Zhong Kui

| Zhong Kui | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

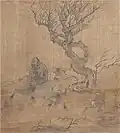

A Ming painting of Zhong Kui the Demon Queller with Five Bats, with the five bats representing the five blessings as well as the vase, red coral, and fungi—held by demons—that also contain auspicious symbolism | |||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 鍾馗 | ||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 钟馗 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Chung Quỳ | ||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 鍾馗 | ||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 종규 | ||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 鍾馗 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 鍾馗 | ||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Zhong Kui (Chinese: 鍾馗; pinyin: Zhōng Kuí) is a Taoist deity in Chinese mythology, traditionally regarded as a vanquisher of ghosts and evil beings. He is depicted as a large man with a big black beard, bulging eyes, and a wrathful expression. Zhong Kui is able to command 80,000 demons to do his bidding and is often associated with the five bats of fortune. Worship and iconography of Zhong Kui later spread to other East Asian countries.

In art, Zhong Kui is a frequent subject in paintings and crafts, and his image is often painted on household gates as a guardian spirit as well as in places of business where high-value goods are involved. He is also commonly portrayed in popular media.

King of ghosts

According to folklore, Zhong Kui travelled with Du Ping (杜平), a friend from his hometown, to take part in the state-wide imperial examinations held in the capital city Chang'an. Though Zhong Kui attained great academic success through his achievement of top honors in the major exams, his rightful title of "Zhuangyuan" (top-scorer) was stripped from him by the then emperor because of his disfigured and ugly appearance.[1]

Extremely enraged, Zhong Kui died by suicide by continually hurling himself against the palace gates until his head was broken, whereupon Du Ping had him buried and laid to rest. During the divine judgment after his death from suicide, Yanluo Wang (the Chinese Underworld Judge) saw much potential in Zhong Kui, intelligent and smart enough to score top honors in the imperial examinations but condemned to Youdu because of the strong grievance. Yanluo Wang then gave him a title as the king of ghosts and tasked him to hunt, capture, take charge of and maintain discipline and order among all ghosts.

After Zhong Kui became the king of ghosts in Hell, Zhong Kui returned to his hometown on Chinese New Year's eve. To repay Du Ping's kindness, Zhong Kui gave his younger sister in marriage to Du Ping.[2]

Capturing ghosts

Sources

The earliest extant reference to Zhong Kui appears in the Supplementary Notes to Dream Pool Essays by the Northern Song scholar Shen Kuo, which mentions a Zhong Kui portrait then attributed to the Tang painter Wu Daozi together with its inscription.[3] By the Ming anthology Tianzhongji (Chinese: 天中記, Records from Mount Tianzhong), quoting Tang Yishi (Chinese: 唐逸史), the story of Zhong Kui catching ghosts had taken on its standard form.[4]

Tang dynasty customs attested in practice

From the High Tang onward, it became customary for the emperor to bestow Zhong Kui portraits on ministers at year's end, and several sources record the practice:

- Zhang Yue's Memorial of Thanks for the Bestowal of a Zhong Kui Portrait and Calendar (Chinese: 謝賜鍾馗及曆日表), describes how the imperial gift of a Zhong Kui painting and a new almanac was woven into New-Year celebrations during Emperor Xuanzong's reign.[5]

- Liu Yuxi submitted two analogous memorials in Emperor Dezong's reign: Memorial, on Behalf of Vice-Minister Li, Thanking for a Zhong Kui Portrait and New Calendar (Chinese: 為李中丞謝鍾馗曆日表) and Memorial, on Behalf of Chancellor Du, Thanking for a Zhong Kui Portrait and New Calendar (Chinese: 為淮南杜相公謝鍾馗曆日表). Both record that the court distributed Zhong Kui paintings, so officials could ward off evil at year's end.[6][7]

- New-Year's Eve Invocation to Zhong Kui for Performing Nuo to Expel Evil (Chinese: 除夕鍾馗驅儺文) recorded in Dunhuang manuscript, shows Zhong Kui acting as the evil-repelling protagonist in New-Year Nuo rites.[8]

Taken together, these accounts indicate that by the time of Emperor Xuanzong, Zhong Kui's evil-quelling image was already widespread in both court ritual and popular custom.[9]

Later reinforcement of Zhong Kui's image

In literary works such as Zhong Kui: The Complete Chronicles (Chinese: 鍾馗全傳), The Tale of Quelling Ghosts (Chinese: 平鬼傳) and The Tale of Slaying Ghosts (Chinese: 斬鬼傳), Zhong Kui is further portrayed as an incorruptible champion of justice who rids the world of evil on behalf of the people, and is held in deep popular esteem.[10]

In summary, Zhong Kui's true origin remains unresolved; his figure and worship are the cumulative result of folk practice, religious ritual, and literary-artistic creation across a long sweep of history.

Tales and cultural reference

In the Supplementary Notes to Dream Pool Essays, Shen Kuo records seeing a painting, then attributed to Wu Daozi (Chinese: 吳道子), the renowned Tang painter, together with an inscription recounting a dream of Emperor Xuanzong. According to the inscription, during the Kaiyuan reign, Emperor Xuanzong (Chinese: 唐玄宗, also known as Tang Minghuang) returned to the palace after supervising military exercises on Mount Li, fell ill, and remained unwell for more than a month. One night, he dreamed of two ghosts: a small red-trousered spirit—shod on one foot, the other shoe hanging at its belt, bamboo fan in hand—who snatched Consort Yang's (Chinese: 楊貴妃, Yang Guifei; Taoist name Taizhen) purple sachet and the emperor's jade flute and raced about the hall, and a larger, fearsome figure in a battered cap and blue robe, one sleeve stripped and both legs bound in hide, who seized the thief, gouged out its eyes and swallowed them. The emperor asked the larger ghost his name. He replied, "My humble name is Zhong Kui—once a failed candidate in the imperial military examination". Waking up, Xuanzong thereupon ordered the court painter Wu Daozi to depict the dream exactly as he had seen it. Wu completed the commission, and when the painting was presented, the emperor marvelled that the image corresponded to his vision in every detail.[11]

In the Ming anthology Tianzhongji (Chinese: 天中記, Records from Mount Tianzhong), which cites Tang Yishi (Chinese: 唐逸史, Unofficial History of the Tang Dynasty), the Zhong Kui narrative assumes its canonical form. After returning from Mount Li, Emperor Xuanzong fell ill and remained bedridden for over a month. In the midst of fever, he dreamed of a small ghost that called itself Xuhao (Chinese: 虛耗, Xūhào, meaning "wasteful expenditure" and "consuming blessings for nothing"), which stole Consort Yang's sachet and the emperor's flute. At that moment, a far larger spectre burst in—hair dishevelled, beard bristling, visage stern, clad in a blue robe—seized the small ghost, gouged out its eyes and devoured them. To the startled emperor the large ghost announced that he was Zhong Kui of Mount Zhongnan, a failed candidate in the imperial military examination during Gaozu's Wude reign (Chinese: 高祖武德年間, Emperor Gaozu of Tang's reign) who, shamed by his defeat, had dashed his head against the palace steps and died. Grateful for Gaozu's gift of a green robe (the attire of lower-ranking officials, a token of imperial recognition) and honourable burial, he had sworn to rid Great Tang of every Xuhao ghost. Xuanzong awoke drenched in sweat, and his malarial fever was miraculously cured. Emperor Xuanzong thereupon summoned the court painter Wu Daozi and commanded him to set down the dream exactly as it had appeared. Wu's brush produced a likeness so vivid it seemed wrought from firsthand sight, astonishing the emperor.[12]

In the generations that followed, Wu Daozi's archetype spawned an entire genre of Zhong Kui imagery. Alongside Zhong Kui Capturing the Ghost, painters produced Zhong Kui Slaying Ghosts (Chinese: 鍾馗斬妖圖), Zhong Kui Setting Out (Chinese: 鍾馗出行圖) and Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (Chinese: 鍾馗嫁妹圖), all intended to dispel evil and avert calamity. The "marrying-off" scene most likely capitalises on the near-homophones "嫁妹" (pronounced as: jià mèi, meaning "marry off a younger sister") and "嫁魅" (pronounced as: jià mèi, meaning "send a evil spirit away"), reflecting popular ambivalence towards ghosts: fear of their mischief, yet a wish to placate them through ritual courtesy[13][14]. In the painting, ghost-servants hoist banners and parasols, sound horns and bear a bridal palanquin, lending a celebratory air to a subject otherwise devoted to evil-banishing. For this reason, the painting stands apart from sterner counterparts (such as Driving Away Evil in Dragon Boat Festival (Chinese: 天中驅邪圖), Zhongkui Catching Ghosts (Chinese: 鍾馗捉鬼), and Shenshuand Yulü (Chinese: 神荼鬱壘).

Popularization in later dynasties

Zhong Kui's popularity in folklore can be traced to the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang China (712 to 756). According to Song dynasty sources, once the Emperor Xuanzong was gravely ill and had a dream in which he saw two ghosts. The smaller of the ghosts stole a purse from imperial consort Yang Guifei and a flute belonging to the emperor. The larger ghost, wearing the hat of an official, captured the smaller ghost, tore out his eye and ate it; then, he introduced himself as Zhong Kui. He said that he had sworn to rid the empire of evil. When the emperor awoke, he had recovered from his illness. So he commissioned the court painter Wu Daozi to produce an image of Zhong Kui to show to the officials. This was highly influential to later representations of Zhong Kui.[15][16]

Iconography and worship

In ancient depictions, Zhong Kui is usually depicted in a blue robe and a battered cap, summed up by the terse line "Cap ragged, robe blue, horned belt at the waist". [17][18]

Today, the prevailing image shows him in vermilion court robe and a black gauze cap, sometimes carrying a sword at his side, at other times holding a folding fan, while he stands upon a subdued ghost. Five diminutive ghost-servants surround him, each bearing a specific object— a lantern, a seal, a parasol, a horse-lead and a gourd—an image known by the folks as "five-ghost portage", thought either to ferry wealth or to symbolise five ghostly aides able to subdue the Five Plague Gods. A bat usually hovers beside Zhong Kui: it scouts for evil spirits and, because in Chinese "蝠" (fú, bat) homophones with "福" (fú, fortune), also conveys a wish for blessing.[19]

In the Tang dynasty, Zhong Kui worship first took shape, and its earliest complete record links him to Emperor Xuanzong. Tradition relates that Xuanzong once dreamed of Zhong Kui chasing away a malignant spirit from the palace; on waking, he ordered the court painter to set down the figure so that it might guard the precincts and rout evil, thereby securing Zhong Kui's title of "Ghost-Repelling Deity".[20] Tang scholar-officials such as Zhang Yue[21] and Liu Yuxi [22]record receiving Zhong Kui portraits as seasonal gifts. The Dunhuang manuscripts likewise preserve ritual texts, among them New-Year's Eve Invocation to Zhong Kui for Performing Nuo to Expel Evil, which shows that his image had already assumed an important place in state ceremony. In the Song and Yuan periods, Daoism placed Zhong Kui on the divine register, honouring him as "Sage Lord Who Bestows Fortune and Guards the Household" (Chinese: 賜福鎮宅聖君) and charging him with protecting dwellings, banishing evil and ushering in good fortune.

Among common folks, his worship deepened as well: at Chinese New Year, house-warmings, shop openings and temple fairs, people would hang his portrait or perform the rite of "Zhong Kui Dance" (Chinese: 跳鍾馗) to drive away evil and secure peace. In this rite, a performer portraying Zhong Kui dons vermilion court robe and a mask, brandishes a sword or holds a symbolic bat, and enacts the banishment of calamity together with the bestowal of blessings.[23]

In addition, the Ming-period medical classic Bencao Gangmu (Chinese: 本草綱目, Compendium of Materia Medica) records that portraits of Zhong Kui were burnt to ash and combined with other herbs to make pills used against obstructed labour[24], malaria and similar ailments, showing that his worship extended even into folk medicine.[25].

In the present day, Zhong Kui worship remains active across many regions of China, flourishing above all in Zhouzhi, Shaanxi (held to be his native county), throughout the Jiang–Huai region, in southern Fujian (Minnan) and in Taiwan. Devotees employ images, rites and dramatic performance to intensify his twin symbols of evil-banishing and fortune-bringing.[26]

Legacy

Zhong Kui and his legend became a popular theme in later Chinese painting, art, and folklore. Pictures of Zhong Kui used to be frequently hung up in households to scare away ghosts. His character was and still is especially popular in New Year pictures.[16]

Moreover, the popularity of Zhong Kui gives rise to the idiom "Da Gui Jie Zhong Kui" (打鬼借鍾馗), which could be translated as "Borrow the name of Zhong Kui to smash the ghost", which means to finish a task by masquerading it is done for someone greater in power or status. Some argue that Mao Zedong is the first to use this phrase.[27]

In art

Twentieth-century painter Quan Xianguang (b. 1932) painted Zhong Kui as a burly, hairy man holding a sturdy sword in his bared right arm.[28]

-

Dai Jin's The Night Excursion of Zhong Kui (15th century), depicting Zhong Kui undertaking a night patrol while being carried in a sedan chair by four demons

Dai Jin's The Night Excursion of Zhong Kui (15th century), depicting Zhong Kui undertaking a night patrol while being carried in a sedan chair by four demons -

Wen Zhengming's Zhong Kui in a Wintry Grove (Ming dynasty), matching Ge Hong's Master Embracing Simplicity that states that ominous creatures often haunted forests, which is why Zhong Kui is needed there

Wen Zhengming's Zhong Kui in a Wintry Grove (Ming dynasty), matching Ge Hong's Master Embracing Simplicity that states that ominous creatures often haunted forests, which is why Zhong Kui is needed there -

Zhong Kui and Spiders by Zhou Xun (1649–1729), depicting Zhong Kui eyeing spiders dangling down from above (a rebus or auspicious pun for 'joyful things')

Zhong Kui and Spiders by Zhou Xun (1649–1729), depicting Zhong Kui eyeing spiders dangling down from above (a rebus or auspicious pun for 'joyful things') -

Ren Yi's Zhong Kui (1883), in which Zhong Kui appears as an elegant but somewhat eccentric scholar, with his sword sheathed and a blossom in his hair, as he decorously reads

Ren Yi's Zhong Kui (1883), in which Zhong Kui appears as an elegant but somewhat eccentric scholar, with his sword sheathed and a blossom in his hair, as he decorously reads -

Auspicious Omen of Abundant Peace (Qing dynasty), humorously depicting Zhong Kui being shocked as he looks at his grotesque visage in the mirror

Auspicious Omen of Abundant Peace (Qing dynasty), humorously depicting Zhong Kui being shocked as he looks at his grotesque visage in the mirror -

Zhong Kui is seen waving his sword at five bats representing the five blessings, as if symbolically bringing these fortunes down to someone as recipient, depicted in a late 19th or early 20th century xylograph

Zhong Kui is seen waving his sword at five bats representing the five blessings, as if symbolically bringing these fortunes down to someone as recipient, depicted in a late 19th or early 20th century xylograph -

Zhong Kui, the Demon Queller (17th century), in which Zhong Kui rides an ox while quelled demons carry his sword or lead his ox

Zhong Kui, the Demon Queller (17th century), in which Zhong Kui rides an ox while quelled demons carry his sword or lead his ox -

A 16th-century painting, depicting a seated Zhong Kui

A 16th-century painting, depicting a seated Zhong Kui -

A 17th-century painting by Lu Xue, depicting Zhong Kui with demons

A 17th-century painting by Lu Xue, depicting Zhong Kui with demons -

A painting by the Shunzhi Emperor (r. 1643–1661) of the Qing dynasty

A painting by the Shunzhi Emperor (r. 1643–1661) of the Qing dynasty -

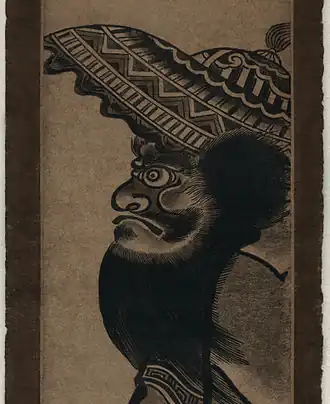

A detail of Okumura Masanobu's Shōki zu (Shōki striding), dated c. 1741–1751.

A detail of Okumura Masanobu's Shōki zu (Shōki striding), dated c. 1741–1751. -

Fei Danxu's Zhong Kui and his Assistants Under Willows (1832), depicting Zhong Kui and his demon helpers

Fei Danxu's Zhong Kui and his Assistants Under Willows (1832), depicting Zhong Kui and his demon helpers -

Zhong Kui by Min Zhen (1730–after 1791), depicting Zhong Kui riding a quadrupedal creature

Zhong Kui by Min Zhen (1730–after 1791), depicting Zhong Kui riding a quadrupedal creature -

A 1776 painting by Min Zhen, in which Zhong Kui sits and leans on a chair

A 1776 painting by Min Zhen, in which Zhong Kui sits and leans on a chair -

Zhong Kui and Demons Crossing a Bridge (16th century), depicting Zhong Kui on a donkey

Zhong Kui and Demons Crossing a Bridge (16th century), depicting Zhong Kui on a donkey -

Zhong Kui Appreciating Plum Blossom (18th century)

Zhong Kui Appreciating Plum Blossom (18th century) -

Copper tsuba depicting Shōki, by Masayuki Tsuba (1695–1769)

Copper tsuba depicting Shōki, by Masayuki Tsuba (1695–1769)

Temples

- Zhong Kui Temple (钟馗庙) in Guanqiao, Hunan

- Shuiwei Zhengwei Temple (水尾震威宮) in Xizhou, Changhua

- Guang Lu Temple (光祿廟) in Zhuqi, Chiayi

- Wu Fu Temple (五福宮) in Wanhua, Taipei

- Zhong Nan Old Temple (終南古廟), Batu Pahat, Johor

- Shōki Shrine (鍾馗神社) in Higashiyama Ward, Kyoto

In popular culture

The Dance of Zhong Kui (跳鍾馗) developed under the Song dynasty and was adapted into opera under the Ming. It is also a form of ritual for exorcism and purification purpose. this tradition still survives today across China, both in the north especially the Huyi District of Shaanxi and in the south especially She County of Anhui, and Taiwan.[29]

Zhong Kui was a minor deity in the 2015 expansion "Tale of the Dragon" of the videogame Age of Mythology.[30] Not available in Age of Mythology: Retold.

Zhong Kui was released as a deity in the video game Smite in 2013.[31]

In 2025, Game Science announced Black Myth: Zhong Kui, a videogame based on Zhong Kui as main character.[32]

See also

- Cheng Huang Gong, Chinese City God

- Chinese numismatic charm

- Fulu

- Hei Bai Wu Chang, Chinese constables of underworld

- Imperial examination in Chinese mythology

- Kui in Chinese mythology

- Menshen, Chinese Door Gods

- The Five Poisons

- Yanluo Wang, Chinese Underworld Judge

References

- ^ 刘, 锡诚. [刘锡诚]钟馗传说和信仰的滥觞 · 中国民俗学网-中国民俗学会 · 主办 ·. www.chinafolklore.org. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Nagendra Kumar Singh (1997). International encyclopaedia of Buddhism: India [11]. Anmol Publications. pp. 1372–1374. ISBN 978-81-7488-156-4. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ 沈括. 《梦溪笔谈/补笔谈·卷三·杂志》.

- ^ 陈耀文. 《天中記 (四庫全書本)/卷04·梦钟馗》.

- ^ 张说. 《謝賜鍾馗及曆日表》.

- ^ 刘禹锡. 《為李中丞謝賜鍾馗曆日表》.

- ^ 刘禹锡. 《為淮南杜相公謝賜鍾馗曆日表》.

- ^ 张兵;张毓洲 (2008-02-15). "从敦煌写本《除夕钟馗驱傩文》看钟馗故事的发展和演变". 敦煌研究 (2008年第1期): 102-105. ISSN 1000-4106 – via 敦煌学信息资源库.

- ^ 吳加敏; 舒芷玲; 顏淑麗 (2011). "《鍾馗民俗信仰與其神話文學形象》". 神話與文學論文選輯 2010-2011: 74-92. Retrieved 2025-08-21 – via Digital Commons @ Lingnan University.

宮中對鍾馗的信仰是極為重視的,所以在民間人們對鍾馗的信仰亦不可忽視。

- ^ 劉笑芬; 鍾文珊 (2009). "鍾馗神話及文學分析". 《神話與文學論文選輯 2008-2009》: 162-202. Retrieved 2025-08-21 – via Digital Commons @ Lingnan University.

- ^ 沈括. 《梦溪笔谈/补笔谈·卷三·杂志》.

- ^ 陈耀文. 《天中記 (四庫全書本)/卷04·梦钟馗》.

- ^ 高凤玉 (December 2021). "《鍾馗嫁妹》裡的溫柔 鍾馗的神格與人格" (in Chinese). Retrieved 2025-08-21.

- ^ 姜乃菡 (2013). "《钟馗嫁妹故事的流变及其文化内涵》". 民族文學研究 (5): 162-168.

笔记中主要是对钟馗及钟馗嫁妹故事的溯源,如清俞樾《茶香室三钞》卷二十通过明文震亨《长物志》描述的十二月挂钟馗的目的,推断出钟馗嫁妹为嫁魅之讹,这便是嫁妹故事起源的一种解释。

- ^ Richard Von Glahn (2004). The Sinister Way: The Divine and the Demonic in Chinese Religious Culture. University of California Press. pp. 122–128. ISBN 978-0-520-92877-0. Retrieved 7 June 2013.

- ^ a b Dillon, Michael, ed. (1998). China: A Cultural and Historical Dictionary. London: Curzon Press. pp. 382. ISBN 0-7007-0439-6.

- ^ 《事物紀原》

- ^ 《唐逸史》

- ^ 科普在線.端午鍾馗降福錢 Archived 2014-06-05 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 沈括. 《夢溪筆談/補筆談•卷三•雜志》.

靈祗應夢,厥疾全瘳。烈士除妖,實須稱獎。因圖異狀,頒顯有司。歲暮驅除,可宜遍識,以祛邪魅,兼靜妖氛。詔告天下,悉令知委。

- ^ 张说. 《謝賜鍾馗及曆日表》.

- ^ 刘禹锡. 《為李中丞謝賜鍾馗曆日表》.

- ^ "〈跳钟馗〉". 台湾宗教文化资产 (in Traditional Chinese). Archived from the original on 2025-08-15. Retrieved 2013-12-25.

- ^ 李时珍:《本草綱目 (四庫全書本)/全览3·鍾馗綱目》

- ^ 江, 淑惠 (January 2025). "台灣鍾馗信仰之研究:以清朝興建之廟宇為考察對象". 東亞漢學研究 (特別號). 長崎: 東亞漢學研究學會: 206–219. ISSN 2185-999X.

在中國傳統的醫學中,這種民間的療法也曾經具有正統的地位。很多長期臥病的人,或是生了不知名的奇異特症,最後常因為此法而得以康復

- ^ 江, 淑惠 (January 2025). "台灣鍾馗信仰之研究:以清朝興建之廟宇為考察對象". 東亞漢學研究 (特別號). 長崎: 東亞漢學研究學會: 206–219. ISSN 2185-999X.

- ^ 吴, 志菲. 毛泽东对"个人崇拜"的态度演变【3】--党史频道-人民网. dangshi.people.com.cn. Retrieved 11 February 2023.

- ^ Shelagh Vainker and Xin Chen, editors, A Life in Chinese Art: Essays in Honor of Michael Sullivan, p. 83.

- ^ Zheng, Zunren (2004). Zhong Kui yan jiu (BOD 1 ban ed.). Taibei Shi: Xiu wei zi xun ke ji gu fen you xian gong si. pp. 225–241. ISBN 9789867614285.

- ^ "Official Age of Mythology: Tale of the Dragon Preview Hub! - Age of Empires - World's Edge Studio". 2016-01-19. Retrieved 2025-08-21.

- ^ L, Nikola (2023-07-04). "SMITE God Release Dates Sorted Chronologically". Prima Games. Retrieved 2025-08-21.

- ^ Carpenter, Lincoln (19 August 2025). "Black Myth: Zhong Kui, the follow-up to Black Myth: Wukong, just got a surprise Gamescom reveal". PC Gamer.

External links

Media related to 鍾馗 at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 鍾馗 at Wikimedia Commons- ‘The Legend of Zhong Kui’: A Poem by M.D. Skeen, the Society of Classical Poets (June 5, 2025)