Kasha (folklore)

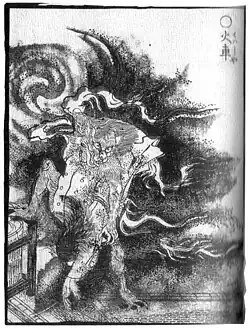

The kasha (obsolete: kwasha;[2] Japanese: 火車, lit. 'fire cart',[3] "burning chariot"[4] or 化車, 'changed wheel') in Japanese folklore is a yōkai said to steal corpses. It is now generally regarded to be a monster in cat-form, though earlier archetypes made them demon-like.

Summary

The kasha was originally neither an animal- nor man-like monster, but a fire vehicle (cf. hi no kuruma) assigned the mission of conveying the sinful to Buddhist hell.[3] The kasha as yōkai in the early modern period (16th century) was originally conceived of as the demon-like beings: gokusotsu (wardens of hell) or the Raijin thunder god.

But due to conflation with the legends of the devil-cat (nekomata) stealing cadavers, the kasha came to be seen as a cat-like yōkai in the late 17th century.[6] The famed yōkai artist Toriyama Sekien (1776) illustrated the kasha as cat (cf. § Development over time).

The kasha[a] is often said to appear with dark clouds, thunderclaps, or thunderstorms.[7]

In the regional folklore collected during the modern period, the kasha as body snatching yōkai that steal corpses from from funeral services or cemeteries are ubiquitous all over Japan.[8] Oftentimes, the kasha are recognized as monstrous cats or nekomata, sometimes said to have evolved into such form after living an extraordinarily long life[b].[8][11] At other times, the kasha is depicted much like a demon (oni) carrying the damned in a cart to hell.[12]

While some commentators flatly state that the kasha only targets the bodies of those who had accumulated evil deeds in life,[8][13][4] this is not necessarily the case, and later conceptions of the kasha as monster do not always target bodies of the villainous.[14]

There kasha also features in the folktale type Neko danka ("cat patron"), in which case the cat is not evil, but only play-acting to benefit his temple abbot master. There are similar tales in the Harima Province (now Hyōgo Prefecture).[15][16] In Makidani, Yamasaki (now Shisō, Hyōgo ), there is the tale of the "Kasha-baba".[13]

Various superstitions prescribe objects used as amulets or chanting to protect the deceased from the attack of the kasha (cf. § Prophylactic superstition).

Regional folklore

The folklore about the yōkai named kasha ("fire cart") stealing cadavers is widespread over various places across Japan,[17][8] and the wide dissemination had already occurred by the 18th century.[18][19][c][d]

In typical examples of the regional folk narrative, the kasha assumes a cat-like form, and when the deceased's body is stolen, the weight of the coffin suddenly lightens.[7] Generally the arrival of a kasha is accompanied by black clouds, thunderstorm, or fearsome wind[7][12] (as had been the case in Edo Period literature, cf. § In classics below). These great winds would be strong enough to lift the coffin into the sky, out of the hands of those bearing it on their shoulders. When this occurred, the pallbearers would explain it as the body having been “possessed by the kasha”.[22]

Examples

In the traditional funerary customs in Miyazaki Prefecture (from the time when sitting-position burials inside round barrel type coffins were common), instead of observing the usual 1–2 day wake before the funeral, a secondary wake was observed after (thus 4 days altogether), and during this tsuya wake period, someone would be left to attend the body around the clock, and close family of either gender would sleep with the body overnight in what was called yotogi[e] This stems from the superstition that the kasha would come steal the body if not on constant watch (customs of Gokase village and Miyake in Saito city).[23] And for this reason, cats were taboo during the wake, and trapped inside cages and forbidden from entering rooms.[f][23]

Allowing a cat to stride over a body causes it to turn into a monster,[g] or else result in some bad turn of events.[h] Or if a cat leaps over the corpse will stand up,[i] or revive,[j] etc. according to Miyazaki Prefecture folklore,[23] though similar lore is found elsewhere, e.g. Gunma Prefecture where it is said that a monster (kasha) leaping over the body causes the dead to revive,[k] and the approach of cats near the deceased is abhorred.[24]

A variant in Tōno, Iwate Prefecture is locally called "kyasha",[20] though it assumes the appearance of a human woman. According to the lore, when one takes the path from the village of Ayaori, Kamihei District (now part of Tōno) to the village of Miyamori (now also part of Tōno), along the mountain pass is a little mountain called Kasanokayō-yama (笠通山)[l] where she is prone to appear, looking like a woman wearing kinchaku money-bag tied to her front obi belt. She supposedly stole corpses from coffins at funerals and dug up corpses from gravesites and ate them as well.[25][26] Minamimimaki village (now part of Saku, Nagano Prefecture) is another spot where this yōkai is known as "kyasha", and as in the typical case, it was accused of stealing corpses at funerals.[27]

In the Yamagata Prefecture, a story is passed down where when a certain wealthy man died, a kasha-neko (カシャ猫) appeared before him and attempted to steal his corpse, but the head priest of Seigen-ji (清源寺) (at Hasedō, Yamagata city) drove it away. Its alleged tail was then offered to be kept at the Hase-kannon-dō pavillion (at Nan'yō, Yamagata) as a charm against evil spirits, which is open to the public on new years each year.[28]

Prophylactic superstition

Legends state that if a monk is present in the funeral procession, then the body could be reclaimed by the monk throwing a rosary at the coffin, saying a prayer, or signing their seal onto the coffin.[12]

One method of protecting corpses from kasha, in Kamikuishiki, Nishiyatsushiro District, Yamanashi Prefecture (now Fujikawaguchiko, Kōfu), at a temple that a kasha is said to live near, a funeral is performed twice, and it is said that by putting a rock inside the coffin for the first funeral, this protects the corpse from being stolen by the kasha.[29]

In Yawatahama, Ehime, Ehime prefecture, it is said that leaving a hair razor on top of the coffin would prevent the kasha from stealing the corpse.[30] In Tsumagoi village in Agatsuma District, Gunma, placing a bladed instrument (knife) on the body prevents it from becoming possessed and walking away, and similarly in Kasukawa, Seta District, Gunma a blade is said to ward against the theft of the corpse.[24]

In the custom of Himakajima island, Aichi Prefecture, placing a reed for weaving on the body, and the fine mesh supposedly defended against the kusha, an over a century-old cat,[m] from stealing the body.[n][10]

In Saigō, Higashiusuki District, Miyazaki Prefecture (now Misato), it is said that before a funeral procession, "I will not let baku feed on this"[o] or "I will not let kasha feed on this"[p] is chanted twice.[32]

In the village of Kumagaya, Atetsu District, Okayama Prefecture (now Niimi), it is said that a kasha is avoided by playing a myohachi (妙八) (percussion instrument).[33]

Cf. also the protection methods under § Toriyama Sekien.

In classics

The transition to distinctly feline-shaped kasha occurred in the late 17th to early 18th century,[34] but in the near-coeval period (early to mid-"modern"[q]) tales of the Buddhist-based vehicular kasha chariot, often driven away by high priests, did continue to appear in anthologies.[35] The depiction of kasha changed from the cart vehicle to the anthropomorphic or ogre-like gokusotsu (hell warden),[36][37][r] or other ogres such as the Raijin ("thunder god", e.g. § Echigo priest fends off) then to a cat-monster[36] (cf. § Development over time for details).

As cat

The earliest identified work depicting the kasha as cat occurs in the Kōsekishū (礦石集; pub. Genroku 6/1693) Book 1, tale 15 "Matter of cat turned kasha taking human corpse"[s], which is a story of the neko danka ("cat patron") type.[39] It tells a tale of a certain elder of the Jōdo-shū sect in Kyoto who overhears his 30 year pet cat speaking in human language at night, and the cat reveals itself to be the chief bakeneko of Kyoto. It was also the commander of cats who transform into kasha to steal the bodies when certain people die, and quarreled with the other cats that had decided to target certain noblewoman nun who was due to die the next day, as she was ill-considered and profligate, but the she was also the priest's patroness, and the priest's pet could not bear to betray its master. The pet revealed the cats' secret weakness: the Darum's juzu rosaries which could deliver mortal wounds to the monsters. The priest counseled the cat to attack full force and the priest will do his best to defend. The next day as the priest was performing the indō last rite, suddenly the clouds overshadowed, bringing thunderous rain, and as lightning was about to strike the coffin, the priest struck with his rosary, that brought back clear weather. The priest's cat returned 3 days later with his eye popped out from the injury, and was nursed but eventually died.[9][21]

Tsujidō Chōfūshi (辻堂 兆風子)'s work Tama sudare (多満寸太礼/玉すたれ; 1704), has a section on "The kasha sermon, as well as the matter of cat taking corpse",[t] which tells that when Shūgen (周厳) was abbot of Sōkō-ji (宗興寺), a Zen sect temple in Kōzuke Province (now Gunma Prefecture). One day, Shūgen heard the cats at the temple conspiring to steal the corpse of the village nanushi. The nanushi over many generations had their bodies stolen, and it turns out the nekomata were responsible. When the cats returned to his presence feigning ignorance, the abbot scolded the cats and scattered them. On the day of the funeral procession, the priest chanted his spells and lectured the cats, so that nothing untoward happened that day.[40]

Kii zōdanshū and Kanwa kii

The Kii zōdanshū and Kanwa kii also contains an episode concerning the kasha as the fire cart vehicle (Cf. hi no kuruma § Higane jizō pavilion). The anecdote below, in various versions, concerns the kasha as a monstrous being.

Echigo priest fends off

A supposedd historical event took place in the year Tenshō 2/1574 according to the Kanwa kii (漢和希夷; early modern period)[35][41] and reappears in the Kii Zōdanshū (奇異雑談集; pub. 1687)[u] under the entry entitled "Concerning how in the manor of Ueda, Echigo, at the time of funeral, a lightning cloud comes steals the corpse"[v] It writes that funeral procession was held at Ueda Manor, Echigo (now inMinamiuonuma, Niigata) a kasha made an assault attempting to steal the corpse, and nearly succeeded, but for a priest at Untō-an[w] temple who manifested his esoteric powers and protected the remains, though fainting in the process. This kasha arrived amidst heavy rain and thunder.[41]

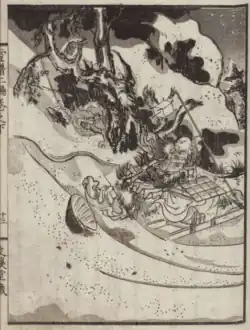

The book's woodcut illustration depicts this kasha much like the raijin (thunder god) looking like an ogre, wearing tiger's pelt loincloth and carrying a set of drums said to cause thunder (cf. image right).[42]

The emphasis of this narrative is to eulogize the deeds of the priest. The physical form of the kasha here is not discernable beyond being a black, dark cloud seeming to attack the dead (and not witnessed as a cat-monster), but since the corpse attacked was clearly not meant to be seen as an evil person, it is pointed out that the tale no longer follows the definition of the kasha as a vehicle meant to carry only the damned, and a scholar regards this as a transition evolving from vehicle to a creature-type yōkai.[35] In a later variant telling of the same tale, the identity of the kasha is changed from "dark cloud" to the monster cat nekomata[43]:

- ("Priest Hokkō" from the Hokuetsu Seppu)

In Suzuki Bokushi's Hokuetsu Seppu ("Snow stories of North Etsu Province", 1841), the heroic priest in the monster encounter of Tensho era (1574) is claimed to have been Hokkō (i.e. the historical Hokkō Zenshuku[45][35]) as the 13th abbot at the aforementioned Untō-an temple, though this has been pointed out to be anachronistic and implausible.[x] The corpse-snatcher is here the nekomata or twin-tailed cat, as aforementioned (cf. image right).[45][35] The story tells of a death in the farming village of Saburōmaru, Uonuma District, Echigo Province which lay close to the Untō-an temple. They were forced to deliver the coffin through a snowstorm which didn't subside after waiting for days. Midway in the trip, a sudden gust came, the dark clouds overshadowed the area, and a ball of fire came flying forth, enveloping the coffin. Within the fire was a twin-tailed huge cat trying to steal the coffin, but the priest Hokko used his incantations, and clubbed the monster on the head with his iron nyoi, driving it away. The blood splatter smeared the priest's kesa cloak.[y] This garment was afterwards called the "kasha-otoshi no kesa" (the kesa vestment of the one who rid/exorcised the kasha),[48][49] and still remains in the keeping of this temple.[35][20]

Inga monogatari

Two large men

In author-compiler Suzuki Shōsan's Hiragana-bon Inga monogatari (c. 1558), Book 4, Tale 5 "Matter of the woman taken by the kasha while still alive".[z] does not explicitly mention the kasha in the text (except the title), and the abductors are a pair of large men dragging the woman, but this is still given as an archetype of a kasha yōkai (not kasha vehicle) in a scholarly paper.[51]

The narrative states that in Yao, Kawachi Province (now Yao, Osaka), the wife of a certain shōya (village chief samurai) was avaricious-natured, failed to feed the servants properly, and mean to people. An acquaintance was walking on the highway one day and saw a cluster of light as if from a burning torch speeding closer. Within the light, a pair of colossal samurai-like men 8 shaku tall (2.4 metres (7.9 ft)) taking a grab-hold of both the woman's hands, and went away somewhere unknown (cf. image right). The frightened eyewitness visited the shōya to inquire, and was informed that the wife in question became ill and bedridden, dying on the 3rd day. It was said that this woman went straight to hell while still alive due to her poor conduct.[50][51]

Bad priest of Mino

In the Katakana-bon Inga monogatari (pub. Kanbun 1/1661), Book 3, Tale 11 "How a priest fallen to bad view harms self and others",[aa] the purported anecdote dated to Shōhō era (1645–1648) claims that the priest Kaishuku (快祝) of the Kaizan sect (関山派) of the Rinzai School, serving in Hachiya,[ab] Mino Province (the historical figure Kaishuku (快叔) Kaishku of Zuirin-ji) of Hachiya, Minokamo, Gifu[52]) preached there was no Buddha aside from the enlightenment he gave from his heart, and would destroy holy trees and Buddha figures, so that when he died, the kasha seized his body and took it away. This narrative was indicative of the Sōtō school's rivalry with the Rinzai School.[53][35]

The same tale is also included in the Hiragana-bon Inga monogatari, Book 4, Tale 17 as "Matter of receiving [heavenly] punishment for badly conducting the laws of Buddhism"[ac] where the priest's name is given as Kan'etsu (関悦).[53][54] Whereas the Katakana text described the body strewn "hither thither",[53] the hiragana redaction adds the hands and ankle were torn, and parts were hung over tree branches.[54]

Rōō sawa

Aizu domain samurai Misaka Haruyoshi (三坂春編)'s collection of strange tales, Rōō sawa (老媼茶話; "Old Women’s Chat over Tea", Kanpō 2/1742), contains two tales about evil women whose corpse is hunted by black clouds which appear to be the kasha, though the term kasha is not named explicitly. In Book three, "Lost soul",[ad] there was a certain ill-considerate[55] wife of a man named Nagashima Ichizaemon residing in Kamigawara-machi, Utsunomiya, Shimotsuke Province who murdered an adopted son out of the malice (as she was a barren woman), and was in turn killed by the spirit of the dead. During her funeral procession.[ae] a thunderstorm came and dark clouds came after her body. In Book five, "Dead woman of Kutsu village",[af] the wife of a peasant named Shōjirō of Iwaki, Mutsu Province (now Iwaki, Fukushima) was at once miserly and greedy, ill-considerate, and envious, murdering 20 people by curse, but herself dying at age 37. Though dead, she still moved about refusing to be shaved by the priest, and her face was like an ogre's. During the funerary procession, the thunderous rain came and she was engulfed in black clouds, so that other people all fled. By the next day her remains were gone.[56]

Shin Chomonjū

The Shin Chomonjū (新著聞集; pub. 1749) also contains references to kasha as fire cart, for which cf. hi no kuruma § Shin chomonjū. There are also mentions of the kasha as monster, cf. below:

Slicing off kasha's hand

Again in Part ten on Strange Events of this work, is an entry titled "Cutting off the hand of an ogre in a cloud at the place of funeral"[ag]. It tells of a (historical) samurai named Matsudaira Gozaemon participating in the funeral procession of his male cousin, when thunder began to rumble, and from a dark cloud that covered the sky, a kasha stuck out its bear-like foreleg, and attempted to steal the corpse. Matsudaira with his sword-stroke severed the creature's forepaw, which had three dreadful nails, covered by hair-like silver needles.[57][58][11]

A miserly hag taken by a kasha

This the tale was already anthologized in the earlier work Kokon inu chomonjū (古今犬著聞集; preface dated Tenna 4/1684),[56] but appears in the "Shin Chomonjū", Part fourteen on "Calamities" under the entry "A miserly and greedy hag taken by a kasha".[ah] The daimyo lord of Hizen Domain named Ōmura Inaba-no-kami and his retinue were passing through the bay area of Bizen Province when a black cloud appeared from afar, then a scream "Oh, woe [is me]"[ai] resounded, with human feet seen sticking out of that cloud. When the daimyo's vassals dragged it down, it turned out to be the corpse of an old woman. According to those in the neighborhood, the hag was terribly stingy, and was detested by all around her, but one time when she went outside to go to the bathroom, a black cloud suddenly swooped down and took her away. The narrator explains this must have been the handiwork of the devil which people call kasha in the world at large.[57][11]

Toriyama Sekien

Toriyama Sekien drew and wrote the text for Gazu Hyakki Yagyō (1786), and in the second or yō (Chinese: yang) volume, he provides a captioned illustration for kasha.[38][aj]

According to Sekien's text, the lore of the kasha stealing bodies from funeral grounds and graves was already widespread across Japan in his time. Some places prescribed placing a stone in the coffin or chanting to try to ward off the cat monster. Its true identity is an ancient cat, that is, a nekomata.[18][19]

Bōsō Manroku

According to Chihara Kyosai (茅原虚斎)'s Bōsō Manroku (茅窓漫録) (pub. Tenpō4/1833),the legend of the kasha could be seen in western parts of Japan including Izumo (Shimane Prefecture) and Satsuma (Kagoshima Prefecture), and in Eastern parts of Japan as well. It is said that when a sudden gust of wind and rain threatens a coffin to be blown away during a funeral, the protecting monk casting his juzu (Buddhist rosary) will cause nothing to go amiss, however, without this ritual, the body may be blown away and be lost. Though the author considers it a silly superstition, rumors will start that the victim must have done evil deeds during his lifetime, and the kasha from hell must have ushered the person away. The kasha would reputedly tear the body apart, and leave it hanging on a rock in the mountains or a tree.[61][41][62]

This author further mocks the ignorant masses for naming a body-snatching monster after a vehicle (hell's fire-cart), and seeks a better name for it as could be found in Chinese classics, finding mōryō (魍魎) (Chinese pronunciation: wǎngliǎng).[61][58] The accompanying illustration is captioned "魍魎", which is forcibly read as "kwasha/kasha" (cf. image right).[11][60][ak]

Shōkō-in relic

Hozumi Takahiko (穂積隆彦)'s Setagaya shiki (世田谷私記; pub. 1813) records that among the items kept at Shōkō-in temple in Setagaya-ku, Tokyo were the kasha's claws. A certain wise and virtuous abbot at this temple dispelled the kasha attempting to possess the dead, causing several claws to fall off. The writer claims to have viewed these 4 claws in Bunka 9/1812.[65][66]

Similar things

Things of the same kind as kasha, or things thought of as a different name for kasha, are as follows.[8]

In Akihata village, Kanra District, Gunma Prefecture (now part of Kanra town), a monster that would eat human corpses were called tenmaru, and in order to defend against this, the (round coffin) was capped by a bamboo basket before burial.[67]

In the Izumi region, Kagoshima Prefecture, beings called called kimotori (lit. "liver-taker[s]") are said to appear at the gravesite after funerals.[11]

Development over time

Kasha literally means "fire cart"[3] or "burning chariot",[4] or possibly just "wheels of fire".[2] Originally (during Japan's Middle Ages and early modern era) the kasha were fiery transport carts to convey the damned to Buddhist hell,[68] as depicted as such in Buddhist writings such as rokudo-e.[12][3] Kasha also appeared in Buddhist paintings of the era, notably jigoku-zōshi (Buddhist 'hellscapes', paintings depicting the horrors of hell), where they were depicted as flaming carts pulled by demons or oni.[69][70] The tale of the kasha was used by the Buddhist leadership to persuade the populace to avoid sin.[12]

Over time, the image of the kasha evolved from a chariot of fire to a sort of body-snatching monster. Earlier, in such literature as discussed above (under § In classics) of the early to mid- Edo Period,[al] the kasha as yōkai was depicted in ogre[4] or oni-like forms, either as a gokusotsu ("wardens of hell", ogre that torments the damned) or Gozu and Mezu ("Ox-Head and Horse-Head", also guardians of hell), then from the latter half of the 16th century[71] as thunder i.e. the ogre-like Raijin ("thunder god").[72] The conception of the kasha as a cat appeared around the late 17th century (cf. Kōsekishū dated 1693, above}).[73] Toriyama Sekien illustrated the kasha in cat-like style in his illustrated album of various yōkai, the Gazu hyakki yakō (1776),[72][4] and afterwards, it became increasingly commonplace to conceive of the kasha as a cat-type yōkai.[74]

There is some considerable discussion on the origin of the feline appearance of the modern kasha. One recent explanation is that the folklore about the cat nekomata stealing corpses got conflated with the fire-chariot conveying the damned to hell.[75][aj] Others such as manga artist Shigeru Mizuki believed that the kasha was given a feline appearance due to influence from the aforementioned corpse-robbing mōryō which the Chinese call wangliang.[22][8][am]

In Japan, from old times, cats were seen as possessing supernatural abilities, and there are legends such as "one must not let a cat get near a corpse" and "when a cat leaps over a coffin, the corpse inside the coffin will wake up". Also, in the collection of setsuwa (narratives) the Uji Shūi Monogatari from medieval Japan, a gokusotsu would drag a burning hi no kuruma ("fire cart"), it is said that they would attempt to take away the corpses of sinners, or living sinners. It has thus been determined that the legend of the kasha was born as a result of the mixture of legends concerning cats and the dead, and the legend of the "hi no kuruma" that would steal away sinners.[8]

Another popular viewpoint is that kasha were given the cat-like appearance after it was noted that in rare cases, cats will consume their deceased owners.[69] This is a rather unusual occurrence, but there are recorded modern cases of this.[76]

Another theory states that the legend of kappa making humans drown and eating their innards from their anuses was born as a result of the influence of this kasha. The kasha was sometimes associated with the mōryō yokai, which is an earlier form of the kappa, where it picked up the trait of consuming the organs of the dead.[77][63]

Transitive meanings

The term kasha ("fire car")[an] also refers to the yarite or yarite babā (遣り手婆)[ao] who disciplined the geisha or prostitutes at the yūkaku pleasure quarters.[11][78]

In the old Harima Province (now Hyōgo Prefecture), old women of unsavory character were called "kasha-baba" ("fire-cart hags"), with the subtext that they were like cat monsters.[13]

See also

Explanatory notes

- ^ whether cat-like or thunder-god-like

- ^ A pet of over 30 years in the Kōsekishū (1693),[9] a 100 year-old kusha in the lore of Himakajima island,[10]

- ^ Even though Hiroshi Aramata's Map forcibly localized the kasha at Niigata Prefecture (and Iwate).[20]

- ^ Examples of the aforementioned folktale type Neko danka ("cat patron") has been collected from all over the country by Keigo Seki (1978) Nihon mukashbanashi taisei 6 under the "grateful animal" category, and by folklorist Akira Fukuda,[21] though they may not clearly feature a kasha.

- ^ This term usually refers to concubines or servants entertaining (togi, i.e. performing sexual services) at night (yoru) for a lord or master.

- ^ Source found this observed in 5 places including Shiiba village and Kurosako in Miyazaki city.

- ^ In Haramachi in Miyazaki city; as well as in Ōtsukachō.

- ^ Tsuma (妻) in Saito city, Miyazaki.

- ^ ex-Nakagō village, Kitamorokata District (now Umekita in Miyakonojō city).

- ^ Tano town

- ^ Former Haruna town, Gunma District, former Ōmama, Yamada District.

- ^ Height of 869.2m

- ^ Also called by the longer form madō kusha on Himakajima island..[31]

- ^ Original text reads 筬 but emended to箴 for osa, meaning the "reed for weaving".

- ^ Japanese: バクには食わせん.

- ^ Japanese: 火車には食わせん.

- ^ Japanese definition of kinsei or "modern" is mutable and differs from western convention. Often it means Azuchi-Momoyama to Tokugawa period.

- ^ As well as the Gozu/Mezu (Ox-Head and Horse-Head),[38] which were also bailiffs of hell.

- ^ Japanese: 「猫火車と成て人の死骸を取事」.

- ^ Japanese: 「火車説ならびに猫取死骸事」.

- ^ Beside the printed edition, there are older manuscripts, so it was probably written sometime during the span from late medieval to the early Edo Period, and not necessarily later thant Kanwa kii.

- ^ Japanese: 「越後上田の庄にて、葬りの時、雲雷きたりて死人をとる事」, in the ge volume of he manuscript, part 1.

- ^ Styled 雲東庵 in this text, but properly 雲洞庵.

- ^ Hokkō Zenshuku was supposedly counseled the Echigo warlord Uesugi Kenshin about Sending salt to the enemy.[45] But the historical priest had been invited by Kenshin's arch-enemy Takeda Shingen to assume a post of head priest in Shinano Province in Eiroku10/1567, so he could hardly be involved in this event in Echigo at the later date.[35]

- ^ Said to be of woven hemp material, in kō-zome dye color (i.e.., dyed in kō color , 香染, "incense wood dyed", "clove-dyed", close to light French beige).

- ^ Japanese: 「生ながら、火車(かしや)にとられし女の事」.

- ^ Japanese: 「悪見ニ落タル僧自他ヲ損ズル事」.

- ^ 八屋 in the text, but now standardly written 蜂屋.

- ^ Japanese: 「仏法を、あしくすゝめて、罰あたりし事」.

- ^ Japanese: 「亡魂」.

- ^ Text gives nobe okuri (野辺送り; lit. "field-edge send-off").

- ^ Japanese: 「久津村の死女」.

- ^ Japanese: 「葬所に雲中の鬼の手を斬とる」.

- ^ Japanese: 「慳貪老婆火車つかみ去る」.

- ^ Japanese: あら悲しや.

- ^ a b In Sekien's Gazu Hyakki Yagyō, yo (陽; "yang" as in ying-yang) the entries on ubagabi ("hag fire") and kasha are given back to back, because the author saw connection between the two yōkai, according to scholarly opinion.[38] Kuramoto (2016) explains the connection as relating to the fact that the hag whose job was to bully prostitutes at the brothel into submission, the yarite was also colloquially called kasha or "fire cart"[38] (cf. § Transitive meanings, infra.) But note also that ubagabi is connected with the act of stealing oil (to light lamps or lanterns), while it is well-known in the kaidan (ghost stories) genre that the bakeneko cat monster licks this type of oil.

- ^ The essay Mimibukuro by Negishi Shizumori, Book four "Kiboku no koto" (鬼僕の事), also has a segment entitled "The one called mōryō" (魍魎といへる者なり).[63][8]

- ^ Set in, or perhaps already created in the Azuchi-Momoyama period, but prominently copied or printed in the early to mid- Edo Period,

- ^ In the aforementioned "Bōsō Manroku", the characters 魍魎 were read "kuwashya" i.e. kasha.

- ^ Otherwise written as kasha (花車; "flower car") or kasha (香り車; "fragrant car")[38].

- ^ The term "yarite" in turn originally denoted skilled drivers of oxcarts.[11]

References

- ^ Rikan Mitsukata; Nabeta Gyokuei [in Japanese] (1881). "Kasha" くわしゃ. Kaibutsu gahon 怪物画本. Wada Mojūrō. fol. 20r. ndljp:12984890.

- ^ a b Joly, Henri L. (1910). "Bakemono". Transactions and Proceedings of Japan Society, London (in Japanese). 9. Japan Society of London: 28.

- ^ a b c d Yen, Chih-hung (2001). "Representations of the Bhaisajyaguru Sutra at Tun-huang". Kaikodo Journal. 20: 168. ZDB-ID 2602228-X.

- ^ a b c d e Marks, Andreas (2023). Japanese Yokai and Other Supernatural Beings: Authentic Paintings and Prints of 100 Ghosts, Demons, Monsters and Magicians. Tuttle Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 9781462923830.

- ^ Harold B. Lee Library (2025). "Bakemono no e scroll" 化物之繪. Brigham Young University. Retrieved 2025-05-22.

- ^ Katsuda (2012), pp. 1, 19.

- ^ a b c Katsuda (2012), pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Murakami, Kenji [in Japanese] (2000), Yōkai jiten 妖怪事典 (in Japanese), Mainichi Shimbunsha, p. 103–104, ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0

- ^ a b c Mozume (1916), p. 112.

- ^ a b Segawa, Kiyoko [in Japanese] (1951). Himakajima minzokushi 日間賀島民俗誌 [Folk customs of the people of Himaga-shima]. Tōkō Shoin. p. 81. apud Katsuda (2012), p. 8

- ^ a b c d e f g Kyōgoku, Natsuhiko; Tada, Katsumi [in Japanese] (2000). Yōkai zukan 妖怪図巻. Kokusho kankokai. pp. 150–151. ISBN 978-4-336-04187-6.

- ^ a b c d e Tsunemitsu, Tōru [in Japanese]; Yamada, Shōji [in Japanese]; Iikura, Yoshiyuki, eds. (July 2013). Nihon kaii yōkai daijiten 日本怪異妖怪大事典. Tōkyō: Tokyodo shuppan. ISBN 9784490108378. OCLC 852779765.

- ^ a b c Harimagaku Kenkyūsho, ed. (2005). 播磨の民俗探訪. 神戸新聞総合出版センター. pp. 157–158. ISBN 978-4-3430-0341-6.

- ^ Katsuda (2012), p. 7 and p. 30 (Eng. summary).

- ^ Yanagita, Kunio (December 1935). "Mukashibanashi oboegaki" 昔話覺書. Mukashibanashi kenkyū 昔話研究. 1 (8): 4. ndljp:1494980.

- ^ Katsuda (2012), pp. 7, 19–20 and p. 30 (Eng. summary)

- ^ Katsuda (2012), pp. 8–9 and p. 23 "various places (各地)",

- ^ a b Toriyama, Sekien (2021), "Kasha" 火車 , Edo yōkaiga taizen 江戸妖怪画大全(鳥山石燕 全妖怪画集・解説付き特別編集版) (in Japanese), Edo Rekishi Library

- ^ a b Toriyama, Sekien (2016). "Kasha". Japandemonium Illustrated: The Yokai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien. Translated by Hiroko Yoda; Matt Alt. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. p. 35. ISBN 9780486800356. OCLC 909082541.

- ^ a b c Aramata, Hiroshi; Ōya, Yasunori (2021). "Kasha" 火車. Aramata Hiroshi no Nihon zenkoku yōkai mappu アラマタヒロシの日本全国妖怪マップ (in Japanese). Shuwa System. p. 50. ISBN 9784798065076.

- ^ a b Katsuda (2012), p. 20.

- ^ a b Shigeru, Mizuki (2014). Ketteihan Nihon Yōkai Taizen: Yōkai - Anoyo - Kami-sama 決定版 日本妖怪大全 妖怪・あの世・神様 [Japanese Yōkai Encyclopedia Final Edition: Yōkai, Other Worlds and Gods]. Tokyo: Kodansha-Bunko. ISBN 978-4-06-277602-8.

- ^ a b c Taanaka, Kumao (April 1979). "Miyagi-ken no sōsō・bosei" 宮崎県の葬送・墓制. Kyūshū no sōsō・bosei 九州の葬送・墓制. Meigen Shobo. pp. 258–259. ndljp:12168576; Reprinted in: Taanaka, Kumao (November 1981). MIyazaki-ken shomin seikatsushi 宮崎県庶民生活誌. Hyūga minzoku gakkai jimukyoku. p. 280?. ndljp:9774061; Excerpted in: Miyazaki Prefecture (1992), p. 280?

- ^ a b Gunma-ken shi shiryō-hen 群馬県史資料編, vol. 26, Grunma Prefecture, 1982, p. 1235 apud Katsuda (2012), p. 8

- ^ Sasaki, Shigeru (10 July 1913). "Tōno zakki" 遠野雑記. Kyōdo kenkyū 郷土研究. 1 (7): 51, via International Research Center for Japanese Studies database 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース

- ^ Kikuchi, Sansai [in Japanese], ed. (1923). "Etta no dōka ni tsuite" 第九章 ヱツタの同化に就て. Eta-zoku ni kansuru kenkyū 穢多族に関する研究 [Study of the "eta", or social outcasts, with emphasis on their origins and history]. Sanseisha Shoten. p. 222. ndljp:978676.

- ^ Yanagita, Kunio (1955). Sōgō minzoku goi shū 綜合日本民俗語彙. Vol. 1. Heibonsha. p. 468, after Minka denshō 9 (6) & (7).

- ^ Yamaguchi, Bintarō [in Japanese] (2003). Tōhoku yōkai zukan とうほく妖怪図鑑. Mumyosha. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-4-89544-344-9.

- ^ Tsuchihashi, Riki [in Japanese] (1973-12-20), "Shōjin no minwa" 精進の民話, Kaiji 甲斐路 (Cumul. 24), Yamanashi kyōdo kenkyūkai: 41–42, retrieved 2008-09-01 – via International Research Center for Japanese Studies database 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース (Informant: Minejirō Kobayashi 小林峯次郎).

- ^ Kōnō, Masafumi (1984-03-31). "Dai-8-shō Dai-3-setsu 3. Shi to ifuku" 第八章 第三節:三 死と衣服. Ehime-ken shi Minzoku 愛媛県史 民俗. Vol. 下巻. 愛媛県. p. 390. Retrieved 2008-09-01 – via International Research Center for Japanese Studies database 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース.

- ^ Murakami (2000), p. 312.

- ^ "Miyazaki-ken Higashiusuki-gun Saigō-son" 宮崎県東臼杵郡西郷村, Minkan Saihō 民俗採訪 (Cumulative Shōwa 38 Issue): 6, 1965-07-01, retrieved 2008-09-01 – via International Research Center for Japanese Studies database 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース

- ^ 桂又三郎. "中国民俗研究 1巻3号 阿哲郡熊谷村の伝説". 怪異・妖怪伝承データベース. Retrieved 2008-09-01.

- ^ Katsuda (2012), p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Katsuda (2012), p. 18.

- ^ a b Katsuda (2012), p. 27.

- ^ Kuramoto (2016), p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e Kuramoto (2016), p. 26.

- ^ Tsutsumi (1999), pp. 110–111 apud Katsuda (2012), p. 20

- ^ Tsujidō Chōfūshi (1704), "Kan4-no-3: Kasha setsu narabini neko ga shigai wo toru koto" 巻四之三:火車説幷猫取死骸事, Tama sudare 多満寸太礼(たますだれ) apud Kuramoto (2016), p. 26.

- ^ a b c Tsutsumi (1995), pp. 311–312.

- ^ "Kii zōdanshū" 奇異雑談集. Edo kaidanshū 江戸怪談集. Vol. 1. Iwanami Shoten. 1989. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-4-00-302571-0.

- ^ Katsuda (2012), pp. 18–19.

- ^ Suzuki Bokushi [in Japanese]; Iwase Kyōsui (1836). "Hokkō zenji yūki no zu" 北高禅師勇気図. Hokuetsu seppu: shohen 3-kan 2-hen4-kan 北越雪譜 初編3巻2編4巻. 2-hen 3-kan:fol. 12v–13a. Retrieved 2025-08-10. via Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin (Stabi) Digitalisierte Sammlungen

- ^ a b c Tsutsumi (1995), p. 313.

- ^ Mozume (1916), pp. 114–115.

- ^ Suzuki Bokushi [in Japanese] (1997). "Hokkō oshō" 北高和尚. Hokuetsu seppu 北越雪譜. Translated by Ikeuchi, Osamu [in Japanese]. Shogakukan. pp. 201–202. ISBN 978-4-09-251035-7.

- ^ Hokuetsu Seppu 12-hen, 3-kan[46][47] plain text@Aozora bunka.

- ^ Suzuki Bokushi [in Japanese] (1986). Snow country tales. Life in the other Japan 北越雪譜. Translated by Hunter, Jeffrey; Lesser, Rose. New York: Weatherhill. pp. 316–317. ISBN 0-8348-0210-4.

- ^ a b Suzuki Shōsan (1989). "Hiragana-bon Inga monogatari" 平仮名本 因果物語. In Takada, Mamoru [in Japanese] (ed.). Edo kaidanshū 江戸怪談集. Vol. 2. Iwanami Shoten. pp. 180–182.

- ^ a b Tsukano (2008), pp. 6–7.

- ^ Yokoyama, SUmio [in Japanese] (1979). Owari to Mino no kirishitan 尾張と美濃のキリシタン. Chunichi Shuppansha. pp. 102–103.

- ^ a b c Mibu shoin henshū-bu, ed. (1929). "Inga monogatari ni.." 因果物語に... Mikan Kikōsho sōkan dai-1-shū dai-1 Tengu-mei kō 未刊・稀覯書叢刊 第1輯 第1 天狗名義考. Mibu shoin henshū-bu. pp. 201–202. ndljp:1446571/1/19.

- ^ a b Tsukano (2008), pp. 5–6.

- ^ Text gives jaken which comes from the Buddhist concept of wrong viewedness.

- ^ a b Katsuda (2012), p. 26.

- ^ a b Kamiya Yōyūken (1974). "Shin chomonjū" 新著聞集. In Nihon zuihitsu taisei henshū-bu (ed.). Nihon zuihitsu taisei 日本随筆大成. Vol. 〈第2期〉5. Yoshikawa Kobunkan. p. 239. ISBN 978-4-642-08550-2.

- ^ a b Katsuda (2012), p. 25.

- ^ Imaizumi, Jōsuke [in Japanese]; 畠山健, eds. (1890–1892), "Bōsō Manroku: Kasha" 茅窓漫録:火車, Hyakka zeirin: 10-kan 百家説林 : 10巻, vol. 1, Yoshikawa Hanshichi, pp. 1086–1087

- ^ a b Chihara Kyosai (1994) [1833]. "Bōsō manroku" 茅窓漫録. Nihon zuihitsushū 日本随筆大成. Vol. 〈1st Period〉22. Yoshikawa Kobunkan. pp. 352–353. ISBN 978-4-642-09022-3.

- ^ a b Chihara Kyosai (1833). Bōsō Manroku "kasha"..[59][60]

- ^ Inoguchi (1977), pp. 46–47.

- ^ a b Negishi, Shizumori [in Japanese] (1991). Hasegawa, Tsuyoshi [in Japanese] (ed.). Mimibukuro 耳嚢. Vol. 中. Iwanami Shoten. p. 125. ISBN 978-4-00-302612-0.

- ^ Tsutsumi (1999), p. 104.

- ^ Hozumi Takahiko ed. (1813) Setagaya shiki 世田谷私記 1.1[9][64]

- ^ Inoguchi (1977), p. 48.

- ^ Murakami (2000), p. 236.

- ^ Katsuda (2012), pp. 1, 30.

- ^ a b Davisson, Zack (2017). Kaibyō : the supernatural cats of Japan (First ed.). Seattle, WA: Chin Music Press. ISBN 9781634059169. OCLC 1006517249.

- ^ "Tokyo Exhibit Promises A Hell of An Experience". Japan Forward. 2017-08-05. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ Katsuda (2012), p. 30.

- ^ a b Kuramoto (2016), pp. 26, 27.

- ^ Kuramoto (2016), pp. 19, 30.

- ^ Katsuda (2012), p. 9.

- ^ Tsutsumi (1999) Kisei setsuwa to zensō, "Chapter 2.I. Kasha to zen sō 火車と禅僧 [the kasha and the Zen priest], apud Kuramoto (2016), p. 26 and note 13).

- ^ Sperhake, J.P (2001). "Postmortem Bite Injuries Cause by a Domestic Cat". Archiv für Kriminologie. 208 (3–4): 114–119. PMID 11721602.

- ^ Kyōgoku & Tada (2000), p. 147.

- ^ De Becker, Joseph Ernest (1905) [1899]. The Nightless City: Or, The History of the Yoshiwara Yūkwaku 不夜城 (5 ed.). Yokohama: Max Nössler. p. 60.

Bibliography

- Inoguchi, Shōji [in Japanese] (1977). Nihon no sōshiki 日本の葬式. Tsukuma Shobo. ISBN 9784480012401.

- Katsuda, Itaru (March 2012). "Kasha no tanjō" 火車の誕生 [Birth of kasha] (PDF). Kokuritsu Rekishi Minzoku Hakubutsukan kenkyū hōkoku 国立歴史民俗博物館研究報告 (174): 7–30.

- Kuramoto, Akira (31 January 2016). "Toriyama Sekien Gazu hyakki yakō yō no kan wo yomu" 鳥山石燕『画図百鬼夜行』陽の巻を読む [Birth of kasha] (PDF). Nihon bungaku kenkyū 日本文学研究. 51. Baiko Gakuin University: 22–32.

- Tsutsumi, Kunihiko [in Japanese] (1995-11-01). Kinsei bukkyō setsuwa no kenkyū: shōdō to bungei 近世仏教説話の研究 : 唱導と文芸 (Ph.D.). Keio University. doi:10.11501/3109113.

- Tsutsumi, Kunihiko [in Japanese] (1999). Kinsei setsuwa to zensō 近世説話と禅僧. Izumi Shoin. ISBN 9784870889613.

- Miyazaki Prefecture (March 1992), Miyazaki-ken shi 宮崎県史, vol. 2, Miyazaki Prefecture, ndljp:12168576

- Mozume, Takami [in Japanese], ed. (1922) [1916], "Kasha" 火車(くわしゃ), Kōbunko, vol. 7, Kōbunko kankōkai, pp. 747–750

- Mozume, Takami [in Japanese], ed. (1922) [1916], "Hi no kuruma" 火車 ひのくるま, Kōbunko, vol. 16, Kōbunko kankōkai, pp. 1069–1071

- Tsukano, Akiko (2008-09-30). "Kinsei shoki kaii shōsetsu no kyōzai-ka no teian: Kasha-tan wo chūshin ni" 近世初期怪異小説の教材化の提案 -火車譚を中心に- [The Proposal of Making the Mysterious Stories in the Early Stages of the Modern Times Teaching Materials -Focusing on Kasya Tales-] (PDF). Waseda daigaku daigaku-in kyōikugaku kenkyū-ka kiyō Bessatsu 早稲田大学大学院教育学研究科紀要 別冊 [The Bulletin of the Graduate School of Education of Waseda University Separate]. 16 (1): 1–12. hdl:2065/30163.

External links

- Short infos about Kashas Archived 2012-08-01 at the Wayback Machine (English)