History of Australia (1945–1983)

| The Commonwealth of Australia — Post-war reconstruction and transformation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1945–1983 | |||

| |||

Albert Namatjira painting in Alice Springs, c.1957 | |||

| Location | Australia | ||

| Monarch(s) | George VI Elizabeth II | ||

| Key events | Post-war immigration; Snowy Mountains Scheme; end of White Australia policy; involvement in Korean War and Vietnam War; 1967 referendum on Indigenous rights; 1975 Australian constitutional crisis; Papua New Guinea independence; rise of Multiculturalism; Australian New Wave cinema | ||

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Australia |

|---|

|

|

The history of Australia from 1945 to 1983 encompasses the transformation of Australia from a war-torn nation into a modern, multicultural society during the post-war reconstruction years. This period began with the aftermath of World War II under Prime Minister Ben Chifley's Labor government, which initiated massive immigration programs, industrial expansion, and the foundations of Australia's welfare state. The years witnessed profound social and political changes, including the gradual dismantling of the White Australia policy, the historic 1967 referendum granting constitutional recognition to Indigenous Australians, and the emergence of multiculturalism as official policy.

Australia's foreign policy during these decades was characterised by strong ties to both the United Kingdom and the United States, with active participation in Cold War conflicts including the Korean War and the Vietnam War. However, the period also marked Australia's gradual assertion of independence in international affairs, culminating in significant diplomatic shifts by the early 1980s. Domestically, the years saw alternating Labor and Liberal/Country Party governments navigate economic challenges, social reform, and changing cultural attitudes. The period concluded in 1983 with the election of Bob Hawke's Labor government, marking the beginning of a new years of economic reform and modernisation.

End of the 1940s

In 1944, the Liberal Party of Australia was formed, with Robert Menzies as its founding leader. The party would come to dominate the early decades of the post-war period. Outlining his vision for a new political movement in 1944, Menzies said:

"…[W]hat we must look for, and it is a matter of desperate importance to our society, is a true revival of liberal thought which will work for social justice and security, for national power and national progress, and for the full development of the individual citizen, though not through the dull and deadening process of socialism.[1]

In April 1945, Prime Minister John Curtin despatched an Australian delegation which included attorney-general and minister for external affairs H. V. Evatt to discuss formation of the United Nations. Australia played a significant mediatory role in these early years of the United Nations, successfully lobbying for an increased role for smaller and middle-ranking nations and a stronger commitment to employment rights into the U.N. Charter. Evatt was elected president of the third session of the United Nations General Assembly (September 1948 to May 1949).[2]

When Labor Prime Minister John Curtin passed away in July 1945. Frank Forde served as prime minister from 6–13 July, before the party elected Ben Chifley as Curtin's successor.[3] Chifley, a former railway engine driver, won the 1946 election. His government introduced national projects, including the Snowy Mountains Scheme and an assisted immigration program and pursued centralist economic policies – making the Commonwealth the collector of income tax, and seeking to nationalise the private banks. At the conference of the New South Wales Labor Party in June 1949, Chifely sought to define the labour movement as having:[4]

[A] great objective – the light on the hill – which we aim to reach by working for the betterment of mankind... [Labor would] bring something better to the people, better standards of living, greater happiness to the mass of the people’.

With an increasingly uncertain economic outlook, after his attempt to nationalise the banks and the coal strike by the Communist-dominated Miners Federation, Chifley lost office at the 1949 federal election to Menzies' newly established Liberal Party, in coalition with the Country Party.[5]

Immigration and the post-war boom

After World War II, Australia launched a massive immigration program, believing that having narrowly avoided a Japanese invasion, Australia must "populate or perish." As Prime Minister Ben Chifley would later declare, "a powerful enemy looked hungrily toward Australia. In tomorrow's gun flash that threat could come again. We must populate Australia as rapidly as we can before someone else decides to populate it for us."[6] Hundreds of thousands of displaced Europeans, including for the first time large numbers of Jews, migrated to Australia. More than two million people immigrated to Australia from Europe during the 20 years after the end of the war.

From the outset, it was intended that the bulk of these immigrants should be mainly from the British Isles, and that the post-war immigration scheme would preserve the British character of Australian society. Although Great Britain remained the predominant source of immigrants, the pool of source countries was expanded to include Continental European countries in order to meet Australia's ambitious immigration targets. From the late 1940s onwards, Australia received significant waves of people from countries such as Greece, Italy, Malta, Germany, Yugoslavia and the Netherlands. Australia actively sought these immigrants, with the government assisting many of them and they found work due to an expanding economy and major infrastructure projects.[7]

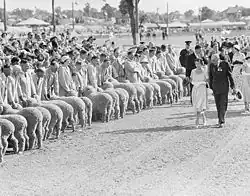

The Australian economy stood in sharp contrast to war-ravaged Europe, and newly arrived migrants found employment in a booming manufacturing industry and government assisted programs such as the Snowy Mountains Scheme. This hydroelectricity and irrigation complex in south-east Australia consisted of sixteen major dams and seven power stations constructed between 1949 and 1974. It remains the largest engineering project undertaken in Australia. Necessitating the employment of 100,000 people from over 30 countries, to many it denotes the birth of multicultural Australia.[7]

In 1949 the 1941–1949 Labor government (led by Ben Chifley after John Curtin's death in 1945) was defeated by a Liberal–National Party Coalition government headed by Menzies. Politically, the Menzies government and the Liberal Party of Australia dominated much of the immediate post-war years, defeating the Chifley government in 1949, in part over a Labor proposal to nationalise banks[8] and following a crippling coal strike influenced by the Australian Communist Party. Menzies became the country's longest-serving Prime Minister and the Liberal party, in coalition with the rural based Country Party, won every federal election until 1972.

As in the United States in the early 1950s, allegations of communist influence in society saw tensions emerge in politics. Refugees from Soviet dominated Eastern Europe immigrated to Australia, while to Australia's north, Mao Zedong won the Chinese Civil War in 1949 and in June 1950, Communist North Korea invaded South Korea. The Menzies government responded to a United States led United Nations Security Council request for military aid for South Korea and diverted forces from occupied Japan to begin Australia's involvement in the Korean War. After fighting to a bitter standstill, the UN and North Korea signed a ceasefire agreement in July 1953. Australian forces had participated in such major battles as Kapyong and Maryang San. Seventeen thousand Australians had served and casualties amounted to more than 1,500, of whom 339 were killed.[9]

During the course of the Korean War, the Menzies government attempted to ban the Communist Party of Australia, first by legislation in 1950 and later by referendum, in 1951.[10] While both attempts were unsuccessful, further international events such as the defection of minor Soviet Embassy official Vladimir Petrov, added to a sense of impending threat that politically favoured Menzies’ Liberal-CP government, as the Labor Party pushed centralist economics and split over concerns about the influence of the Communist Party over the Trade Union movement, resulting in a bitter split in 1955 and the emergence of the breakaway Democratic Labor Party (DLP). The DLP remained an influential political force, often holding the balance of power in the Senate, until 1974; its preferences supported the Liberal and Country Party.[11] The Labor party was led by H. V. Evatt after Chifley's death in 1951. Evatt retired in 1960, and Arthur Calwell succeeded him as leader, with a young Gough Whitlam as his deputy.[12]

Menzies presided over a period of sustained economic boom and the beginnings of sweeping social change – with the arrivals of rock and roll music and television in the 1950s. In 1956, television in Australia began broadcasting, Melbourne hosted the Olympics and, for the first time, performing artist Barry Humphries performed the character of Edna Everage as a parody of a house-proud housewife of staid 1950s Melbourne suburbia (the character only later morphed into a critique of self-obsessed celebrity culture). It was the first of many of his satirical stage and screen creations based around quirky Australian characters.

In 1958, Australian country music singer Slim Dusty, who would become the musical embodiment of rural Australia, had Australia's first international music chart hit with his bush ballad "A Pub with No Beer",[13] while rock and roller Johnny O'Keefe's Wild One became the first local recording to reach the national charts,[14] peaking at #20.[15][16] Before sleeping through the 1960s Australian cinema produced little of its own content in the 1950s, but British and Hollywood studios produced a string of successful epics from Australian literature, featuring home grown stars Chips Rafferty and Peter Finch.

Menzies remained a staunch supporter of links to the monarchy and British Commonwealth and formalised an alliance with the United States, but also launched post-war trade with Japan, beginning a growth of Australian exports of coal, iron ore and mineral resources that would steadily climb until Japan became Australia's largest trading partner.[17]

In the early 1950s, the Menzies government saw Australia as part of a "triple alliance", in concert with both the US and traditional ally Britain.[18] At first, "the Australian leadership opted for a consistently pro-British line in diplomacy", while at the same time looking for opportunities to involve the US in South East Asia.[19] Thus, other than the Korean War, the government also committed military forces to the Malayan Emergency and hosted British nuclear tests after 1952.[20] Australia was also the only Commonwealth country to offer support to the British during the Suez Crisis.[21]

Menzies oversaw an effusive welcome to Queen Elizabeth II on the first visit to Australia by a reigning monarch, in 1954. However, as British influence declined in South East Asia, the US alliance came to have greater significance for Australian leaders and the Australian economy. British investment in Australia remained significant until the late 1970s, but trade with Britain declined through the 1950s and 1960s. In the late 1950s the Australian Army began to re-equip using US military equipment. In 1962, the US established a naval communications station at North West Cape, the first of several built over the next decade.[22][23] Most significantly, in 1962, Australian Army advisors were sent to help train South Vietnamese forces, in a developing conflict the British had no part in.

The ANZUS security treaty, which had been signed in 1951, had its origins in Australia's and New Zealand's fears of a rearmed Japan, but found new impetus through anti-communism. Its obligations on the US, Australia and New Zealand are vague, but its influence on Australian foreign policy thinking, at times significant.[24] The SEATO treaty, signed only three years later, clearly demonstrated Australia's position as a US ally in the emerging cold war. On 26 November 1967, Australia became the seventh nation to put a satellite into Earth orbit, launching WRESAT from Woomera.

When Menzies retired in January 1966, he was replaced as Liberal leader and prime minister by Harold Holt. The Holt government increased Australian commitment to the growing War in Vietnam; oversaw conversion to decimal currency and faced Britain's withdrawal from Asia by visiting and hosting many Asian leaders and by expanding ties to the United States, hosting the first visit to Australia by an American president, his friend Lyndon B. Johnson. Significantly, Holt's government introduced the Migration Act 1966, which effectively dismantled the vestigial mechanisms of the White Australia policy and increased access to non-European migrants, including refugees fleeing the Vietnam War. Holt also called the 1967 Referendum which removed the discriminatory clause in the Constitution of Australia which excluded Aboriginal Australians from being counted in the census – the referendum was one of the few to be overwhelmingly endorsed by the Australian electorate (over 90% voted 'yes').[25]

Holt won the 1967 election with the largest parliamentary majority in 65 years, but Holt drowned while swimming at a surf beach in December 1967 and was replaced by John Gorton (1968–1971). The Gorton government began winding down Australia's commitment to Vietnam, increased funding for the arts, standardised rates of pay between the men and women and continued moving Australian trade closer to Asia. The Liberals suffered a decline in voter support at the 1969 election and internal party division saw Gorton replaced by William McMahon (1971–1972) and, facing a reinvigorated Australian Labor Party led by Gough Whitlam, the Liberals entered their final stretch in office of a record 23 straight years period.[26]

1960s and 1970s: The "Australian New Wave"

.jpg)

From the mid-1960s, evidence of a new and more independent sense of national pride and identity began to emerge in Australia. In the early 1960s, the National Trust of Australia began to be active in preserving Australia's natural, cultural and historic heritage. Australian TV, while always dependent on US and British imports, saw locally made dramas and comedies appear, and programs such as Homicide developed strong local loyalty while Skippy the Bush Kangaroo became a global phenomenon. Liberal Prime Minister John Gorton, a battle scarred former fighter pilot, described himself as "Australian to the bootheels" and the Gorton government established the Australian Council for the Arts, the Australian Film Development Corporation and the National Film and Television Training School.[26]

The late 1960s and early 1970s are often associated with a flowering of Australian culture. Indigenous Australians achieved greater rights, immigration restrictions and censorship laws were swept aside, theatre and opera companies were established across the country, and Australian rock music blossomed. The 1971 South Africa rugby union tour of Australia was influential in raising awareness of Aboriginal injustice in Australia and also led Australia to become the first Western nation to cut sporting ties with South Africa. In a significant move against South Africa's apartheid regime, many Australians (including Wallabies) demonstrated against tours by the racially selected South African team.[27] The Australian media tycoon Kerry Packer altered the traditionalist ethos of the game of cricket in the 1970s, inventing World Series Cricket from which have evolved many aspects of the various modern international forms of the game.

The iconic Sydney Opera House finally opened in 1973 after numerous delays. In the same year, Patrick White became the first Australian to win a Nobel Prize for Literature.[28] Australian History had begun to appear on school curriculums by the 1970s[29] and from the early 1970s, the Australian cinema began to produce the Australian New Wave of feature films based on uniquely Australian themes. Film funding began under the Gorton government, but it was the South Australian Film Corporation that took the lead in supporting filmmaking and among their great successes were quintessential Australian films Sunday Too Far Away (1974) Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975), Breaker Morant (1980) and Gallipoli (1981). The national funding body, the Australian Film Commission, was established in 1975.

Significant changes also occurred to Australia's censorship laws after the new Liberal Minister for Customs and Excise, Don Chipp, was appointed in 1969. In 1968, Barry Humphries and Nicholas Garland's cartoon book featuring the larrikin character Barry McKenzie was banned. Yet only a few years later, the book had been made as a film, partly with the support of government funding.[30] Anne Pender suggests that the Barry Mckenzie character both celebrated and parodied Australian nationalism. Historian Richard White also argues that "while many of the plays, novels and films produced in the 1970s were intensely critical of aspects of Australian life, they were absorbed by the ‘new nationalism’ and applauded for their Australianness."[31]

Australia and the Vietnam War

.jpg)

The Menzies government despatched the first small contingent of Australian military training personnel to aid South Vietnam in 1962, so beginning Australia's decade long involvement in the Vietnam War. Ngo Dinh Diem, the leader of the government in South Vietnam, had requested security assistance from the US and its allies. The Australian government supported the commitment as part of global effort to stem the spread of communism in Europe and Asia.

Initially popular, Australia's participation in Vietnam, and particularly the use of conscription, later became politically contentious and saw massive protests, though they were for the most part peaceful. The United States launched a major escalation of the war in 1965 and the Holt government which succeeded Menzies, increased Australia's military commitment to the conflict. Holt won a massive majority in the 1967 Election.[25] By 1969 however, anti-war protests were gathering momentum and opposition to conscription was growing, with more people believing the war could not be won. The Gorton government (returned with a reduced majority at the 1969 Election) ceased to replace Australian personnel from 1970.[32] There were large Moratorium marches in 1970 and 1971 and Australia's troop commitment continued to wind down through 1971 with the last battalion leaving Nui Dat in November. The election of the Whitlam government in 1972 brought Australia's small remaining involvement in the war to an official close in June 1973 with the withdrawal of the last platoon guarding the Australian Embassy in Saigon. Australian forces were largely based at Nui Dat, Phước Tuy province, and participated in such notable battles as the Battle of Long Tan against the Viet Cong in 1966 and defending against the 1968 Tet Offensive. Almost 60,000 Australians had served in Vietnam and 521 had died as a result of the war. As the war became unpopular, protestors and conscienscious objectors became prominent and soldiers often met a hostile reception on their return home in the later stages of the conflict.[33]

In early 1975 the communists launched a major offensive resulting in the fall of Saigon on 30 April. The Royal Australian Air Force assisted in final humanitarian evacuations.[33] In the aftermath of the communist victory, Australia assisted in re-settlement of Vietnamese refugees, with thousands making their way to Australia through the 1970s and 1980s.[34]

Papua New Guinea and Nauru independence

Australia had administered Papua New Guinea and Nauru for much of the 20th century. British New Guinea (Papua) had passed to Australia in 1906. German New Guinea was captured by Australia during the First World War, becoming a League of Nations mandate after the war. Following the bitter New Guinea campaign of World War II which saw occupation of half the island by the Empire of Japan, the Territory of Papua and New Guinea was established by an administrative union between the Australian-administered Territory of Papua and Territory of New Guinea in 1949. Under Liberal Minister for External Territories Andrew Peacock, Papua and New Guinea adopted self-government in 1972 and on 15 September 1975, during the term of the Whitlam government in Australia, the Territory became the independent nation of Papua New Guinea.[35][36]

Australia had captured the island of Nauru from the German Empire in 1914. After Japanese occupation during World War II, it became a UN Trust Territory under Australia and remained so until achieving independence in 1968. In 1989 Nauru sued Australia in the International Court of Justice in The Hague for damages caused by mining. Australia settled the case out of court agreeing to a lump sum settlement of A$107 million and an annual stipend of the equivalent of A$2.5 million toward environmental rehabilitation.[37]

Whitlam, Fraser and the dismissal

Elected in December 1972 after 23 years in opposition, Labor won office under Gough Whitlam and introduced a significant program of social change and reform. Whitlam said before the election: "our program has three great aims. They are – to promote equality; to involve the people of Australia in … decision making…; and to liberate the talents and uplift the horizons of the Australian people."[38]

Whitlam's actions were immediate and dramatic. Within a few weeks the last milichlentary advisors in Vietnam were recalled, and national service ended. The People's Republic of China was recognised (Whitlam had visited China while Opposition Leader in 1971) and the embassy in Taiwan closed.[39][40] Over the next few years, university fees were abolished and a national health care scheme established. Significant changes were made to school funding, something Whitlam regarded as "the most enduring single achievement" of his government.[41] Divorce and family law was liberalised.

Whitlam's radical and imperious style eventually alienated many voters, and some of the state governments were openly hostile to his government. As it did not control the senate, much of its legislation was rejected or amended. The Queensland Country Party government of Joh Bjelke-Petersen had particularly bad relations with the Federal government. Even after it was re-elected at elections in May 1974, the Senate remained an obstacle to its political agenda. At the only joint sitting of parliament, in August 1974, six keys pieces of legislation wering passed.

In 1974, Whitlam selected John Kerr, a former member of the Labor Party and presiding Chief Justice of New South Wales to serve as Governor-General. The Whitlam government was re-elected with a decreased majority in the lower house in the 1974 Election. In 1974–75 the government thought about borrowing US$4 billion in foreign loans. Minister Rex Connor conducted secret discussions with a loan broker from Pakistan, and the Treasurer, Jim Cairns, misled parliament over the issue.[42] Arguing the government was incompetent following the Loans affair, the opposition Liberal-Country Party Coalition delayed passage of the government's money bills in the Senate, until the government would promise a new election. Whitlam refused, Malcolm Fraser, leader of the Opposition insisted. The deadlock came to an end when the Whitlam government was dismissed by the Governor-General, John Kerr on 11 November 1975 and Fraser was installed as caretaker prime minister, pending an election. The "reserve powers" granted to the Governor General by the Constitution of Australia, had allowed an elected government to be dismissed without warning by a representative of the Monarch.[43]

At elections held in late 1975, Malcolm Fraser and the Coalition were elected in a landslide victory.

The Fraser government won two subsequent elections. Fraser maintained some of the social reforms of the Whitlam years, while seeking increased fiscal restraint. His government included the first Aboriginal federal parliamentarian, Neville Bonner, and in 1976, Parliament passed the Aboriginal Land Rights Act 1976, which, while limited to the Northern Territory, affirmed "inalienable" freehold title to some traditional lands. Fraser established the multicultural broadcaster SBS, welcomed Vietnamese boat people refugees, opposed minority white rule in Apartheid South Africa and Rhodesia and opposed Soviet expansionism. A significant program of economic reform however was not pursued and, by 1983, the Australian economy was in recession, amidst the effects of a severe drought. Fraser had promoted "states’ rights" and his government refused to use Commonwealth powers to stop the construction of the Franklin Dam in Tasmania in 1982.[44] A Liberal minister, Don Chipp had split off from the party to form a new social liberal party, the Australian Democrats in 1977 and the Franklin Dam proposal contributed to the emergence of an influential Environmental movement in Australia, with branches including the Australian Greens, a political party which later emerged from Tasmania to pursue environmentalism as well as left-wing social and economic policies.[45]

Indigenous Australia

The struggle for Indigenous rights in Australia developed significantly throughout the 20th century, marked by key legislative changes, cultural recognition, and growing political representation. Campaigns for indigenous rights in Australia have a long history. In the modern years, 1938 was an important year. With the participation of leading indigenous activists like Douglas Nicholls, the Australian Aborigines Advancement League organised a protest "Day of Mourning" to mark the 150th anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet of British in Australia and launched its campaign for full citizenship rights for all Aborigines. In the 1940s, the conditions of life for Aborigines could be very poor. A permit system restricted movement and work opportunities for many Aboriginal people.

During the 1950s and 60s, the government pursued a policy of "assimilation" which sought to achieve full citizenship rights for Aborigines but also wanted them to adopt the mode of life of other Australians (which very often was assumed to require suppression of cultural identity).[46] " From the 1950s onwards, Australians began to rethink their attitudes towards racial issues, mirroring developments in other western nations. Momentum grew within the Aboriginal rights movement, building on the legacy of earlier generations of activism, and the historical White Australia Policy fell out of public favour. With uneven voting rights for Aboriginals based on states laws, the newly elected Menzies Government legislated in 1949 to ensure that all Indigenous Australians who'd served in the military received the right to vote. The Menzies Government's historic 1962 Commonwealth Electorate Act then removed the power of states to deny Aboriginals a vote in Federal Elections, and Queensland and Western Australia removed their prohibitions on state voting rights soon after. Menzies' successor Harold Holt called the landmark 1967 referendum, which received more than 90% approval from the electorate, and ended the discriminatory practice of not automatically counting Indigenous Australians in the electoral roll census, and of allowing the states, rather than the Federal Parliament, to legislate specifically for Indigenous Australians.[47] Contrary to frequently repeated mythology, this referendum did not cover citizenship on Aboriginal people, nor did it give them the vote: they already had both. However, transferring this power away from the State parliaments did bring an end to the system of Aboriginal reserve which existed in each state, which allowed Indigenous people to move more freely, and exercise many of their citizenship rights for the first time. From the late 1960s a movement for Indigenous land rights also developed. After the death of Holt, his successor John Gorton established the role of Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, and outlined a program for "advancement" of Aboriginal people by means of "the assimilation of Aboriginal Australians as fully effective members of a single Australian society":[48]

"In other words, without destroying Aboriginal culture, we want to help our Aboriginals to become an integral part of the rest of the Australian people, and we want the Aboriginals themselves to have a voice in the pace at which this process occurs."

— Prime Minister John Gorton, 12 July 1968

_dancing.jpg)

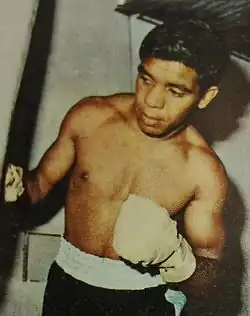

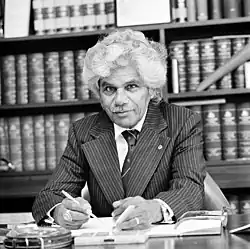

Gorton considered that the "primary aim" of government policy should be to "make Aboriginals self supporting", and to end dependence on welfare and charity.[49] The Government introduced the Aboriginal Study Grants Scheme (ABSTUDY) in 1969, in response to low participation of Indigenous Australians in higher education, and the Aboriginal Secondary Grants Scheme (ABSEG) in 1970 to boost participation in secondary schooling.[50] Menzies had established the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies in 1964 to help study and preserve traditional Aboriginal language, art and culture.[51] The period also saw a flowering of recognition for Aboriginal artists, sportspeople and performers, including the breakthrough fame of the landscape painter Albert Namatjira in the 1950s, singer Jimmy Little and world champion boxer Lionel Rose in the 1960s, and tennis player Evonne Goolagong Cawley and acting great David Gulpilil from the 1970s. Various groups and individuals were also active on the political front in the pursuit of equality and social justice from the 1960s. In the mid-1960s, one of the earliest Aboriginal graduates from the University of Sydney, Charles Perkins, helped organise freedom rides into parts of Australia to expose discrimination and inequality. In 1966, the Gurindji people of Wave Hill station (owned by the Vestey Group) commenced strike action led by Vincent Lingiari in a quest for equal pay and recognition of land rights.[52] Indigenous Australians began to take up representation in Australian parliaments during the 1970s. In 1971 Neville Bonner of the Liberal Party was appointed by the Queensland Parliament to replace a retiring senator, becoming the first Federal parliamentarian to identify as Aboriginal. Bonner was returned as a Senator at the 1972 election and remained until 1983. Hyacinth Tungutalum of the Country Liberal Party in the Northern Territory and Eric Deeral of the National Party of Queensland, became the first Indigenous people elected to territory and state legislatures in 1974. In 1976, Sir Douglas Nicholls was appointed Governor of South Australia, becoming the first Aborigine to hold vice-regal office in Australia.

Republicanism

Australia remained a constitutional monarchy under the Constitution of Australia adopted in 1901, with the duties of the monarch performed by a Governor-General selected by the Australian Government. Australian republicanism which had been a feature of the 1890s faded away during the First World War.[53] Support for the Monarchy of Australia peaked during the Menzies years with the wildly successful 1954 tour by Queen Elizabeth II. Prince Charles attended school in Australia during the 1960s. The issue of a republic did not arise again until the 1970s.

Military engagements in the late 20th century

Following the Vietnam War, Australian military forces were largely kept at home through the rest of the 1970s and 1980s, other than service in United Nations peacekeeping missions. RAAF helicopters operated in the Sinai; and Australian forces assisted in a British Commonwealth operation when Zimbabwe won its independence; as well as a similar operation in Namibia.[54]

See also

References

- ^ "Our History – Liberal Party of Australia". Liberal.org.au. 16 October 1944. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ G. C. Bolton. "Evatt, Herbert Vere (Bert) (1894–1965)". Biography – Herbert Vere (Bert) Evatt – Australian Dictionary of Biography. Adbonline.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Francis Forde – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "In office – Ben Chifley – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Ben Chifley – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. 13 June 1951. Archived from the original on 16 February 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "AUSTRALIA'S NEED OF POPULATION". The Morning Bulletin. Rockhampton, Qld. 6 December 1948. p. 1. Retrieved 23 April 2011 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b "The Snowy Mountains Scheme". Cultureandrecreation.gov.au. 20 March 2008. Archived from the original on 30 August 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Jan Bassett (1986) p.18

- ^ "Korean War 1950–53 | Australian War Memorial". Awm.gov.au. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ See Menzies in Frank Crowley (1973) Modern Australia in Documents, 1939–1970. p.222-226. Wren Publishing, Melbourne. ISBN 978-0-85885-032-3

- ^ Jan Bassett (1986) p.75-6

- ^ "Before office – Gough Whitlam – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 22 May 2019. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Laing, Dave (20 September 2003). "Slim Dusty". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "O'Keefe, John Michael (Johnny) (1935–1978)". O'Keefe, John Michael (Johnny). National Centre of Biography, Australian National University. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Kent, David (2005). Australian Chart Book 1940–1970. Turramurra, N.S.W.: Australian Chart Book, 2005. ISBN 978-0-646-44439-0.

- ^ "Long Way to the Top". ABC. Archived from the original on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2008.

- ^ + updated + (30 April 2010). "ABC The Drum – Conviction? Clever Kevin is no Pig Iron Bob". Abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 3 May 2010. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Glen Barclay and Joseph Siracusa (1976) Australian American Relations Since 1945. p.35-49. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Sydney. ISBN 978-0-03-900122-3

- ^ Glen Barclay and Joseph Siracusa (1976) p.35

- ^ See Adrian Tame and F.P.J Robotham (1982) Maralinga; British A-Bomb, Australian legacy. p.179 Fontana Books, Melbourne. ISBN 0-00-636391-1

- ^ E.M. Andrews (1979) A History of Australian Foreign Policy. P.144 Longman Cheshire, Melbourne. ISBN 978-0-582-68253-5

- ^ Glen Barclay and Joseph Siracusa (1976) p.63

- ^ Also see Desmond Ball (1980) A suitable piece of real estate; American Installations in Australia. Hale and Iremonger. Sydney. ISBN 978-0-908094-47-9

- ^ See discussion on the role of ANZUS in Australia's commitment to the Vietnam War in Paul Ham (2007) Vietnam; The Australian War. p.86-7 Harper Collins Publishers, Sydney. ISBN 978-0-7322-8237-0

- ^ a b "In office – Harold Holt – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ a b "In office – John Gorton – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "rugby.com.au | MANDELA TO HONOUR ANTI-APARTHEID WALLABIES OF 71". Aru.rugby.com.au. Archived from the original on 14 September 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ Geoffrey Bolton (1990) p.229-230

- ^ Richard White (1981) Inventing Australia; Images and Identity, 1688–1980. p.169 George Allen and Unwin, Sydney. ISBN 978-0-86861-035-1

- ^ Anne Pender (March 2005) The Australian Journal of Politics and History. "The Mythical Australian: Barry Humphries, Gough Whitlam and new nationalism" The Mythical Australian: Barry Humphries, Gough Whitlam and "new nationalism" | Australian Journal of Politics and History, The|Find Articles at BNET

- ^ Richard White (1981) p.170

- ^ "John Gorton – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ a b "Vietnam War 1962–75 | Australian War Memorial". Awm.gov.au. 11 January 1973. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "4102.0 - Australian Social Trends, 1994". Abs.gov.au. 27 May 1994. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Peacock made 'bird of paradise' chief". News.ninemsn.com.au. Archived from the original on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "In office – Gough Whitlam – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Nauru". State.gov. 31 August 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ Gough Whitlam, Bankstown Speech.13 November 1972. Cited in Sally Warhaft (Ed.) (2004) Well may we say… The Speeches that made Australia. p.178-9 Blac Inc, Melbourne. ISBN 978-1-86395-277-4

- ^ Geoffrey Bolton (1990) p.215-216.

- ^ Jan Bassett (1986) p273-4

- ^ Gough Whitlam (1985) p.315

- ^ "In office – Gough Whitlam – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Archived from the original on 19 April 2013. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ There are numerous books on the Whitlam dismissal. For example, see Paul Kelly's November 1975: The Inside Story of Australia's Greatest Political Crisis. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86373-987-0.

- ^ "In office – Malcolm Fraser – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ "Senator Bob Brown". Abc.net.au. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- ^ The First Australians: A Fair Deal for a Dark Race par SBS TV 2008.

- ^ The First Australians: A Fair Deal for a Dark Race par SBS TV 2008.

- ^ Address by John Gorton at the Conference of Commonwealth and State Ministers Responsible for Aboriginal Affairs - 12 July 1968; pmc.gov.au

- ^ Address by John Gorton at the Conference of Commonwealth and State Ministers Responsible for Aboriginal Affairs - 12 July 1968; pmc.gov.au

- ^ Background to Abstudy; Australian Government Department of Social Services

- ^ 'Our history', Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) website, http://aiatsis.gov.au/about-us/our-history Archived 28 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 29 April 2014

- ^ Geoffrey Bolton (1990) p.193 and 195

- ^ Mark McKenna, Captive Republic: A History of Republicanism in Australia 1788–1996 (1997)

- ^ "Australians and Peacekeeping | Australian War Memorial". Awm.gov.au. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

Further reading

References

- Bambrick, Susan ed. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Australia (1994)

- Basset, Jan. The Oxford Illustrated Dictionary of Australian History (1998)

- Davison, Graeme, John Hirst, and Stuart Macintyre, eds. The Oxford Companion to Australian History (2001) online at many academic libraries; also excerpt and text search

- Day, David. Claiming a Continent: A New History of Australia (2001);

- Dennis, Peter, Jeffrey Grey, Ewan Morris, and Robin Prior. The Oxford Companion to Australian Military History. 1996

- Jupp, James, ed. The Australian People: An Encyclopedia of the Nation, its People and their Origins (2nd ed. 2002) 960pp excerpt and text search

- Macintyre, Stuart. A Concise History of Australia. (2009) excerpt and text search

- O'Shane, Pat et al. Australia: The Complete Encyclopedia (2001)

- Robinson GM, Loughran RJ, and Tranter PJ. Australia and New Zealand: economy, society and environment.(2000)

- Shaw, John, ed. Collins Australian Encyclopedia (1984)

- Welsh, Frank. Australia: A New History of the Great Southern Land (2008)

History

- Bennett, Bruce et al. The Oxford Literary History of Australia (1999)

- Bennett, Tony, and David Carter. Culture in Australia: Policies, Publics and Programs (2001) excerpt and text search

- Bolton, Geoffrey. The Oxford History of Australia: Volume 5: 1942–1995. The Middle Way (2005)

- Bramble, Tom. Trade Unionism in Australia: A History from Flood to Ebb Tide (2008) excerpt and text search

- Bridge, Carl ed., Munich to Vietnam: Australia's Relations with Britain and the United States since the 1930s, Melbourne University Press 1991

- Carey, Hilary. Believing in Australia: A Cultural History of Religions (1996)

- Edwards, John. Curtin's Gift: Reinterpreting Australia's Greatest Prime Minister, (2005) online edition Archived 23 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Firth, Stewart. Australia in International Politics: An Introduction to Australian Foreign Policy (2005) online edition

- Grant, Ian. A Dictionary of Australian Military History – from Colonial Times to the Gulf War (1992)

- Hearn, Mark, Harry Knowles, and Ian Cambridge. One Big Union: A History of the Australian Workers Union 1886–1994 (1998)

- Hutton, Drew, and Libby Connors. History of the Australian Environment Movement (1999) excerpt and text search

- Kelly, Paul. The End of Certainty: Power, Politics and Business in Australia, (1994), history of the 1980s

- Kleinert, Sylvia. and Margo Neale. The Oxford Companion to Aboriginal Art and Culture (2001)

- Lee, David. Search for Security: The Political Economy of Australia's Postwar Foreign and Defence Policy (1995)

- Lowe, David. Menzies and the 'Great World Struggle': Australia's Cold War 1948–54 (1999) online edition

- Martin, A. W. Robert Menzies: A Life (2 vol 1993–99), online at ACLS e-books

- McIntyre, Stuart. The History Wars (2nd ed. 2004), historiography

- McLachlan, Noel. Waiting for the Revolution: A History of Australian Nationalism (1989)

- McLean, David. "Australia in the Cold War: a Historiographical Review." International History Review (2001) 23(2): 299–321. ISSN 0707-5332

- McLean, David. "From British Colony to American Satellite? Australia and the USA during the Cold War", Australian Journal of Politics & History (2006) 52 (1), 64–79. Rejects satellite model. online at Blackwell-Synergy

- Megalogenis, George. The Longest Decade (2nd ed. 2009), politics 1990–2008

- Moran, Albert. Historical Dictionary of Australian Radio and Television (2007)

- Moran, Anthony. Australia: Nation, Belonging, and Globalization Routledge, 2004 online edition Archived 23 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Murphy, John. Harvest of Fear: A History of Australia's Vietnam War (1993)

- Watt, Alan. The Evolution of Australian Foreign Policy 1938–1965, Cambridge University Press, 1967

- Webby, Elizabeth, ed. The Cambridge Companion to Australian Literature (2006)