Matei Ghica

| Matei Ghica | |

|---|---|

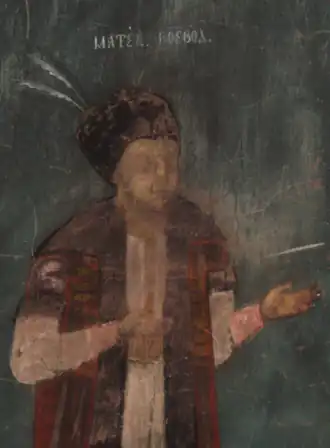

Ghica in 1753; Eforia Spitalelor Civile portrait | |

| Prince of Wallachia | |

| Reign | 4 September 1752 – June 1753 |

| Predecessor | Grigore II Ghica |

| Successor | Constantin Racoviță |

| Prince of Moldavia | |

| Reign | June 1753 – 19 February 1756 |

| Predecessor | Constantin Racoviță |

| Successor | Constantin Racoviță |

| Born | c. 1720 |

| Died | after 1777 |

| Spouse | Smaranda Bassa Mihali (div. c. 1756) |

| Issue | Zoe Costache-Talpan |

| House | Ghica |

| Father | Grigore II Ghica |

| Mother | Zoe (Zoița) Manos |

| Religion | Orthodox |

| Signature |  |

Matei or Mateiu Grigore Ghica (Albanian: Matei Gjika; Greek: Ματθαίος Γκίκας, romanized: Matthaios Ghikas; Romanian Cyrillic and Church Slavonic: Матею Гика;[1] Turkish: Matei Gika; French: Mat[t]hieu Ghika; c. 1720 – after 1777) was the Prince of Wallachia between 4 September 1752 and June 1753, and Prince of Moldavia between June 1753 and 19 February 1756. A member of the Ghica family, he was the son of Grigore II Ghica, grandson of Alexander Mavrokordatos the Exaporite, and brother of Scarlat Ghica; he thus belonged to the Phanariotes, a group of Greek-speaking and Christian aristocrats who performed political and bureaucratic services for the Ottoman Empire. During Matei's childhood and youth, Grigore, having served as Chief Dragoman, had similarly moved between the throne of the two Romanian-speaking tributary principalities. Matei himself was first attested with his father in Moldavia, where he is known to have been homeschooled in Greek during the late 1720s. He fled that country during the Russo-Turkish War of 1735–1739, after which Grigore lost his throne and his political influence.

In the 1740s, as Grigore reemerged from exile and took the throne of Wallachia, Matei was fated for political advancement. He became Chief Dragoman at the court of Sultan Mahmud I in 1751, but was completely uninterested in the office, leaving it to be run by his father-in-law, George Bassa Mihali. He allegedly disappointed his father, who, before his death in 1752, pleaded to be succeeded by Scarlat; Matei outmaneuvered his brother, and obtained the throne for himself. He continued some of his father's policies, including when it came to expanding Bucharest, but also angered the native boyars, as well as many commoners, by flagrantly indulging the Greek community. He was pressed out of the country by an uprising that earned support from the Wallachian Orthodox Church; Mahmud instead assigned him as ruler of Moldavia, moving the Moldavian prince, Constantin Racoviță, to Wallachia.

In his significantly longer period as Moldavian ruler, Matei placated the local boyardom to the point of being identified as its instrument. He was primarily focused on expanding his activities as a patron (ktitor) of the Eastern Orthodox Church, and on repairing the princely court of Iași. He spied on the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which was Moldavia's powerful neighbor, and, during his last days on the throne, lavishly entertained a caravan of Polish diplomats. Matei's ouster signaled personal disaster, rendered acute when he divorced Lady Smaranda. He withdrew from high-politics until 1777, when he made a final and ill-fated attempt at obtaining the Wallachian throne; he was part of a conspiracy which had marginal support from the Russian Empire, and, though he simply walked away from the affair, he saw his supporters severely punished by the Sublime Porte. He died at an unknown date, leaving only a daughter, who returned to Moldavia.

Origins and early life

The Ghica family was ultimately of Albanian origin. It was first attested c. 1600 at Köprülü[2] or Ioannina,[3] before becoming intertwined with the Phanariote aristocracy in Istanbul. A late-18th-century account by the Wallachian boyar Matei Cantacuzino described the Ghicas as first entering Moldavia with Matei Ghica's paternal great-great-grandfather, Grigore, who traded there in the 1630s. This was during the reign of Vasile Lupu, who made him a Postelnic and a permanent envoy to the Sublime Porte (Kapucu).[4] His son, known as Grigore I Ghica, became Prince of Wallachia in the 1660s, as the first of the dynasty to ascend to the throne of either principality; his wife Maria was from the Sturdza family, which belonged to Moldavia's boyardom.[5] Their son, also named Matei, had only served as Dragoman, in 1727. His wife, and Matei Jr's grandmother, was Princess Roxana or Roxandra, a member of the Mavrokordatos family and daughter of Alexander the Exaporite.[6] The two Mateis are sometimes confused, leading some authors to describe Roxana, a highly educated woman, as Matei Jr's wife (on the basis of this identification, she is called the first female physician in Romanian history).[7]

Clan records indicate that Matei Jr himself was born in 1728 as the oldest child of Grigore II,[8] who was had served as Dragoman of the Porte and had begun his first reign in Moldavia, and his wife Zoe "Zoița" Manos, daughter of the physician-philosopher Michail Manos.[9] Museologist Colette Axentie describes her as Greek, noting that she was "beautiful, intelligent, and energetic."[10] The progeny also included (in reported chronological order): George, Grigore, Smaragda, and Scarlat.[11] The details of his birth and age are contested by other sources. In their 1727–1730 letters to Chrysanthus Nottara, both Grigore and Zoe refer to their several children as growing up. One of the sons is mentioned therein as Chrysanthus' godson, and they are all revealed to have been educated in Iași by the monk Ioannikios.[12] In late 1727 and early 1728, the entire family, including Roxana, was attested in Hotin Fortress, then at Iași—except for the ruler, who was fighting the Budjak Horde in Tigheci.[13]

One Wallachian manuscript reports that Matei was "aged thirty" in 1752;[14] an inventory of other sources also shows that he was believed to have been aged 23, 25, or 27 that same year.[15] Confusion endures as to Matei and Scarlat's respective positions in the family, with some contemporaries such as Ianache Văcărescu[16] and Atanasiu Comnen Ipsilanti,[17] as well as modern historians such as Gheorghe Diaconu,[18] reporting that Scarlat was the older brother. Similarly, their exact status in respect to the principalities is a topic of contention: while technically included among the Phanariotes, and therefore perceived as oppressive foreigners, they are believed by historian Panait I. Panait to have actually been "already naturalized" in the two countries as children or youths, along with much of their family.[19] By contrast, Axentie describes their father as "almost completely Hellenized".[20] Highly proficient in Greek, Ottoman Turkish, and several European languages, he had learned to speak Romanian, in its Moldavian dialectal form, as early as 1726.[21]

Of the Ghica boys, only Matei and Scarlat were likely alive during the Russian occupation of 1735–1739, which chased the family, as well as all of Moldavia's leading boyars, out of Iași. Essayist Kelemen Mikes, who was present in Iași in August 1739, wrote that Grigore "has left the city" in the wake of a likely Cossack raid, while Matei and Scarlat "are nowhere to be found."[22] Closely affiliated with the court, Ipsilanti added that Grigore had fled for safety in Galați, and had sent one of his sons deep in Ottoman territory, at Isaccea.[23] The reigning Sultan, Mahmud I, ordered Grigore to relinquish his throne in September 1741, but he reportedly continued to regard himself as "always and all times a Prince".[24] Grigore's brother and successor as Dragoman, Alexander Ghica, who had angered Mahmud during the negotiations at Belgrade,[25] was put to death in 1741. Matei, his nephew, inherited his pew in St. George's Cathedral.[26]

Becoming Dragoman

In 1747, after a brief banishment to Tenedos, Grigore began his third rule over Moldavia.[27] However, the Ghicas were by then set on obtaining control of Wallachia. A hostile account by Mihai Cantacuzino places Matei in Istanbul, where he was currying favor for his father by denouncing Wallachia's ruler, Constantine Mavrocordatos. According to this source, Matei reported on how Constantine had allowed young boyars, including Răducanu Cantacuzino, to leave for the Republic of Venice; ostensibly, they were there to study, but they also apparently took with them part of the princely treasury, for safekeeping—something which the Porte could not accept.[28] Only nine months into his Moldavian reign, having also generously bribed the Ottoman treasurer (Hazinedar Süleyman),[29] Grigore was granted the Wallachian throne. Both Matei and Scarlat eventually followed Grigore to Bucharest, each using the title of Beizadea—indicating their status as aspirant Princes.[30] The Ghicas as a whole were unusually frugal, inhabiting Mihai Vodă Monastery (their nominal palace, Curtea Veche, having by then fallen into disrepair), and sometimes a small house in Pantelimon.[31] The monarch and his two sons are painted together in a mural at Mărcuța Church, also located in Pantelimon;[32] the junior princess, Smaragda, died at some point before 1750, leaving a daughter.[33]

According to historian Nicolae Iorga, Grigore devised of a plan to make Matei into a Dragoman, since this position would have ensured him political friends, and would have then singled him out for the throne in either Wallachia or Moldavia. He was initially prevented from obtaining that position by the intrigues of other candidates, including those representing other branches of the Ghica family.[34] Matei was married off to the daughter of George Bassa Mihali (or Gheorghe Bașa-Mihalopol), who was serving as Wallachia's Hatman and Kapucu.[35] His wife's name is attested as "Lady Smaranda" by a diptych of Golia Monastery[36] and by letters she exchanged with Sylvester Dabbas, the Patriarch of Antioch.[37] Her tomb in Mărgineni reportedly uses the variant "Smaragda".[38]

The Beizadea finally obtained appointment as Dragoman in 1751, replacing the much older John Theodore Callimachi. In preparation, Prince Grigore and Bassa Mihali had bribed other officials at the Ottoman court and had "quietly transported [Matei] out of Bucharest."[39] In his review of Ottoman justifications, historian Sezai Balcı sees Matei as "chosen for his maturity, intelligence, loyalty, and sincerity, despite being 23 [sic] years old."[40] His arrival was initially regretted by the French mission to the Porte, who had regarded Callimachi as a Francophile.[41] As a Dragoman, young Ghica ended up pleasing the French diplomats: born into wealth, he was not interested in perpetuating graft, meaning that the envoys had to spend less money on ensuring his favors.[42] Moreover, he was himself the subject of wanton persecution by the Pashas, who expressed interest in confiscating his estates for their own use.[43] The positive assessments are contradicted by other witnesses. As a figure of the Moldavian court, Enache Kogălniceanu depicted Matei as a violent and haughty drunkard; this verdict was partly backed up by the French ambassador, Roland Puchot.[44] Ipsilanti alleged that Matei was an incompetent and indifferent Dragoman, the attributes of his office being actually exercised by his father-in-law, as well as by his secretaries—Lukaki della Rocca and Iakovaki Rizo.[45]

Grigore, meanwhile, obtained that his own rule in Wallachia be extended. He died on his throne in August 1752. According to Comnen Ipsilanti, his cause of death was an error by his father-in-law, who had medicated him with theriac;[46] Ghica family tradition partly agrees with this claim.[47] Ipsilanti claims that Grigore had come to resent Matei, and wanted Scarlat as his only heir. Though the boyars were made to swear subjection to Scarlat, Matei benefited from Bassa Mihali's great influence, and managed to defeat the opposition.[48] This also required the pair to bribe Mahmud with the "enormous sum" of 3,200 bags of coinage (calculated by Iorga at 1 million lei in 1902 currency); in exchange, he received not just his father's throne, but also his entire mobile wealth.[49] Officially beginning his reign on 24 August Old Style (4 September in New Style),[50] Matei was reportedly enthusiastic about leaving behind the office of Dragoman, which he had grown to dislike, and which went back to Callimachi that same month.[51]

Wallachian rule and ouster

Matei returned to Bucharest alongside a lage retinue of Ottoman Greeks. He only reached his capital in late 1752, as one of the few princes of that decade to begin his reign in autumn or winter.[52] A contemporary account dates his arrival to October 7261 Anno Mundi.[14] Ianache Văcărescu more precisely uses 1 (New Style: 12) October,[53] as does an unsigned Greek ledger.[54] Bassa Mihali never followed, but continued to support his son-in-law from Istanbul. Instead, the new monarch was more directly advised by two members of the Soutzos family (a newly promoted section of the Phanariote class), as well as by the acting Spatharios, Nicolae Roset,[55] who had married Bassa Mihali's other daughter.[56] The prince is also known to have favored regular immigrants such as Costin Ologul of Metsovo. The latter, a victim of frostbite, had had had his toes amputated at Colțea Hospital (the first operation known to have been performed there), and was granted a farm carved out of the prince's estate.[57] Matei also banished the leader of the boyar opposition, Pârvu Cantacuzino, who was banished from Wallachia "for a full year", and then similarly retaliated against Pârvu's brother and political ally, Mihai.[58]

Matei intervened to strengthen some of Grigore's core policies. The Russian surveyor Friedrich Wilhelm Bauer observed that Ghica junior had nominally reduced the fiscal burdens, or sferturi, in the form introduced by Grigore, but in tandem had increased the number of payments owed by each subjects.[59] In two writs of October 1752, the young monarch applied his father's philosophy in education, which was to have schools of the Wallachian Orthodox Church financed by a tax levied on parish priests.[60] Also like his father, Matei was interested in colonizing the outskirts of Bucharest, donating for the construction of a guild church in Broștenilor mahala, south of Curtea Veche.[61] Finding that Giulești was irresistibly beautiful, he commissioned a pavilion, which replaced one constructed by Grigore. The building does not survive, but it is presumed by architects to have been rather grandiose, in the style of Istanbul's yalı dwellings.[62] Its construction was supervised by Dumitraki Soutzos, who was the acting Aga (police superintendent).[63] In January 1753, Matei honored "the blessed Grigore Ghica" by resuming his donations to the Monastery of Saint John the Theologian on Patmos. These were set a sum of 30 Thaler, reserved from the Wallachian salt mines and paid annually.[64] He similarly ensured the upkeep of Pantelimon Hospital, with an annual grant of 2,500 Thaler, all obtained from the mining town of Ocnele Mari.[65] Like his father and his brother, Matei had his portrait painted as a patron of charities (it survived as a modern copy at Eforia Spitalelor Civile).[66]

Matei immediately alienated the local boyardom by promoting his Greek proteges as boyars in exchange for modest bribes, said to have at least once included "some yards of cloth"; over a few days, he created thirty Stolnici, twenty Paharnici, and fifty Serdari.[67] The opposition organized in a form that, as Panait reports, was unprecedented, since it required a "collaboration of all the classes" (though still "lacking a clear platform").[68] This coalition sent Medelnicer Ștefanachi, who had been sidelined by Ghica, to approach the Sultan in Istanbul. He prostrated before Mahmud in the courtyard of Eyüp Sultan Mosque, handing him a supplication of the native boyars.[69] Matei's indifference to local custom was also rated as insulting by the Wallachian Church, whose Metropolitan, Neofit Cretanul, agreed to preside upon the boyars' anti-Phanariote movement (despite being a foreigner himself).[70] In the Ghica family chronicles, it is alleged that Neofit, an ailing man, had been fed "strong medicine" by his bribed-off physician, making him "lose his mind" ahead of joining the revolt.[71]

An Ottoman official, Hagi Mustafa, was dispatched to Bucharest, where, on 21 May 1753, he watched on as a mass of boyars and commoners marched in protest before him.[72] This moment is seen by Panait as highly disruptive for the established order, since "the streets of the city were under the authority of the popular masses", leading boyars such as Barbu and Ștefan Văcărescu to flee from Bucharest.[73] Mahmud decided to punish men involved on both sides of the controversy: in June 1753, Bassa Mihali was sent into exile alongside Roset, Ștefanachi, and the rebel Constantin Dudescu, just as Matei was ordered to take up the Moldavian throne—whose previous holder, Constantin Racoviță, had similarly alienated his subjects.[74] In a historically unprecedented move, Racoviță took the throne in Bucharest, where he was met with other forms of sabotage and opposition.[75] Neofit is believed to have died of his ailment on the exact day that Matei was leaving Bucharest.[76] According to the historian Jean-Paul Besse, the prelate had in fact been poisoned by the disgruntled and outgoing monarch.[77] The exact date of these twinned events is unknown, but the exchange of thrones is certain to have occurred before 3 July.[78]

Moldavian rule

From his new position, Matei was able to talk the Ottomans into forgiving his own camp. From August, his new court of Iași grew to include the Soutzoses (appointed as Postelnici) and Iakovaki Rizo, now made Spatharios.[79] However, the prince was more submissive in his treatment of the native Moldavian boyars, to the point where, as Kogălniceanu argues, he gave them prea mult maidan ("too much license").[80] According to Kogălniceanu, he organized zăfchiuri ("magic-parties") where he celebrated with boyars and especially boyaresses. These ended with him and his wife watching impromptu dancing by the ladies of the court, as well as by local Jewish women.[81] In November 1754, he approved of an increase in boyar revenues, allowing them to engage in various forms of tax farming.[82] Matei attempted a similar treatment of the Moldavian commoners, and, in August 1753, awarded lifetime tax exemptions to most captains of the Moldavian military forces.[83] Almost immediately after taking the throne, Matei had reduced the fiscal toll on shepherds arriving in from Transylvania, setting the oierit tax at a low level. He failed to maintain this provision, raising the tax and introducing another one, to the anger of the returning shepherds.[84] In June 1754, he ordered some of the revenue from such tolls to be used by the monks of Patmos,[85] later conceding that the boyars too could tax the shepherds by head of cattle.[86]

Matei maintained some points of continuity with Racoviță, whose sister Anastasia had married Scarlat.[87] He continued the restoration works at Popăuți Monastery, which had been inaugurated by Prince Constantin's mother, and donated the establishment to the Patriarchs of Antioch.[88] Early on, he was asked to intervene in favor of a doctor, Giuseppe Antonio Pisani, wrongly accused of having murdered Racoviță's wife Sultana. He refused to pardon Pisani until persuaded by Ambassador Puchot.[89] Matei had also inherited from Racoviță the effort to restore the princely court, which had been largely devastated by a fire. Though he tried to rebuild his consort's quarters, conventionally known as the "harem", he never had the time to do so.[90] He is however known to have rebuilt the local chapel, known as Doamnei Church, which he furnished with an outstanding iconostasis, and to have allowed its parish priest, Iftimie, to purchase property in the city.[91] His other work on the palace complex was largely inspired by his late father: he added standpipes to a fountain that had already been commissioned by Grigore.[92] Matei was additionally a ktitor of the church in Huși, where he was painted alongside the bishop of the eponymous diocese, of the skete in Brădicești, and of Tărâță Monastery in Bârnova.[93] A full-length portrait of his in princely regalia, believed by Iorga to have been done by a Western muralist, appears in his father's Frumoasa Monastery.[94]

While at Iași, Matei was keen on supervising the relations between his realm and its neighbors to the north, primarily including the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. He persuaded the Sultan to allow the return of some 4,000 Moldavian taxpayers, who had previously fled into Turkish Hotin and the various Polish provinces surrounding it.[95] In 1753, a Greek man, John Leonardi, was his permanent envoy to Zhvanets;[96] at around the same time, his Staroste in Cernăuți, and diplomatic liaison for the Poles, was the Frenchman Jean Mille, a naturalized ancestor of the actor Matei Millo.[97] Among those visiting Moldavia during Matei's rule was the Ragusan scientist Roger Joseph Boscovich. The Prince befriended him, and in 1754 sent him to Poland as his spy.[98] In early February 1756, Matei received at Iași the Polish diplomat Jan Karol Wandalin Mniszech, who was traveling to Istanbul; he and his guest discussed with each other in Neo-Latin.[99] One account of the journey reports that Matei received Mniszech at the head of the Moldavian soldiers—comprising "six companies", as well as hundreds of bashi-bazouks and uhlans.[100] Mniszech was entertained by the princely couple at the court, where they reportedly witnessed another one of Matei's zăfchiuri.[101] The two men exchanged gifts: Mniszech received a Moldavian steed, while Matei was granted a mechanical watch (and Smaranda a coffeeset).[102]

Later life

Matei was deposed by his Ottoman overlord, now Osman III, within weeks of the Mniszech encounter—the date of his ouster is given as 19 February 1756 in diplomatic correspondence coming out of Pera.[103] He therefore had the contextually rare distinction of reigning uninterruptedly in either principality between his father's death and 1756.[104] Racoviță took over, and again tried to restore the palace, but was himself deposed by the Ottomans in March 1757.[105] While his brother and rival was able to make a final return as ruler of Moldavia after that episode, Matei himself was a destitute. Kogălniceanu recounts that he had had a fallout with Bassa Mihali, and had divorced his daughter. As a result, the two families took each other to court, under the Ottoman confessional system.[106][107] The experience ruined him financially, and, according to Kogălniceanu, he was "at the mercy of other Christians".[108]

Matei was still in Istanbul after the Russo-Turkish war of 1768–1774, which ended with the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca and introduced Russia as a permanent supervisory power in Wallachia and Moldavia. In early 1777, he tried to obtain the Wallachian throne by staging an elaborate intrigue against the titular ruler, Alexander Ypsilantis.[107][109] The events are largely known through reports made by Claude-Charles de Peyssonnel, former French ambassador to the Crimean Khanate. According to Peyssonnel, Ghica agreed to come out of political retirement after being begged to do so by Ypsilantis' subjects. The enterprise required support from two Franco-Turkish intriguers, namely Glavani and Jean Dunant, as well as crucial backing from men who claimed to represent Russia—Sergei Laskarov and Vasily Tomara; this group also claimed to have obtained approval from Prince Repnin, who had direct political influence over the two principalities.[110] As Peyssonnel reports, both Matei and Repnin lost confidence in their backers, realizing that the conspiracy promised more than it could deliver. Ghica asked Glavani to return his contribution, amounting to "several thousand piasters". This created a panic, forcing Repnin to intervene—his solution was to make Ypsilantis pay for the preservation of his throne, as a result of which Ghica received the equivalent of some 400 bags of currency, of which 200 were sent in as "very valuable presents".[111]

Peyssonnel recounts that a "powerful party" of Ghica-supporting boyars existed in Wallachia, until Repnin betrayed it. He took the boyars' bribes, but afterwards delivered them to the Dragoman, Constantine Mourouzis, who was Ypsilantis' ally and in-law, and stood by as they were rounded up and deported to an undisclosed location.[112] Matei himself was not touched by such repression, and appears to have switched focus on his links with Moldavia. A portrait of his as an old man exists at Iași, but, as Iorga observes, it was either sent in by Ghica himself, out of Istanbul, or is entirely fanciful.[113] He is presumed by genealogist Eugène Rizo-Rangabé to have died childless,[114] while another scholar, Vasile Panopol, mentions a daughter Zoe—married off to the Moldavian Vasile Costache-Talpan, she was memorialized by the Zoei Street of Iași.[115] Little is known about her mother Smaranda beyond the fact of her burial at Mărgineni; the grave was later said to have been looted, possibly by a parish priest.[38] Scarlat had a surviving son, Alexandru, who reigned briefly in Wallachia in the 1760s, and with whom that branch of the Ghicas came to its end.[116]

Notes

- ^ Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou & Mircea, p. 290

- ^ Carra et al., p. 57; Rizo-Rangabé, p. 45

- ^ Vlad, p. 987

- ^ Vlad, p. 987

- ^ Rizo-Rangabé, p. 45. See also Păun, pp. 122–123

- ^ Rizo-Rangabé, p. 46. See also Axentie, p. 92; Iorga (1917), pp. 786, 802–803, 840–841, 900, 903, 912, 920–921, 1216; Păun, p. 122; Sinigalia, p. 8; Vlad, pp. 987–988

- ^ Samarian, p. 24

- ^ Rizo-Rangabé, p. 49

- ^ Axentie, pp. 92, 93; Sinigalia, p. 8; Vlad, pp. 988–989, 999. See also Holban et al., p. 150; Păun, p. 122

- ^ Axentie, p. 92

- ^ Rizo-Rangabé, p. 49

- ^ Iorga (1917), pp. 912, 921–922, 963, 985, 1044

- ^ Iorga (1917), pp. 934–937, 952–953, 958–959, 962–963

- ^ a b Ilie Corfus, Însemnări de demult, p. 9. Iași: Editura Junimea, 1975

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxxii

- ^ Chițulescu, pp. 181, 182

- ^ Iorga (1917), p. 1130

- ^ Diaconu, p. 187

- ^ Panait, pp. 177–178

- ^ Axentie, p. 92

- ^ Vlad, p. 988

- ^ Holban et al., p. 205

- ^ Iorga (1917), p. 1094

- ^ Vlad, p. 999

- ^ Rizo-Rangabé, p. 46

- ^ Iorga (1917), p. 1104

- ^ Axentie, p. 92; Iorga (1917), pp. 1114–1115, 1119–1120. See also Sinigalia, p. 8

- ^ Ștefan Meteș, "Zugravii Bisericilor Române", in Anuarul Comisiunii Monumentelor Istorice. Secția pentru Transilvania, 1926–1928, p. 137

- ^ Iorga (1917), p. 1121

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxix

- ^ Axentie, pp. 92–93

- ^ Iorga (1930), pp. xiv, 164

- ^ Iorga (1917), pp. 1124–1125

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxix

- ^ Diaconu, p. 187; Iorga (1902), pp. lxx–lxxiii; Rizo-Rangabé, p. 49

- ^ Iftimi, p. 210

- ^ Diaconu, pp. 187, 189–190

- ^ a b Andreea Cașcaval, "Mărgineni – Bacău. Bijuteriile Principesei Ghica", in Jurnalul Național, 15 March 2004, p. 27

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxx. See also Iorga (1917), p. 1130

- ^ Sezai Balcı, "Osmanlı Devleti'nde Tercümanlık", in Mehmet Alaaddin Yalçınkaya, Uğur Kurtaran (eds.), Osmanlı Diplomasi Tarihi. Kurumları ve Tatbiki. Ankara: Grafiker Yayınları, 2018. ISBN 978-605-2233-10-8

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxii

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxv

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxviii

- ^ Iorga (1902), pp. lxxii, lxxv

- ^ Iorga (1902), pp. lxxii–lxxiii

- ^ Axentie, p. 93; Iorga (1917), p. 1130. See also Iorga (1902), p. lxxii

- ^ Vlad, p. 999

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxxii & (1917), p. 1130

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxxiii

- ^ Chițulescu, p. 181

- ^ Iorga (1902), pp. lxxiii–lxxiv

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxxxiii

- ^ Chițulescu, pp. 181, 182

- ^ Iorga (1917), p. 1132

- ^ Iorga (1902), pp. lxxiv–lxxvi & (1917), pp. 1130–1131

- ^ Diaconu, pp. 187, 189–190

- ^ Samarian, p. 161

- ^ Giorge Pascu, "Mihail Cantacuzino", in Cercetări Istorice, Vol. I, Issue 1, 1925, p. 66

- ^ Carra et al., p. 165

- ^ George Potra, "Articole și studii. Contribuții documentare la 'Școala Domnească de slovenie de la Biserica Sf. Gheorghe-Vechi din București'", in Glasul Bisericii, Vol. XXV, Issues 3–4, March–April 1966, pp. 251, 256–258

- ^ Păun, p. 124

- ^ Sinigalia, pp. 8–9. See also Gheorghe Vasilescu, "Din istoricul cartierului Giulești", in București. Materiale de Istorie și Muzeografie, Vol. IV, 1966, p. 155

- ^ Sinigalia, p. 9

- ^ Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou & Mircea, pp. 287–291

- ^ V. A. Urechia, Edilitatea sub domnia luĭ Caragea, p. 564. Bucharest: Romanian Academy & Institutul de Arte Grafice Carol Göbl, 1900

- ^ Iorga (1930), pp. xiv, 169

- ^ Iorga (1902), pp. lxxiv–lxxv & (1917), pp. 1130–1131

- ^ Panait, p. 179

- ^ Al. A. Vasilescu, p. 372. See also Iorga (1902), p. lxxvi

- ^ Besse, pp. 20–22; Holban et al., p. 335; Iorga (1902), p. lxxvi & (1917), p. 1131; Al. A. Vasilescu, pp. 372–373. See also Panait, p. 179

- ^ Holban et al., p. 335; Al. A. Vasilescu, pp. 372–373

- ^ Panait, p. 179. See also Iorga (1902), p. lxxvi

- ^ Panait, pp. 179–180

- ^ Iorga (1902), pp. lxxvi–lxxvii. See also Iorga (1917), p. 1131

- ^ Panait, p. 180

- ^ Holban et al., p. 335; Al. A. Vasilescu, p. 373

- ^ Besse, p. 22

- ^ Giurescu, p. 382

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxxvii

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. lxxvii. See also Dobrincu, pp. 201–202

- ^ Samarian, p. 259

- ^ Dobrincu, pp. 201–202

- ^ Dobrincu, pp. 214–215

- ^ Andrei Veress, "Păstoritul ardelenilor în Moldova și Țara Românească (până la 1821)", in Analele Academiei Române. Memoriile Secțiunii Istorice, Vol. VII, 1927, p. 172

- ^ Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou & Mircea, pp. 291–292

- ^ Dobrincu, p. 202

- ^ Păun, pp. 122–123

- ^ Păun, p. 122

- ^ Samarian, pp. 130–131

- ^ Papadopol-Calimah, p. 397

- ^ Iftimi, pp. 33, 45–46

- ^ Papadopol-Calimah, p. 402

- ^ Păun, pp. 124, 128

- ^ Iorga (1930), pp. xiv, 170

- ^ Louis Roman, "Populația Basarabiei în secolul XIX: structura națională", in Studii și Articole de Istorie, Vol. LXII, 1995, p. 44

- ^ Holban et al., p. 425

- ^ Constanța Vintilă, "Secretarii străini ai domnilor fanarioți. Rețele și patronaj în secolul al XVIII-lea", in Revista Istorică, Vol. XXXIII, Issues 4–6, July–December 2022, pp. 253–255

- ^ Holban et al., p. 22

- ^ Holban et al., pp. 362–365

- ^ Holban et al., pp. 364–366

- ^ Holban et al., pp. 370–371

- ^ Holban et al., pp. 366–367, 371

- ^ Giurescu, pp. 381, 382–383

- ^ Iorga (1902), pp. lxxvix, lxxix. See also Chițulescu, p. 181

- ^ Iorga (1917), pp. 1135, 1137; Papadopol-Calimah, p. 397

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. xci

- ^ a b V. Mihordea, "Cronica istorică. Mărunțișuri istorice", in Curentul, 22 November 1936, pp. 1–2

- ^ Iorga (1902), p. xci

- ^ Brătianu, pp. 351, 358–363; Holban et al., p. 392

- ^ Brătianu, pp. 358–363

- ^ Brătianu, pp. 360–362

- ^ Brătianu, pp. 351, 363

- ^ Iorga (1930), pp. xiv, 171

- ^ Rizo-Rangabé, p. 49

- ^ Vasile Panopol, "O lume apusă. Pe ulițele Eșului", in Contemporanul, Issue 5/1994, p. 7

- ^ Rizo-Rangabé, p. 49

References

- Colette Axentie, "Date istorice despre Spitalul Pantelimon (1735—1900)", in Revista Monumentelor Istorice, Issue 1/1992, pp. 92–96.

- Jean-Paul Besse, "La pastorale dans l'Orient orthodoxe. Aux VIIe et XVIIIe siècles", in Le Messager Orthodoxe, Vol. IV, Issue 81, October 1978, pp. 17–48.

- Gheorghe I. Brătianu, "Les observations de M. de Peyssonnel en 1777 sur l'exécution du traité de Koutchouk-Kaïnardji", in Revue Historique du Sud-Est Européen, Vol. VI, Issues 10–12, October–December 1929, pp. 339–363.

- Jean-Louis Carra (contributors: Friedrich Wilhelm Bauer, Veronica Grecu, Ligia Livadă-Cadeschi), Istoria Moldovei și a Țării Românești. Iași: Institutul European, 2011. ISBN 978-973-611-609-4

- Policarp Chițulescu, "Cărturari, librari, editori. Crâmpeie din viața boierilor Văcărești. Însemnări autobiografice inedite ale lui Ianache Văcărescu și ale fiului său, Nicolae", in Revista Istorică, Vol. XXXII, Issues 1–3, January–June 2021, pp. 179–185.

- Gheorghe Diaconu, "Relațiile Patriarhiei de Antiohia cu Țările Române și închinarea Mănăstirii Sfântul Nicolae Domnesc Popăuți (I)", in Teologie și Viață, Vol. XXVI, 2016, pp. 150–191.

- Dorin Dobrincu, "Privilegii fiscale în Moldova epocii fanariote (I)", in Suceava. Anuarul Muzeului Național al Bucovinei, Vols. XXIV–XXV, 1997–1998, pp. 199–216.

- Constantin C. Giurescu, "Rectificări și precizări la cronologia domniilor fanariote", in Revista Istorică Română, Vol. X, 1940, pp. 379–384.

- Maria Holban et al., Călători străini despre Țările Române, Vol. IX. Bucharest: Editura Academiei, 1997. ISBN 973-27-0566-3

- Sorin Iftimi, Cercetări privitoare la istoria bisericilor ieșene: monumente, ctitorii, mentalități. Iași: Doxologia, 2014. ISBN 978-606-666-122-5

- Nicolae Iorga,

- "Prefața", in Documente privitoare la familia Callimachi, Vol. I, pp. vi–ccxiii. Bucharest: Institutul de Arte Grafice și Editură Minerva, 1902.

- Documente privitoare la Istoria Românilor culese de Eudoxiu de Hurmuzaki. Vol. XIV: Documente Grecești privitoare la Istoria Românilor. Partea II: 1716–1777. Bucharest: Ministry of Religious Affairs, 1917 [sic].

- Domnii români după portrete și fresce contemporane. Sibiu: Historical Monuments Commission & Kraft Publishers, 1930.

- Maria Nystazopoulou-Pelekidou, I. R. Mircea, "Τὰ Ρουμανικὰ ἔγγραφα τοῦ Ἀρχείου τῆς ἐν Πάτμῳ Μονῆς", in Byzantina Symmeikta, Vol. 2, 1970, pp. 255–327.

- Panait I. Panait, "'Tot norodul Bucureștilor' în lupta pentru dreptate socială și libertatea patriei (sec. al XVIII-lea)", in Muzeul Național, Vol. VII, 1983, pp. 177–183.

- Alexandru Papadopol-Calimah, "Amintiri despre Curtea Domnească din Iași (II)", in Convorbiri Literare, Vol. XVIII, Issue 10, January 1885, pp. 393–411.

- Radu G. Păun, "Solidarități și idealuri în veacul al XVIII-lea românesc. Mărturia ctitoriilor domnești", in Sud-Estul și Contextul European. Buletin al Institutului de Studii Sud-Est Europene, Vol. IX, 1998, pp. 120–130.

- Eugène Rizo-Rangabé, Livre d'or de la noblesse phanariote en Grèce, en Roumanie, en Russie et en Turquie. Athens: S. C. Vlastos, 1892. OCLC 253885075

- Pompei Gh. Samarian, Medicina și Farmacia în Trecutul Românesc 1382–1775. Călărași: Tipografia Moderna, [n. y.].

- Tereza Sinigalia, "Studii și cercetări. Un program arhitectural din moștenirea brâncovenească destinat 'zăbavei și plimbării'", in Revista Monumentelor Istorice, Issues 1–2/1998, pp. 5–17.

- Al. A. Vasilescu, "Cronologia tabelară. Data alcătuirii și autorul ei", in Revista Istorică Română, Vol. II, 1932, pp. 367–381.

- Matei D. Vlad, "Politica internă și externă a domnitorului Grigore al II-lea Ghica", in Revista de Istorie, Vol. 38, Issue 10, October 1985, pp. 987–1003.