Kruševo Republic

Kruševo Republic Крушевска Република Republica di Crushuva | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1903 | |||||||||

Flag | |||||||||

| Motto: "Свобода или смърть" (Bulgarian) "Freedom or Death" | |||||||||

| Status | Unrecognized rebel state | ||||||||

| Capital | Kruševo | ||||||||

| Government | Provisional[1] | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1903 | Nikola Karev | ||||||||

| Chairman of the Provisional Government | |||||||||

• 1903 | Dinu Vangel | ||||||||

| Historical era | Ilinden–Preobrazhenie Uprising | ||||||||

• Established | 3 August 1903 | ||||||||

• Disestablished | 13 August 1903 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | North Macedonia | ||||||||

The Kruševo Republic (Bulgarian and Macedonian: Крушевска Република, Kruševska Republika; Aromanian: Republica di Crushuva)[2] was a short-lived political entity, proclaimed in 1903 by rebels from the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO) in Kruševo during the anti-Ottoman Ilinden Uprising.[3] According to Bulgarian and Macedonian historical narratives, in the town, which was inhabited by different Christian populations, an ephemeral "republic" with a temporary revolutionary government was proclaimed.[4] It is viewed as a historical predecessor in North Macedonia.[5][6][7][8]

History

In the early 20th century, Kruševo was mainly inhabited by Slavic Macedonian, Aromanian and Orthodox Albanian population.[7] As a result of the national and religious propaganda the population was ethnoreligiously split on Bulgarian Exarchists and Greek Patriarchists, the latter constituted the largest ethno-religious community.[9][10]

On 3 August 1903, IMRO insurgents captured the town of Kruševo in the Manastir Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (present-day North Macedonia), After the General Staff of the Uprising headed by Dame Gruev and Boris Sarafov entered the city on 4 August, the Krusevo Republic was proclaimed in a speech by Nikola Karev who was elected as president.[7][11][12][13][14] He was a strong socialist and member of the Macedonian-Adrianople Social Democratic Group, favouring alliances with ordinary Muslims against the Sultanate, as well as supporting the idea of a Macedonian republic inside a Balkan Federation and opposing the territorial aspirations of the neighbouring Balkan countries over the region.[15][16]

Amongst the various ethnoreligious groups (millets) in Kruševo, a Republican Council was elected with 60 members – 20 representatives from three groups: Aromanians, Macedono-Bulgarians and Greek self-identifying (Grecoman) Slavic Macedonians, Aromanians and Albanians.[7][17][18][19][20] The Council also elected an executive body – the Provisional Government – with six members (2 from each mentioned group),[21] whose duty was to promote law and order and manage supplies, finances, and medical care. The presumable "Kruševo Manifesto" was published in the first days after the proclamation.[22][23] Written by Nikola Kirov, it outlined the goals of the uprising, calling upon the Muslim population and the Christians alike to join forces with the provisional government in the struggle against Ottoman tyranny, to attain freedom and independence for Macedonia.[24][25][26][27] Kirov was also a leftist like Karev and a member of the Bulgarian Workers' Social Democratic Party.[28] However, Karev allegedly called all the members of the local Council "brother Bulgarians", while the IMRO insurgents flew Bulgarian flags, killed five Greek Patriarchists accused of being Ottoman spies, and subsequently assaulted the local Turk and Albanian Muslims.[29][30][31] Greek sources witness that the insurgents were aggressive or provocative towards the Patriarchist population.[32] Karev attempted to reduce attacks over the Muslim population and prevent the plundering from insurgents and their supporters.[33] He also attended a Greek church service in a gesture of tolerance and unity.[34] However, except for Exarchist Aromanians,[35] who were Bulgarophiles,[36][37] (as Pitu Guli and his family), most members of the other ethnoreligious communities dismissed the IMRO as pro-Bulgarian.[38][39]

Initially surprised by the uprising, the Ottoman government took extraordinary military measures to suppress it. Heading from Prilep, led by Bahtiyar Paşa, a force of 15,000 infantry, cavalry and artillery, aided by bashi-bazouks, surrounded the city on 12 August. Pitu Guli's band (cheta) tried to defend the town and republic from the Ottoman troops, after a fierce battle near Mečkin Kamen most of the band and their leader (voivode) perished.[7] Another one called battle of Sliva took place at the same time, ending in defeat as well. On 13 August the Ottomans managed to destroy the Kruševo Republic, committing atrocities against the Aromanian and Patriarchist population.[12] As a result of the gunnery, the town was set partially ablaze.[40] After the plundering of the town by the Turkish troops and the Albanian bashi-bazouks, the Ottoman authorities circulated a declaration for the inhabitants of Kruševo to sign, stating that the Bulgarian komitadjis had committed the atrocities and looted the town. A few citizens did sign it under administrative pressure.[41]

Legacy

The celebration of the events in Kruševo began during the First World War, when the area, then called Southern Serbia, was occupied by Bulgaria. Naum Tomalevski, who was appointed a mayor of Kruševo, organized the nationwide celebration of the 15th anniversary of the Ilinden uprising.[44] On the place of the Battle of Mečkin Kamen, a monument and a memorial-fountain were built. After the war, they were destroyed by the Serbian authorities, which continued implementing a policy of forcible Serbianization. The tradition of celebrating these events was restored during World War II in the region, when it was occupied by Bulgaria again.[45]

On the other hand, during World War II, the Macedonian communist partisans developed the idea of historical continuity between their struggle and that of the insurgents of the Ilinden Uprising and Kruševo Republic. The partisan leaders and detachments chose names of heroes from IMRO, one such was Kuzman Josifovski Pitu, named after Pitu Guli.[46] The Kruševo Republic was referred to in the lyrics of the partisan song "Today over Macedonia", later to become the Macedonian anthem. After the war, the idea of socialist continuity proceeded in the newly established Socialist Republic of Macedonia, where the Kruševo Republic was considered as its antecedent.[47] Furthermore, Macedonian historians often compared it to the Paris Commune, the classic symbol of revolutionary socialism. It was emphasized how the Council and commissionerships were evenly split between the nationalities, in a style bound to serve as an example to the Balkans in a similar manner how the Paris Commune served for the world.[48] Another instance firmly praised was the last stand of Pitu Guli and his man in the battle of Meckin Kamen, which achieved an iconic status in the Macedonian national history.[49] The "Ilinden Uprising Museum" was founded in 1953 on the 50th anniversary of the Kruševo Republic in the former house of the Tomalevski family where the Republic was proclaimed. In 1974 an enormous monument, known as Makedonium, was built on the hill above Kruševo, which marked the feat of the revolutionaries and the ASNOM. In the area, there is another monument called Mečkin Kamen commemorating the battle that took place there.[50]

During the Informbiro period, the name of insurgents' leader Nikola Karev was scrapped from the Macedonian national anthem.[51] He and his brothers were suspected of being Bulgarophiles.[52] Nikola Kirov's writings, which are among the most known primary sources on the rebellion, mention Bulgarians, Vlachs (Aromanians), and Greeks (sic: Grecomans), who participated in the events in Kruševo.[53] Although post-World War II Macedonian historians objected to Kirov's classification of Kruševo's Slavic population as Bulgarian, they quickly adopted everything else in his narrative of the events in 1903 as definitive.[54] As a result of the Greek and Bulgarian challenges against the Macedonian identity, Macedonian historians enforced their efforts to prove that IMRO activists had been exclusively Macedonian in identity.[55] The entity is seen as a prelude to its statehood by North Macedonia.[56] Some modern Macedonian historians such as Blaže Ristovski have recognized, that the entity, nowadays a symbol of the Macedonian statehood, was composed of people who identified themselves as "Greeks", "Vlachs" (Aromanians), and "Bulgarians".[57][58] The legacy of the republic is disputed between Bulgaria and North Macedonia.[59] When the anthropologist Keith Brown visited Kruševo on the eve of the 21st century, he discovered that the local Aromanian language still has no way to distinguish "Macedonian" and "Bulgarian", and uses the designation Vrgari, i.e. "Bulgarians", for both ethnic groups.[53] The same has been confirmed by the Greek researcher Asterios Koukoudis.[60] Some authors maintain it was an independent socialist republic, the first in the Balkans.[7][61]

Gallery

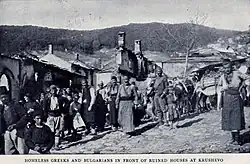

-

The Tomalevski family house where the Republic was proclaimed. The family later emigrated to Bulgaria. In modern day the "Museum of History Kruševo" is located in the house.

-

The Kruševo headquarters in August 1903.

-

The cheta of Pitu Guli near the village of Birino, close to Kruševo, 1903

The cheta of Pitu Guli near the village of Birino, close to Kruševo, 1903 -

The events in Kruševo as seen by the American New York Times; 14 August 1903.

The events in Kruševo as seen by the American New York Times; 14 August 1903. -

Bulgarian postcard representing an insurgent with the flag of Kruševo cheta

-

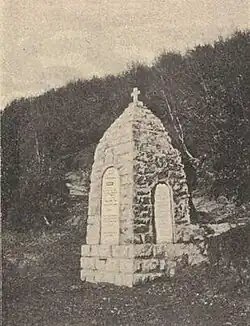

The monument of the Battle of Mečkin Kamen built by the Bulgarian authorities during the First World War.

The monument of the Battle of Mečkin Kamen built by the Bulgarian authorities during the First World War. -

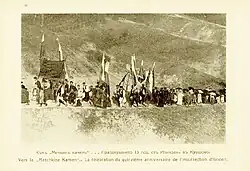

Celebration of the 15th anniversary of the events in Krushevo in 1918 during the Bulgarian occupation of then Southern Serbia.

Celebration of the 15th anniversary of the events in Krushevo in 1918 during the Bulgarian occupation of then Southern Serbia. -

Old comitadji, celebrating Ilinden Uprising in Kruševo in 1943, during the Bulgarian annexation.

Old comitadji, celebrating Ilinden Uprising in Kruševo in 1943, during the Bulgarian annexation. -

Monument dedicated to the Mečkin Kamen battle at the location on which Pitu Guli and his men made their last stand

Monument dedicated to the Mečkin Kamen battle at the location on which Pitu Guli and his men made their last stand -

The monument of the Battle of Sliva, near Kruševo.

The monument of the Battle of Sliva, near Kruševo. -

Ilinden memorial complex, opened on the 71st anniversary of the uprising in 1974.

-

Celebration of Ilinden on 2 August 2011 on Mečkin Kamen, Republic of Macedonia.

Celebration of Ilinden on 2 August 2011 on Mečkin Kamen, Republic of Macedonia.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ De Soto & Dudwick (2000), p. 37.

- ^ Bana Armâneascâ - Nr39-40. Bana Armâneascâ.

- ^ Nadège Ragaru (2023) Bulgaria, the Jews, and the Holocaust. On the Origins of a Heroic Narrative, University of Rochester Press, ISBN 9781648250705, p. 290.

- ^ Marinov, Tchavdar. “We, the Macedonians”. We, the People, Central European University Press, 2009, https://books.openedition.org/ceup/890. In: Diana, Mishkova. We, the People. Central European University Press, 2009, https://books.openedition.org/ceup/866. According to traditional Bulgarian and Macedonian narratives, Kruševo in the vilayet of Manastır, a town inhabited by diverse Christian populations was transformed into an ephemeral “republic” with a temporary revolutionary authority where different “national elements” cooperated. The famous “Kruševo Republic” was led by a local activist of the Internal organization with a socialist orientation—Nikola Karev—and was supposed to have incarnated the principle of supra-national equality.

- ^ Marco Dogo; Stefano Bianchini, eds. (1998). The Balkans: National Identities in a Historical Perspective. Longo. p. 121. ISBN 8880631764.

In liberated Krushevo, the rebel government established itself as a republic, to be remembered in historiography and collective memory as the Krushevo Republic. The Republic, the first of its kind on the Balkans, represented a model of statehood for all of Macedonia and an expression of the revolutionary ideology of TMORO: the "Macedonian Independent Republic" would provide real freedom for the Macedonian people, including minorities, independence, economic, political, cultural and social development.

- ^ John Paul Newman; Balázs Apor, eds. (2021). Balkan Legacies: The Long Shadow of Conflict and Ideological Experiment in Southeastern Europe. Purdue University Press. p. 268. ISBN 1612496695.

The Ilinden Uprising against the Turkish rule in 1903 was one of the most important events in the history of Macedonian people. During the uprising, in the small town of Krusevo the first republic in the Balkans was created. Even though it lasted just for ten days, it had a great impact on the Macedonian liberation movement, especially during World War II and the creation of the Macedonian state as a part of the Yugoslav federation in 1944, as well as on the international community, which was alerted for the existence of the Macedonian people.

- ^ a b c d e f Stoyan Pribichevich (1982). Macedonia, Its People and History. Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 128-129. ISBN 0271003154.

- ^ Alexis Heraclides (2021). The Macedonian Question and the Macedonians: A History. Routledge. p. 44. ISBN 9780367218263.

- ^ Miller (2013), p. 446.

- ^ Kahl (2002), p. 148.

- ^ Rossos (2013), p. 109.

- ^ a b Liotta (2001), p. 293.

- ^ Ristovski (2009), p. 767.

- ^ Bechev (2009), p. 114.

- ^ "Generally, its beginning is attributed to Vasil Glavinov who, in 1896, created the Macedonian(-Adrianopolitan) Social Democratic Group. From the outset, it promoted the autonomist slogan "Macedonia for Macedonians," as well as the internationalist project of a Balkan Federation. The programmatic documents and publications of the Macedonian socialists harshly criticized "Bulgarian chauvinism" and territorial ambitions in Macedonia. Sometimes they even claimed that the Macedonians should not be considered Bulgarians, Serbs or Greeks, as they were, above all, oppressed "slaves." It would nevertheless be farfetched to see in the local socialism an expression of Macedonian national ideology. For instance, the newspaper of the Macedonian socialists explicitly opposed the Serbian idea that the Macedonian Slavs represented a kind of Serbo-Bulgarian "paste" and declared their "purely Bulgarian" character. The "Adrianopolitan" part of the group’s designation shows its commitment to the destiny of the Bulgarians in Thrace as well. It is difficult to place the socialist articulation of the national and social questions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries entirely under the categories of today’s Macedonian and Bulgarian nationalism. If Bulgarian historians today condemn the "national-nihilistic" positions of Glavinov's group, their Macedonian colleagues seem frustrated by the fact that it was not "conscious" enough of Macedonians' distinct ethnic character." Entangled Histories of the Balkans – Volume Two, Roumen Daskalov, Diana Mishkova, Brill, 2013, ISBN 9004261915, p. 503.

- ^ Michalopoulos, Georgios (2014). Parties, Irredentism and the Foreign Ministry: Greece and Macedonia, 1878-1910. Oxford University, pp. 163-164.

- ^ Kostov (2010), p. 71.

- ^ De Soto & Dudwick (2000), pp. 36–37.

- ^ Tanner (2004), p. 215.

- ^ Brown (2003), pp. 81–82.

- ^ Diana (2009), p. 124.

- ^ Kirov-Majski wrote on the history of the IMRO and authored in 1923 the play "Ilinden" in the dialect of his native town (Kruševo). The play is the only direct source containing the Kruševo Manifesto, the rebels' programmatic address to the neighbouring Muslim villages, which is regularly quoted by modern Macedonian history and textbooks. Dimitar Bechev Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia, Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, ISBN 1538119625, p. 166.

- ^ "The Manifesto remains a document with a disputed historical existence. The fact that its origins have thus far been traced only as far as Kirov - Majski's play in 1924 is acknowledged by most people in the town, and one means by which they bridge the two decades of missing provenance to 1903 is to lodge the memory of the text inside Kirov-Majski's head. The belief persists, though, that the document was written and distributed in 1903, as Kirov-Majski himself describes. With regard to the fate of the original, some in Kruševo advance the theory that it was taken by the Ottoman commander back to Constantinople... The fact that no record exists of this original manifesto is explained by the fact that the Turkish archives have never been fully catalogued. Although they have been visited by scholars from various countries, some of those scholars in the Kruševo narrative are deeply invested in the denial of autonomous Macedonian history, and therefore do not wish for documentary proof of Macedonian activism—like the Kruševo Manifesto—to be found. The hidden, inaccessible existence of the "original" Kruševo Manifesto is therefore indefinitely protected. Until such time as the archives are fully catalogued, the existence of the Manifesto cannot be definitively denied. If they are catalogued and the Manifesto's existence recorded, well and good; if the Manifesto is not found, it will be possible to claim that prior to cataloguing, it was destroyed by representatives of a foreign régime that sought to deny the historical roots of Macedonian national autonomy... The Manifesto in the Archives could be argued to enjoy a similar virtual existence, providing untestable and therefore irrefutable evidence of the town's early-twentieth-century commitment to principles of interethnic cooperation that drive its unique claims on the Yugoslav Macedonian state and its successor. For more see: Keith Brown, The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation, Princeton University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-691-09995-2, p. 230.

- ^ Loring M. Danforth (1997). The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World. Princeton University Press. p. 51. ISBN 0691043566.

On August 2, 1903, VMRO led the Macedonian peasantry in the Ilinden Uprising, named after the festival of the Prophet Elijah on which it began. This was one of the greatest events in the history of the Macedonian people. The high point of the Ilinden Revolution was the establishment of the Krushevo Republic in the town of Krushevo in central Macedonia. The leaders of the Krushevo Republic called on all the people of Macedonia, Moslems and Christians alike, to join them in fighting for an independent Macedonia.

- ^ Singleton, Fred (1985). A Short History of the Yugoslav Peoples. Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 9780521274852.

The initial aim of the rising was to create an independent state in the vilayet of Monastir (Bitola), and then to extend the free area to the whole of Macedonia. The appeal was not only to the Slavs, but also to 'Turks, Albanians and Moslems' who suffered under the Ottoman yoke. A 'republic' was established in the town of Kruševo, but the revolt was ruthlessly suppressed after only eleven days.

- ^ Kolstø (2005), p. 284.

- ^ Alexander Maxwell (2007). "Krsté Misirkov's 1903 Call for Macedonian Autocephaly: Religious Nationalism as Instrumental Political Tactic". Studia Theologica. 5 (3): 163.

- ^ MacDermott (1978), p. 387.

- ^ There was even an attempt to form a kind of revolutionary government led by the socialist Nikola Karev. The Krushevo manifesto was declared, assuring the population that the uprising was against the Sultan and not against Muslims in general, and that all peoples would be included. As the population of Krushevo was two thirds hellenised "Vlachs" (Aromanians) and Patriarchist Slavs, this was a wise move. Despite these promises the insurgent flew Bulgarian flags everywhere and in many places the uprising did entail attacks on Muslim Turks and Albanians who themselves organised for self-defence." Who are the Macedonians? Hugh Poulton, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 1995, ISBN 1850652384, p. 57.

- ^ Michael Palairet (2016). Macedonia: A Voyage through History. Vol. 2. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 149. ISBN 1443888494.

- ^ a b Brown (2018), pp. 71, 191–192.

- ^ Diana (2009), p. 125.

- ^ Keith Brown, Loyal Unto Death: Trust and Terror in Revolutionary Macedonia, Indiana University Press, 2013, ISBN 9780253008473, pp. 141–142.

- ^ MacDermott (1978), p. 311.

- ^ Aromanian consciousness was not developed until the late 19th century, and was influenced by the rise of Romanian national movement. As result, wealthy, urbanized Ottoman Vlachs were culturally hellenised during 17–19th century and some of them bulgarized during the late 19th and early 20th. century. Raymond Detrez, 2014, Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 1442241802, p. 520.

- ^ Коста Църнушанов, Македонизмът и съпротивата на Македония срещу него, Университетско изд. "Св. Климент Охридски", София, 1992, стр. 132.

- ^ Андрей (1996), pp. 60–70.

- ^ Rossos (2013), p. 105.

- ^ Jowett (2012), p. 21.

- ^ a b Phillips (2004), p. 27.

- ^ Gross (2018), p. 128.

- ^ Dimitar Bechev Historical Dictionary of North Macedonia, Rowman & Littlefield, 2019, ISBN 1538119625, p. 124.

- ^ Dragi Ǵorǵiev, Lili Blagaduša, Documents Turcs sur l'insurrection de St. Élie provenants du fonds d'archives du Sultan "Yild'z", Arhiv na Makedonija, 1997, p. 131.

- ^ Цочо В. Билярски, Из рапортите на Наум Томалевски до ЦК на ВМРО за мисията му в Западна Европа; В „Иван Михайлов в обектива на полиция, дипломация, разузнаване и преса“, Университетско издателство "Св. Климент Охридски", 2006, ISBN 9789549384079.

- ^ Miller (1975), p. 128.

- ^ Daskalov & Mishkova (2013), p. 535.

- ^ Roudometof (2002), p. 61.

- ^ James Krapfl, "The Ideals of Ilinden: Uses of Memory and Nationalism in Socialist Macedonia" in John S. Migel, (ed.), State and Nation Building in East Central Europe: Contemporary Perspectives, Institute on East Central Europe, Columbia University, 1996, ISBN 096545200X, pp. 297-316

- ^ Keith Brown (2013). Loyal Unto Death: Trust and Terror in Revolutionary Macedonia. Indiana University Press. p. 142. ISBN 9780253008473.

- ^ Meckin Kamen monument – Travel to Macedonia.

- ^ Kolstø (2016), p. 188.

- ^ Brown, Keith (2018). The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. Princeton University Press. p. 191. ISBN 9780691188430.

The weapons that Tito's regime used against ideological enemies varied across Yugoslavia: one tactic was to label his enemies as doctrinaire Stalinists or cominternists, who were thereby opponents of his vision of Yugoslavism. In Macedonia, resisters also found themselves under attack for pro-Bulgarianism—a rhetorical strategy that some Macedonian politicians continued to use even in the 1990s. In 1993 Mise Karev suggested that this policy had been pursued against the dead, including Nikola Karev. The post-war pro-Yugoslav leadership in Macedonia, he said, and especially Lazar Kolisevski, "wanted history to start with themselves," and they were jealous of the hold that Ilinden's leaders had on the imagination of the people. They sought to devalue that legacy by denouncing many of the personalities involved as Bulgarian.

- ^ a b Kostov (2010), p. 71.

- ^ Brown (2003), p. 81.

- ^ Frusetta (2004), pp. 110–117.

- ^ Eltion Meka; Stefano Bianchini, eds. (2020). The Challenges of Democratization and Reconciliation in the Post-Yugoslav Space. Nomos. p. 50. ISBN 9783848769049.

- ^ "Беше наполно прав и Мисирков во своjата фундаментална критика за Востанието и неговите раководители. Неговите укажуваньа се покажаа наполно точни во послешната практика. На пр., во ослободеното Крушево се формира градска управа составена од "Бугари", Власи и Гркомани, па во зачуваните писмени акти не фигурираат токму Македонци(!)..." Блаже Ристовски, "Столетиjа на македонската свест", Скопје, Култура, 2001, стр. 458.

- ^ "We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe" Diana Mishkova, Central European University Press, 2009, ISBN 9639776289, p. 124: Ristovski regrets the fact that the "government" of the "republic" (nowadays held to be a symbol of Macedonian statehood) was actually composed of two "Greeks", two "Bulgarians" and one "Romanian". cf. Ristovski (2001).

- ^ When I passed through Skopje in December 2003, I saw large banners that celebrated 100 years of Macedonian statehood. Whatever the merits of the 1903 Ilinden uprising and the ephemeral Kruševo Republic that lasted a mere week, it is hardly possible to elevate it to the level of statehood and the Macedonian identity of the rebels is also in question. It goes without saying that it is impossible to find some sort of common ground between these approaches. The most serious polemics along these lines have been between Bulgaria and Macedonia. For more see: Aarbakke Vemund (2011). Images of imperial legacy: The impact of nationalizing discourse on the image of the last years of Ottoman rule in Macedonia. Images of Imperial Legacy, Modern Discourses on the social and cultural impact of Ottoman and Habsburg rule in Southeast Europe. Επιμέλεια:Tea Sindbæk, Maxmilian Hartmuth. p.115-128.

- ^ Asterios I. Koukoudēs (2003) The Vlachs. Metropolis and Diaspora. Zitros, ISBN 9789607760869, p. 33.

- ^ Lauren S. Bahr, ed. (1997). Collier's Encyclopedia: With Bibliography and Index. Collier's. p. 160. LCCN 96084127.

Sources

- Андрей, Даниела (1996). Големите власи сред българите: ономастична просопография (in Bulgarian). Знак`94. ISBN 978-954-8709-08-8.

- Bechev, Dimitar (2009). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Macedonia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6295-1.

- Brown, Keith (2003). The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09995-2.

- Brown, Keith (2018). The Past in Question: Modern Macedonia and the Uncertainties of Nation. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691188430.

- Daskalov, Roumen; Mishkova, Diana (2013). Entangled Histories of the Balkans - Volume Two: Transfers of Political Ideologies and Institutions. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-26191-4.

- De Soto, Hermine G.; Dudwick, Nora (2000). Fieldwork Dilemmas: Anthropologists in Postsocialist States. Univ of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-16374-7.

- Frusetta, James (2004). "Common Heroes, Divided Claims: IMRO Between Macedonia and Bulgaria". Ideologies and National Identities. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9241-82-4.

- Gross, Feliks (2018). Violence in politics: Terror and political assassination in Eastern Europe and Russia. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. ISBN 978-3-11-138244-9.

- Jowett, Philip (20 March 2012). Armies of the Balkan Wars 1912–13: The priming charge for the Great War. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-84908-419-2.

- Kahl, Thede (2002). "The Ethnicity of Aromanians after 1990: the Identity of a Minority that Behaves like a Majority". Ethnologia Balkanica. 6. LIT Verlag Münster: 145–169.

- Kolstø, Pål (2005). Myths and boundaries in south-eastern Europe. Hurst & Co. ISBN 1850657726.

- Kolstø, Pål (2016). Strategies of Symbolic Nation-building in South Eastern Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-04936-4.

- Kostov, Chris (2010). Contested Ethnic Identity: The Case of Macedonian Immigrants in Toronto, 1900–1996. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-0343-0196-1.

- Liotta, P. H. (2001). Dismembering the State: The Death of Yugoslavia and why it Matters. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-0212-1.

- MacDermott, Mercia (1978). Freedom Or Death: The Life of Gotsé Delchev. Pluto Press. ISBN 0904526321.

- Miller, Marshall Lee (1975). Bulgaria During the Second World War. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0870-8.

- Miller, William (2013). Ottoman Empire and Its Successors 1801–1927: With an Appendix, 1927–1936. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-68659-5.

- Diana, Mishkova (2009). We, the People: Politics of National Peculiarity in Southeastern Europe. Central European University Press. ISBN 978-963-9776-28-9.

- Palairet, Michael (2016). Macedonia: A Voyage through History (Vol. 2, from the Fifteenth Century to the Present). Cambridge Scholars. ISBN 978-1-4438-8849-3.

- Phillips, John (2004). Macedonia: Warlords and Rebels in the Balkans. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 0857714511.

- Rossos, Andrew (2013). Macedonia and the Macedonians: A History. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-4883-2.

- Roudometof, Victor (2002). Collective Memory, National Identity, and Ethnic Conflict. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-2759-7648-4.

- Ristovski, Blaže (2009). Macedonian Encyclopedia (in Macedonian). Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts. ISBN 978-6-0820-3023-4.

- Tanner, Arno (2004). The Forgotten Minorities of Eastern Europe: The history and today of selected ethnic groups in five countries. East-West Books. ISBN 952-91-6808-X.

Sources

- Силянов, Христо. Освободителните борби на Македония, т. I, София 1933, гл. VI.1 (in Bulgarian)

- 13-те дена на Крушевската република, Георги Томалевски (in Bulgarian)