1470s

The 1470s decade ran from January 1, 1470, to December 31, 1479.

| Millennia |

|---|

| 2nd millennium |

| Centuries |

| Decades |

| Years |

| Categories |

|

Events

1470

January–March

- January 9 – Grand Prince Jalsan of Joseon becomes the new King of Korea upon the death of his uncle, King Yejong. Jalisan takes the regnal name of King Seongjong.[1].[2]

- January 21 – Jacquetta of Luxembourg, mother of England's Queen Consort Elizabeth Woodville and mother-in-law of King Edward IV, is cleared of allegations of witchcraft that had been made against her in 1469 by a follower of the rebel Earl of Warwick.[3]

- March 12 – Wars of the Roses in England – At the Battle of Losecoat Field, the House of York (supporters of King Edward IV) defeats the House of Lancaster (supporters of the former King Henry VI, led by Sir Robert Welles).[4] Welles is captured and confesses that he had been hired by the Earl of Warwick and by King Edward's brother, George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence to overthrow the King. Warwick and Clarence flee England and Welles is beheaded.[5]

- March 20 – The Battle of Nibley Green is the last fought between the private armies of feudal magnates in England.[6]

April–June

- April 5 – At Srinagar in the Kashmir Sultanate, the Sultan Zayn al-Abidin the Great dies after a reign of almost 52 years, and his succeeded by his son, Prince Haji Khan, who takes the name Haider Shah Miri on his proclamation as Sultan on May 12.[7]

- May 6 – Yun Chaun becomes the new Chief State Councillor (Yonguijong, equivalent to a prime minister as head of government) of Korea, when he is appointed by King Seongjong to replace Hong Yunsŏng.

- May 15 – Charles VIII of Sweden, who has served three terms as King of Sweden, dies. Sten Sture the Elder proclaims himself Regent of Sweden the following day.[8]

- June 1 – Sten Sture is recognised as the new King of Sweden by the estates.[9]

July–September

- July 12 – During the Ottoman–Venetian War, the Ottomans capture the Greek island of Euboea, territory of the Republic of Venice, after a four week siege of the fortified city of Negroponte by the Sultan Mehmed II.[10]

- August 20 – Battle of Lipnic: Stephen the Great defeats the Volga Tatars of the Golden Horde, led by Ahmed Khan.

- September 13 – A rebellion orchestrated by King Edward IV of England's former ally, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, forces the King to flee England to seek support from his brother-in-law, Charles the Bold of Burgundy.[11]

October–December

- October 3 – The Earl of Warwick releases King Henry VI of England from imprisonment in the Tower of London, and restores him to the throne.[12]

- November 28 – Emperor Lê Thánh Tông of Đại Việt launches a naval expedition against Champa, beginning the Cham–Annamese War.[13]

- December 18 – Lê Thánh Tông leads the Đại Việt army into Champa, conquering the country in less than three months.[13]

Date unknown

- The Pahang Sultanate is established at Pahang Darul Makmur (in modern-day Malaysia).

- The first contact occurs between Europeans and the Fante nation of the Gold Coast, when a party of Portuguese land and meet with the King of Elmina.

- Johann Heynlin introduces the printing press into France and prints his first book this same year.

- In Tonga, in or around 1470, the Tuʻi Tonga Dynasty cedes its temporal powers to the Tuʻi Haʻatakalaua Dynasty, which will remain prominent until about 1600.

- Between this year and 1700, 8,888 witches are tried in the Swiss Confederation; 5,417 of them are executed.

- Sir George Ripley dedicates his book, The Compound of Alchemy, to the King Edward IV of England.

1471

January–March

- January 4 – Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy agrees to help Edward IV regain the English throne from King Henry VI.

- January 17 – Portuguese navigators João de Santarém and Pedro Escobar discover the uninhabited island of Príncipe (now part of the nation of São Tomé and Príncipe ). They initially call it "Ilha de Santo Antão" because they land it on the feast day of Saint Anthony.

- January 22 – At age 15, Prince João of Aviz, the eldest son of King Afonso V, marries his 12-year-old first cousin, Leonor de Avis. Both are grandchildren of King Duarte I of Portugal.[14]

- January – Portuguese navigators João de Santarém and Pedro Escobar reach the gold-trading centre of Elmina on the Gold Coast of west Africa,[15] and explore Cape St. Catherine, two degrees south of the equator, so that they begin to be guided by the Southern Cross constellation. They also visit Sassandra on the Ivory Coast.

- February 10 – Albrecht III Achilles becomes the new Elector of Brandenburg upon the abdication of his older brother, Friedrich II, who had guided the electorate since 1440.

- February 24 – In what is now south Vietnam, the Champa–Dai Viet War begins when the Dai Viet Emperor Lê Thánh Tông sends 500 warships to block the Champa Kingdom's Bay of Sa Ky, while another 30,000 troops block all entrances to the capital city of Vijaya at what is now the Quảng Ngãi Province. The Me Can citadel in Quang Na falls two days later and the Vietnamese advance.[16]

- March 22 – The Empire of Dai Viet in north Vietnam triumphs over the Champa Kingdom of south Vietnam after Dai Viet Emperor Le Thanh Tong ignores the offer of Champa King Tra Toan to surrender Vijaya.[17] After the city walls are breached, King Tra Toan, his family and 30,000 other Chams are captured as prisoners, while over 60,000 other Chams are killed.[18] Another 40,000 residents who did not die in the fighting are executed.[19]

- March 15 – With the help of a group of mercenaries lent to him by Charles the Bold of Burgundy, the Yorkist King Edward IV returns to England to reclaim his throne, landing near Hull, after having departed from Holland on March 11.[20]

April–June

- April 14 – At the Battle of Barnet, Edward defeats the Lancastrian army under Warwick, who is killed.[21]

- May 4 – At the Battle of Tewkesbury, King Edward defeats a Lancastrian army led by Queen Margaret and her son, Edward of Westminster the Prince of Wales. Edward, Prince of Wales, kis killed in the battle.[22]

- May 12 – The siege of London is attempted by hundreds of supporters of England's House of Lancaster, who are attempting to free the former King Henry VI from imprisonment in the Tower of London. Led by Thomas Neville, the Lancastrians set cannons up on the south bank of the Thames and attempt to bombard London, but is unable to break the defense put up by Londoners led by Edward Woodville, Lord Scales, and the attack fails after three days.[23]

- May 21 – King Edward IV celebrates his victories with a triumphal parade on his return to London. The captured Queen Margaret is paraded through the streets. On the same day Henry VI of England is murdered in the Tower of London[24], eliminating all Lancastrian opposition to the House of York.

- May 27 – Two months after the death of King George of Poděbrady, the Diet of Bohemian nobles meets at Kutná Hora and elects Vladislaus Jagiello as the new King of Bohemia.[25] The papal legate, Lorenzo Roverella, Bishop of Ferrara, declares the election void with the approval of Pope Paul II, and endorses Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, to be the new King of Bohemia, which the Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire refuses to approve.[26]

- June 26 – Edward of York, the 7-month-old son of King Edward IV of England, is created Prince of Wales, two months after his father has regained the throne.[27]

July–September

- July 14 – At the Battle of Shelon, the forces of Muscovy defeat the Republic of Novgorod.

- July 26 – Pope Paul II dies of a heart attack. at age 54 after a reign of almost seven years, leaving the Roman Catholic Church papacy vacant.

- August 6 – Eleven days after the death of Pope Paul II, the papal conclave begins in Rome with 18 of the 25 cardinals present. On the initial vote, with 12 needed to win, |Basilios Bessarion of Greece gets six, and |Guillaume d'Estouteville of France and Niccolò Fortiguerra of Italy receive three each.[28]

- August 9 – Cardinal Francesco della Rovere, who received no votes in the initial round of balloting in the papal conclave, receives 13 votes and is elected as the new Pontiff of the Roman Catholic Church. He takes the regnal name of Pope Sixtus IV to become the 212th pope.[28]

- August 22 –

- King Afonso V of Portugal conquers the Moroccan town of Arzila.

- Vladislav Jagellion is crowned as King of Bohemia at Prague.[26]

- August 29 – The Portuguese occupy Tangier, after its population flees the city.

- September 21 – After making his way to Prague, convening a session of the Bohemian Diet and making making promises to members of the nobility, Hungarian King Matthias Corvinus receives vows of loyalty from more than 50 Bohemian nobles, who agree to support Matthias's claim to be King of Bohemia rather than to accept the rule of Prince Casimir of Poland.[29]

- September 22 – After being tracked down by King Edward IV and taken prisoner at Southampton, the rebel Thomas Neville is beheaded at Middleham Castle in his native Yorkshire.[30]

October–December

- October 2 – Eleven days after Hungary's King Matthias is supported to be King of Bohemia, Prince Casimir of Poland, a younger son of King Casimir IV (who is later canonized as a Roman Catholic saint) leads an army on an invasion of Bohemia and begins a war against Hungary.[31]

- October 10 – Battle of Brunkeberg in Stockholm, Sweden: The forces of Regent of Sweden Sten Sture the Elder, with the help of farmers and miners, repel an attack by Christian I, King of Denmark.

- November 12 – Shah Suwar, the ruler of the independent Ottoman Governor of the semi-independent Anatolian Turk Beylik of Dulkadir is defeated by the army of the Egyptian Mamluk General Yashbak min Mahdi in a battle at Kars, sustaining more than 300 soldiers lost and losing most of his lands in what is now southeastern Turkey. After fleeing to the castle of Zamantu for refuge, Suwar is cornered again by Yashbak and surrenders on June 4, 1472, and executed two months later.[32]

- November 25 – Nicolò Tron is elected as the new Doge of the Republic of Venice, 15 days after the death of the Doge Cristoforo Moro, who had governed the Republic since 1461..[33]

- December 25 – The Great Comet of 1472 is first observed from Earth passing in front of the constellation of Virgo. The comet is recorded by astronomers in Korea and by the German astronomers Regiomontanus and Bernhard Walther, and will come within 6.5 million miles of Earth, the closest in recorded history that a great comet approaches. The comet is visible for 59 days, disappearing after March 1.[34]

Date unknown

- Pachacuti Inca Yupanqui of the Inca Empire dies, and is succeeded by his son Topa Inca Yupanqui.

- Moorish exiles from Spain, led by Moulay Ali Ben Moussa Ben Rached El Alami, found the city of Chefchaouen in the north of Morocco.

- Marsilio Ficino's translation of the Corpus Hermeticum into Latin, De potestate et sapientia Dei, is published.

1472

January–March

- January 22 – The Great Comet of 1472 passes within 0.07 astronomical units of Earth (6.507 million miles or 10.472 million km), the closest approach in recorded history for a great comet[35]

- February 20 – Orkney and Shetland are returned by Norway to Scotland, as a result of a defaulted dowry payment.[36]

- March 4 – A mount of piety is established in Siena (Italy), origin of Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena, the world's oldest surviving retail bank.[37]

- March 11 – The Great Comet of 1472 is observed from the Earth for the last time as it flies away from Earth in the direction of the constellation of Cetus.[35]

April–June

- April 11 – The first printed edition of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy is published in Foligno.[38]

- May 27 – An alliance agreement is signed between Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy and Nicholas I, Duke of Lorraine, with Charles pledging his daughter, Mary of Burgundy, to marry Nicholas. The agreement comes at the same time that King Ferdinand I of Naples had been negotiating the engagement of Mary of Burgundy to Frederick, prince of Naples.[39]

- May 31 – The Treaty of Prenzlau is signed between Albert III, Elector of Brandenburg, and the two Dukes of Pomerania, Eric II and Wartislaw X, surrendering the Duchy of Pomerania-Stettin to Albert's control and ending the eight-year-long War of the Succession of Stettin.[40]

- June 1 – Sophia Palaiologina is married by proxy to the ruler of Russia, Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow, in a ceremony at St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, with his trusted emissary Ivan Fryazin serving as the proxy.[41]

- June 4 – Shah Suwar, formerly the ruler much of southeastern Turkey as prince of the Beylik of Dulkadir, surrenders to the Egyptian Mamluk General Yashbak min Mahdi after an 11-day siege.[42] He is brought out of the Castle of Zamantu, restrained by a robe with a metal collar with chains and his guards are unable to rescue him. Suwar's older brother, Shah Budak, is returned to the throne of Dulkadir

- June 16 – Volterra, a town in the Republic of Florence in Italy, surrenders after a siege of 25 days by Florentine soldiers under the command of Federico da Montefeltro. Because the town had rebelled against the power of Lorenzo de' Medici, da Montefeltro allows his soldiers on June 18 to pillage Volterra and to commit rape and murder of its citizens.[43]

- June – Leonardo da Vinci is admitted as a master in his own right to the artists' Guild of Saint Luke in Florence. An entry is made in the register of the Compagnia di San Luca reading "Anno Domini 1472— Leonardo, son of Ser Piero da Vinci, painter, to pay the sum of 6 sol, for the whole month of June 1472, for the remittance of his debt to the Company until July 1472... and to pay for the whole of November 1472, 5 sol due on 18 October 1472."[44]

July–September

- July 3 – The Cathedral and Metropolitical Church of Saint Peter in York, England, commonly known as York Minster, is declared complete and consecrated.[45]

- August 19 – King Edward IV summons the members of the English Parliament to assemble at Westminster on October 6.

- September 11 – The Treaty of Chateaugiron is concluded between King Edward IV of England and the Duchy of Brittany, providing for an English invasion of either Gascony or Normandy by April 1, 1473.[46]

October–December

- October 6 – King Edward IV of England gives royal assent to the Statute of Westminster 1472 which requires, effective immediately, a tax of four bow staves per every tun (252 wine gallons) of cargo brought in by a ship to an English port.[47] The Statute is passed to remedy a shortage of yew wood, from which longbows are made, following the issuing of an edict in 1470 requiring compulsory training for soldiers to use the longbow.[48]

- October 28 – The Catalan Civil War comes to an end as Barcelona surrenders to King Juan II of Aragon with the signing of the Capitulation of Pedralbes by the rebel leader Hugh Roger III of Pallars Sobirà, guaranteeing the rights of the Principality of Catalonia in return for allegiance to the Kingdom of Aragon.[49]

- November 5 – Duke Nicholas of Lorraine and Duke Charles of Burgundy agree that the engagement between Nicholas and Charles's daughter can be called off without jeopardizing the alliance between the two duchies.[39]

- December 31 – The city council of Amsterdam prohibits snowball fights: "Neymant en moet met sneecluyten werpen nocht maecht noch wijf noch manspersoon." ("No one shall throw with snowballs, neither men nor (unmarried) women.")

Undated

- The Kingdom of Fez ruling the modern nation of Morocco, is founded by the Wattasid dynasty with Sultan Abu Abd Allah al-Sheikh Muhammad ibn Yahya as its first ruler.[50]

- An extensive slave trade begins in modern Cameroon as the Portuguese sail up the Wouri River and Fernão do Po claims the central-African islands Bioko and Annobón for Portugal.id=vtZtMBLJ7GgC&q=Terra+do+Bacalhao&pg=PA447|title=Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580|first1=Bailey Wallys|last1=Diffie|first2=Boyd C.|last2=Shafer|first3=George Davison|last3=Winius|year=1977|publisher=U of Minnesota Press|isbn=9780816607822}}

- The first printing of Thomas à Kempis' The Imitation of Christ (De Imitatione Christi) is made in Augsburg after Kempis's death in 1471[51] it will reach 100 editions and translations by the end of the century.[52]

- Johannes de Sacrobosco's De sphaera mundi (written c. 1230) is first published in Ferrara, the first printed astronomical book.

- Pietro d'Abano's medical texts Conciliator differentiarum quae inter philosophos et medicos versantur and De venenis eorumque remediis (written before 1315) are first published.

1473

January–March

- January 1 – The uninhabited island of Annobón, off of the coast of West Africa, is claimed by Portuguese explorers who name in honor of the New Year.[53] A year later, it becomes the home of enslaved Africans who either marry or work of Portuguese citizens, or sold.

- January 9 – Pope Sixtus IV lifts the order of interdict that had been placed by Pope Paul II on the late Bohemian King George of Poděbrady and his sons, granting absolution, after the sons convert to the Roman Catholic faith.[54]

- January 22 – Muhammad Jiwa Shah becomes the new Sultan of Kedah, an absolute monarchy at the south of the Malay Peninsula and now part of Malaysia, upon the death of his father, Ataullah Muhammad Shah.

- February 12 – The first complete inside edition of Avicenna's The Canon of Medicine (Latin translation) is published in Milan.

- March 6 – The original University of Trier is founded in the Electorate of the Paletine in what is now Germany, 18 years after the Pope had granted the Archbishop of Trier, Jakob von Sierck, the papal dispensation to create a university. After 365 years, the university is closed in 1798, but re-established 172 years later in 1970.

- March 17 – An heir to the throne of Scotland is born to Queen Margaret and King James III. Prince James of the House of Stewart will become King James IV of Scotland at the age of 15 in 1488.

April–June

- April 5 – Philip I, leader of the Russian Orthodox Church as Patriarch of Moscow since 1464, dies after a reign of almost nine years.

- May 7 – Pope Sixtus IV appoints eight clerics to the College of Cardinals, the most in his career, the most since December 18, 1439 when 17 were appointed by Pope Eugene IV.

- May 28 – The Earl of Oxford, commander of what remains of the Lancastrians during the Wars of the Roses against the Yorkists and King Edward IV of England, makes an unsuccessful attempt to land an army at Essex at the village of St Osyth.

- June 29 – Gerontius, Bishop of Kolomna is appointed as the new Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church.

July–September

- July 10 – James II, King of Cyprus, dies after a reign of nine years. In that his widow, the Queen Consort Catherine, is eight months pregnant with the couple's son, she becomes Queen Regent and the throne is deemed to remain vacant until the child is born.

- July 27 – René II, Count of Vaudémont becomes the new Duke of Lorraine, at the time an independent principality within the Holy Roman Empire, upon the death of his cousin, Nicholas I. after his mother, the Duchess Yolande gives up her rights to the throne.

- August 6 – King James III of Cyprus becomes the de jure monarch of Cyprus from the moment he is born, 27 days after the death of his father, King James II, although the rule of Cyprus is carried out by his mother, Catherine, Queen regent.[55] King James III lives for only one year and 20 days before dying on August 26, 1474.[56]

- August 11 – At the Battle of Otlukbeli, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II defeats the White Sheep Turkmens, led by Uzun Hasan.[57]

- August 13 – Nicolò Marcello is elected as the new Doge of Venice following the July 28 death of Nicolo Tron.

- September 7 – In Germany, Gerhard VII, Duke of Jülich-Berg destroys the Tomburg Castle near Wormersdorf in what is now the German state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The one-day shelling of the castle with cannons takes place after a dispute with the Lord of Tomburg, Friedrich von Sombreff. The castle is never rebuilt and the ruins remain more than 550 years later.[58]

- September 30 –

- The Earl of Oxford, John de Vere, seizes St Michael's Mount in Cornwall and defends it for the next five months against 6,000 troops of King Edward IV.[59]

- The Trier Conference begins in the German city of Trier as the Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor and Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy make a grand entry into the city of Trier for a meeting of central European leaders to respond to the threat of an invasion by the Ottoman Empire.[60]

October–December

- October 1 – Johannes Hennon publishes the medical treatise Commentarii in Aristotelis libros Physicorum.

- October 7 – At Trier, Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, hosts an elaborate banquet for the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II and various prince-electors of the electorates within the Empire, ostensibly to work towards a common union of nations to begin a new crusade against the Ottomans, but offends most of his guests because of his arrogant ambition. On October 18, Albert IV, Duke of Bavaria becomes the first of the guests to walk out of the conference.

- October 31 – The Trier Conference breaks up after Charles the Bold fails to persuade the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick to help Charles become King of the Romans or to enter into an alliance against King Loouis XI of France. Frederick II instead proposes an alliance between the Empire, Burgundy, and France. Charles threatens to leave unless he can secure an alliance by a treaty marriage.[61]

- November 4 – The negotiators for Burgundy and the Holy Roman Empire tentatively agree on creating a Kingdom of Burgundy, ruled by Charles the Bold, that would become a member of the Empire and that would include Burgundy, Holland, Luxembourg, Savoy, Lorraine and other parts of what are now the Netherlands, Belgium and France.[62] A coronation ceremony for Charles as King of Burgundy is tentatively scheduled to take place on November 25.

- November 20 – The Battle of Vodna Stream, near Râmnicu Sărat, ends after two days in what is now Romania, Stephen the Great, Prince of Moldavia, routs the army of Wallachia, commanded by Prince Radu the Handsome. Prince Radu then flees to Dâmbovița.[63]

- November 23 – Prince Stephen of Moldavia begins the siege of Dâmbovița Fortress, where Wallachia's Prince Radu Prince of Wallachia]], has taken refuge in a war between the two monarchs. Prince Radu escapes during the night, leaving behind his wife, his daughter and his treasury, and the fortress surrenders the next day.[63]

- November 25 – On the day set for the scheduled coronation at Trier of Charles the Bold as King of Burgundy, Charles learns that the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick had changed his mind and left overnight, and that the ceremony will never take place.[61]

- December 7 – The first-known printed book about child care, Kinderbüchlein, is published by German physician Bartholomäus Metlinger.[64]

- December 23 – Radu II returns as Prince of Wallachia one month after having been deposed briefly by Basarab the Old.

Date unknown

- Stephen the Great of Moldavia refuses to pay tribute to the Ottomans. This will attract an Ottoman invasion in 1475, resulting in the greatest defeat of the Ottomans so far.

- Axayacatl, Aztec ruler of Tenochtitlan, invades the territory of the neighboring Aztec city of Tlatelolco. The ruler of Tlatelolco is killed and replaced by a military governor; Tlatelolco loses its independence.

- Possible discovery of the island of "Bacalao" (possibly Newfoundland off North America) by Didrik Pining and João Vaz Corte-Real.

- The city walls and defensive moat are built in Celje, Slovenia.

- Almanach cracoviense ad annum 1474, an astronomical wall calendar, is published in Kraków, the oldest known printing in Poland.[65]

- Florentine physician Marsilio Ficino becomes a Catholic priest.

- Possible date – Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye is the first book to be printed in English, by William Caxton, in Bruges.

1474

January–December

- January 6 – At the age of one year and nine months, Bianca Maria Sforza, the daughter of the Duke of Milan, Galeazzo Maria Sforza, is betrothed to the 9-year-old, Duke of Savoy, Philibert I, as part of an alliance between the two independent Italian duchies.[66]

- February 7 – The Hungarian town of Varad is attacked by an Ottoman Empire army of 7,000 cavalry, commanded by General Mihaloğlu Ali Bey, and its inhabitants are taken prisoner. Bunyitay Vincze (1883–1884).[67]

- February 21 – The Treaty of Ófalu is signed between the Kingdom of Poland and the Kingdom of Hungary.

- February 28 – The Treaty of Utrecht puts an end to the Anglo-Hanseatic War, restoring the status quo that had existed before the war, with the Kingdom of England and the states of the Hanseatic League agreeing to respect each others trading rights.[68]

- March 19 – The Senate of the Republic of Venice enacts the Venetian Patent Statute, one of the earliest patent systems in the world.[69] New and inventive devices, once put into practice, have to be communicated to the Republic to obtain the right to prevent others from using them. This is considered the first modern patent system.[70]

- April 24 – The members of the Hungarian nobility ratify the treaty with Poland after King Matthias had given his assent on February 27.[71]

- July 25 – By signing the Treaty of London, Charles the Bold of Burgundy agrees to support Edward IV of England's planned invasion of France.[72]

- December 12 – Upon the death of Henry IV of Castile, a civil war ensues between his designated successor Isabella I of Castile, and her niece Juana, who is supported by her husband, Afonso V of Portugal. Isabella wins the civil war after a lengthy struggle, when her husband, the newly crowned Ferdinand II of Aragon, comes to her aid.

Date unknown

- Marsilio Ficino completes his book Theologia Platonica (Platonic Theology).

- Axayacatl defeats the Matlatzinca of the Toluca Valley.

1475

January–December

- January 10 – Battle of Vaslui (Moldavian–Ottoman Wars): Stephen III of Moldavia defeats the Ottoman Empire, which is led at this time by Mehmed the Conqueror of Constantinople.

- July 4 – Burgundian Wars: Edward IV of England lands in Calais, in support of the Duchy of Burgundy against France.[73]

- August 29 – The Treaty of Picquigny ends the brief war between France and England.

- November 13 – Burgundian Wars – Battle on the Planta: Forces of the Old Swiss Confederacy are victorious against those of the Duchy of Savoy, near Sion, Switzerland.

- November 14 – The original Landshut Wedding takes place, between George, Duke of Bavaria, and Hedwig Jagiellon.

- December – The Principality of Theodoro falls to the Ottoman Empire,[74] arguably taking with it the final territorial remnant of the successor to the Roman Kingdom after nearly 2,228 years of Roman civilization since the legendary Founding of Rome in 753 BC.

Date unknown

- Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye is the first book to be printed in English, by William Caxton in Bruges (or 1473–74?).

- Rashi's commentary on the Torah is the first dated book to be printed in Hebrew, in Reggio di Calabria.[75]

- Conrad of Megenberg's book, Buch der Natur, is published in Augsburg.[76]

- In Wallachia, Radu cel Frumos loses the throne (for the last time), and is again replaced by Basarab Laiotă.

1476

January–December

- March 1 – Battle of Toro (War of the Castilian Succession): Although militarily inconclusive, this ensures the Catholic Monarchs the Crown of Castile, forming the basis for modern-day Spain.

- March 2 – Battle of Grandson (Burgundian Wars): Swiss forces defeat Burgundy.[77]

- June 22 – Battle of Morat (Burgundian Wars): The Burgundians suffer a crushing defeat, at the hands of the Swiss.

- July 26 – Battle of Valea Albă (Moldavian–Ottoman Wars): The Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II defeats Stephen III of Moldavia.

- November 26 – Vlad the Impaler declares himself reigning Voivode (Prince) of Wallachia for the third and last time. He is killed on the march to Bucharest, probably before the end of December. His head is sent to his old enemy, Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II.

Date unknown

- Leonardo da Vinci is acquitted on charges of sodomy, after which he disappears from the historical record for two years.

- Axayacatl, sixth Tlatoani of Tenochtitlán, is defeated by the Tarascans of Michoacán.

- Goyghor Mosque is built by Musa ibn Haji Amir and his son, Majlis Alam.[78]

1477

January–December

- January 5 – Battle of Nancy: Charles the Bold of Burgundy is again defeated, and this time is killed; this marks the end of the Burgundian Wars.[79]

- February? – Volcano Bardarbunga erupts in Iceland, with a VEI of 6.

- February 11 – Mary of Burgundy, the daughter of Charles the Bold, is forced by her disgruntled subjects to sign the Great Privilege, by which the Flemish cities recover all the local and communal rights which have been abolished by the decrees of the dukes of Burgundy, in their efforts to create a centralized state in the Low Countries.

- February 27 – Uppsala University is founded, becoming the first university in Sweden and all of Scandinavia.[80]

- August 19 – Mary of Burgundy marries Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, in Ghent, bringing her Flemish and Burgundian lands into the Holy Roman Empire, and detaching them from France.[81]

- November 18 – William Caxton produces Earl Rivers' translation into English of Dictes or Sayengis of the Philosophres, at his press in Westminster, the first full-length book printed in England on a printing press.[82]

Undated

- Ivan III of Russia marches against the Novgorod Republic, marking the beginning of Russian Colonialism.

- Giovanni Pico della Mirandola starts to study canon law, at the University of Bologna.

- Thomas Norton (alchemist) writes Ordinall of Alchemy.

- The first edition of The Travels of Marco Polo is printed.

1478

January–December

- January 14 – Novgorod surrenders to Ivan III, Grand Prince of Moscow.

- January 15 – Richard of Shrewsbury, Duke of York is married to Anne de Mowbray, 8th Countess of Norfolk in England.

- February 18 – George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, convicted of treason against his older brother Edward IV of England, is privately executed in the Tower of London.

- April 26 – The Pazzi family attacks Lorenzo de' Medici, and kills his brother Giuliano, during High Mass in Florence Cathedral.[83]

- May 14 – The Siege of Shkodra in Albania begins.

- November – Eskender succeeds his father Baeda Maryam as Emperor of Ethiopia, at the age of six.

- November 1 – The Spanish Inquisition begins.

- December 28 – Battle of Giornico: Swiss troops defeat the Milanese.

Date unknown

- Grand Duchy of Moscow devolved from the Golden Horde.

- Lorenzo de' Medici becomes sole ruler of Florence.

- The Demak Sultanate gains independence from Majapahit, after a civil war.

- The Fourth Siege of Krujë, Albania by the Ottoman Empire, concludes and results in the town's capture, after the failure of three prior sieges.

- Vladislav II of Bohemia makes peace with Hungary.

- Possibly the first reference to cricket, in "criquet", as discovered in France by Rowland Bowen in the 20th century. It has been dismissed by some (most notably John Major) and presaged with Edward II's "Creag" (1300) by others.

- Mondino de Liuzzi's Anathomia corporis humani, the first complete published anatomical text, is first printed (in Padua).

1479

January–December

- January 20 – Ferdinand II ascends the throne of Aragon, and rules together with his wife Isabella I, Queen of Castile, over most of the Iberian Peninsula.

- January 25 – The Treaty of Constantinople is signed between the Ottoman Empire and Republic of Venice, ending sixteen years of war between the two powers; Venice will cede Negroponte, Lemnos and Shkodër, and pay an annual sum of 10,000 gold ducats.[84]

- April 25 – Ratification of the Treaty of Constantinople in Venice ends the Siege of Shkodra after fifteen months, and brings all of Albania under the Ottoman Empire.

- May 13 – Christopher Columbus, an experienced mariner and successful trader in the thriving Genoese expatriate community in Portugal, marries Felipa Perestrelo Moniz (Italian on her father's side), and receives as dowry her late father's maps and papers, charting the seas and winds around the Madeira Islands, and other Portuguese possessions in the Ocean Sea.

- August 7 – Battle of Guinegate: A French army sent to invade the Netherlands is defeated by Maximilian of Austria.

- September 4 – The Treaty of Alcáçovas (also known as the Treaty or Peace of Alcáçovas-Toledo) is signed between the Catholic Monarchs of Castile and Aragon on one side, and the King of Portugal and his son on the other side, ending the four-year War of the Castilian Succession.

- October 13 – Battle of Breadfield (Hungarian: Kenyérmezei csata, Turkish: Ekmek Otlak Savaşı): The army of the Kingdom of Hungary, led by Pál Kinizsi and István Báthory, defeats that of the Ottoman Empire in Transylvania, Hungary, leaving at least 10,000 Turkish dead.

Ongoing

- The plague breaks out in Florence.[85]

- Johann Neumeister prints a new edition of Juan de Torquemada's Meditations, or the Contemplations of the Most Devout.[86]

Significant people

Births

1470

- January 1 – Magnus I, Duke of Saxe-Lauenburg, German noble (d. 1543)

- February 16 – Eric I, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Prince of Calenberg (1491–1540) (d. 1540)

- April 7 – Edward Stafford, 2nd Earl of Wiltshire (d. 1498)

- April 9 – Giovanni Angelo Testagrossa, Italian composer (d. 1530)

- May 20 – Pietro Bembo, Italian cardinal (d. 1547)[87]

- June 30 – Charles VIII of France (d. 1498)[88]

- July 13 – Francesco Armellini Pantalassi de' Medici, Italian Catholic cardinal (d. 1528)

- July 20 – John Bourchier, 1st Earl of Bath, English noble (d. 1539)

- July 30 – Hongzhi Emperor of China (d. 1505)

- August 4

- Bernardo Dovizi, Italian Catholic cardinal (d. 1520)

- Lucrezia de' Medici, Italian noblewoman (d. 1553)

- October 2

- George I of Münsterberg, Imperial Prince, Duke of Münsterberg and Oels, Graf von Glatz (d. 1502)

- Isabella of Aragon, Queen of Portugal, daughter of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon (d. 1498)

- Isabella of Aragon, Duchess of Milan, daughter of Alfonso II of Naples (d. 1524)

- October 10 – Selim I, Sultan of the Ottoman Empire (d. 1520)

- October 15 – Konrad Mutian, German humanist (d. 1526)

- November 2 – King Edward V of England, the elder of the "Princes in the Tower" (d. c. 1483)[89]

- November 28 – Wen Zhengming, artist in Ming dynasty China (d. 1559)

- December 5 – Willibald Pirckheimer, German humanist (d. 1530)

- date unknown

- Juan Díaz de Solís, Spanish navigator and explorer (d. 1516)

- Tang Yin, Chinese painter (d. 1524)

- Polydore Vergil, Urbinate/English historian (d. 1555)

- probable

- Matthias Grünewald, German painter (d. 1528)

- Hayuya, Taino chief (d. unknown)

- Hugh Latimer, Protestant martyr (d. 1555)

1471

- April 6 – Margaret of Hanau-Münzenberg, German noblewoman (d. 1503)

- May 21 – Albrecht Dürer, German artist, writer and mathematician (d. 1528)[90]

- July 15 – Eskender, Emperor of Ethiopia (d. 1494)

- July 22 – Anthony Kitchin, British bishop (d. 1563)

- July 31 – Jan Feliks "Szram" Tarnowski, Polish nobleman (d. 1507)

- August 27 – George, Duke of Saxony (d. 1539)

- September 8 – William III, Landgrave of Hesse (d. 1500)

- October 7 – King Frederick I of Denmark and Norway (d. 1533)

- date unknown

- John Forrest, English martyr and friar (d. 1538)

- Edmund de la Pole, 3rd Duke of Suffolk (d. 1513)

1472

- January 17 – Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Italian condottiero and Duke of Urbino (d. 1508)

- February 15 – Piero di Lorenzo de' Medici, ruler of Florence (d. 1503)

- March 28 – Fra Bartolomeo, Italian artist (d. 1517)[91]

- April 5 – Bianca Maria Sforza, Pavian-born Holy Roman Empress as consort to Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor (d. 1510)[92]

- April 10 – Margaret of York, English princess (d. 1472)[93]

- May 31 – Érard de La Marck, prince-bishop of Liège (d. 1538)

- August 11 – Nikolaus von Schönberg, German Catholic cardinal (d. 1537)

- October 19 – John Louis, Count of Nassau-Saarbrücken (d. 1545)

- October 31 – Wang Yangming, Chinese Neo-Confucian scholar (d. 1529)

- November 24 – Pietro Torrigiano, Italian sculptor of the Florentine school (d. 1528)

- December 10 – Anne de Mowbray, 8th Countess of Norfolk (d. 1481)

- date unknown

- Lucas Cranach the Elder, German painter (d. 1553)[94]

- Alfonsina Orsini, Regent of Florence (d. 1520)

- Barbro Stigsdotter, Swedish noblewoman and heroine (d. 1528)

1473

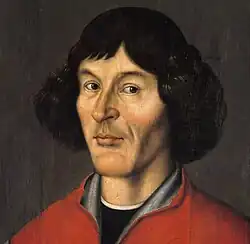

- February 19 – Nicolaus Copernicus, Polish astronomer and mathematician (d. 1543)[95]

- February 25 – Al-Mutawakkil Yahya Sharaf ad-Din, Imam of the Zaidi state in Yemen (d. 1555)

- March 3 – Asakura Sadakage, 9th head of the Asakura clan (d. 1512)

- March 14 – Reinhard IV, Count of Hanau-Münzenberg (1500–1512) (d. 1512)

- March 16 – Henry IV, Duke of Saxony (1539–1541) (d. 1541)

- March 17 – King James IV of Scotland, King of Scots from 11 June 1488 to his death (d. 1513)[96]

- April 2 – John Corvinus, Hungarian noble (d. 1504)

- July 4 – Matilda of Hesse, German noblewoman (d. 1505)[97]

- July 6 – James III of Cyprus, son of James II of Cyprus and Catherine Cornaro, king of Cyprus (d. 1474)

- July – Maddalena de' Medici, Italian noble (d. 1528)[98]

- August 14 – Margaret Pole, 8th Countess of Salisbury (d. 1541)

- August 17 – Richard, Duke of York, one of the Princes in the Tower (d. 1483)[99]

- August 25 – Margaret of Münsterberg, Duchess consort and regent of Anhalt (d. 1530)

- September 2 – Ercole Strozzi, Italian poet (d. 1508)[100]

- September 23 – Thomas Lovett III, High Sheriff of Northamptonshire (d. 1542)

- September 24 – Georg von Frundsberg, German knight and landowner (d. 1528)

- October 26 – Friedrich of Saxony, Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights (d. 1510)

- date unknown – Thomas Howard, 3rd Duke of Norfolk, English Tudor politician (d. 1555)

- probable

- Jean Lemaire de Belges, Walloon poet and historian (d. 1525)

- Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales, only son of Richard III of England (d. 1484)

- Cecilia Gallerani, principal mistress of Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan (d. 1536)

1474

- January 7 – Thihathura II of Ava (d. 1501)

- March 21 – Angela Merici, Italian religious leader and saint (d. 1540)

- May 5

- Juan Diego, Roman Catholic Saint from Mexico (d. 1548)

- Giovanni Stefano Ferrero, Italian cardinal (d. 1510)

- May 18 – Isabella d'Este, Marquise of Mantua (d. 1539)

- August 6 – Luigi de' Rossi, Italian cardinal (d. 1519)

- September 8 – Ludovico Ariosto, Italian poet (d. 1533)[101]

- October 6 – Luigi d'Aragona, Italian cardinal (d. 1518)

- October 7 – Bernhard III, Margrave of Baden-Baden (d. 1536)

- October 13 – Mariotto Albertinelli, High Renaissance Italian painter of the Florentine school (d. 1515)

- November 7 – Lorenzo Campeggio, Italian Cardinal (d. 1539)

- November 8 – Francesco Vettori, Italian diplomat (d. 1539)

- November 11 – Bartolomé de las Casas, Spanish Dominican friar, historian, and social reformer (d. 1566)

- December 24 – Bartolomeo degli Organi, Italian musician (d. 1539)

- date unknown

- Anacaona, Taino queen and poet (d. 1503)

- Juan Diego, Mexican Catholic saint (d. 1548)

- Giacomo Pacchiarotti, Italian painter (d. 1539 or 1540)

- Cuthbert Tunstall, English bishop and diplomat (d. 1559)

- Humphrey Kynaston, English highwayman (d. 1534)

- probable

- Sebastian Cabot, Venetian explorer (d. c. 1557)[102]

- Edward Guilford, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports of England (d. 1534)

- Stephen Hawes, English poet (d. c. 1521)

- Sir John Seymour, English courtier (d. 1536)

- Perkin Warbeck, pretender to the throne of England (d. 1499)

1475

- January 9 – Crinitus, Italian humanist (d. 1507)

- January 29 – Giuliano Bugiardini, Italian painter (d. 1555)

- February 25 – Edward Plantagenet, 17th Earl of Warwick, last male member of the House of York (d. 1499)

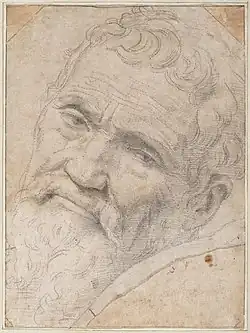

- March 6 – Michelangelo Buonarroti, Italian sculptor (d. 1564)[103]

- March 12 – Luca Gaurico, Italian astrologer (d. 1558)

- March 30 – Elisabeth of Culemborg, German noble (d. 1555)

- June 29 – Beatrice d'Este, duchess of Bari and Milan (d. 1497)

- September 6

- Artus Gouffier, Lord of Boissy, French nobleman and politician (d. 1519)

- Sebastiano Serlio, Italian Mannerist architect (d. 1554)

- September 8 – John Stokesley, English prelate (d. 1539)[104]

- September 13 or April 1476 – Cesare Borgia, illegitimate son of Pope Alexander VI (approximate date; d. 1507)

- October 20 – Giovanni di Bernardo Rucellai, Italian Renaissance man of letters (d. 1525)

- November 2 – Anne of York, seventh child of King Edward IV of England and Elizabeth Woodville (d. 1511)[105]

- November 28 – Anne Shelton, elder sister of Thomas Boleyn (d. 1556)

- December 11 – Pope Leo X (d. 1521)[106]

- December 24 – Thomas Murner, German satirist (d. c. 1537)

- date unknown

- Valerius Anshelm, Swiss chronicler

- Vasco Núñez de Balboa, Spanish conquistador (approximate date; d. 1519)

- Gendun Gyatso, 2nd Dalai Lama (d. 1541)

- probable

- Thomas West, 9th Baron De La Warr (d. 1554)

- Margaret Drummond, mistress of James IV of Scotland (d. 1502)

- Pierre Gringoire, French poet and playwright (d. 1538)

- Filippo de Lurano, Italian composer (d. 1520)

- Gunilla Bese, Finnish noble and fiefholder (d. 1553)

1476

- January 14 – Anne St Leger, Baroness de Ros, English baroness (d. 1526)[107]

- March 12 – Anna Jagiellon, Duchess of Pomerania, Polish princess (d. 1503)

- May 2 – Charles I, Duke of Münsterberg-Oels, Count of Kladsko, Governor of Bohemia and Silesia (d. 1536)

- May 19 – Helena of Moscow, Grand Duchess consort of Lithuania and Queen consort of Poland (d. 1513)

- June 28 – Pope Paul IV (d. 1559)[108]

- July 17 – Adrian Fortescue, English Roman Catholic martyr (d. 1539)[109]

- July 21

- Alfonso I d'Este, Duke of Ferrara (d. 1534)

- Anna Sforza, Italian noble (d. 1497)[110]

- July 22 – Zhu Youyuan, Ming Dynasty politician (d. 1519)

- August 28 – Kanō Motonobu, Japanese painter (d. 1559)

- September 11 – Louise of Savoy, French regent (d. 1531)[111]

- October 1 – Guy XVI, Count of Laval (d. 1531)

- October 26 – Yi Ki, Korean philosopher (d. 1552)

- November 23 – Yeonsangun of Joseon, King of Korean Joseon Dynasty (d. 1506)

- December 13 – Lucy Brocadelli, Dominican tertiary and stigmatic (d. 1544)

- date unknown – Juan Sebastián Elcano, Spanish explorer (d. 1526)

1477

- January 13 – Henry Percy, 5th Earl of Northumberland (d. 1527)

- January 14 – Hermann of Wied, German Catholic archbishop (d. 1552)

- January 16 – Johannes Schöner, German astronomer and cartographer (d. 1547)

- January 25 – Anne of Brittany, sovereign duchess of Brittany, queen of Charles VIII of France (d. 1514)[112]

- March 20 – Jerome Emser, German theologian (d. 1527)

- June 22 – Thomas Grey, 2nd Marquess of Dorset, English noble (d. 1530)

- July 4 – Johannes Aventinus, Bavarian historian and philologist (d. 1534)

- July 12 – Jacopo Sadoleto, Italian cardinal (d. 1547)

- September 1 – Bartolomeo Fanfulla, Italian mercenary (d. 1525)

- September 19 – Ferrante d'Este, Ferrarese nobleman and condottiero (d. 1540)

- September 21 – Matthäus Zell, German Lutheran pastor (d. 1548)

- date unknown – István Báthory, Hungarian nobleman (d. 1534)

- probable

- Giorgione, painter in Italian High Renaissance (d. 1510)[113]

- Girolamo del Pacchia, Italian painter (d. 1533)

- Lambert Simnel, pretender to the throne of England (d. c. 1534)

- Il Sodoma, Italian painter (d. 1549)

- Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire, English diplomat (d. 1539)

1478

- February 3 – Edward Stafford, 3rd Duke of Buckingham (d. 1521)

- February 7 – Thomas More, English statesman and humanist (d. 1535)[114]

- May 26 – Pope Clement VII (d. 1534)[115]

- June 30 – John, Prince of Asturias, Son of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile (d. 1497)

- July 2 – Louis V, Elector Palatine (1508–1544) (d. 1544)

- July 8 – Gian Giorgio Trissino (d. 1550)

- July 13 – Giulio d'Este, illegitimate son of Italian noble (d. 1561)

- July 15 – Barbara Jagiellon, Duchess consort of Saxony and Margravine consort of Meissen (1500–1534) (d. 1534)

- July 22 – King Philip I of Castile (d. 1506)

- August – Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Spanish historian (d. 1557)

- December 6 – Baldassare Castiglione, Italian courtier and writer (d. 1529)

- date unknown

- Jacques Dubois, French anatomist (d. 1555)

- Giovanna d'Aragona, Duchess of Amalfi, Italian regent (d. 1510)

- Girolamo Fracastoro, Italian physician (d. 1553)

- Visconte Maggiolo, Italian navigator and cartographer (d. 1530)

- Katharina von Zimmern, Swiss sovereign abbess (d. 1547)

- probable

- Thomas Ashwell, English composer

- Madeleine Lartessuti, French shipper and banker (d. 1543)

1479

- March 12 – Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours (d. 1516)

- March 13 – Lazarus Spengler, German hymnwriter (d. 1534)

- March 20 – Ippolito d'Este, Italian Catholic cardinal (d. 1520)

- March 25 – Vasili III of Russia, Grand Prince of Moscow (d. 1533)

- May 3 – Henry V, Duke of Mecklenburg (d. 1552)

- May 5 – Guru Amar Das, third Sikh Guru (d. 1574)

- May 12 – Pompeo Colonna, Italian Catholic cardinal (d. 1532)

- June 14 – Giglio Gregorio Giraldi, Italian scholar and poet (d. 1552)

- June 15 – Lisa del Giocondo, Florentine noblewoman believed to be the subject of the Mona Lisa (d. 1542)

- August 14 – Catherine of York, English princess, aunt of Henry VIII (d. 1527)[116]

- September 17 – Celio Calcagnini, Italian astronomer (d. 1541)

- October 28 – John Gage, English courtier of the Tudor period (d. 1556)

- November 6

- Joanna of Castile, Queen of Philip I of Castile, daughter of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon (d. 1555)

- Philip I, Margrave of Baden (d. 1533)

- December – Ayşe Hafsa Sultan, Ottoman Valide Sultan (d. 1534)

- date unknown

- Johann Cochlaeus, German humanist and controversialist (d. 1552)

- Vallabhacharya, Indian founder of the Vallabha sect of Hinduism (d. 1531)

- probable – Henry Stafford, 1st Earl of Wiltshire (d. 1522)

Deaths

1470

- January 2 – Heinrich Reuß von Plauen, Grand Master of the Teutonic Order

- March 20 – Thomas Talbot, 2nd Viscount Lisle, English nobleman killed at the Battle of Nibley Green (b. c.1449)[6]

- May 15 – Charles VIII of Sweden (b. 1409)[117]

- August 31 – Frederick II, Count of Vaudémont (b. c.1428)[118]

- October 18 – John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester, Lord High Treasurer (b. 1427)

- November 23 – Gaston, Prince of Viana (b. 1444)

- December 16 – John II, Duke of Lorraine (b. 1425)

- date unknown

- Domenico da Piacenza, Italian dancing master (b. 1390)

- Pal Engjëlli, Albanian Catholic clergyman (b. 1416)

- probable – Jacopo Bellini, Italian painter (b. 1400)

1471

- January 18 – Emperor Go-Hanazono of Japan (b. 1418)

- February 10 – Frederick II, Margrave of Brandenburg (b. 1413)

- February 21 – John of Rokycan, Archbishop of Prague (b. c. 1396)

- March 14 – Thomas Malory, English author (b. c. 1405)

- March 22 – George of Poděbrady, first elected King of Bohemia (b. 1420)

- April 14

- John Neville, 1st Marquess of Montagu (b. 1431)

- Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, English nobleman, known as "the Kingmaker" (b. 1428)[119]

- May 4 – Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales (in battle) (b. 1453)[120]

- May 6

- Edmund Beaufort, 4th Duke of Somerset (executed) (b. 1438)[121]

- Thomas Tresham, Speaker of the House of Commons

- May 21 – King Henry VI of England (murdered in prison) (b. 1421)[122]

- July 25 – Thomas à Kempis, German monk and writer (b. 1380)

- July 26 – Pope Paul II (b. 1417)[123]

- August 20 – Borso d'Este, Duke of Ferrara (b. 1413)

- November 8 – Louis II, Landgrave of Lower Hesse (1458–1471) (b. 1438)

- December 17 – Infanta Isabel, Duchess of Burgundy (b. 1397)

- date unknown

- Pachacuti, Inca emperor (b. 1438)

- P'an-Lo T'ou-Ts'iuan, last independent King of Champa

- Shin Sawbu, queen regnant of Hanthawaddy in southern Burma (b. 1394)

1472

- March 30 – Amadeus IX, Duke of Savoy (b. 1435)

- April 25 – Leon Battista Alberti, Italian painter, poet and philosopher (b. 1404)[124]

- May 24 – Charles de Valois, Duke de Berry, French noble (b. 1446)

- May 30 – Jacquetta of Luxembourg, English duchess, daughter of Pierre de Luxembourg (b. 1416)[125]

- June 4 – Nezahualcoyotl, Aztec poet (b. 1402)

- July 15 – Johann II of Nassau-Saarbrücken, Count of Nassau-Saarbrücken (1429–1472) (b. 1423)

- July 25 – Charles of Artois, Count of Eu, French military leader (b. 1394)

- November 18 – Basilios Bessarion, Latin Patriarch of Constantinople (b. 1403)

- December 11 – Margaret of York, English princess (b. 1472)[93]

- date unknown – Afanasy Nikitin, Russian traveller

- probable

- Thomas Boyd, Earl of Arran

- Hayne van Ghizeghem, Flemish composer (b. c. 1445)

- Michelozzo, Italian architect and sculptor (b. c. 1396)

1473

- January 24 – Conrad Paumann, German composer (b. c. 1410)

- February 23 – Arnold, Duke of Guelders (b. 1410)

- April 3 – Alessandro Sforza, Italian condottiero (b. 1409)

- April 15 – Yamana Sōzen, Japanese daimyō and monk (b. 1404)

- May 8 – John Stafford, 1st Earl of Wiltshire, English politician (b. 1420)

- June 6 – Hosokawa Katsumoto, Japanese nobleman (b. 1430)

- June 28 – John Talbot, 3rd Earl of Shrewsbury, English nobleman (b. 1448)[126]

- July 10 – James II of Cyprus (b. c. 1440)

- November 26 – Diego Fernández de la Cueva, 1st Viscount of Huelma

- October – Contessina de' Bardi, politically active Florentine woman (b. 1390)

- December 24 – John Cantius, Polish scholar and theologian (b. 1390)

- date unknown

- Ewuare I, Oba of Benin

- Jean Jouffroy, French prelate and diplomat (b. c. 1412)

- Nicholas I, Duke of Lorraine (b. 1448)

- Sigismondo Polcastro, Paduan physician and natural philosopher (b. 1384)

- probable – Marina Nani, Venetian dogaressa (b. c. 1400)

- probable – Patriarch Gennadios II of Constantinople (b. c. 1400)

1474

- January 3 – Pietro Riario, Catholic cardinal (b. 1447)

- March 22 – Iacopo III Appiani, Prince of Piombino (b. 1422)

- April 14 – Anna of Brunswick-Grubenhagen, daughter of Duke Eric I of Brunswick-Grubenhagen (b. 1414)

- April 30 – Queen Gonghye, Korean royal consort (b. 1456)

- May 4 – Alain de Coëtivy, Catholic cardinal (b. 1407)

- May 9

- Alfonso Vázquez de Acuña, Roman Catholic prelate, Bishop of Jaén and Bishop of Mondoñedo (b. 1474)

- Peter von Hagenbach, Alsatian knight and ruler (b. 1423)

- May 11 – John Stanberry, Bishop of Hereford[127]

- May 14 – Ch'oe Hang, Korean politician (b. 1409)

- July 5 – Eric II, Duke of Pomerania-Wolgast (b. 1418)

- July 9 – Isotta degli Atti, Italian Renaissance woman (b. 1432)

- July 18 – Mahmud Pasha Angelović, Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire (b. 1420)

- August 1 – Walter Blount, 1st Baron Mountjoy, English politician (b. 1416)

- August 16 – Ricciarda of Saluzzo (b. 1410)

- August 26 – James III of Cyprus (b. 1473)

- September 21 – George I, Prince of Anhalt-Dessau (b. 1390)

- October 1 – Juan Pacheco, Spanish noble and politician (b. 1419)

- November – William Canynge, English merchant (b. c. 1399)

- November 27 – Guillaume Dufay, Flemish composer (b. 1397)[128]

- December 1 – Nicolò Marcello, Doge of Venice (b. 1397)

- December 11 – King Henry IV of Castile (b. 1425)[129]

- December 16 – Ali Qushji, Ottoman astronomer and mathematician (b. 1403)

- date unknown

- Gomes Eannes de Azurara, Portuguese chronicler (b. c. 1410)

- Antoinette de Maignelais, French royal favorite (b. 1434)

- Gendun Drup, 1st Dalai Lama (b. 1391)

- probable

- Walter Frye, English composer

- Jehan de Waurin, French chronicler

1475

- January – Radu cel Frumos, Voivoid of Wallachia (b. c. 1437)

- February 3 – John IV, Count of Nassau-Siegen (b. 1410)

- March – Simon of Trent, Italian saint, subject of a blood libel

- March 20 – Georges Chastellain, Burgundian chronicler and poet[130]

- May 20 – Alice Chaucer, Duchess of Suffolk (born c.1404)[131]

- June 13 – Joan of Portugal, Queen of Castile (b. 1439)

- September 6 – Adolph II of Nassau, Archbishop of Mainz (b. c. 1423)

- December 10 – Paolo Uccello, Italian painter (b. 1397)

- date unknown

- Theodorus Gaza, Greek scholar, one of the leaders of the revival of learning in the 15th century (b. c. 1400)

- Theodosius, Metropolitan of Moscow

- Masuccio Salernitano, Italian poet (b. 1410)

1476

- January 14

- John de Mowbray, 4th Duke of Norfolk (b. 1444)

- Anne of York, Duchess of Exeter, Duchess of York, second child of Richard Plantagenet (b. 1439)

- March 1 – Imagawa Yoshitada, 9th head of the Imagawa clan (b. 1436)

- March 10 – Richard West, 7th Baron De La Warr (b. 1430)

- March – John I Ernuszt, Ban of Slavonia

- June 8 – George Neville, English archbishop and statesman (b. c. 1432)

- July 6 – Regiomontanus, German astronomer (b. 1436)

- September 8 – Jean II, Duke of Alençon, son of John I of Alençon and Marie of Brittany (b. 1409)

- November 28 – James of the Marches, Franciscan friar

- December

- Vlad III the Impaler, Prince of Wallachia (b. 1431)[132]

- Isabel Neville, Duchess of Clarence, English noblewoman (b. 1451)[133]

- December 12 – Frederick I, Elector Palatine (b. 1425)

- December 26 – Galeazzo Maria Sforza, Duke of Milan (assassinated) (b. 1444)

- Clara Hätzlerin, German scribe (b. 1430)

1477

- January 2

- Franzone, Italian assassin (executed)[134]

- Gerolamo Olgiati, Italian assassin (executed)[134]

- Carlo Visconti, Italian assassin (executed)[134]

- January 5 – Charles the Bold, Duke of Burgundy (in battle) (b. 1433)[79]

- January 6 – Jean VIII, Count of Vendôme

- January 15 – Adriana of Nassau-Siegen, consort of Count Philip I of Hanau-Münzenberg (b. 1449)

- April – William Hugonet, former chancellor of Burgundy (executed)

- June 27 – Adolf, Duke of Guelders and Count of Zutphen (1465–1471) (b. 1438)

- August 4 – Jacques d'Armagnac, Duke of Nemours

- August 11 – Latino Orsini, Italian Catholic cardinal (b. 1411)

- December 19 – Maria of Mangup, Princess-consort of Moldavia

- June 1 – Charlotte de Brézé, French countess (b. 1446)

1478

- February 1 – Cristoforo della Rovere, Italian Catholic cardinal (b. 1434)

- February 18 – George Plantagenet, 1st Duke of Clarence, brother of Edward IV of England and Richard III of England (executed) (b. 1449)[135]

- April 26 – Giuliano de' Medici, son of Piero di Cosimo de' Medici (assassinated) (b. 1453)

- June 12 – Ludovico III Gonzaga, Marquis of Mantua (b. 1412)[136]

- August 23 – Yolande of Valois, Duchess consort of Savoy (b. 1434)

- August 28 – Donato Acciaioli, Italian scholar (b. 1428)

- November 8 – Emperor Baeda Maryam I of Ethiopia (b. 1448)

- date unknown – Aliodea Morosini, Venetian dogaressa

1479

- January 18 – Louis IX, Duke of Bavaria (b. 1417)

- January 20 – King John II of Aragon (b. 1397)

- February – Antonello da Messina, Italian painter (b. c. 1430)

- February 10 – Catherine of Cleves, duchess consort regent of Guelders (b. 1417)

- February 12 – Eleanor of Navarre, queen regnant of Navarre (b. 1426)

- April 24 – Jorge Manrique, Spanish poet (b. 1440)

- June 11 – John of Sahagún, Spanish Augustinian friar, priest and saint (b. 1419)

- September 10 – Jacopo Piccolomini-Ammannati, Italian Catholic cardinal (b. 1422)

- September 18 – Fulk Bourchier, 10th Baron FitzWarin, English baron (b. 1445)

- November 6 – James Hamilton, 1st Lord Hamilton

- date unknown

- Johanne Andersdatter Sappi, Danish noble (b. 1400)

- Ólöf Loftsdóttir, politically active Icelandic woman (b. c. 1410)

References

- ^ Han, Hee-Sook (2004). "Women's Life during the Chosŏn Dynasty" (PDF). International Journal of Korean History. 6: 159. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Jeong, Yoo-Cheol (February 21, 2014). 예종의 갑작스런 승하로 왕이 된 성종, 조선 조 첫 수렴청정이 시작되다. Korean Spirit. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office, Volume 3 p. 53 Web. 17 November 2014.

- ^ Michael Rayner (2004). English Battlefields: An Illustrated Encyclopaedia. Tempus. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-7524-2978-6.

- ^ Richardson, Douglas (2011). Everingham, Kimball G. (ed.). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families. Vol. IV (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City: Douglas Richardson. p. 307. ISBN 978-1460992708.

- ^ a b Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society (2007). Transactions - Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society. Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society.

- ^ Hasan, Mohibbul (2005). Kashmir Under the Sultans. Aakar Books. p. 42. ISBN 978-81-87879-49-7.

- ^ "Sten Sture the Elder". Biografiskt lexikon för Finland (in Swedish). Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland.

- ^ Bain, Robert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 1051–1052.

- ^ Tansel, Selahattin. Fatih Sultan Mehmed'in Siyasi ve Âskerî Faaliyetleri (PDF). p. 204.

- ^ Wilkinson, Bertie (1969). The later Middle Ages in England, 1216–1485. Harlow: Longmans. p. 293. ISBN 0-5824-8265-8.

- ^ Weir, Alison (2011). Lancaster And York: The Wars of the Roses. Random House. p. 177. ISBN 978-1-4464-4917-2.

- ^ a b Zottoli, Brian A. (2011), Reconceptualizing Southern Vietnamese History from the 15th to 18th Centuries: Competition along the Coasts from Guangdong to Cambodia, University of Michigan, p. 78

- ^ Sabugosa, Conde de (1921). A rainha D. Leonor, 1458-1525 (PDF) (First ed.). Lisbon: Portugalia Editora. pp. 40–43.

- ^ Wilks, Ivor (1997). "Wangara, Akan and Portuguese in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries". In Bakewell, Peter (ed.). Mines of Silver and Gold in the Americas. Aldershot: Ashgate. pp. 1–39.

- ^ Taylor, K.W. (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-521-87586-8.

- ^ Sun, Laichen (2006). "Chinese Gunpowder Technology and Đại Việt, ca. 1390–1497". In Anthony Reid; Tran Nhung Tuyet (eds.). Viet Nam: Borderless Histories. Cambridge: University of Wisconsin Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-316-44504-4.

- ^ Maspero, Georges (2002). The Champa Kingdom. White Lotus Co., Ltd. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-9-747-53499-3.

- ^ Zottoli, Brian A. (2011). Reconceptualizing Southern Vietnamese History from the 15th to 18th Centuries: Competition along the Coasts from Guangdong to Cambodia. University of Michigan. p. 79.

- ^ "English History", by Albert Frederick Pollard, in Encyclopaedia Britannica (Cambridge University Press, 1910) p.519

- ^ Burne, Alfred (1950). "The Battle of Barnet, April 14th, 1471". The Battlefields of England. London: Methuen and Company. p. 108. OCLC 3010941. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ^ "English Heritage Battlefield Report: Tewkesbury 1471" (PDF). English Heritage. 1995. pp. 2–3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2020. Retrieved 2010-04-24.

- ^ Tait, James. . Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 40. pp. 304=306.

- ^ Weir, Alison (2008). Britain's Royal Family. Vintage Books. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-0995-3973-5.

- ^ Macek, Josef (1998). "The monarchy of the estates". In Teich, Mikuláš (ed.). Bohemia in History. Cambridge University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-521-43155-7.

- ^ a b Teke, Zsuzsa (1981). "A középkori magyar állam virágzása és bukása, 1301–1526: 1458–1490 [Flourishing and Fall of Medieval Hungary, 1301–1526: 1458–1490]". In Solymosi, László (ed.). Magyarország történeti kronológiája, I: a kezdetektől 1526-ig [Historical Chronology of Hungary, Volume I: From the Beginning to 1526] (in Hungarian). Akadémiai Kiadó. p. 292. ISBN 963-05-2661-1.

- ^ l Previous Princes Archived 14 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Prince of Wales official website. Retrieved on 15 July 2013

- ^ a b Burkle-Young, Francis A. 1998. "The election of Pope Sixtus IV (1471)".

- ^ Kubinyi, András (2004). "Adatok a Mátyás-kori királyi kancellária és az 1464. évi kancelláriai reform történetéhez" [On the history of the Royal Chancellery in the reign of Matthias Corvinus and of the 1464 reform of the chancellery] (PDF). Publicationes Universitatis Miskolciensis. Sectio Philosophica (in Hungarian). IX (1). Universitatis Miskolciensis: 92–93. ISSN 1219-543X.

- ^ Santiuste, David (2011). Edward IV and the Wars of the Roses. Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1848845497.

- ^ Bartl, Július; Čičaj, Viliam; Kohútova, Mária; Letz, Róbert; Segeš, Vladimír; Škvarna, Dušan (2002). Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, Slovenské Pedegogické Nakladatel'stvo. p. 52. ISBN 0-86516-444-4.

- ^ Yinanç, Refet (1989). Dulkadir Beyliği (in Turkish). Ankara: Turkish Historical Society Press. pp. 71–73. ISBN 9751601711.

- ^ Niccolò Tron, enciclopedia Treccani.

- ^ Seargeant, David A. (2009). The Greatest Comets in History. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-38709-513-4.

- ^ a b Seargeant, David A. (2009). The Greatest Comets in History. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-38709-513-4.

- ^ Royal Historical Society (Great Britain) (1939). Guides and Handbooks. Royal Historical Society. p. 208.

- ^ @banca_mps (2014-03-04). "4 marzo 1472 – 4 marzo 2014 Buon compleanno, Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ Kleinhenz, Christopher (2004). Medieval Italy: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Routledge. p. 360. ISBN 0-415-93930-5.

- ^ a b Calmet, Augustin (29 April 2014). "Histoire ecclésiastique et civile de Lorraine,Dom Augustin Calmet, Chez Jean-Baptiste Cusson, Nancy, 1728 , pages 892-894". Google livres.

- ^ Ingo Materna, Wolfgang Ribbe, Kurt Adamy, Brandenburgische Geschichte, Akademie Verlag, 1995, p.206, ISBN 3-05-002508-5, ISBN 978-3-05-002508-7

- ^ William Miller, Essays on the Latin Orient (Cambridge University Press, 1921) pp. 508–509

- ^ Yinanç, Refet (1989). Dulkadir Beyliği (in Turkish). Ankara: Turkish Historical Society Press. ISBN 9751601711. OCLC 21676736.

- ^ Cecil H. Clough, The Duchy of Urbino in the Renaissance (Variorum Reprints, 1981) p.136

- ^ "Leonardo da Vinci: The Master's Master". The Eclectic Light Company. 2019-03-20. Retrieved 2022-08-26.

- ^ "York Minster FAQs". Archived from the original on 2007-11-16. Retrieved 2007-11-04.

- ^ J. R. Lander, Government and Community: England, 1450-1509 (Harvard University Press, 1980) p.284

- ^ Statutes at Large: From Magna Carta to 1800 (Great Britain, 1762)

- ^ Bell, Eric. "Taxus baccata: The English Yew Tree" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2019-04-04.

- ^ Ferran Soldevila, Història de Catalunya, p.772

- ^ Syed, Muzaffar Husain; Akhtar, Syed Saud; Usmani, B. D. (2011). Concise History of Islam. New Delhi: Vij Books. p. 150. ISBN 978-9381411094.

- ^ Tylenda, Joseph N. (1998). The Imitation of Christ. Vintage Spiritual Classics. p. xxvii. ISBN 978-0-375-70018-7.

- ^ Creasy, William C. (2007). The Imitation of Christ by Thomas a Kempis: A New Reading of the 1441 Latin Autograph Manuscript. Mercer University Press. p. xi. ISBN 9780881460971.

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). 1911. p. 74.

- ^ Šandera, Martin (2016). Jindřich starší z Minsterberka : syn husitského krále : velký hráč s nízkými kartami [Jindřich the Elder of Münsterberg: Son of the Hussite King: A Great Low-Card Player]. Prague: Vyšehrad. pp. 73–84. ISBN 978-80-7429-687-1.

- ^ De Girolami Cheney, Liana (2013). "Caterina Cornaro, Queen of Cyprus". In Barrett-Graves, Debra (ed.). The Emblematic Queen Extra-Literary Representations of Early Modern Queenship. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Fileti, Felice (2009). I Lusignan di Cipro (in Italian). Florence: Atheneum. p. 41.

- ^ Selcuk Aksin Somel (23 March 2010). The A to Z of the Ottoman Empire. Scarecrow Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-4617-3176-4.

- ^ "Die Tomburg bei Rheinbach", by Dietmar Pertz, in Rheinische Kunststätten, Issue 504, Cologne, 2008, ISBN 978-3-86526-026-0

- ^ Ross, James (2011). John de Vere, Thirteenth Earl of Oxford (1442-1513), 'The Foremost Man of the Kingdom'. Woodbridge, Suffolk: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-614-8.

- ^ Émile Toutey, ''Charles le Téméraire et la ligue de Constance (Charles the Bold and the League of Constance) (Paris: Hachette, 1902) pp. 49-51

- ^ a b Émile Toutey, ''Charles le Téméraire et la ligue de Constance (Charles the Bold and the League of Constance) (Paris: Hachette, 1902) pp. 58-59

- ^ Gabrielle Claerr-Stamm, Pierre de Hagenbach. Le destin tragique d'un chevalier sundgauvien au service de Charles le Téméraire (Pierre de Hagenbach: The tragic destiny of a Sundgauvian knight in the service of Charles the Bold) (Altkirch: Sundgau History Society, 2004) pp. 135-137

- ^ a b "Bătălia de la Vodnău (Vodna) (18-20 noiembrie 1473)" [The Battle of Vodnău, 18-20 November 1473]. crispedia.ro (in Romanian). Retrieved 4 August 2019.

- ^ Metlinger, Bartholomäus. "Ein Regiment der jungen Kinder". Europeana. Retrieved 2014-09-25.

- ^ Carter, F. W. (2006). Trade and Urban Development in Poland: An Economic Geography of Cracow, from Its Origins to 1795. Cambridge University Press. p. 364. ISBN 9780521024389.

- ^ Lubkin, Gregory (1994). A Renaissance Court: Milan Under Galleazzo Maria Sforza. University of California Press. p. 18.

- ^ Bunyitay Vincze (1883–1884). A váradi püspökség története [History of the Episcopate of Várad] (in Hungarian). Nagyvárad, Hungary: Episcopate of Várad. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ^ Charles D. Stanton, Medieval Maritime Warfare (Pen & Sword Maritime, 2015) ISBN 978-1-78159/251-9

- ^ Ladas, Stephen Pericles (1975). Patents, Trademarks, and Related Rights: National and International Protection, Volume 1. Harvard University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-674-65775-5.

- ^ Schippel, Helmut (2001). "Die Anfänge des Erfinderschutzes in Venedig". In Lindgren, Uta (ed.). Europäische Technik im Mittelalter, 800 bis 1400: Tradition und Innovation (4. ed.). Berlin: Wolfgang Pfaller. pp. 539–550. ISBN 3-7861-1748-9.

- ^ József Köblös; Szilárd Süttő; Katalin Szende (2000). "1474. Lengyel-magyar békekötés (Ófalui béke)" [1474. Polish-Hungarian peace conclusion (peace of Ófalu)]. Magyar Békeszerződések 1000–1526 [Hungarian peace treaties 1000–1526] (in Hungarian). Pápa, Hungary: Jókai Mór Városi Könyvtár. pp. 198–206. ISBN 963-00-3094-2.

- ^ Lander, J. R. (1981). Government and Community: England, 1450–1509. Harvard University Press. p. 287. ISBN 978-0-674-35794-5.

- ^ Williams, Hywel (2005). Cassell's Chronology of World History. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 185–187. ISBN 0-304-35730-8.

- ^ Vasiliev, Alexander A. (1936). The Goths in the Crimea. Cambridge, MA: Medieval Academy of America. p. 259.

- ^ Mendel, Menachem (2007). "The Earliest Printed Book in Hebrew". Archived from the original on August 27, 2021. Retrieved 2011-12-09.

- ^ "Book of Nature". World Digital Library. 2013-08-07. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ^ Anne Curry; Adrian R. Bell (September 2011). Soldiers, Weapons and Armies in the Fifteenth Century. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-84383-668-1.

- ^ "বাংলাদেশের কয়েকটি প্রাচীন মসজিদ". Inqilab Enterprise & Publications Ltd. 25 August 2015. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich Prokhorov (1973). Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Macmillan. p. 226.

- ^ Sten Lindroth (1976). A History of Uppsala University 1477-1977. Almqvist & Wiksell international. p. 6. ISBN 978-91-506-0081-0.

- ^ Heimann, Heinz-Dieter (2001). Die Habsburger: Dynastie und Kaiserreiche. C.H.Beck. pp. 38–45. ISBN 3-406-44754-6.

- ^ Penguin Pocket On This Day. Penguin Reference Library. 2006. ISBN 0-14-102715-0.

- ^ "Pazzi conspiracy | Italian history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Setton, Kenneth M. (1978). The Papacy and the Levant (1204–1571), Volume II: The Fifteenth Century. Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society. p. 328. ISBN 0-87169-127-2.

- ^ Brown, Alison (1979). Bartolomeo Scala, 1430-1497, Chancellor of Florence : the humanist as bureaucrat. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4008-6753-0. OCLC 767801631.

- ^ "Meditations, or the Contemplations of the Most Devout". World Digital Library. 1479. Retrieved 2013-09-04.

- ^ Pietro Bembo (2007). History of Venice: Books I-IV. Harvard University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-674-02283-6.

- ^ "Charles VIII | king of France". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Anne Crawford (February 22, 2007). The Yorkists: The History of a Dynasty. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 119. ISBN 978-0-8264-0989-8.

- ^ Albrecht Dürer; Peter Russell (24 May 2016). Delphi Complete Works of Albrecht Dürer (Illustrated). Delphi Classics. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-78656-498-6.

- ^ Russell LeRoi Bohr (1958). The Italian Drawings in the E.B. Crocker Art Gallery Collection, Sacramento, California. University of California, Berkeley. p. 35.

- ^ "Bianca Maria Sforza, regina dei Romani e imperatrice" (in Italian). Treccani. Retrieved 2022-08-26.

- ^ a b Sir James Henry Ramsay (1892). Lancaster and York: A Century of English History (A.D. 1399-1485). Clarendon Press. p. 469.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (1984). The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-87099-370-1.

- ^ "Copernicus born". History.com. A&E Television Networks. 9 February 2010. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Lynch, Michael, ed. (February 24, 2011). The Oxford Companion to Scottish history. Oxford University Press. p. 352. ISBN 9780199693054.

- ^ Krefeld Immigrants and Their Descendants. Vol. 13–17. Links Genealogy Publications. 1996. p. 59.

- ^ Grzonka, Michael (7 November 2016). Luther and His Times. Lulu Press, Inc. p. 58. ISBN 9781365515897.

- ^ Arlene Okerlund (2005). Elizabeth Wydeville: The Slandered Queen. Tempus. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-7524-3384-4.

- ^ Giraldi, Lilio Gregorio (31 May 2011). Grant, John N (ed.). Modern Poets. Harvard University Press. p. 336. ISBN 9780674055759.

- ^ Peter G. Bietenholz; Thomas Brian Deutscher (1 January 2003). Contemporaries of Erasmus: A Biographical Register of the Renaissance and Reformation. University of Toronto Press. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-8020-8577-1.

- ^ Plinio Prioreschi (1996). A History of Medicine: Renaissance medicine. Horatius Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-888456-06-6.

- ^ Barbara A. Somervill (February 2008). Michelangelo: Sculptor and Painter. Capstone. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-7565-1060-2.

- ^ "Stokesley, John (1475–1539), bishop of London". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/26563. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 26 October 2021. (Subscription, Wikipedia Library access or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Levin, Carole; Bertolet, Anna Riehl; Carney, Jo Eldridge (3 November 2016). A Biographical Encyclopedia of Early Modern Englishwomen: Exemplary Lives and Memorable Acts, 1500-1650. Taylor & Francis. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-315-44071-2.

- ^ "Leo X | pope". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Faris, David (1996). Plantagenet ancestry of seventeenth-century colonists: the descent from the later Plantagenet kings of England, Henry III, Edward I, Edward II, and Edward III, of emigrants from England and Wales to the North American colonies before 1701. Genealogical Pub Co. p. 324. ISBN 9780806315188.

- ^ Cohn-Sherbok, Lavinia (2 September 2003). Who's Who in Christianity. Routledge. p. 235. ISBN 9781134509560.

- ^ The Lambeth Review: A Quarterly Magazine of Theology, Christian Politics, Literature, and Art. Vol. 1. London: R. J. Mitchell and Sons. March 1872.

- ^ Brinton, Selwyn (1909). The Renaissance in Italian Art: A Series in Nine Parts. Vol. 5. G. Bell & Sons. p. 16.

- ^ "Louise Of Savoy | French regent". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- ^ Kathleen Wellman (21 May 2013). Queens and Mistresses of Renaissance France. Yale University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-300-19065-6.

- ^ Essential History of Art. Dempsey Parr. 2000. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-84084-952-3.

- ^ "History - Historic Figures: Thomas More (1478 - 1535)". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ "Clement VII | pope". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Panton, James (February 24, 2011). Historical Dictionary of the British Monarchy. Scarecrow Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-8108-7497-8.

- ^ The Encyclopedia Americana: The International Reference Work. Americana Corporation of Canada. 1962. p. 323.

- ^ The Genealogist. Association for the Promotion of Scholarship in Genealogy. 1982. p. 38.

- ^ Jean Clare-Tighe (13 June 2017). Loyaulté Me Lie: Loyalty Binds Me. Troubador Publishing Ltd. p. 20. ISBN 978-1-78803-348-0.

- ^ Debrett's Peerage and Baronetage. Debrett's Peerage Limited. 2011. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-870520-73-7.

- ^ David Hipshon (2011). Richard III. Routledge. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-415-46281-5.

- ^ Geoff Brown (15 December 2008). The Ends of Kings. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-4456-3143-1.

- ^ "Paul II | pope". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- ^ Solitudo: Spaces and Places of Solitude in Late Medieval and Early Modern Cultures. BRILL. 1 June 2018. p. 393. ISBN 978-90-04-36743-2.

- ^ The Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage & Companionage of the British Empire. 1907. p. 103.

- ^ E. B. Pryde; D. E. Greenway; S. Porter; I. Roy (23 February 1996). Handbook of British Chronology. Cambridge University Press. p. 482. ISBN 978-0-521-56350-5.

- ^ Exeter Diocesan Architectural and Archaeological Society (1867). Transactions of the Exeter Diocesan Architectural Society. Exeter, England: EDAAS. p. 218.

- ^ Reinhard Strohm (17 February 2005). The Rise of European Music, 1380–1500. Cambridge University Press. p. 285. ISBN 978-0-521-61934-9.

- ^ The New Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 2003. p. 733. ISBN 978-0-85229-961-6.

- ^ Ogg, Oscar (1952). A New Survey of Universal Knowledge. Crowell. p. 313. ISBN 9780690841152.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Thelma Anna Leese (1996). Blood Royal: Issue of the Kings and Queens of Medieval England, 1066-1399: the Normans and Plantagenets. Heritage Books. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-7884-0525-9.

- ^ Radu Florescu; Raymond T. McNally (1973). Dracula: A Biography of Vlad the Impaler, 1431-1476. Hawthorn Books. p. 115.

- ^ Guild of the Holy Cross (Stratford-upon-Avon, England) (2007). The Register of the Guild of the Holy Cross, St Mary and St John the Baptist, Stratford-upon-Avon. Dugdale Society. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-85220-088-9.

- ^ a b c Lauro Martines (24 April 2003). April Blood: Florence and the Plot against the Medici. Oxford University Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-19-988239-7.

- ^ N. W. James; V. A. James (2004). The Bede Roll of the Fraternity of St. Nicholas: The Bede roll. London Record Society. p. 58.

- ^ Dr Bart Lambert; Dr Katherine Anne Wilson (28 January 2016). Europe's Rich Fabric: The Consumption, Commercialisation, and Production of Luxury Textiles in Italy, the Low Countries and Neighbouring Territories (Fourteenth-Sixteenth Centuries). Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4724-0610-1.