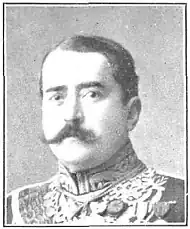

Rodrigo Figueroa y Torres

Rodrigo Figueroa y Torres | |

|---|---|

Photographed by Franzen, c. 1909 | |

| Ambassador of Spain to the Holy See | |

| In office 1905–1906 | |

| Preceded by | Manuel Aguirre de Tejada |

| Succeeded by | Emilio de Ojeda y Perpiñán |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Rodrigo Figueroa y Torres 24 October 1866 Madrid, Spain |

| Died | 1 June 1929 (aged 62) Madrid, Spain |

| Parent |

|

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Civil Governor of Madrid |

Rodrigo Figueroa y Torres (24 October 1866 – 1 June 1929) was a Spanish politician during the Restoration and Civil Governor of Madrid in 1909.[1]

He studied medicine, but he is best known for being a politician and a wide-ranging artist, standing out especially as a sculptor, winning various mentions in Fine Arts Exhibitions.[2] He was thus a truly versatile person, a doctor interested in sculpture, painting, diplomacy, and even held the noble title of Duke of Tovar.[1][2][3]

Early life

Rodrigo Figueroa y Torres was born in Madrid on 24 October 1866. He was the son of Ignacio Figueroa y Mendieta and Ana de Torres, Viscountess of Irueste.[2][4] Among his siblings were the younger brother of José (Viscount of Irueste), Gonzalo (the 1st Duke of Las Torres), and Álvaro (the Count of Romanones).[4][3] He was part of one of the most influential families in Spain during the Restoration period.[5]

In 1893, his mother gave him the title of Marquess of Tovar, which his friend King Alfonso XIII converted into a Duchy of Spain in 1906.[2] Figueroa was thus the first Duke of Tovar, created by Royal Decree in 1906,[1] a title that he inherited from his mother.[4]

Career in Arts

A disciple of the sculptor Agustín Querol,[1][2] Figueroa presented a portrait of his father in a marble bust to the National Exhibition of Fine Arts of 1895, for which he was awarded an honorable mention.[1] He presented a Greek Water Carrier to the Exhibition of 1899, which won him a third-class medal.[1] Finally, in the Exhibition of 1901, he obtained a second-class medal consideration with his Monument Project to Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer.[1]

Figueroa was president of the Círculo de Bellas Artes.[1][2] He also stood out as a playwright, translating several successful works, such as those of Pierre Loti, and being for many years a royal commissioner, equivalent to director, at the Teatro Real.[1][2] In 1902, he was granted the title of Grandee of Spain by Alfonso XIII.[1] In 1904 he acquired the satirical magazine Gideón.[3]

On 19 October 1908, Figueroa was elected full academician of architecture at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando,[1][2] and in 1910 he was responsible for answering the sculptor Eduardo Barrón's admission speech to that corporation.[1] In 1920, he was already a member of the Sculpture Jury at the National Exhibition of Fine Arts.[1]

Political career

Figueroa was elected deputy to the Cortes for the district of Brihuega as a member of the Liberals in the 1893 elections,[2][6][7][3] and then repeating the feat for Tolosa in 1898.[3] He was thus a deputy for Guadalajara in 1893 and for Gipuzkoa in 1898.[1]

A councilor of the City Council of Madrid, and senator in his own right since 1902,[1][8] he became a Romanonist representative in the upper house.[2][3] In 1909, with Segismundo Moret's entry into office in October, he was named civil governor of Madrid, after several years as a councilor.[1][3] He was replaced in November by Federico Requejo.[3]

Figueroa was also an Ambassador of Spain to the Holy See from 1905 to 1906.[1][2]

Sporting career

Figueroa was a great athlete, standing out in his youth as a fencing champion, and even though he never rode in horse races, he was a great fan of such, so much so that he became the owner of a horse racing club that trained at the Hipódromo de la Castellana.[2] The horses belonged to the family and they ran indifferently with colors from one or the other (Mejorada, Villamejor, Tovar, widow of Villamejor). He only declared colors in 1894 and kept them until he died in 1929.[2] He always kept some horses in training, but never the volume of his father and brother.[2] His greatest successes as an owner were achieved in the 1900 Grand National horse race, which was held in Liverpool and in the 1901 Vitelotte.[2]

Later life

Figueroa was also an enterprising businessman; In 1918, he made an important renovation on his agricultural estate Villa Cumbre, in San Sebastián, which in 2003 was declared an asset of cultural interest. In the year of his death, he had acquired a cattle ranch in Portugal.[1]

Personal life

In September 1891, he married Amelia de Bermejillo y Martínez-Negrete (1872–1944), a lady-in-waiting to Queen Victoria Eugenie of Battenberg.[4] She was a daughter of Pío de Bermejillo y Ibarra and María Ignacia Martínez Negrete de Alba. Together, they are the parents of:[9]

- Ignacio de Figueroa y Bermejillo (1892–1953), 2nd Duke of Tovar; he was succeeded in the titles by his cousin Agustín de Figueroa Alonso-Martínez.[10]

- Joaquín de Figueroa y Bermejillo (b. 1893)

- Cristina de Figueroa y Bermejillo (b. 1894)

- María de la Piedad de Figueroa y Bermejillo (b. 1894), who married José Antonio del Arco y Cubas, 3rd Count of Arcentales.[11]

- Rodrigo de Figueroa y Bermejillo (1896–1938)

- Alfonzo de Figueroa y Bermejillo (1897–1968), who married María de Valvanera de Melgar y Rojas, a daughter of Mauricio Melgar y Alvarez de Abreú, 6th Marquess of Regalía.[9]

- Rafael de Figueroa y Bermejillo (1903–1982), who married María de la Concepción de Melgar y Rojas, also a daughter of Mauricio Melgar y Alvarez de Abreú, 6th Marquess of Regalía.[9]

Figueroa died in his hometown on 1 June 1929, at the age of 62.[4][7] He was succeeded by his son: Ignacio, the 2nd Duke of Tovar and a Great Gentleman of Spain with exercise and servitude of King Alfonso XIII.[4]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Rodrigo Figueroa y Torres – Real Academia de la Historia" [Rodrigo Figueroa y Torres – Royal Academy of History]. dbe.rah.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Rodrigo de Figueroa y Torres. Duque/marqués de Tovar 1866 –1929". equijar.com (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Persona – Figueroa Torres, Rodrigo (1866–1929)". pares.mcu.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f "Rodrigo de Figueroa y Torres". gw.geneanet.org (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ Gortázar 1989, p. 252.

- ^ Moreno Luzón 1996, p. 147.

- ^ a b "FIGUEROA Y TORRES RODRIGO . 38. Elecciones 5.3.1893 – Congreso de los Diputados" [FIGUEROA Y TORRES RODRIGO. 38. Elections 5.3.1893 – Congress of Deputies]. www.congreso.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Figueroa y Torres, Rodrigo de. Marquis of Tovar". www.senado.es (in Spanish). Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Salcedo, Juan Miguel Soler (24 April 2020). Nobleza Española. Grandezas Inmemoriales 2ª edición (in Spanish). Vision Libros. p. 440. ISBN 978-84-17755-62-1. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "Figueroa Bermejillo, Ignacio (1892-1953)". pares.mcu.es. Ministry of Culture. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

- ^ "Intervención de Hacienda de la provincia de Guadalajara" (PDF). Gaceta de Madrid. 3 (186): 65. 5 July 1906. Retrieved 29 July 2025.

Bibliography

- Gortázar, Guillermo [in Spanish] (1989). "Las dinastías españolas de fundidores de plomo de Marsella: don Luis Figueroa y Casaus (1781–1853)" (PDF). Haciendo historia: homenaje al profesor Carlos Seco. pp. 251–260. ISBN 84-7491-246-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-19.

- Moreno Luzón, Javier (1996). "El conde de Romanones y el caciquismo en Castilla (1888–1923)". Investigaciones Históricas: Época Moderna y Contemporánea. 16: 145–166. ISSN 0210-9425.