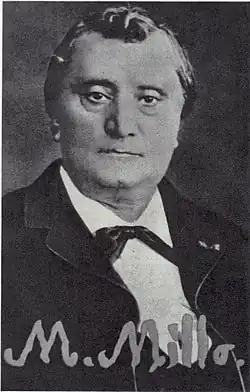

Matei Millo

Matei Millo | |

|---|---|

Signed photograph of Millo in old age | |

| Born | November 24/25, 1813 or 1814 |

| Died | September 9, 1896 (aged 81–82) |

| Alma mater | Academia Mihăileană |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, singer-songwriter, dramatist, librettist, theater director, manager, producer, poet |

| Years active | 1834–1895 |

| Movement | |

Matei or Mateiu Millo (also Milo or Milu; Romanian pronunciation: [maˈtej miˈlo]; November 24/25, 1813 or 1814 – September 9, 1896) was a Moldavian, later Romanian stage actor, singer, producer and playwright, noted as a founding figure in local theater. Hailing from two lineages of boyar aristocrats (one of which was originally French), he appeared in amateur productions around the age of twenty, alongside Vasile Alecsandri—who, later in life, was Millo's main literary backer. Violently shunned by his parents for what was seen as a lowly profession, he spent some time in Paris, possibly studying acting, and experienced there a form of material destitution that would plague him throughout his career. He returned to a position as art director of Moldavia's National Theater in Iași, pushing through an agenda of subversive Romanian nationalism, then playing some part in the liberal uprising of 1848. Late that year, Millo created an all-Romanian sensation by writing, producing, and starring in the first local operetta, Baba Hârca. His performances in travesti, and his penchant for naturalness, became hugely popular with theatergoers of all classes. They prompted Alecsandri to use Millo for a long series of Coana Chirița comedies.

Touring all Romanian-inhabited provinces, which at the time straddled three empires, Millo settled in Wallachia during 1852; he took charge of the Grand Theater in Bucharest, while also teaching at the Conservatory, and involved himself in the effort toward Moldo–Wallachian unification. He was a high-ranking Freemason, and as such involved in political intrigues before and during the creation of a Romanian Principality. Millo had renounced his boyar title and had championed the common folk, but, finding himself challenged by younger professionals such as Mihail Pascaly, fell back on conservative elitism. His conflict with Pascaly grew into a clash of philosophies and acting styles, particularly since his rival questioned the moral qualities of Millo's plays and revues. The aging Millo continuously promoted himself, including by having publicity images of himself taken by Carol Szathmari, or by claiming to be fighting government censorship. He was pushed into near-bankruptcy by his quarrels and the disdain of the Westernized theatergoers, though he still registered moral victories and gained an international following.

Millo's return to nationalist propaganda after the Romanian war of independence, and subsequently reconciled with Pascaly—whom he eventually outlived. He remained unchallenged in the post-1881 Kingdom of Romania, which awarded him some high distinctions, and was upheld as a good example by the influential group of writers at Junimea. He was by then indigent, and only drew serious revenue from continuously touring. His physical decline visible to his audience, Millo died in 1896, shortly after one final performance at Iași—leaving a trove of unpublished manuscripts. While he did not receive formal accolades during the first half of the 20th century, he had some of his plays continuously performed; he was the object of a public cult under the communist regime, which regarded him as a critic of previous administrations. He endures in cultural memory mainly for having helped to limit the spread of neo-romanticism, and for having introduced his country to theatrical realism.

Biography

Origins and debut

Millo is conventionally argued to have been born on the night of November 24–25, 1814,[1] though he preferred November 24, "just before Saint Catherine's", as his official birthday; he also mentioned having been a premature baby.[2] While he himself did not indicate the year, his biographer Ioan Massoff hypothesized that it was likely 1813,[3] which is also used by writer Mihail Sadoveanu.[4] His parents were Vasile Millo and Zamfira née Prăjescu, and his grandfather was the poet Matei Milu.[1][5] The family practiced Eastern Orthodoxy, as subjects of the Moldavian Metropolis. Matei Jr had several sisters, who became nuns at Agapia and Văratec;[6] he also had a brother, Alecu.[7] Early newspaper reports have the actor as a native of Spătărești, in Suceava County (close to the town of Fălticeni, where his cousin, also known as Matei Millo, was Mayor),[8] while Sadoveanu believes that Millo was born at Iași, the Moldavian capital, on what was already known as "Millo Street" (since his parents owned property there).[9] Later biographies contrarily settle on the village of Stolniceni-Prăjescu, in Iași County,[1][10][11] also rendered as "Stolnicești" in some accounts.[12]

The actor's paternal ancestors were French and Greek, active in the Danubian Principalities (Moldavia and Wallachia) when these were still tributary states of the Ottoman Empire. His great-grandfather on that side was Jean Mille, who had worked as a Dragoman in 18th-century Moldavia before being raised into the local boyardom, and naturalized as "Enachache Mille".[13] Matei's Moldavian mother belonged to a more ancient boyar clan,[14] first attested in the 16th century.[15] She had family on both sides of the new border with the Russian Empire, which in 1812 had annexed the principality's eastern half, organizing it as the "Bessarabia Governorate". Zamfira thus owned a Bessarabian estate at Stăuceni.[16]

Always regarded as a member of the boyar class,[17] young Matei was first educated by private tutors at Spătărești. As assessed by Sadoveanu, such schooling came late in childhood and was "rather superficial."[18] He was later sent to Victor Quinem's boarding school in Iași. Though he only attended from 1833 to 1834,[1] he became proficient in French, the language of instruction.[19] He is believed to have debuted as an actor in April 1834, when he appeared in an amateur staging of Gheorghe Asachi's Serbarea Păstorilor Moldoveni. The show was honoring Pavel Kiselyov, who had been Russian overseer in the Danubian Principalities; Millo shared the stage with three future writers and politicians: Vasile Alecsandri, Costache Negri, Mihail Kogălniceanu[20] (they all had parts in travesti, as girls).[21] Millo alone drew praise from Moldavia's ruling Prince, Mihail Sturdza, who awarded him an engraved and gilded pocket watch.[22] At least one manuscript of a play by Millo, called Sărbare ostășască, dates back to 1834—and was intended as an homage for Prince Sturdza's birthday.[23] His formal debut as an author was with the play Un poet romantic, published in 1850[1][24] but dated by Sadoveanu to 1835.[25] It constitutes a study of the conflict between the old society and the newer ideas brought in by Romanticism. Although performed at various intervals, it was never actually given a finishing touch, and is regarded by Negruzzi as an incomplete work.[26]

Millo's embrace of acting was viewed as an embarrassment by his relatives, who once had him beat up in public in hopes of persuading him to reconsider.[27] The young man was enrolled at the princely college, Academia Mihăileană, from 1835 to 1836.[1] According to Sadoveanu, in 1835 he completed and staged two other plays, namely Postelnicul Sandu Curcă and Piatra Teiului. The latter, a musical with contributions by Elena Asachi, was performed for Sturdza at a manor in Horodniceni; it also marked Millo's much-lauded debut as a singer.[28] In November 1840, Millo, having already left his family home,[29] informed his father that he was leaving for Paris, in the Kingdom of France, together with a boyar friend, Nicu Mavrocordat. They only arrived at their destination in January of the following year.[30] Living there to 1845, and mysteriously spelling his surname as "Millot",[31] he studied theater, took private lessons, followed the great actors of the day (Frédérick Lemaître, François Jules Edmond Got, Hugues Bouffé, Pierre-Alfred Ravel) and probably played minor roles with French troupes.[1] Sadoveanu believes that he was also employed at the Théâtre du Vaudeville.[32]

Vasile Millo had died in 1841, leaving Matei's maternal uncle, Iancu Prăjescu, as his children's main caretaker. In a review of their correspondence, genealogist Arthur Gorovei observed that Millo was explaining his studies of dramatic art as a valid career choice, since, upon his return to Moldavia, he could be assigned a state salaried job in that field; he was purposefully vague or "fantasizing", sometimes presenting himself as a student of engineering.[33] Literary historian Claudia Dimiu suggests that Millo had claimed to be specializing in "political economy", and was receiving his stipend on a promise that he would graduate in that field.[34] His protector was a distant relative, Ortansa the Countess Fallaux, who was also the object of his affection, and possibly his lover.[35] Millo spent the entirety of his income and, at some point before August 1844, did time in the debtors' prison. To escape re-incarceration, he asked Prăjescu to send him large sums, threatening suicide. He promised to return home on repeated occasions, but complained that the money went toward curing his erysipelas.[36]

First successes

Millo's passion for acting continued to annoy his aristocratic relatives, who were only placated when they obtained him employment as art director of the Iași National Theater, where he began serving on February 15, 1846.[37] He shared the attributes of his office with Nicolae Șuțu, who had earned respect as a political writer.[38][39] Their management was immediately criticized by a group of Romanian nationalists, including Nicolae Istrati, who objected that the first play taken up in production was an adaptation of Clarissa, done with an all-French troupe of actors. Millo was affected by this reaction, and commissioned Asachi to write a Moldavian-themed play that could satisfy the public.[38] Șuțu withdrew from the enterprise soon after, and Millo took over as the more senior manager, supervising Victor Boireaux Delmary, who had been called in to handle French-language productions.[40] He also employed Alexandru Flechtenmacher as a bandmaster.[41] Now legally emancipated, in March 1846 Millo started a dispute with Prăjescu over the remainder of his estate; it emerged at the time that he had single-handedly spent most of the family income, including all revenue produced by the estates of Spătărești and Stăuceni, on his personal expenses in Paris.[42] Spătărești went to Matei's brother.[43]

Upon his return from Paris, Millo reportedly brought in a "case filled with plays, roles, wigs, costumes, makeup and many other of the minuscule tools of the theatrical art".[27] He himself performed only occasionally, as an unpaid amateur—critic Iacob Negruzzi reports seeing him in 1847, when the Iași troupe organized a benefit show for survivors of the great fire which had ravaged the Wallachian capital, Bucharest.[44] Various scholars read such performances as already professional, and indicate his debut as occurring even earlier, on March 1, 1847.[45] He explored taboos, and riled up boyars in the audience, with the piece Mulatrul. This work indirectly referred to the fate of Romanies (Gypsies), most of whom were slaves of the boyars, by having them compared to Black slaves in the US.[27][38] Mulatrul was performed in October 1847, and resulted in the National Theater being closed down by Prince Sturdza; Millo lost his position to the more obedient B. Luzzatti, and was retained only as an actor and stage director.[38] In 1848, he returned as Chir Găitanis in Alecsandri's comedy, Nuntă țărănească; the production generated publicity by having boyaresses appear in traditional peasant clothes.[46]

One contemporary account, by Andrieș Bașotă, informs that Millo conspired with other youths, including Kogălniceanu, Negri, and Alecsandri, in fomenting the liberal uprising of March 1848; surrounded in Alecu Mavrocordat's home by the Sturdza loyalists, he only narrowly managed to evade arrest.[47] As noted by actor Mihail Belador, Millo himself had embraced nationalism, and, after the abortive revolution, found ways around state censorship for the circulation of national ideas.[48] He opened in December 1848 with his own comédie en vaudevilles, Nișcorescu, which was a major hit. According to Sadoveanu, it broke with the traditions inaugurated by Costache Caragiale—in that it no longer relied on overacted renditions of texts by Caragiale and Costache Aristia, and had embraced modern tastes.[49] Also that month, Millo followed up with Baba Hârca, set to Flechtenmacher's melodies and largely inspired by tales of Gypsy witchcraft.[50] It is remembered as the first-ever Romanian operetta.[11][51] He appeared as the titular character, in travesti as a Romani hag; his performance and the text, which used accessible Romanian, drew in crowds from all across town, unusually including members of the lower classes.[52] The songs in particular were widely circulated after being published in Anton Pann's sheet music collection, Spitalul amorului.[53] However, ethnographer Ioan Pop-Curșeu argues that the play was essentially supportive of racial and class segregation, its message amounting to: "it does not do for Gypsies to go against a nobleman."[54]

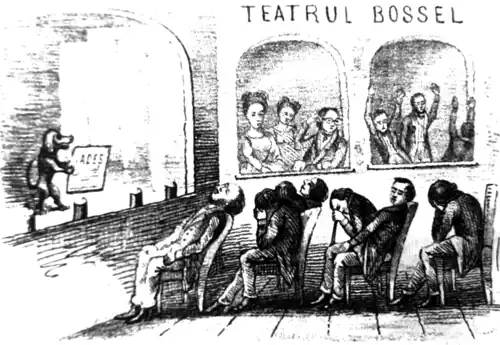

Millo was selected by Alecsandri to star as Coana Chirița, another travesti act, in a series of highly successful comedies, which Millo also produced and premiered. His performance was widely regarded as a masterclass in visual humor, since the audience habitually burst out laughing before he had recited his first line.[55] In 1850, despite renewed anger from his family and fellow boyars, Millo opted to turn professional,[56] and proceeded to tour the Moldavian and Wallachian towns.[57] Upon crossing the border at the Milcov, he was retained for a while. Some accounts suggest that he was being persecuted by the Moldavian authorities, possibly instigated by rival actors from Wallachia,[58] who refused to stamp his passport until reported on by indignant newspapers.[59] He had taken with him his entire troupe, including future celebrities such as Neculai Luchian and Elena Theodorini. As they waited to be allowed their crossing, they improvised a theater from one of Focșani's trading-posts, and staged subversive, "national" plays for a delighted audience.[60][61] Millo then took Coana Chirița to Bucharest's Bossel Hall, premiering it on August 5, 1850. This performance was the first in Wallachia's history to require three encores.[62] Beginning in 1851,[1] Millo staged numerous performances for the Romanians living under Imperial Austrian rule in Transylvania and Bukovina—as noted by writer Camil Baltazar, he effectively established a "cultural embassy" to these territories.[27] Some Bessarabians also report that Millo and his troupe came to Kishinev c. 1850, though no contemporary trace of this has been found.[63]

Millo was much loved by the Romanian-speaking public for his repertoire, in which Alecsandri's comedies featured most prominently, and for his playing style, comically realist, with touches of gravity.[1] As Negruzzi notes, his contribution in this area saw him appearing as "original types from all our social classes".[64] He was by then the only producer whom Alecsandri still agreed to work with,[65] but also staged French comedies translated by the Countess Fallaux.[35] He was also experimenting as a lyrical poet, albeit less known in the field: in 1851, he produced a romantic piece dedicated to Neamț Citadel; it survived in a copy made by Alecsandri, who much admired it.[66] Finding solidarity with his more destitute spectators, Millo openly renounced all claims to a boyar's title and privilege.[67]

Bucharest relocation

Millo organized theater in both principalities—he was at Iași until 1852, and then moved to Wallachia.[1][48] Sadoveanu, who dates this to 1854, believes that Millo was insulted when the Moldavians switched to Italian opera, after Delmary had successfully signed up his own professional troupe of singers.[68] Millo was also presumably trying to run away from his outstanding debts at Iași.[69] He was reportedly invited to Bucharest by the reigning Prince, Barbu Dimitrie Știrbei, who had enjoyed Baba Hârca,[70] and who wanted him personally as chairman of the Grand Theater.[48] According to various accounts, Știrbei and his son-in-law, Alexandru Plagino, had had a decisive role in getting Millo and his troupe permission to leave Focșani.[71] However, the monarch had set property requirements for any person applying for the managerial position, which created a problem for Millo, who was not solvable. He therefore had to be vouched for by another protector, Captain D. Budișteanu.[72]

Upon inaugurating his term at the Grand Theater, Millo exposed Costache Halepliu, his former assistant at Iași, for having stolen Baba Hârca and other plays, without crediting or paying the author. Within three years, Știrbei had rejected Halepliu's application for performing in Wallachia.[73] Millo began producing plays by Alecsandri, helping to unify the cultural scene,[48][72] and, as noted by poet Grigore Alexandrescu, focused his jibes mainly at Wallachia's own "privileged class."[21] However, he was again running out of money, and could no longer afford to produce new plays; the company was effectively run by Budișteanu, who collected on his debt.[72] Grudgingly reunited with his rival C. Caragiale, Millo was imprudently acting as Caragiale's superior. Caragiale took his revenge in autumn, when Știrbei's son-in-law (and Millo's protector) Alexandru Plagino was away on business; Millo was unceremoniously fired in autumn 1853, and had to build up a private troupe, alongside the more junior actor Costache Mihăileanu.[74] Millo was swiftly reemployed by Plagino in October 1854, with a contrast that lasted into 1859—when C. A. Rosetti took over.[75]

From his position in Bucharest, Millo witnessed the campaigns for a Moldo–Wallachian union. He supported this move, including through his induction into the local Freemasonry—around 1856, he was initiated into Auguste Carance's lodge, Steaua Dunăreană, which only received Frenchmen or their descendants, and which allegedly conspired to have Lucien Murat placed on the envisaged unified-Romanian throne.[76] The proceeds from one of his shows were publicly advertised as "for the Freemasonry's benefit".[77] According to scholar Georgeta Țurcanu, Millo allowed the unionist agenda to seep into his theatrical program, while tolerating explicit nationalist propaganda by his employee, Alexandru Evolschi.[78] He also allowed other activists to spread out their pamphlets directly to the audience.[27]

In 1856, Alexandru Ghica took over for Știrbei at the head of a regency, or Căimăcămie. Its stringent censorship laws only stimulated Millo, who is said to have loved the challenge.[72] In December 1858, the nationalist intellectual Ion Ghica, who resented his relative the regent, went to see a production of a Millo play, Prăpăstiile Bucureștilor, with Millo himself in the central role. He found it to be "horrible" overall, but also attuned to the revolutionary atmosphere that was prevailing in Wallachia, and reviving the ideals of 1848.[79] Prăpăstiile Bucureștilor was nominally an adaption of Roger de Beauvoir's Les Enfers de Paris, but featured Romanian nationalist messages throughout.[61] One of the songs performed therein advised Wallachians and Oltenians to form a closer bond with their Moldavian brethren, and to elect a "good shepherd" for the resulting "flock".[80] The text is overall slightly anti-Greek, displaying the more conservative and avaricious elements as Hellenized and diglossic (he would apply the same recipe in various later texts).[81] In showcasing his own nationalism, Millo also wrote and performed a patriotic play about Stephen the Great.[61] Other such propaganda texts by his own hand are known to have existed, but were lost before publication.[82]

The union process and elections held in January 1859 eventually propelled a Moldavian, Alexandru Ioan Cuza, to the position of Domnitor over a federated Principality of Romania, with its capital in Bucharest. Millo composed a hymn for the occasion, publishing it in Românul newspaper and singing it in front of Cuza,[83] to music composed by Ioan Andrei Wachmann.[61] Millo then held a celebratory speech as the Domnitor established a Bucharest Conservatory.[84] Around 1860, Millo was apparently networking on cultural matters with the radical anti-unionist Istrati, possibly staging one of his musicals at the Istrati manor in Rotopănești.[85] Informal recognition came in 1863, when Millo was made a Venerable (or "First Overseer")[77] of Carance's new lodge, Înțelepții din Heliopolis, which carried on, with interruptions, into the 1870s.[86] Millo had been kept on by the Rosetti as a permanent employee of the Grand Theater (now called "National Theater"), but still had to share a stage with C. Caragiale. This period also witnessed the start of his conflicts with the younger Mihail Pascaly: though the two men had appeared in several acclaimed productions, Millo, who preserved some administrative attributions, cut off Pascaly's pay, causing the latter to quit and leave for Iași.[87] The actor's old friend, Mihail Kogălniceanu, took over as Minister of Culture, and only confirmed Știrbei and Rosetti's stances in regard to Millo—against increasingly publicized attempts by Pascaly to have Millo removed.[88]

At the time, anti-Cuzists on the left and right had formed a "monstrous coalition". As observed by journalist Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu in late 1863, Millo was shying away from staging Alecsandri's Zgârcitul risipitor, which was too mordant in its anti-boyar satire (and as such could risk upsetting the emerging establishment), and also claimed that he was censoring Caragiale—tenured by his company, but never allowed to take the stage.[89] The same author contented, in February 1864, that Millo was a disappointment, and seemingly "accursed", since he could no longer satisfy popular demands, and since his entire method seemed to rely on copying an Italian model. Hasdeu stated his belief that Millo was being controlled by the state-appointed dramaturge, Ion Strat, an exponent of the "fattened class".[90] From 1864 to 1866, Millo taught at the Conservatory,[1] while establishing an associated artists' troupe, which he led together with Ghica and Constantin Dimitriade.[48][91] In 1865, the Legislative Bodies unanimously voted to grant Millo a monthly salary of 600 French francs.[48] Over the mid-1860s, Carence and Millo became opponents of Cuza; in early 1866, the coalition, backed by their lodge, succeeded in removing Cuza, replaced with Carol of Hohenzollern.[77]

Triumph

During the Cuza years, Millo had befriended the photographer Carol Szathmari. In 1866, Szathmari worked as a stage designer for one of his shows, producing optical illusions of ghosts.[92] A while after, Millo employed the same artist for a set of publicity photographs, copied into oil paintings by Craiova's Nicolae Elliescu. The first such works in Romanian advertising history, they were meant to showcase his range—in costume as an old boyar from Prăpăstiile Bucureștilor, as a peasant, as Marguerite Gautier, and as the Jewish Herșcu.[93] Pascaly stayed out of the effort to unify troupes, which was itself eventually brought down by Dimitriade's financially unsound investments. In 1867, Millo and Pascaly's troupes fused into a single group, though they each continued to perform in distinct parts of the country. Millo and Pascaly appeared together in a production of Henri Murger's Bonhomme jadis; the split became inevitable, and by 1870 Millo was again running his own self-titled company.[94]

In addition to his performances, Millo wrote a number of translations, local adaptations (including a version of Le Bourgeois gentilhomme)[95] and original plays, helping fill gaps in the scanty Romanian theatrical repertoire of the time. His published volumes of that time include Baba Hârca (1851) and Masca pe obraz sau Hai să râdem (1862).[1] In 1863, he arranged for the stage a new historical play by his actor Ion Anestin, which detailed events from the life of a hajduk leader, Iancu Jianu. Especially after 1877, he made sweeping changes to the original text, to the point where he is credited as its co-author.[96] Millo's work with Alecsandri allowed him to borrow heavily from the latter's "reservoir" of characters, in his own comedies,[97] and "obtained a franchise on the character Chirița, so as to write [his own] 'trifles' while on tour".[98] He eventually published his own Coana Chirița play, which places her at the 1873 Vienna World's Fair.[99] Philologist Andrei Nestorescu notes that all these works are remarkably suited to the taste of his intended readers, and that Millo deserves praise for being able to write on the go, at a "downright exhausting" pace, without steady revenue from a farm or other independent businesses.[100]

In old age, Millo found himself challenged by a group of young men in the theatrical business, including Pascaly and Ion Luca Caragiale. Both derided Millo for employing a troupe of mediocre actors, who could never upstage him; the Pascaly–Millo conflict grew into one of social class, with Millo now seeing himself as a member of the upper classes, challenged by an impudent commoner.[101] Baltazar defends Millo, noting that his habit of working with amateurs had cultivated new talents in acting and writing, including Mihai Eminescu (briefly employed as Millo's prompter in 1868) and actor Grigore Manolescu.[27] Millo himself tried to objectify his increasing disdain by suggesting that Pascaly was protecting his own passion for melodramas—this claim was later dismissed as unfair by Paul Gusty, the theater director.[102]

In 1870, Millo adapted and staged Honoré de Balzac's Mercadet, as Moftureanu financiar. On its premiere, he surprised his audience with a creative plea for money, likening himself to the play's protagonist.[103] Millo's most celebrated tour outside Romania came that same year, when he visited with the Romanian communities of Austria-Hungary. On one hand, his staging of "national" plays fascinated intellectuals such as Iosif Vulcan, who took him as an example; on the other, he could reach out to Hungarians as well, and was invited to perform at the Magyar National Theater in Kolozsvár.[104] Also then, chairmanship of Iași's National Theater went to Neculai Luchian. During his time there, he accepted some of Pascaly's artistic notions, but ignored his depiction of Millo and Alecsandri as literary corrupters—he therefore allowed the company to stage its own versions of Millo's plays.[105] Luchian's implicit program of stylistic unification was favored by Eminescu, now active as a theater columnist.[106] Pascaly, who emerged as chairman of Bucharest's National Theater in 1871 (against vocal protests by Millo), tried to appease his rival with an open letter, inviting him to rejoin the troupe. Millo snubbed him, causing Pascaly to retort that there was after all no place on the state-run company for "canzonettas".[107] In retaliation, Millo rented out Bossel Hall, which was located opposite of Pascaly's national venue. He announced to the public that he was premiering a topical canzonetta, which he only wrote after his tickets had been sold out—and then performed to uproarious laughter.[27]

Around 1872, Millo welcomed to Romania the Émilie Keller troupe, which was on an international tour, and performed alongside its actors in their native French.[108] In 1874, with the Ministry of Culture overseen by Alecsandri's political ally, Titu Maiorescu, he could return to high favor. He joined the National Theater's section for dramaturges, while Pascaly was sidelined.[109] Though a personal friend of Prime Minister Lascăr Catargiu,[27] he still mocked figures of the right-leaning regime, going as far up as Domnitor Carol. His Apele de la Văcărești, published in 1872,[1][110] is supposedly the first Romanian revue; its subject matter was drawn from life, exposing the monarch and his ministers for having sought to commercially exploit thermal waters found at Văcărești.[27] It was shown at Bossel's, but its text was constantly changing to include more topical jokes.[111] It nevertheless failed to impress the public.[110] Millo experienced a slump when his troupe was performing both at Bossel and inside the Bucharest Circus—his ticket sales were below his estimations.[112]

Millo had become a difficult man to work with, engaging in public feuds with the entire Caragiale family, as well as Flechtenmacher's wife Maria, but managed to regain his "immense popularity" with the common folk, who "filled up the theatrical hall" whenever one of his shows was presented.[113] Dimiu suggests that such efforts required concessions to bad taste, since Millo, who was "past his prime", understood that any more serious theatergoers would no longer be in the audience.[114] As Negruzzi writes, "Millo was wrong not to have stepped down from the stage when it was time to do so, and so in the last twenty years of his life he no longer resembled the great actor he once was."[115] He still had his upper-class defenders, including Alecsandri. In 1875, the latter wrote a short preface to his own collected works, in which he suggested that he and Millo had managed to elevate the Romanian theatrical enterprise as a whole. As noted a century later by scholar Ion Roman, the "apparently presumptuous" claim was overall accurate, since Alecsandri was still unchallenged as a dramatist—including by Millo's texts, which were "modest".[116] Some two years after Alecsandri's verdict, Ioan Slavici, who contributed to Maiorescu's Junimea society, declared that Millo stood for Romanian theater, while Pascaly was busy toadying the French.[117] Millo had by then transgressed against his Junimist supporters by agreeing to showcase and co-author the anti-Junimea revue Cer cuvântul.[111]

-

As the boyar in Prăpăstiile Bucureștiului

As the boyar in Prăpăstiile Bucureștiului -

-

In travesti as Marguerite Gautier

In travesti as Marguerite Gautier -

As Barbu the lăutar

As Barbu the lăutar -

.jpg) Nicolae Elliescu's version of the Barbu picture

Nicolae Elliescu's version of the Barbu picture

Decline and death

Millo was penniless, and therefore staged his own death to receive a funeral benefit, worth some 2,000 lei; he denounced himself with the revue Millo mort, Millo viu, premiering it in July 1876.[110] In January 1877,[118] he was set to perform his political satire, Haine vechi sau zdrențe politice at the National Theater. Though mostly poking fun at Catargiu's conservative coalition, it was equally disliked by the Brătianu cabinet, which consisted of National Liberals.[110] The author himself appeared to inform the public that he had received a government order to close curtain. The spectators refused to leave, even after the candelabra had been turned off. Millo and his colleagues performed the play, to faint candlelight.[27][110][118] The resulting backlash included a motion of no confidence, though the cabinet managed to survive, with a clear majority.[110] Later in 1877, Ghica took over as general director of theaters, recruiting both Millo and Pascaly as permanent fixtures on the National Theater troupe. Millo objected that his enemy was somewhat better placed in the organizational chart, and quit to make a celebrated return at the equivalent troupe of Iași.[119]

In July 1877, when Romania had declared a war of independence against the Ottomans (part of the larger Russo–Turkish War), Millo gave benefit shows for the wounded at the Châteaux aux fleurs terrace. These had an "extremely large and fired-up audience", which included officers in the Imperial Russian Army.[120] Also then, he agreed to perform alongside Pascaly at Bucharest's Guichard Garden,[121] where the program was one of patriotic plays.[120] Driven by material want, he resumed touring the provinces, and in late 1877 reached Dorohoi.[122] As the Bucharest season opened, Millo resurfaced as stage director for the main National Theater, causing Pascaly to furiously leave for Iași.[123] For his inaugural show, Millo produced and appeared as The Jew in Alecsandri's Lipitorile satului—a play that "was overall deplorable, but with the lead actor in excellent physical and artistic form."[124] This was also noted by I. L. Caragiale, who once observed that Millo had performed "wonders" even when he had to work from a "childish text".[125] In October 1878, as the Romanian Army returned victoriously from the front, Millo was on show for the festivities, giving a performance as Barbu the lăutar.[126]

After the creation of the Romanian Kingdom in 1881, Millo was an inaugural recipient of the Bene Merenti medal, as well as a Knight of the Order of the Star of Romania.[48] Late that year, he agreed to appear alongside Pascaly in a staging of Don César de Bazan, both of them being "for long applauded and encored."[127] Shortly after, Pascaly died of an infectious disease, and Millo created a stir by not attending his funeral. He explained that he did not hold spite against ther deceased, but rather that he hated such affairs: "if it were possible, I would also skip my own funeral."[128] The recognition and monopoly he was now left with did not translate into financial success. An anecdote of the early 1880s claimed that a Greek creditor had left Brăila with a promise to shoot the delinquent actor, but then changed his mind, and lent him more money, upon witnessing first-hand his living conditions.[129] After his troupe was caught up by the 1885 floods in Botoșani, Millo asked to be saved from near-bankruptcy by city hall.[130] He received a small sum that he then used to pay for his bills at Petrino Garden.[122] When the old building of Iași's National Theater was lost to a fire, Millo spearheaded the effort to rebuild it at its current location.[11] He made another return to Iași in October 1889, with Lipitorile satului. Sadoveanu believes that he was unmatched in this role, noting that the "immense crowd" rewarded him "enthusiasm to the brink of tears".[131] Belador also gave him praise for his final appearance as a grief-stricken Barbu, done in August 1890 as an homage to the recently deceased Alecsandri.[48]

Another of Millo's own plays, called Tuzu Calicu, was never published, and had been forgotten after the author himself had withdrawn from public life;[132] "scores of manuscripts" record his satirical plays and comedic interludes, some of which are co-authored by his various colleagues.[133] In February 1890, he premiered his musical comedy Influenza at Eforiei Bathhouse.[134] He went on tour with it the following year, earning good reviews in the provincial press.[122] A final Coana Chirița comedy, showing her quarantined in Vârciorova, survives in a manuscript dated 1893.[135] Millo went on a goodbye tour in 1895, alongside the much younger Coco Demetrescu and Nicolae Soreanu. These two left anecdotes about Millo's s physical state: he could no longer remember his lines or properly hear his prompter, and he spoke with a lisp due to his toothlessness; he also had to leave the stage to relieve himself, but was still alert enough to single-handedly extinguish a fire.[136] The impoverished troupe went to Constanța, in Northern Dobruja, where they improvised a theater out of the Tomis Railway Station. Most tickets were bought by a charitable landowner, Grigore Sturdza (son of Prince Mihail) and his wife Ralu.[136]

Memoirist Rudolf Șuțu reports that Millo gave his final performance at Iași (though not his final performance ever) on March 15, 1895. He appeared for a three-act play at Tivoli Garden, where he was welcomed by local cultural activists, including A. C. Cuza (who wrote him an ode) and Xenofon Gheorghiu. According to Șuțu, he warned the enthusiastic crowd to cease applauding him, "lest I return with another performance when I'll be aged 90".[137] This account is partly contradicted by Belador and journalist Aurel Leon, both of whom report that Millo retired for good with another special feast at Iași, held in October (New Style: November) of that year.[48][138] Millo could not go through his Baba Hârca lines, but instead fell on his knees and wept profusely.[138] Some of the actor's last written letters, detailing his disease and his various financial struggles, were addressed to Eufrosina Popescu, his longtime collaborator and possible former mistress.[139] He also left memoirs, which Negruzzi demanded to see published as an "extremely precious" source of information.[140] Millo eventually died in Bucharest on September 9, 1896.[1][141] He was buried three days later in Bellu Cemetery, on a plot donated by Constantin F. Robescu, the then-Mayor of Bucharest,[8] and in close proximity to Pascaly.[142] Little is known about his family: though he was married,[11] he is believed to have had a love child, whom he himself baptized as Matei, from his 1861 fling with Popescu.[143]

Legacy

Millo's posthumous fame as a dramatist rests primarily on Baba Hârca. As Sadoveanu reports, the play is "for all its faults", "a flower in our soil." It continued to be performed with regularity, sometimes seasonally, well into the 1920s,[144] and had its popularity renewed by Ion Sava, who re-imagined it.[145] Overall, Millo's realistic approach became a Moldavian and later all-Romanian standard, to the detriment of neo-romanticism.[146] He also set the bar for Chirița performances, as these were copied by generations of actors for their "verve and humor".[11] Millo's influence was cross-cultural, as he was an indirect influence on the development of Bulgarian theater—by providing "advice and directives" to a younger colleague, Dobri Voynikov.[147] Likewise, some members of the Jewish community were directly involved in perpetuating Millo's work. His and Alecsandri's "comedic songs" were directly influential on the development of Yiddish theater, in that Abraham Goldfaden acknowledged having used them as the basis for his own comedies.[148] In 1939, the Jewish scholar Ioan Massoff penned a standard of Millo biographies, admired as such by the Romanian historian Nicolae Iorga.[149] This work also tapped into the actor's fragmentary memoirs.[150]

As observed by journalist Liviu Floda, in 1940 Millo still did not have a public sculpture in his likeness, "though he would have deserved one."[2] His name had instead been assigned to a Bucharest street, whose sign indicated inaccurate birth and death years for its namesake.[2][3] Serving as director of the Bucharest National Theater in 1946, Ion Pas staged a commemoration of Millo's death, and organized an exhibit of his various costumes and person effects.[151] Millo's image as a champion of the working classes was revived during the period of communist rule (1948–1989). The Art Institute of Iași was reorganized in late 1950 as the "Matei Millo Institute", aiming toward the "ideological, cultural and professional training of future cadres in acting."[152] The Working People's Theater of Timișoara was rebaptized after Millo in 1966,[153] but kept that name only to 1971.[154] Millo's grave at Bellu had meanwhile fallen into disrepair: before 1958, Pascaly's cross had been moved over to his rival's spot by a clerical error; Millo's older cross still existed on that site, with the added words "famous comedian".[142]

In the early 1950s, Mircea Ștefănescu wrote an eponymous play; it earned a positive review from the staff critics at Contemporanul, who commended its depiction of Millo's struggles toward a "realistic theater with a marked national and popular character" while suggesting that Millo's polemic with Pascaly, as depicted therein, was underwhelming.[155] Ștefănescu's text was nonetheless reprised at various intervals, with the title role going to either Marcel Anghelescu or Ion Finteșteanu.[156] The creation of a Romanian Television resulted in demand for sketch comedy, which took the form of anthology series directed by Alexandru Tocilescu. This segment included appearances by Octavian Cotescu as Millo, with recitations from Millo's texts.[157] An operetta called Tinerețea unui vis, which focused on Millo's struggles as a youth, was written by Nicolae Barbatescu and first performed at Iași in 1989; Leon Cordineanu appeared as the lead—his contribution is seen by critic Alexandru Vasiliu as one of the few redeeming graces of an otherwise "mediocre" show.[158]

The first posthumous edition of any play by Millo only came in 1955; a more complete one was published by Nestorescu and Liliana Botez in 1994.[159] Between these two dates, scholars had turned to analyzing Millo in his context. Nestorescu, who curated an edition of the Jianu play in 2006, proposed that he was "one of the most important 19th-century Romanian dramatists [emphasis in the original]", explaining however that his importance did not refer to his artistic worth, but to his historic role in shaping that side of Romanian literature.[160] By 2005, Mihai Lungeanu had written a radioplay called Istoria paraponisitului, which was inspired by Millo and Alecsandri's texts, and which was performed live, then recorded, at Majestic Bistro of Bucharest.[161] Millo's final Chirița play was rewritten by Cătălin Ștefănescu for a 2014 performance, then recovered by Ada Milea for a 2021 production (which adapted the titular quarantine to comment on the COVID-19 lockdowns).[98] The actor's ancestral home in Spătărești was nationalized during communism, and, in 1989, was used by the local militiaman.[11] After the Romanian Revolution of 1989, it was reclaimed by members of the Millo and Vârnav families (the latter of whom were descendants of Matei's mother-in-law); they were only granted a portion of the estate, with the house itself left in ruin.[11]

The Szathmari photographs were exhibited at the National Library of Romania in early 2015.[162] In addition to the Szathmari–Elliescu gallery of portraits, Millo's likeness was preserved in the works of various artists of his day. Constantin Lecca included Millo in a series of lithograph portraits done during the 1840s. It is seen by scholar Barbu Theodorescu as one of the most accomplished pieces of that lot.[163] A full portrait in oil, tentatively dated to 1850, was done by Niccolò Livaditti, and passed on to the Romanian Academy.[164] Posthumous depictions include one by Mircea Olarian, part of a series of historical-themed drawings.[165] In 1953, D. Stubi drew a collective portrait of Millo, C. Caragiale, and Aristizza Romanescu, which was then heliographed as a Romanian postage issue.[166] A Millo bust was placed in National Theater Museum in Bucharest at around that time, and displayed there alongside his personal items.[118] Another bust was located outside Iași's National Theater, but was removed in 1994, reportedly after credible fears that it would be stolen for scrap.[167]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Aurel Sasu (ed.), Dicționarul biografic al literaturii române, Vol. II, pp. 112–113. Pitești: Editura Paralela 45, 2004. ISBN 973-697-758-7

- ^ a b c Liviu Floda, "Cine are dreptate? Când s'a născut și când a murit Lascăr Catargiu?", in Realitatea Ilustrată, Vol. XIV, Issue 683, February 1940, p. 14

- ^ a b Ioan Massoff, "Când a murit Millo. O greșală [sic] a Municipiului București", in Adevărul, September 12, 1936, p. 2

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Iftimi et al., p. 78

- ^ Nestor Camariano, "Notițe bibliografice. Bulat T. G., 'O scrisoare dela Matei Millo către mitropolitul Veniamin Costache'", in Revista Istorică Română, Vol. XVII, Fascicles I–II, 1947, p. 186

- ^ Gorovei (1934), pp. 352–353

- ^ a b "Ultime informații", in Timpul, September 12, 1896, p. 3

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Barbu, p. 137

- ^ a b c d e f g Vasile Iancu, "Patrimoniul. Monumente care au murit sub ochii noștri, simboluri distruse. Casa Matei Millo din Spătărești – Suceava", in România Liberă, February 2, 1999, p. 16

- ^ Dimiu, p. 148

- ^ Iftimi et al., p. 78; Vintilă, pp. 252–256

- ^ Iftimi et al., p. 77

- ^ Zamfira Pungă, "Documente privitoare la familia Prăjescu în colecțiile Muzeului de Istorie a Moldovei Iași", in Ioan Neculce. Buletinul Muzeului de Istorie a Moldovei, Vol. XIX, 2013, p. 258

- ^ Gorovei (1934), pp. 352–353

- ^ Iftimi et al., p. 77; Sadoveanu, p. 355; Vintilă, p. 255

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 354

- ^ a b Al. I. Firduș, "160 de ani de teatru românesc cult. Agora unei conștiințe", in Convorbiri Literare, Issue 11/1976, p. 12

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 354

- ^ Nestorescu, p. 213

- ^ Nestorescu, p. 212

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 354

- ^ Negruzzi, p. 452

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Camil Baltazar, "Evocări. Matei Millo", in Urzica, Vol. XVI, Issue 3, February 1964, p. 5

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 354

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 354

- ^ Gorovei (1934), pp. 313–314, 322

- ^ Gorovei (1934), p. 321

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Gorovei (1934), pp. 313–320

- ^ Dimiu, p. 148. See also Iftimi et al., p. 77

- ^ a b Emil Georgescu, Vasile Bașa, "Pagini de istorie literară. O poetă franceză de origine română: Ostansa Costache Fallaux", in Cronica, Vol. X, Issue 26, June 1975, p. 8

- ^ Gorovei (1934), pp. 317–320, 324–351

- ^ Vintilă, p. 255

- ^ a b c d Valentin Silvestru, "Teatru. Creatorii teatrului național în întâmpinarea anului revoluționar", in România Literară, Issue 18/1973, p. 25

- ^ Gorovei (1934), p. 316; Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Dolinescu, p. 395

- ^ Gorovei (1934), pp. 350–353

- ^ Gorovei (1934), pp. 352–353

- ^ Negruzzi, p. 450

- ^ Dumitrescu & Dumitrescu, p. 57; Iftimi et al., p. 77

- ^ Negruzzi, pp. 450–452. See also Dimiu, p. 148

- ^ Alexandru Zub, "Din activitatea politică a lui M. Kogălniceanu la 1848", in Revista de Istorie, Vol. 29, Issue 7, July 1976, p. 1002

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Mihail Belador, "Coloana a cincea. Matei Millo. Opera, artistul (Sfîrșit)", in Evenimentul, September 19, 1896, pp. 1052–1053

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Pop-Curșeu, pp. 29–32; Nicolae Iorga, Orizonturile mele. O viață de om. Așa cum a fost, p. 94. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1976

- ^ Dolinescu, p. 396; Pop-Curșeu, p. 29

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Roman, p. xiv

- ^ Pop-Curșeu, p. 31

- ^ Dimiu, p. 148

- ^ Negruzzi, pp. 450–451

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Dumitrescu & Dumitrescu, p. 58

- ^ Mircea Radu Iacoban, "D-ale teatrului...", in Dacia Literară, Vol. XXV, Issues 128–129, 2014, p. 137

- ^ Dumitrescu & Dumitrescu, passim

- ^ a b c d Valentin Silvestru, "Teatru. Actorii in lupta pentru Unire", in România Literară, Issue 3/1984, p. 16

- ^ George Potra, Istoricul hanurilor bucureștene, p. 148. Bucharest: Editura Științifică și Enciclopedică, 1985

- ^ Ștefan Ciobanu, Cultura românească în Basarabia sub stăpânirea rusă, p. 185. Chișinău: Editura Asociației Uniunea Culturală Bisericească, 1923

- ^ Negruzzi, pp. 453–454

- ^ Dimiu, p. 145

- ^ Negruzzi, pp. 449–450

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Dimiu, p. 152; Dumitrescu & Dumitrescu, pp. 57–58

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355. See also Dimiu, p. 152

- ^ Dumitrescu & Dumitrescu, pp. 58–61

- ^ a b c d Gaby Michailescu, "Cușca suflerului. Gloriosul Național (1852–1977)", in Săptămîna, Issue 371, January 1978, p. 4

- ^ Andrei Pippidi, Andrei Pippidi, mai puțin cunoscut. Studii adunate de foștii săi elevi cu prilejul împlinirii vârstei de 70 de ani, pp. 385–386. Iași: Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, 2018. ISBN 978-606-714-449-9

- ^ Dimiu, p. 152

- ^ Dimiu, p. 152

- ^ Opaschi et al., p. 36

- ^ a b c Simion Costea, "Românii și masoneria", in Cuvântul Liber, May 29, 2002, p. 4

- ^ Țurcanu, pp. 240–241

- ^ Roman, p. viii

- ^ Țurcanu, p. 241

- ^ Brad-Chisacof, pp. 261–262

- ^ Țurcanu, p. 241

- ^ Țurcanu, p. 241

- ^ Țurcanu, p. 241

- ^ Gorovei (1940), pp. 347–350

- ^ Opaschi et al., pp. 61–62

- ^ Dimiu, pp. 152–153

- ^ Dimiu, p. 153

- ^ Hasdeu & Oprișan, pp. 16, 48, 72

- ^ Hasdeu & Oprișan, pp. 108–109

- ^ Dimiu, p. 153

- ^ Ionescu, p. 22

- ^ Ionescu, passim

- ^ Dimiu, p. 153

- ^ Negruzzi, p. 453

- ^ Nestorescu, pp. 214–215

- ^ Roman, p. xxi

- ^ a b Oana Stoica, "Rosencrantz & сo. Cum a petrecut Chirița pandemia", in Dilema Veche, Vol. XVIII, Issue 893, May 2021, p. 17

- ^ Nestorescu, p. 212

- ^ Nestorescu, pp. 211–212

- ^ Dimiu, pp. 144–145, 149–153, 156–157

- ^ Dimiu, pp. 149–152

- ^ Brăescu, p. 271

- ^ Marcea, p. 194

- ^ Barbu, pp. 136–138

- ^ Barbu, p. 138

- ^ Dimiu, p. 153

- ^ Brăescu, pp. 263–264

- ^ Dimiu, pp. 153–155

- ^ a b c d e f Șerban Cioculescu, "Breviar. Literatura în Bucureștii de altădată", in România Literară, Issue 14/1988, p. 7

- ^ a b Ioan Massoff, "Teatru. O sută de ani de teatru revuistic", in România Literară, Issue 10/1972, p. 20

- ^ Dimiu, p. 155

- ^ Dimiu, p. 148

- ^ Dimiu, pp. 157–158

- ^ Negruzzi, p. 454

- ^ Roman, p. vii

- ^ Marcea, pp. 169, 194–195

- ^ a b c S. A., "Magazin bucureștean. Vizitînd muzeele: Pagini din Istoria Teatrului Național", in Informația Bucureștiului, August 28, 1959, p. 2

- ^ Dimiu, pp. 155–156

- ^ a b Mihai Florea, "Dramaturgia Independenței", in Teatrul, Issue 10/1976, p. 19

- ^ Dimiu, p. 156

- ^ a b c Gheorghe Martiniuc, "75 de ani de la moartea marelui actor și dramaturg Millo", in Clopotul, September 8, 1971, p. 2

- ^ Dimiu, p. 156

- ^ Dimiu, p. 157

- ^ Roman, p. xxii

- ^ Aurel Duțu, "Sărbătorirea eroilor independenței la București, 8/20 octombrie 1878", in Muzeul Național, Vol. V, 1981, p. 251

- ^ Frédéric Damé, "Foița Romanului, 3 Decembre. Sĕptĕmâna teatrelor", in Romanulu, December 3, 1881, p. 1082

- ^ Paul Gusty, "Mihail Pascaly artist dramatic, 1830–1882. II", in Viața, October 3, 1942, p. 2

- ^ Alina Boboc, "D'ale teatrului'", in Luceafărul, Issue 33/2003, p. 9

- ^ "Documente ale trecutului. O petiție a lui Matei Millo", in Romînia Liberă, November 13, 1955, p. 2

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Negruzzi, p. 453

- ^ Nestorescu, p. 212

- ^ "Spectacole", in Universul, February 8 (20), 1890, p. 3

- ^ Nestorescu, pp. 212–213. See also Brad-Chisacof, p. 261

- ^ a b Ioan Massoff, "Ultimul turneu al lui Matei Millo. Teatru într'o haltă de cale ferată. — Mărinimia lui Beizadea-Vițel", in Realitatea Ilustrată, Vol. XIII, Issue 667, October 1939, p. 13

- ^ Rudolf Șuțu, "La Iași, cîndva, odată. Cu prilejul ultimei reprezentații la Iași, d. prof. A. C. Cuza a închinat versuri marelui artist Matei Millo", in Evenimentul, February 10, 1942, p. 2

- ^ a b Aurel Leon, "Bătrînețea – vîrsta însingurării...", in Monitorul, November 28, 1992, p. 2

- ^ Hațiegan, pp. 156–157

- ^ Negruzzi, p. 454

- ^ Dimiu, p. 148

- ^ a b Gheorghe G. Bezviconi, "Cimitirul Bellu din București. Muzeu de sculptură și arhitectură", in Buletinul Monumente și Muzee, Vol. I, Issue 1, 1958, p. 193

- ^ Hațiegan, p. 156

- ^ Sadoveanu, p. 355

- ^ Pop-Curșeu, p. 32

- ^ Barbu, passim; Iftimi et al., p. 77

- ^ Petre P. Panaitescu, Români și Bulgari, p. 54. Bucharest: [n. p.], 1944

- ^ Willy Moglescu, "5. Teatru. b. Teatrul evreiesc", in Nicolae Cajal, Hary Kuller (eds.), Contribuția evreilor din România la cultură și civilizație, p. 376. Bucharest: Federation of Jewish Communities of Romania, 1996

- ^ Bogdan Popa, "Anticari, librari și editori în România modernă. Familia Șaraga din Iași", in Revista Istorică, Vol. XXXII, Issues 1–3, January–June 2021, pp. 188–189

- ^ Gorovei (1940), p. 349

- ^ "Comemorarea lui Matei Millo", in Aurora, October 9, 1946, p. 2

- ^ "La Iași a luat ființă Institutul de Teatru 'Matei Millo'", in Opinia, November 11, 1950, p. 2

- ^ Doru Mareș, "Actualitate. Laboranții de pe Bega", in Observator Cultural, Vol. IX, Issue 188, October 2008, p. 13

- ^ C. D. Tomov, "TNT sărbătorește 30 de ani de... blazon. Visul unei nopți de vară, în regia Sandei Manu", in Agenda Zilei, September 26, 2001, p. 11

- ^ Nicolae Sireteanu, Eugen Luca, "Cronica dramatică. Matei Millo de Mircea Ștefănescu", in Contemporanul, Issue 42/1953, p. 2

- ^ Maria Marin, "Viitorul rol. Alexandru Drăgan", in Teatrul, Issue 7/1977, p. 61

- ^ Călin Căliman, "T. V. Antologia umorului românesc. Zîmbetul de nemurire al unor minunați actori", in Cinema, Vol. XXIII, Issue 7, July 1985, p. 18

- ^ Alexandru Vasiliu, "Cîntarea României. Premieră: Tinerețea unui vis", in Cronica, Vol. XXIV, Issue 30, July 1989, p. 3

- ^ Nestorescu, pp. 212, 213–214

- ^ Nestorescu, p. 211

- ^ Augustin Sandu, "Note. Thalia la 'Majestic'", in Luceafărul, Issue 41/2005, p. 22

- ^ Ionescu, p. 22

- ^ Barbu Theodorescu, Constantin Lecca, pp. 53, 55. Bucharest: Romanian Academy & Monitorul Oficial, 1938

- ^ Iftimi et al., p. 77

- ^ Florin Rogneanu, "Mircea Olarian monograf al Craiovei", in Ramuri, Issue 6/1990, p. 13

- ^ J. V. L., "La Bourse aux timbres. Roumanie", in Le Franc-Tireur, April 2, 1953, p. 5

- ^ Constantin Ostap, "Din scrisorile, telefoanele și audiențele zilei. Iașul nu uită paginile glorioase din istoria țării noastre", in Monitorul, September 21, 1994, p. 7A

References

- Nicolae Barbu, "Întîlniri cu Thalia. Școala ieșană de teatru", in Almanah Convorbiri Literare, 1985, pp. 136–138.

- Lia Brad-Chisacof, "Viața cuvintelor. Asupra unor grecisme", in Limba Română, Vol. 40, Issues 5–6, 1991, pp. 255–262.

- Ion Brăescu, "Dramaturgia franceză în România înainte de 23 august 1944", in Revista de Istorie și Teorie Literară, Vol. XVI, Issue 2, 1967, pp. 261–275.

- Claudia Dimiu, "Memoria teatrului. Un înaintaș plin de talent, de bune intenții și de nenoroc: Mihail Pascaly", in Teatrul Azi, Issues 11–12/2008, pp. 144–158.

- Elisabeta Dolinescu, "Muzica populară în preocupările lui Alexandru Flechtenmacher", in Revista de Etnografie și Folclor, Vol. 13, Issue 5, 1968, pp. 395–407.

- Maria Dumitrescu, Horia Dumitrescu, "Matei Millo la Focșani (1851)", in Cronica Vrancei, Vol. III, 2002, pp. 57–62.

- Arthur Gorovei,

- "Viața lui Matei Millo la Paris", in Revista Fundațiilor Regale, Vol. I, Issues 7–9, August 1934, pp. 313–353.

- "Biblioteca dela Rotopănești a lui Neculai Istrati", in Memoriile Secțiunii Literare, Vol. IX, Issue 12, 1940, pp. 347–356.

- Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu (editor: I. Oprișan), Aghiuță 1863–1864. Bucharest: Editura Vestala, 2009. ISBN 978-973-120-054-5

- Anca Hațiegan, "Femeia pe scena românească. Apariția actriței profesioniste: elevele primelor școli românești de muzică și artă dramatică (II)", in Vatra, Vol. XLVIII, Issues 562–563, January–February 2018, pp. 154–157.

- Sorin Iftimi, Corina Cimpoeșu, Marcelina Brîndușa Munteanu, Niccolo Livaditi și epoca sa (1832–1858). Artă și istorie. Iași: Palace of Culture, 2012. ISBN 978-606-93119-6-7

- Adrian-Silvan Ionescu, "Arte. Chipurile și viețile actorului", in Observator Cultural, Vol. XIV, Issue 501, February 2015, pp. 22–23.

- Pompiliu Marcea, Ioan Slavici. Timișoara: Editura Facla, 1978.

- Iacob Negruzzi, "Mateiu Millo, poet liric", in Convorbiri Literare, Vol. XXX, Issue 11, November 1896, pp. 449–454.

- Andrei Nestorescu, "Jianu, căpitan de hoți. Prefață", in Ileana Stănculescu (ed.), Texte uitate — texte regăsite, pp. 211–215. Bucharest: Romanian Academy & National Foundation for Science and Art, 2006. ISBN 973-1744-16-9

- Cătălina Opaschi, Katiușa Pârvan, Ernest Oberländer-Târnoveanu, Medalii și însemne masonice. Istorie și simbol. Catalog de expoziție. Bucharest: National Museum of History of Romania & Editura Cetatea de Scaun, 2006. ISBN 978-973-8966-10-9

- Ioan Pop-Curșeu, "The Gypsy-Witch: Social-Cultural Representations, Fascination and Fears", in Revista de Etnografie și Folclor, Issues 1–2/2014, pp. 23–45.

- Ion Roman, "Prefață. Comediile lui Vasile Alecsandri", in Vasile Alecsandri, Iașii în carnaval. Teatru, pp. v–xxiv. Bucharest: Editura Minerva, 1988.

- Mihail Sadoveanu, "Ctitorii. Matei Millo", in Universul Literar, Issue 23/1929, pp. 354–355.

- Georgeta Țurcanu, "Personalități ale vieții artistice mesagere ale ideilor social-politice în lupta pentru crearea statului român modern", in Muzeul Național, Vol. V, 1981, pp. 237–242.

- Constanța Vintilă, "Secretarii străini ai domnilor fanarioți. Rețele și patronaj în secolul al XVIII-lea", in Revista Istorică, Vol. XXXIII, Issues 4–6, July–December 2022, pp. 235–267.