev presented himself as a voulgarofron, (i.e. Bulgarophile),[19] and replied he was a Macedonian.[note 2][18] In response to an ironic question by Stamatiou, Karev also claimed to be a "direct descendant of Alexander the Great", but added that "history says he was a Greek".[note 3] Furthemore, he explained that IMRO was not Bulgarian and it just seemed like that because only Bulgaria appeared eager to help them.[18] He also pointed out that Bulgaria's expectation to annex the region was miscalculated,[20] and that the revolutionaries would accept anyone's help in order to attain their goal.[18] When asked what the revolutionaries wanted for Macedonia, Karev explained their plans to create a republic in the model of Switzerland, providing autonomy and democracy for its different "races".[17]

During the Ilinden Uprising of August 1903, after Kruševo was captured by the rebels, they proclaimed the Kruševo Republic and he became the president of its provisional government.[21] Karev allegedly authored the Kruševo Manifesto,[4][22][23] which called upon the local Muslim population to join forces with the Christians in the struggle for an independent Macedonia.[24] Amongst the various ethno-religious groups (millets) in Kruševo a Republican Council was elected with 60 members – 20 representatives from each one: Bulgarian Exarchists, Aromanians and Greeks (Aromanian and Albanian Greek Patriarchists or Grecomans).[7][25][23] The Council also elected an executive body – the Provisional Government, with six members (2 from each mentioned group). Though, an identity problem arose, Karev allegedly called all the members of the local Council "brother Bulgarians", while the IMRO insurgents flew Bulgarian flags, killed several Greek Patriarchists, accused of being Ottoman spies, and subsequently assaulted the local Turk and Albanian Muslims.[26] Karev himself tried to minimize the attacks on the Muslims and prevent the insurgents from looting indiscriminately.[27] On 12 August by the orders of the General Staff of the uprising, he retreated with most of the insurgents in the hills before the Ottoman troops encirclement.[23] Lasting only ten days, the Kruševo Republic was crushed by the Ottoman forces after some intense fighting.

After Ilinden

After the uprising Karev went back to Bulgaria and became a political activist of the newly founded Marxist Bulgarian Social Democratic Workers' Party (Narrow Socialists). In 1904, Karev made a legal attempt to return to Macedonia, taking advantage of the Bulgarian-Ottoman Amnesty Agreement for the participants in the Ilinden Uprising. He sent several applications for amnesty to Istanbul through the cabinet of the Bulgarian Prime Minister Racho Petrov. The applications were received by the Ottoman Amnesty Commission but remained unanswered, despite the intercession of the Bulgarian diplomatic agent in Istanbul, Grigor Nachovich.[28]

On March 16, 1905, the chetas of Nikola Karev and Petar Atsev passed through the Kyustendil checkpoint of the IMARO and entered Ottoman territory. Soon after, Karev's detachment was discovered by Ottoman soldiers, and in the ensuing battle he was killed near the village of Rajčani, together with his comrades Dimitar Gyurchev and Krastyo Naumov.[29][30]

Family

His two brothers, Petar and Georgi also participated in IMRO.[31] During World War II, in the Bulgarian-annexed Vardar Macedonia, Georgi became briefly a Mayor of Kruševo in 1941.[32] In late 1944, after SR Macedonia's authorities came to power he was arrested and trialed as a Bulgarian fascists' collaborator. He served his sentence in the Idrizovo prison and died there in 1949 or 1951, allegedly poisoned.[33] His son Mihail, was also imprisoned in 1959 for a year and half for "activities against the people and the state", while he claimed that he was imprisoned for demanding a truly autonomous Macedonia without communist control, but under an international protectorate. According to a later testimony of Mihail, this was the reason he and his father Georgi were imprisoned. Bulgarophilia was used as a rhetorical strategy by the communist regime against opponents. Furthermore, as Mihail pointed out, this was used against his dead uncle as well, of whom the communist leaders envied and wanted to devalue his legacy by denouncing him as Bulgarian.[23] The other brother, Petar, was sentenced to imprisonment on the same charges,[34] dying reportedly in 1951 in Idrizovo prison.[35][36] According to other reports, after serving his sentence, he was released and died in 1962.[37]

Legacy

After World War II, the Kruševo Republic was promulgated as a historical predecessor of the new Socialist Republic of Macedonia by the Macedonian historiography. The focal point in the establishment of socialist continuity with the events of 1903 was Karev because of his socialist views.[38][39] His name was part of the anthem of SR Macedonia: "Today over Macedonia." However, later it was removed without an official explanation.[40][41] On August 2, 1948, a plaque was unveiled on his house, and a statue was erected in 1952. In 1953, on the 50th anniversary of the Ilinden Uprising, Karev's remains were transferred to his hometown Kruševo from the village of Rajčani where he was buried in 1905.[42] However, there was no reinterment and his remains were placed in the storage of the town's historical museum. According to anthropologist Keith Brown, this decision may have been result of the suspicion of Bulgarian baggage in Karev's legacy by the communist leaders in this period, despite the efforts to commemorate him.[43] Nevetheless, by the 1960s his name was firmly acclaimed. In 1969 the Yugoslav leader Josip Broz Tito paid tribute by laying a wreath on Karev's statue. In April 1990, his remains were ceremonially transferred to a sarcophagus placed in the Ilinden Uprising memorial, in the presence of Karev's family and representatives of the government.[23]

In North Macedonia, he is regarded as an ethnic Macedonian.[20] In 2008, a large bronze equestrian monument of Nikola Karev was placed in front of Parliament Building in Skopje, cast by the Ferdinando Marinelli Artistic Foundry of Florence, Italy.[44]

Gallery

-

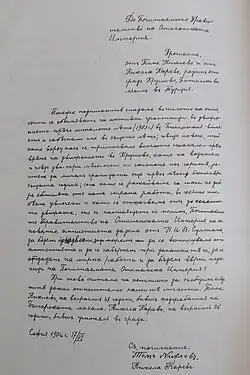

Autobiography of Nikola's brother Georgi Karev from 1943, where he claims hе was born in a Bulgarian family (in Bulgarian).

Autobiography of Nikola's brother Georgi Karev from 1943, where he claims hе was born in a Bulgarian family (in Bulgarian). -

Monument of Karev near the Makedonium memorial complex, uncovered on the 50th year anniversary of the Ilinden uprising on August 2, 1953

-

.jpg) Monument of Nikola Karev in front of the Macedonian Parliament in Skopje.

Monument of Nikola Karev in front of the Macedonian Parliament in Skopje.

Notes

- ^ Per Chavdar Marinov at the eve of the 20th century the treatment of the Greek society towards the Macedonian Slavs was changed. Until then they were accepted as Bulgarians, but after the aggravation of the Bulgarian-Greek relations on the Macedonian question, it was proved that the Macedonian Slavs were in fact Greeks, and that their language was not Bulgarian. The name Bulgarians also was taken out of use for them. At the time, the Greek researchers claimed that the Slavophones were simply Slavicized Greeks. This idea suggests that the Macedonian Slavs had lost their original Greek language and culture over the centuries, and it was time to them to return to their Hellenic roots. For the Greek audience the Macedonian Slavs were in historical aspect Ancient Macedonians (i.e. Greeks), not related to the Bulgarians. They were labelled as Bulgarian-speaking Greeks and even Slavic-speaking "Macedonians". For more see: Tchavdar Marinov, "Famous Macedonia, the Land of Alexander: Macedonian Identity at the Crossroads of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian Nationalism", In: Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One, pp: 290–291.

- ^ "Per Eleftheria Vambakovska, the interview, contains contradictory claims and actually begins with an illogical claim. Karev asserts he is a Bulgarian-minded ("Bulgarophron"), and on the first question of the reporter: "Are you a Macedonian", he answers with "yes". The reporter and the Greek audience then, regarded Macedonia as a Greek territory and hence the people living here, according to them, must be Greeks and descendants of Alexander the Great. That's why he was so persistently trying to persuade Karev, that he is Macedonian, i.e. Greek. And if he was not a Greek, then he is "Voulgarophron", "Bulgarized Macedonian", etc. Otherwise, it is easy to see that the interview was adopted for the Greek readers in 1903. The interview begins with a question "are you a Macedonian"? that means Karev's ethnic origin was more important for the interviewer – whether he is a "Macedonian", which to the Greeks was a synonymous of a "Greek". Otherwise, to the Greeks "Bulgarian-minded" was not so important – the conviction is acquirable and it can by changed. "Bulgarophron", literally translated would mean – a man who thinks like all the Bulgarians. Today the Greeks have a similar term – ethnicophronos, which has similar meaning, namely – a man who thinks on his own nation – nationalist, a Greek who thinks about Greece. Today the Macedonians in Aegean Macedonia (Greece) call their countrymen who became hellenized, i.e. Greeks – ethnicophronos. The journalist, and not only he, regards Macedonia as a Greek territory and hence the people living here, according to them, must be Greeks, descendants of Alexander the Great. That's why he is so persistently trying to persuade Karev, that he is Greek. And if he is not a Greek, then he is "Bulgarophonos", "Bulgarian Macedonian", etc. Otherwise, it is easy to see that the interview is "slightly tuned", adapted for the Greek readers in 1903." For more see: Утрински Весник, Сабота, July 22, 2000 Архивски Број 329. По откривањето на интервјуто на Никола Карев за 'Акрополис' во 1903. Одважноста на претседателот на Крушевската Република. Елефтерија Вамбаковска, Глигор Стојковски; Академик Катарџиев, Иван. Верувам во националниот имунитет на македонецот, интервју за списание "Форум", 22 jули 2000, број 329.

- ^ Tassos Kostopoulos compares Stamatiou's distrust towards Karev's self-presentation with the profession of a "purely Macedonian consciousness" of the Bulgarian Army colonel Anastas Yankov during his short passage through Greece on his way back from Macedonia to Bulgaria in December 1902, after the failed Gorna Dzhumaya Uprising, which, contrary to Karev's, was received cordially by Greek nationalists and taken at face value even by the most Slavophobe Greek newspapers. See Tassos Kostopoulos, Faire la police dans un pays etranger, pp. 5-6, n. 21.. Per Tchavdar Marinov the manifesto issued by Anastas Yankov during the Gorna Dzhumaya Uprising promulgated only a specific “local Macedonian” patriotism, a phenomenon that was described at the beginning of the twentieth century by foreign observers such as Henry Noel Brailsford and Allen Upward. They likewise noted the legend that Alexander the Great and Aristotle were “Bulgarians.” Obviously, by the late Ottoman period, the ancient glory of the region was exploited for self-legitimation by groups with different loyalties—Greek as well as Bulgarian. At that time the anarchist Pavel Shatev described the first vestiges of the process of an ethno-national differentiation between Bulgarian and Macedonian, while some people he met felt “only Bulgarians”, but others despite being Bulgarians "by nationality", felt themselves Macedonians above all. It was generating a new identity that, during that period, was still not necessarily exclusive vis-à-vis Greek or Bulgarian national belonging. Marinov claims that people as Yankov, although Bulgarians by national identification and Macedonian supranationalist by political conviction, began to promote rarely the prognostics of some different ethnicity, which after the First World War were transformed into definitive Macedonian nationalism. For more see: Tchavdar Marinov, "Famous Macedonia, the Land of Alexander: Macedonian Identity at the Crossroads of Greek, Bulgarian and Serbian Nationalism", In: Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume One, pp: 293–294; 304.

References

- ^ Julian Allan Brooks (December 2005). "'Shoot the Teacher!' Education and the Roots of the Macedonian Struggle"" (PDF). Department of History – Simon Fraser University. pp. 136–137.

The expanding Exarchate school system was ideally suited to IMRO's goals. It gave them the means to spread their message and recruit new members. It also served as a ready-made infrastructure which IMRO members could exploit while ostensibly labouring as humble teachers.

- ^ Julian Brooks (2015). "The Education Race for Macedonia, 1878—1903". Journal of Modern Hellenism. 31: 23–58.

The Exarchate schools attracted thousands of students in Macedonia for several reasons. First, they drew Slavic-speaking students away from Greek schools by offering the Slavs education in a language that was close, if not identical, to their own, and by establishing schools in villages where schools had not existed hitherto. Second, boarding schools in centers like Skopje, Kastoria, Bitola, and Thessaloniki gave promising students a chance to leave their villages and continue their education; some students could even look forward to scholarships to study in Sofia. Third, in the 1890s, Exarchate teachers were increasingly likely to be native Macedonians who had come up through the school system and had received further education in Sofia and beyond. Finally, another important "pull" factor for the Exarchate schools was the fact that they were free, which encouraged many parents to forgo the prestige of a Greek education in order to save money... In Macedonia, the education race produced the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), which organized and carried out the Ilinden Uprising of 1903. Most of IMRO's founders and principal organizers were graduates of the Bulgarian Exarchate schools in Macedonia, who had become teachers and inspectors in the same system that had educated them. Frustrated with the pace of change, they organized and networked to develop their movement throughout the Bulgarian school system that employed them. The Exarchate schools were an ideal forum in which to propagate their cause, and the leading members were able to circulate to different posts, to spread the word, and to build up supplies and stores for the anticipated uprising. As it became more powerful, IMRO was able to impress upon the Exarchate its wishes for teacher and inspector appointments in Macedonia.

- ^ Bulgarians, inspired by the rise of nationalism, began to set up their own national churches and schools independently of the Patriarchate of Constantinople. In 1870 they were also allowed to establish an Exarchate, which, within the framework of the millet system, became more than a mere religious institution, coming to represent the Orthodox Bulgarians as a separate nation in the Ottoman Empire. As such, the Bulgarian Exarchate established a network of national schools where it took care of both religious and secular education of the Orthodox Bulgarians under its jurisdiction. For more see: Maria Schnitter, Daniela Kalkandjieva, Teaching Religion in Bulgarian Schools in Adam Seligman (ed.) Religious Education and the Challenge of Pluralism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 70-95.

- ^ a b Aleksandar Pavković; Christopher Kelen (2016). "Chapter 6 – A Fight for Rights: Macedonia 1941". Anthems and the Making of Nation States: Identity and Nationalism in the Balkans. I.B. Tauris. p. 168. ISBN 9781784531263.

- ^ Marco Dogo; Stefano Bianchini, eds. (1998). The Balkans: National Identities in a Historical Perspective. Longo. p. 121. ISBN 8880631764.

In liberated Krushevo, the rebel government established itself as a republic, to be remembered in historiography and collective memory as the Krushevo Republic. The Republic, the first of its kind on the Balkans, represented a model of statehood for all of Macedonia and an expression of the revolutionary ideology of TMORO: the "Macedonian Independent Republic" would provide real freedom for the Macedonian people, including minorities, independence, economic, political, cultural and social development

- ^ John Paul Newman; Balázs Apor, eds. (2021). Balkan Legacies: The Long Shadow of Conflict and Ideological Experiment in Southeastern Europe. Purdue University Press. p. 268. ISBN 1612496695.

The Ilinden Uprising against the Turkish rule in 1903 was one of the most important events in the history of Macedonian people. During the uprising, in the small town of Krusevo the first republic in the Balkans was created. Even though it lasted just for ten days, it had a great impact on the Macedonian liberation movement, especially during World War II and the creation of the Macedonian state as a part of the Yugoslav federation in 1944, as well as on the international community, which was alerted for the existence of the Macedonian people.

- ^ a b Stoyan Pribichevich (1982). Macedonia, Its People and History. Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. 128–129. ISBN 0271003154.

- ^ Lauren S. Bahr, ed. (1997). Collier's Encyclopedia: With Bibliography and Index. Collier's. p. 160. LCCN 96084127.

- ^ Nikola Karev was a Bulgarian revolutionary, narrow socialist and teacher. He was an activist of the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan liberation movement and a participant in the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie uprising. For more: Пелтеков, Александър Г. Революционни дейци от Македония и Одринско. Второ допълнено издание. София, Орбел, 2014. ISBN 9789544961022, стр. 210-211.

- ^ a b c Bechev, Dimitar (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia. Scarecrow Press. pp. lviii, 114. ISBN 9780810862951.

- ^ The politics of terror: the Macedonian liberation movements, 1893–1903, Duncan M. Perry, Duke University Press, 1988, ISBN 0-8223-0813-4, p. 172.

- ^ From 1900 to 1903, Karev was a teacher at the Bulgarian schools in the village of Gorno Divjaci and in his native Kruševo. Билярски, Цочо. „Никола Карев, Председателят на Крушовската република“, Сите Българи заедно. Jan 31, 2012.

- ^ Николов, Борис Й. Вътрешна Македоно-одринска революционна организация. Войводи и ръководители (1893–1934). Биографично-библиографски справочник, София 2001, с. 74

- ^ We, the people: politics of national peculiarity in Southeastern Europe, Diana Mishkova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 963-9776-28-9, p. 122.

- ^ Benjamin Lieberman (2013). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 56. ISBN 144223038X.

- ^ Антони Гиза, Балканските държави и Македонския въпрос (превод от полски - Димитър Димитров, Македонски Научен Институт София, 2001) стр. 35.

- ^ a b Michalopoulos, Georgios (2013). Political parties, irredentism and the Foreign Ministry: Greece and Macedonia, 1878-1910 [PhD thesis]. Oxford University, pp. 163-164.

- ^ a b c d Stamatis Stamatiou, From Bitola. Interview with a member of the Committee.

- ^ The term means someone with pro-Bulgarian convictions. For its English translation see Philip Carabott, "The Politics of Constructing the Ethnic 'Other': The Greek State and Its Slav-speaking Citizens, ca. 1912 - ca. 1949", p. 151, Anastasia Karakasidou, "The Slavo-Macedonian 'non-minority'", p. 129, 153, n. 26 and Nada Boshkovska, Yugoslavia and Macedonia Before Tito: Between Repression and Integration (London/New York: I. B. Tauris, 2017), p. 8.

- ^ a b Седумдесет години Институт за историја / Седумдесет години македонска историографија [Seventy Years Institute of History / Seventy Years of Macedonian Historiography]. ИНИ, Филозофски факултет. 2017. pp. 75–76.

Во интервјуто Карев нагласил дека е Македонец, а не Бугарин и дека целта на борбата е добивање на автономија на Македонија, нагласувајќи дека Бугарија си прави лоши сметки доколку мисли дека може да ја претвори Македонија во нејзина провинција.

[In the interview, Karev emphasized that he was Macedonian, not Bulgarian, and that the goal of the struggle was to gain autonomy for Macedonia, emphasizing that Bulgaria was doing itself a disservice if it thought it could turn Macedonia into its province.] - ^ Two Krusevo natives were centrally involved in the action. Nikola Karev, from the community known as Bulgars, was the local representative to the central committee of the organization and was the military commander of the insurgent forces... Fieldwork Dilemmas: Anthropologists in Postsocialist States, Hermine G. De Soto, Nora Dudwick, Univ of Wisconsin Press, 2000, ISBN 978-0-299-16374-7, p. 37.

- ^ Dimitar Bechev Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia, Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, ISBN 1538119625, p. 166.

- ^ a b c d e Brown, Keith (2003). The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. Princeton University Press. pp. 81–82, 141–142, 189–193, 230. ISBN 0-691-09995-2.

- ^ Loring M. Danforth (1997). The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0691043566.

On August 2, 1903, VMRO led the Macedonian peasantry in the Ilinden Uprising, named after the festival of the Prophet Elijah on which it began. This was one of the greatest events in the history of the Macedonian people. The high point of the Ilinden Revolution was the establishment of the Krushevo Republic in the town of Krushevo in central Macedonia. The leaders of the Krushevo Republic called on all the people of Macedonia, Moslems and Christians alike, to join them in fighting for an independent Macedonia.

- ^ "Беше наполно прав и Мисирков во своjата фундаментална критика за Востанието и неговите раководители. Неговите укажуваньа се покажаа наполно точни во послешната практика. На пр., во ослободеното Крушево се формира градска управа составена од "Бугари", Власи и Гркомани, па во зачуваните писмени акти не фигурираат токму Македонци(!)..." Блаже Ристовски, "Столетиjа на македонската свест", Скопје, Култура, 2001, стр. 458.

- ^ Michael Palairet (2016). Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 2). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 149. ISBN 1443888494.

- ^ Keith Brown, Loyal Unto Death: Trust and Terror in Revolutionary Macedonia, Indiana University Press, 2013, ISBN 9780253008473, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Цочо Билярски, Никола Карев — председателят на Крушевската република, публикувано в Сите българи заедно на 31.01.2012.

- ^ Николов, Борис Й. Вътрешна македоно-одринска революционна организация: Войводи и ръководители (1893-1934): Биографично-библиографски справочник. София, Издателство „Звезди“, 2001. ISBN 954-9514-28-5, с. 74.

- ^ Пелтеков, Александър. Революционни дейци от Македония и Одринско. Второ допълнено издание. София, Орбел, 2014. ISBN 9789544961022. стр. 242; 324.

- ^ Македонска енциклопедија, том I. Скопје, Македонска академија на науките и уметностите, 2009. ISBN 978-608-203-023-4. с. 677.

- ^ Илюстрация Илинден, ноември 1941, година 13, книга 9 (129), стр. 13.

- ^ Ристески, Стојан. Судени за Македонија (1945–1985), Полар, Охрид, 1995, стр.311–324. Archived April 7, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Коста Църнушанов, Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Унив. изд. "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992, стр. 336, 478.

- ^ Пелтеков, Александър Г. Революционни дейци от Македония и Одринско. Второ допълнено издание. София, Орбел, 2014. ISBN 9789544961022. с. 211.

- ^ Македонска енциклопедија, том I. Скопје, Македонска академија на науките и уметностите, 2009. ISBN 978-608-203-023-4. с. 211.

- ^ Никола Карев: „Петруш, ние од Турчинот ќе се ослободиме, ама потоа кој знае кој ќе нѐ заземе?!“ Факултети - 03.08.2018

- ^ "Macedonian revolutionary heroes are carefully treated. In addition to appropriating the historical legacies of the key founders of the original IMRO-Goce Delcev, Damian Gruev and Pere Tosev-Macedonian historians play up lesser figures, who might have given the slightest indication of "socialist" inclination or who were not openly Bulgarophiles. Thus there is glorification of men like Jane Sandanski, Dimo Hadji-Dimov, Petar Poparsov and Nikola Karev, who, because they defected from the IMRO or lost out in internecine organizational fights, have long been forgotten by chroniclers of the IMRO" For more see: Stephen E. Palmer, Robert R. King, Yugoslav communism and the Macedonian question, Archon Books, 1971, ISBN 0208008217, Chapter 9: The encouragement of Macedonian culture.

- ^ "After 1945, in ex-Serbian Macedonia, the authorities rehabilitated the idea of a separate Macedonian language, identity and consciousness, sponsoring the creation of a separate Macedonian Church. At the same time, official history rehabilitated only certain VMRO-era revolutionaries, like Goce Delcev, Nikola Karev and Dame Gruev, who they deemed deserving because they were not associated with the idea of union of Macedonia with Bulgaria. Meanwhile, most emphasis was placed on celebrating the joint Yugoslav history of the World War II Communist struggle. Other VMRO figures, like Todor Aleksandrov or Ivan Mihajlov remained blacklisted owing to their strong pro-Bulgarian stands. Historians today agree that the truth was not so black-and-white. Per Prof. Todor Cepreganov: Almost all Macedonian revolutionaries from that era at some point of their life took pro-Bulgarian stands or pronounced themselves as Bulgarians – this is not disputed. However, you have to have in perspective the non-existence of a Macedonian state [at the time] and the strong influences of neighbouring countries. Many people were then educated in Bulgarian schools,” he adds." See: Sinisa Jakov Marusic, New Statue Awakens Past Quarrels in Macedonia, in Balkan Transitional Justice - BIRN, July 13, 2012.

- ^ Pål Kolstø, Strategies of Symbolic Nation-building in South Eastern Europe, Routledge, 2016, ISBN 1317049365, p. 188.

- ^ Блаже Ристовски (уредник) „Рациновите македонски народно-ослободителни песни“, „Матица македонска“, Скопје, 1993, 40 стр.

- ^ "Првпат доаѓам на местото на погибијата на дедо ми Никола Карев" (in Macedonian). Dnevnik. April 29, 2015. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ Keith Brown (2018). The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. Princeton University Press. p. 192. ISBN 0691188432.

It appears that, despite their best efforts, the new régime had not quite made his legacy entirely their own, and Bulgarian claims on his legacy continued to be lodged. The phenomenon noted by Miše Karev, that Nikola carried Bulgarian baggage at some points in Yugoslav history, is confirmed by others in the town. They do not, however, necessarily link the origin of this version of Nikola Karev's career to a policy of disinformation by Koliševski and his associates. Some people recall their grandparents' unshakable conviction that in 1903 Karev addressed himself to his "brother Bulgarians" as recorded in the account given by Nikolaos Ballas. Others in the town comment critically on Karev's decision to abandon the town before the Ottoman forces arrived. It seemed to fit with a template of action promoted by those Macedonian leaders who aimed to provoke Turkish outrages against the Christian population and thus compel foreign intervention, either from Bulgaria or from the Great Powers. The policy was explicitly endorsed by Boris Sarafov, who was consistently cast by Macedonian historiography as under the sway of the Bulgarian court, as described in the chapter 7. Karev's own close links to Sofia—he spent extended periods there before and after the Uprising—gave further grist to the rumor mill that associated him closely with pro-Bulgarian forces. Miše's commentary on Yugoslav suspicion of Karev therefore seems to have some basis, at least for the period of the 1950s.

- ^ "Ќе се издигне седумметарскиот споменик на Никола Карев" (in Macedonian). Skopje: Večer. September 13, 2011. Archived from the original on September 13, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

Bibliographies

- Пандев, К. "Устави и правилници на ВМОРО преди Илинденско-Преображенското въстание", Исторически преглед, 1969, кн. I, стр. 68–80. (in Bulgarian)

- Пандев, К. "Устави и правилници на ВМОРО преди Илинденско-Преображенското въстание", Извeстия на Института за история, т. 21, 1970, стр. 250–257. (in Bulgarian)

- Битоски, Крсте, сп. "Македонско Време", Скопје – март 1997, quoting: Quoting: Public Record Office – Foreign Office 78/4951 Turkey (Bulgaria), From Elliot, 1898, Устав на ТМОРО. S. 1. published in Документи за борбата на македонскиот народ за самостојност и за национална држава, Скопје, Универзитет "Кирил и Методиј": Факултет за филозофско-историски науки, 1981, pp 331 – 333. (in Macedonian)

- Hugh Pouton Who Are the Macedonians?, C. Hurst & Co, 2000. p. 53. ISBN 1-85065-534-0

- Fikret Adanir, Die Makedonische Frage: ihre entestehung und etwicklung bis 1908., Wiessbaden 1979, p. 112.

- Duncan Perry The Politics of Terror: The Macedonian Liberation Movements, 1893–1903 , Durham, Duke University Press, 1988. pp. 40–41, 210 n. 10.

- Keith Brown,The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2003.