1937 Indian provincial elections

| |||||||||||||||||||||

1585 provincial seats contested | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

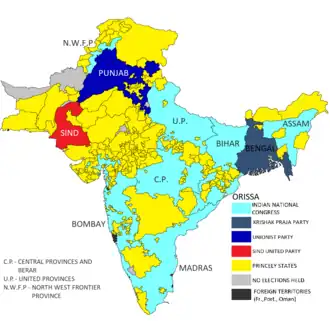

Provincial elections were held in British India in the winter of 1936–37 as mandated by the Government of India Act 1935. Elections were held in eleven provinces - Madras, Central Provinces, Bihar, Orissa, the United Provinces, the Bombay Presidency, Assam, the North-West Frontier Province, Bengal, Punjab and Sind.

The final results of the elections were declared in February 1937. The Indian National Congress emerged in power in five of the provinces, Bombay, Madras, the Central Provinces, the United Provinces, the North-West Frontier Province, Bihar, and Orissa. The exceptions were Bengal, where the Congress was nevertheless the largest party, Punjab, Sindh, and Assam. The All-India Muslim League failed to form the government in any province.

The Congress ministries resigned in October and November 1939, in protest against Viceroy Lord Linlithgow's action of declaring India to be a belligerent in the Second World War without consulting the elected representatives of the Indian population.

Electorate

The Government of India Act 1935 increased the number of enfranchised people.[1][2] Approximately 30 million people, among them some women, gained voting rights. This number constituted one-sixth of Indian adults. The Act provided for a limited adult franchise based on property qualifications such as land ownership and rent, and therefore favored landholders and richer farmers in rural areas.[2] Previously only Muslims were entitled to reserved seats & separate electorates, dating back to the Government of India Act 1919. However, under the Communal Award, this benefit was also extended to include women, Sikhs, Christians, Anglo-Indians & Backward Tribes. An attempt to create a separate electorate for Dalits distinct from that of Hindus was thwarted by the Poona Pact.

Legislative Assemblies[3]

| Province | Total | Hindu | Muslim | Others | Women | Christian | Anglo-Indian | European | Commerce | Landholders | Labour | Universities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assam | 108 | 47 (inclusive of 7 reserved for Dalits) | 34 | 9 (Backward Tribes) | 1 (Hindu) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| Bengal | 250 | 78 (66 rural & 12 urban, inclusive of 30 reserved for Dalits) | 117 (111 rural & 6 urban) | 0 | 4 (2 Hindu & 2 Muslim) | 2 | 4 | 11 | 19 | 5 | 8 | 2 (Calcutta University & Dhaka University) |

| Bihar | 152 | 93 (88 rural & 5 urban, inclusive of 15 reserved for Dalits) | 39 (34 rural & 5 urban) | 0 | 4 (3 Hindu & 1 Muslim) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 (Patna University) |

| Bombay | 175 | 115 (101 rural & 14 urban, inclusive of 15 reserved for Dalits) | 29 (23 rural & 6 urban) | 0 | 6 (4 Hindu urban, 1 Muslim urban & 1 Hindu rural) | 3 (2 rural & 1 urban) | 2 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 1 (Bombay University) |

| Central Provinces | 113 | 84 (74 urban, 10 rural, inclusive of 20 reserved for Dalits) | 14 (12 rural & 2 urban) | 1 (Backward Tribes) | 3 (Hindu) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 (Nagpur University) |

| Madras | 215 | 146 (131 rural & 15 urban, inclusive of 30 reserved for Dalits) | 28 (26 rural & 2 urban) | 1 (Backward Tribes) | 8 (3 Hindu urban, 3 Hindu rural, 1 Muslim urban & 1 Christian urban) | 8 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 1 (Madras University) |

| North West Frontier Province | 50 | 9 (6 rural & 3 urban) | 36 (33 rural & 3 urban) | 3 (Sikhs) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Orissa | 60 | 45 (inclusive of 6 reserved for Dalits) | 4 | 4 (nominated members) | 2 (Hindu) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Punjab | 175 | 42 (34 rural & 8 urban, inclusive of 8 reserved for Dalits) | 84 (75 rural & 9 urban) | 31 (29 Sikh rural & 2 Sikh urban) | 4 (2 Muslim, 1 Hindu & 1 Sikh) | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 (University of the Punjab) |

| Sind | 60 | 18 (15 rural & 3 urban) | 33 (31 rural & 2 urban) | 0 | 2 (1 Hindu urban & 1 Muslim urban) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| United Provinces | 228 | 140 (123 rural & 17 urban, inclusive of 20 reserved for Dalits) | 64 (51 rural & 13 urban) | 0 | 6 (3 Hindu rural, 1 Hindu urban, 1 Muslim rural & 1 Muslim urban) | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 1 (Lucknow University) |

| Total | 1586 | 817 (inclusive of 151 reserved for Dalits) | 468 | 49 (34 Sikh, 11 Backward Tribes & 4 nominated) | 40 (28 Hindu, 10 Muslim, 1 Christian & 1 Sikh) | 20 | 12 | 27 | 56 | 37 | 38 | 8 |

Legislative Councils[3]

| Province | Hindu | Muslim | European | Others | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assam | 10 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 18 |

| Bengal | 10 (8 rural & 2 urban) | 17 (16 rural & 1 urban) | 3 | 27 (elected by MLAs) | 57 |

| Bihar | 9 | 4 | 1 | 14 (elected by MLAs) | 28 |

| Bombay | 20 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 26 |

| Madras | 35 | 7 | 1 | 3 (Christian) | 46 |

| United Provinces | 34 (29 rural & 5 urban) | 17 (12 rural & 5 urban) | 1 | 0 | 52 |

| Total | 118 | 56 | 9 | 44 | 227 |

Schedule

| Province | Polling begins | Polling ended |

|---|---|---|

| Assam | 18th January | 8th February |

| Bengal | 18th January | 26th January |

| Bihar | 22nd January | 28th January |

| Bombay | 11th February | 18th February |

| Central Provinces | 4th February | 19th February |

| Madras | 15th February | 20 February |

| North West Frontier Province | 1st February | 1st February |

| Orissa | 20th January | 27th January |

| Punjab | 18th January | 3rd August |

| Sind | 1st February | 1st February |

| United Provinces | 7th February | 18th February |

Election campaign

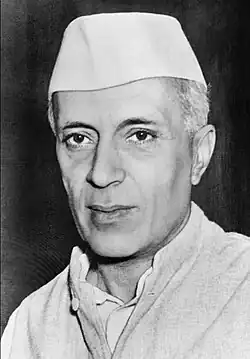

At its 1936 session held in the city of Lucknow, the Congress party, despite opposition from the newly elected Nehru as the party president, agreed to contest the provincial elections to be held in 1937.[4] The released Congress leaders anticipated the restoration of elections. They now had a stronger standing with their reputation enhanced by the civil disobedience movement under Gandhi's leadership.[5] Through the elections the Congress sought to convert its popular movement into a political organisation.

The party's election platform had downplayed communalism and Nehru continued this attitude with the initiation of the March 1937 Muslim mass contact program. But the elections demonstrated that of the 468 Muslim seats the Congress had contested just 58 of them and won only 25 of those. In spite of this poor showing the Congress persisted in its claim that the party was representative of all communities.[1] The Congress ministries did not succeed in attracting their Muslim countrymen. This was largely unintentional.[6]

Results

The Congress won 706 out of around 1586 seats in a resounding victory, and went on to form seven provincial governments. The Congress formed governments in United provinces, Bihar, the Central Provinces, Bombay and Madras.[6]

The 1937 elections demonstrated that neither the Muslim League nor the Congress represented Muslims. It also demonstrated the provincial moorings of Muslim politics.[7] The Muslim League captured around 25 percent of the seats reserved for Muslims. The Congress Muslims achieved 6 percent of them. Most of the Muslim seats were won by regional Muslim parties.[8] None of Congress' Muslim candidates won in Sindh, Punjab, Bengal, Orissa, United Provinces, Central Provinces, Bombay and Assam.[7] Most of the 25 Muslim seats the Congress captured were in NWFP, Madras and Bihar.[9]

Legislative assembly results[3]

| Province | Congress | Muslim League | Other parties | Independents | Muslim seats | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assam | 33 | 10 | 5 (Assam Valley Muslim Party)

5 (Surma Valley Muslim Party) 3 (United People's Party) |

21 (Hindus)

10 (Muslims) 9 (Backward Tribes) 8 (Commerce & Tea plantations) 1 (European) 1 (Christian) 1 (Woman) |

34 | 108 |

| Bengal | 54 | 40 | 36 (Krishak Praja Party) | 42 (Muslims)

37 (Hindus) 14 (Commerce) 11 (Europeans) 4 (Anglo-Indians) 2 (Christians) |

120 | 250 |

| Bihar | 92 | 0 | 16 (Independent Party)

6 (United Party) 3 (Majlis-e-Ahrar) 3 (Depressed Classes League) |

15 (Hindus)

11 (Muslims) 2 (Commerce) 2 (Europeans) 1 (Anglo-Indian) 1 (Christian) |

40 | 152 |

| Bombay | 85 | 18 | 13 (Independent Labour Party)

10 (Non-Brahman) 3 (Democratic Swarajya Party) 2 (Khoti Sabha) 1 (Congress Nationalist Party) |

18 (Hindus)

13 (Muslims) 4 (Commerce) 3 (Europeans) 2 (Anglo-Indians) 3 (Christians) |

30 | 175 |

| Central Provinces | 70 | 5 | 8 (Muslim Parliamentary Board)

3 (Independent Labour Party) 3 (Non-Brahman) 2 (Congress Nationalist Party) 1 (Hindu Mahasabha) |

13 (Hindus)

1 (Muslim) 2 (Europeans) 1 (Anglo-Indian) |

14 | 113 |

| Madras | 159 | 9 | 21 (Justice Party)

1 (People's Party) 1 (Muslim Progressive Party) |

7 (Hindus)

7 (Muslims) 4 (Commerce) 3 (Europeans) 2 (Anglo-Indians) 1 (Christian) |

29 | 215 |

| North West Frontier Province | 19 | 0 | 21 (Muslim Independent Party)

7 (Hindu-Sikh Nationalist Party) |

2 (Muslims)

1 (Hindu) |

36 | 50 |

| Orissa | 36 | 0 | 6 (United Party) | 6 (Hindus)

4 (Nominated) 3 (Muslims) 1 (Christian) |

4 | 60 |

| Punjab | 18 | 2 | 94 (Unionist Party)

14 (Khalsa National Party) 11 (Hindu Election Board) 10 (Shiromani Akali Dal) 2 (Majlis-e-Ahrar) 2 (Majlis-e-Ittehad-e-Millat) 1 (Congress Nationalist Party) 1 (Socialist Party) |

11 (Hindus)

5 (Muslims) 3 (Sikhs) 1 (Labour) |

86 | 175 |

| Sind | 7 | 0 | 17 (Sind United Party)

16 (Sindh Muslim League) 12 (Hindu Mahasabha) 1 (Sind Azad Party) |

3 (Hindus)

2 (Europeans) 1 (Muslim) 1 (Commerce) |

34 | 60 |

| United Provinces | 133 | 27 | 22 (National Agriculturist Party)

1 (Liberal Party) |

30 (Muslims)

10 (Hindus) 2 (Europeans) 2 (Christians) 1 (Anglo-Indian) |

65 | 228 |

| Total | 706 (including 25 seats reserved for Muslims) | 111 | 398

(including 236 Muslim representatives from parties other than the Congress & the Muslim League) |

367 (including 125 Muslims) | 468 | 1586 |

Legislative councils results[3]

| Province | Congress | Muslim League | Other parties | Independents | Europeans | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assam | 0 | 0 | 6 (Assam Valley Muslim Party) | 10 (Hindus) | 2 | 18 |

| Bengal | 9 | 14 | 8 (Krishak Praja Party) | 12 (Hindus)

5 (Muslims) |

6 | 57 |

| Bihar | 8 | 0 | 3 (United Party)

3 (Independent Party) |

11 (Hindus)

2 (Muslims) |

1 | 28 |

| Bombay | 13 | 2 | 2 (Democratic Swarajya Party)

1 (Liberal Party) |

4 (Hindus)

3 (Muslims) |

1 | 26 |

| Madras | 26 | 3 | 5 (Justice Party)

1 (People's Party) |

6 (Hindus)

2 (Muslims) 2 (Christians) |

1 | 46 |

| United Provinces | 8 | 0 | 4 (National Agriculturists)

1 (Liberal Party) |

22 (Hindus)

16 (Muslims) |

1 | 52 |

| Total | 64 | 19 | 37 (including 22 Muslims) | 95 (including 28 Muslims) | 12 | 227 |

Government formation

The Congress initially refused to form governments in the provinces it had won beacuse the Government of India Act empowered the Governor to over-rule Cabinet decisions & wield control over finances. However, S. Satyamurti launched a campaign within the Congress party, convincing Mahatma Gandhi to direct Congress leaders in accepting premiership positions. On 22th June, Governor-General Lord Linlithgow issued a statement declaring the willingness of the British administration to work alongside the Congress within the ambit of the GoI Act. On 1st July, the Congress Working Committee formally took the decision to form governments in the provinces.[10][11]

Madras Presidency

In Madras, the Congress formed the government by winning 159 seats, eclipsing the incumbent Justice Party (21 seats).[12] The Muslim League won 9 out of the 28 seats reserved for the Muslims. On the initial refusal of Congress to assume power, Kurma Venkata Reddy Naidu of the Justice Party was sworn in as Chief Minister of Madras State on 1st April by the governor John Erskine. 3 months later, the Congress staked claim & C. Rajagopalachari was sworn in. The legislatures convened under the chairmanship of B. Sambamurthy (assembly) & Dr. U. Rama Rao (council).

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| C. Rajagopalachari | Chief Minister, Home and Finance |

| T. Prakasham | Revenue |

| Dr. T. S. S. Rajan | Public Health |

| Dr. P. Subbarayan | Education and Law |

| Yakub Hasan | Public works |

| V. I. Munuswamy Pillai | Agriculture and Rural Development |

| S. Ramanathan | Public Information |

| V. V. Giri | Industries and Labour |

| K. Raman Menon | Courts and Prisons |

| H. Gopala Reddy | Local administration |

Sind

The Sind Legislative Assembly had 60 members. The Sind United Party emerged the leader with 21 seats, and the Congress secured 5 seats.[14] Mohammad Ali Jinnah had tried to set up a League Parliamentary Board in Sindh in 1936, but he failed, though 72% of the population was Muslim.[15] Though 34 seats were reserved for Muslims, the Muslim League could secure none of them.[16] Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah of the Sindh Muslim League was sworn in as the Chief Minister of Sind with Hindu Mahasabha support on 28th April by Governor Sir Lancelot Graham. Within a year, he was replaced by Allah Bux Soomro of the Sind United Party. The assembly convened under the chairmanship of Bhojsingh Pahlajani.

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah | Chief Minister, Home and Finance |

| Mukhi Gobindram Pritamdas | Irrigation |

| Mir Bandeh Ali Khan Talpur | Revenue |

United Provinces

The UP legislature consisted of a Legislative Council of 52 elected and 6 or 8 nominated members and a Legislative Assembly of 228 elected members: some from exclusive Muslim constituencies, some from "General" constituencies, and some "Special" constituencies.[17] The Congress won a clear majority in the United Provinces, with 133 seats,[18] while the Muslim League won only 27 out of the 64 seats reserved for Muslims.[19]

The Congress refused to form coalition with the League, even though two parties had a verbal understanding to do so.[6] The party offered the Muslim League a role in government if it merged itself into the Congress Party. While this position had a good basis it proved to be a mistake.[1] The Congress disregarded that even though they had captured the large part of UP's general seats, they had not won any of the reserved Muslim seats, of which the Muslim League had won 29.[20]

On the Congress' refusal to assume power, the Nawab of Chhatari from the National Agriculturist Party was sworn in on 3rd April by the governor Harry Graham Haig. 3 months later, the Congress laid claim to government formation and Govind Ballabh Pant was sworn in as the Chief Minister of United Provinces. The legislatures convened under the chairmanship of Purushottamdas Tandon (assembly) & Sir Sitaram (council).

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| Govind Ballabh Pant | Chief Minister, Finance, Forest and Police |

| Rafi Ahmed Kidwai | Revenue, Agriculture, Publicity and Jails |

| Dr. Kailashnath Katju | Justice, Industries and Co-operatives |

| Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit | Local self-goverment |

| Pyarelal Sharma | Education |

| Hafiz Muhammad Ibrahim | Communication |

Assam

In Assam, the Congress won 33 seats out of a total of 108 making it the single largest party,[21] though it was not in a position to form a ministry. Sir Muhammed Saadulah of the Assam Valley Muslim Party was sworn in as the Chief Minister of Assam on 1st April by the governor Robert Niel Raid. [22] One year later he was replaced with Gopinath Bordoloi of the Congress. The legislatures convened under the chairmanship of Basanta Kumar Das (assembly) & Monomohan Lahiri (council).

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| Muhammed Saadulah | Chief Minister |

| Rohini Kumar Chaudhuri | |

| Abu Nasr Waheed | |

| Ali Haider Khan | |

| Rev. J. J. M. Nichols Roy |

Bombay Presidency

In Bombay, the Congress won 86 out of the 175 seats, falling just short of gaining half the seats. However, it was able to draw on the support of some small pro-Congress groups to form a working majority. After the Congress initially refuse to take power, the governor Michael Knatchbull sworn in Dhanjishah Cooper of the Non-Brahmin party as the Chief Minister of Bombay on 1 April. 4 months later, the Congress staked claim for government formation and B.G. Kher was sworn in. The legislatures convened under chairmanship of Ganesh Vasudev Mavalankar (assembly) & Mangaladas Mancharam Pakvasa (council).

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher | Chief Minister, Education |

| Anna Babaji Latthe | Finance |

| Kanaiyalal Maneklal Munshi | Home and Legal Affairs |

| Manchershah Dhanjibhai Gilder | Health and Excise |

| Morarji Desai | Revenue, Agriculture and Rural Development |

| M. Y. Nuri | Public Works |

| L. M. Patel | Local self-goverment and miscellaneous |

Punjab

Sikandar Hayat Khan of the Unionist Party, with support of the Khalsa National Party and Hindu Election Board was sworn in as the Chief Minister of Punjab on 5th April by the governor Sir Herbert Emerson.[23] The assembly convened under the chairmanship of Shahabuddin Virk.

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| Sikandar Hayat Khan | Chief Minister, Law & Order |

| Manohar Lal | Finance |

| Sundar Singh Majithia | Revenue |

| Chhotu Ram | Development |

| Khizar Hayat Tiwana | Public Works |

| Abdul Haye | Education |

Bengal

A. K. Fazlul Huq of the Krishak Praja Party formed a coalition government with the support of Khawaja Nazimuddin of the Muslim League.[24] He was sworn in on 1st April as the Chief Minister of Bengal by the governor Sir John Anderson. The legislatures convened under the chairmanship of Azizul Huq (assembly) & Satyendra Chandra Mitra (council).

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| A. K. Fazlul Huq | Chief Minister, Education |

| Nalini Ranjan Sarkar | Finance |

| Khawaja Nazimuddin | Home |

| Bijoy Prasad Singh Ray | Revenue |

| Khawaja Habibullah | Agriculture and Industry |

| Sris Chandra Nandy | Communication and Public Works |

| Hussain Shaheed Suhrawardy | Commerce and Labour |

| Musharraf Hossain | Judicial and Legislature |

| Syed Nausher Ali | Local self-goverment |

| Prasanna Deb Raikut | Forest and Excise |

| Mukunda Behari Mullick | Co-operative Credit & Rural indebtedness |

North West Frontier Province

In the overwhelmingly Muslim majority North-West Frontier Province, Congress won 19 out of 50 seats and was able, with minor party support, to form a ministry.[12] Due to the Congress' initial refusal to form government, the governor Sir George Cunningham sworn in Sahibzada Abdul Qayyum of the Muslim Independent Party as the Chief Minister on 1st April. 5 months later, the Congress laid claims to government formation & Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan, (brother of Bacha Khan) was sworn in. The assembly convened under the chairmanship of Malik Khuda Baksh Khan.

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| Khan Abdul Jabbar Khan | Chief Minister |

| Qazi Ataullah Khan | |

| Khan Mohammad Abbas Khan | |

| Bhanjuram Gandhi |

Other provinces

As the Congress initially refused to assume power, other people had to be sworn in. On 1st April, governor Sir Maurice Garnier Hallett sworn in Muhammad Yunus of the Muslim Independent Party as the Chief Minister of Bihar. On that day, the Maharaja of Paralakhamudi Krushna Chandra Gajapati (representing landholders) was sworn in as Chief Minister of Odisha by governor John Hubback. In Central Provinces, an interim government was formed by Dr. E. Raghavendra Rao, sworn in by the governor Sir Hyde Gowan.

In July, the Congress laid stake to government formation, thus Shri Krishna Sinha in Bihar & Bishwanath Das in Orissa were sworn in. In August Narayan Bhaskar Khare was sworn in as Chief Minister of Central Provinces. Within a year, he was sacked from the Congress & replaced by Ravishankar Shukla. The legislatures in Bihar were convened under the chairmanship of Sachchidananda Sinha (assembly) & Ramdayalu Singh (council). Legislative assemblies in Orissa & Central Provinces were chaired by Mukunda Prasad Das & Ghanshyam Singh Gupta respectively.

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| Shri Krishna Sinha | Chief Minister, Education and Local self-goverment |

| Anugrah Narayan Sinha | Land Revenue, Finance and Development |

| Dr. Syed Mahmud | Law and Order |

| Jaglal Choudhury | Agriculture, Labour and Unemployment |

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| Bishwanath Das | Chief Minister, Home, Finance and Education |

| Nityananda Kanungo | Revenue, Health, Public Works and Local self-goverment |

| Bodhram Dubey | Law and Commerce |

| Name | Department |

|---|---|

| Narayan Bhaskar Khare | Chief Minister, Home |

| P. B. Gole | Revenue |

| D. K. Mehta | Finance |

| Ravishankar Shukla | Education |

| N. Y. Shareef | Law and Justice |

| Ramrao Deshmukh | Public Works |

| Dwarka Prasad Mishra | Local self-goverment |

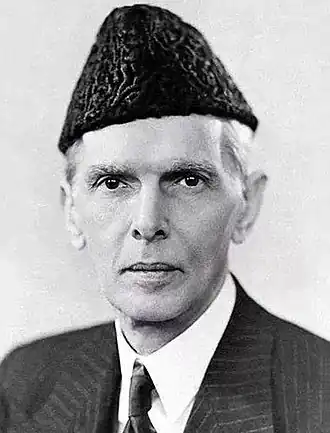

Muslim League

Jinnah took a nationalist stance and emulated the Congress's electoral campaign and appointed Muslim League Parliamentary Boards for the 1937 elections. Through this he expected to advance the party as a coalition partner for the Congress which they might need to form provincial governments. He miscalculated that the separate electorates system, with a larger electorate, would produce good results for the Muslim League.[25] Of the 482 seats reserved for Muslims the League won just 109. The League won 29 seats in the United Provinces where it had competed for 35 out of the 66 seats for Muslims.[7] The League's top performance was in provinces where Muslims were minorities; there it cast itself as a protector of the community.[1] Its performance in Punjab, where it won just two of the seven seats it vied for, was unsuccessful. It performed a little better in Bengal, capturing 39 of the 117 seats for Muslims, but could not form a government.[7]

Muslim preference was to be represented by regional parties which were allied with those non-Muslims who were not supportive of the Congress.[26] The Congress was victorious throughout India in the open constituencies. Muslim league was confronted with the fact that Hindu majority provinces would be ruled by Hindus but Muslim league would not rule the largest provinces with Muslim majorities: Bengal and Punjab. The Congress domination over the government made the prospects of federal Muslim politicians appear dismal.[26] Regional parties kept the League out of power in those provinces with Muslim majorities while in the Hindu majority provinces it was unwanted by the Congress.[25] Antagonised by this rebuff the League stepped up its efforts to attract a popular following.[27]

Resignation of Congress ministries

On 3 September 1939, Viceroy of India Lord Linlithgow declared India to be at war with Germany alongside Britain.[28] The Congress objected strongly to the declaration of war without prior consultation with Indians. The Congress Working Committee suggested that it would cooperate if a central Indian national government were formed and a commitment were made to India's independence after the war.[29] The Muslim League promised its support to the British,[30] with Jinnah calling on Muslims to help the Empire by "honourable co-operation" at the "critical and difficult juncture", while asking the Viceroy for increased protection for Muslims.[31]

The government did not come up with any satisfactory response. Viceroy Linlithgow could only offer to form a 'consultative committee' for advisory functions. Thus, Linlithgow refused the demands of the Congress. On 22 October 1939, all Congress ministries were called upon to tender their resignations. Both Viceroy Linlithgow and Muhammad Ali Jinnah were pleased with the resignations.[32][29] On 2 December 1939, Jinnah put out an appeal, calling for Indian Muslims to celebrate 22 December 1939 as a "Day of Deliverance" from Congress:[33]

I wish the Musalmans all over India to observe Friday 22 December as the "Day of Deliverance" and thanksgiving as a mark of relief that the Congress regime has at last ceased to function. I hope that the provincial, district and primary Muslim Leagues all over India will hold public meetings and pass the resolution with such modification as they may be advised, and after Jumma prayers offer prayers by way of thanksgiving for being delivered from the unjust Congress regime.

References

- ^ a b c d Ian Talbot; Gurharpal Singh (2009). The Partition of India. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-521-85661-4.

- ^ a b David Anthony Low (1991). Eclipse of empire. Cambridge University Press. p. 154. ISBN 0-521-45754-8.

- ^ a b c d e Denis Taylor, David (1971). "Indian Politics and the Elections of 1937". SOAS University of London – via SOAS Research Online.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ B. R. Tomlinson (1976). The Indian National Congress and the Raj, 1929–1942: The Penultimate Phase. The Macmillan Press. pp. 57–60. ISBN 978-1-349-02873-3.

- ^ Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9.

- ^ a b c Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9.

- ^ a b c d Peter Hardy (1972). The Muslims of British India. Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-521-09783-3.

- ^ Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004) [First published 1986]. A History of India (PDF) (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2015.

- ^ Peter Hardy (1972). The Muslims of British India. Cambridge University Press. pp. 224–225. ISBN 978-0-521-09783-3.

- ^ Satyamurti, S. (2008). The Satyamurti Letters: The Indian Freedom Struggle Through the Eyes of a Parliamentarian. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-1488-1.

- ^ Menon, Visalakshi (9 October 2003). From Movement To Government: The Congress in the United Provinces, 1937-42. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-7619-9620-0.

- ^ a b Joseph E. Schwartzberg (1992). A Historical Atlas of South Asia (2nd impression, with additional material ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 222. ISBN 0-19-506869-6. Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k H.N. Mitra (1937). Indian Annual Register, 1937. January - June. Vol. I. Annual Register Office.

- ^ Jones, Allen Keith (2002). Politics in Sindh, 1907-1940: Muslim identity and the demand for Pakistan. Oxford University Press. pp. 73, 81. ISBN 978-0-19-579593-6.

- ^ Ayesha Jalal (1994) [First published 1985]. The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- ^ Shila Sen (1976). Muslim Politics in Bengal, 1937-1947. Impex India. p. 89. OCLC 2799332.

- ^ P. D. Reeves (1971). "Changing Patterns of Political Alignment in the General Elections to the United Provinces Legislative Assembly, 1937 and 1946". Modern Asian Studies. 5 (2): 111–142. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00002973. JSTOR 312028. S2CID 145663295.

- ^ Visalakshi Menon (2003). From movement to government: the Congress in the United Provinces, 1937-42. Sage Publications. p. 60.

- ^ Abida Shakoor (2003). Congress-Muslim League tussle 1937-40: a critical analysis. Aakar Books. p. 90.

- ^ Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9.

- ^ Chiriyankandath, James (March 1992). "'Democracy' under the Raj: Elections and separate representation in British India". The Journal of Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 30 (1): 57. doi:10.1080/14662049208447624.

- ^ "Ministry-making in Assam". The Indian Express. 13 March 1937. p. 12.

- ^ Arora, Subhash Chander (1990). Turmoil in Punjab politics. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 17. ISBN 978-81-7099-251-6.

- ^ Ayesha Jalal (1994) [First published 1985]. The Sole Spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League and the Demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- ^ a b Hermann Kulke; Dietmar Rothermund (2004) [First published 1986]. A History of India (PDF) (4th ed.). Routledge. p. 314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 February 2015.

- ^ a b Peter Hardy (1972). The Muslims of British India. Cambridge University Press. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-521-09783-3.

- ^ Barbara Metcalf; Thomas Metcalf (2006). A Concise History of Modern India (PDF) (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-521-86362-9.

- ^ Ayesha Jalal (1994) [First published 1985]. The sole spokesman: Jinnah, the Muslim League, and the demand for Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-521-45850-4.

- ^ a b Sekhar Bandyopadhyay (2004). From Plassey to Partition: A History of Modern India. India: Orient Longman. p. 412. ISBN 978-81-250-2596-2.

- ^ Victoria Schofield (2003). Afghan Frontier: Feuding and Fighting in Central Asia. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-1-86064-895-3. Retrieved 10 December 2007.

- ^ Stanley Wolpert (22 March 1998). "Lecture by Prof. Stanley Wolpert: Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah's Legacy to Pakistan". Jinnah of Pakistan. Humsafar.info. Archived from the original on 27 December 2007. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ^ Anderson, Ken. "Gandhi - The Great Soul". The British Empire: Fall of the Empire. Archived from the original on 16 October 2012. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

- ^ Nazaria-e-Pakistan Foundation. "Appeal for the observance of Deliverance Day, issued from Bombay, on 2nd December, 1939". Quaid-i-Azam's Speeches & Messages to Muslim Students. Archived from the original on 29 July 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2007.