Hong Taechawanit

Hong Taechawanit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1851 |

| Died | 5 March 1937 (aged 85–86) Bangkok, Thailand |

| Occupation(s) | Businessman and philanthropist |

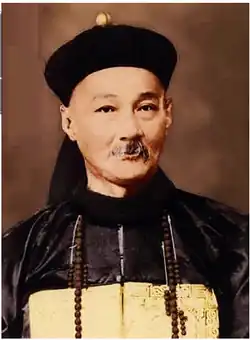

Hong Taechawanit (ฮง เตชะวณิช; RTGS: Techawanit[1]) born Zheng Yifeng[2] (1851–5 March 1937) and also known as Zheng Zhiyong[3] or Er Ge Feng[4] (lit. 'Second Brother Feng', rendered in Thai as Yi Ko Hong[5]), was a Chinese businessman, philanthropist, and secret society member active in early twentieth-century Siam.

He was later ennobled by King Vajiravudh (Rama VI) with the title Phra Anuwat Ratchaniyom (พระอนุวัฒน์ราชนิยม), and granted the surname Techawanit (originally romanized Tejavanija).[6][7]

Early life

Sources diverge on Hong’s origins. Thai accounts hold he was born in Bangkok in 1851, the son of Khia Tae, a Teochew immigrant, and Keut, a Thai woman. After his parents’ early deaths, he was raised by relatives in Guangdong Province, China, before returning to Siam at age sixteen (1866/1867).[8]

Chinese sources state he was born in Qiyuan Village, Chao’an County, Chaozhou, Guangdong. His father, Zheng Shisheng (鄭詩生), fled China during the First Opium War but died en route to Thailand. After his mother remarried, Yifeng moved to Thailand and settled in Bangkok.[9]

Career

While working for gambling magnate Liu Jibin (劉繼賓), Hong became a member of the clandestine Chinatown-based 'Tian Di Hui' (天地會) or 'Heaven and Earth Society'. He acquired the nickname Er Ge Feng ("Second Brother Feng") as the society's second-highest authority and became leader after his predecessor's death.[10]

Hong successfully petitioned King Chulalongkorn for tax farming rights over gambling houses. In 1909, he dissented from popular Chinese sentiment against tax reforms and refused to join a three-day strike.[11] In June 1918, he was granted the surname Taechawanit (Tejavanija),[12] and conferred the title of Phra Anuwat Ratchaniyom by King Vajiravudh.[13][14]

He built a conglomerate comprising pawnshops, a printing press, a shipping line,[15] a theatre,[16] and the biggest gambling house in the country.[17] His mansion in Phlapphla Chai served as his company headquarters.[18]

He financed schools in Thailand and China, newspapers, charities, and flood relief in Guangdong (380,000 silver dollars in 1918).[19]

Final years and legacy

Hong sympathised with the Kuomintang led by Sun Yat-sen, gifting Sun with ivory after the 1911 revolution. After losing his tax farming license, he died on 5 March 1937, aged 84.[20] Taechawanit Road, which he financed, is named after him.[21] His mansion became the present-day Phlapphachai Police Station.[22] Deified as a 'luck-bringer', he remains worshipped by Thai gamblers.[23][24]

References

- ^ Wasana Wongsurawat (2019). The Crown and the Capitalists: The Ethnic Chinese and the Founding of the Thai Nation. University of Washington Press. p. 53.

- ^ simplified Chinese: 郑义丰; traditional Chinese: 鄭義豐; pinyin: Zhèng Yìfēng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tēⁿ Gī Hong

- ^ simplified Chinese: 郑智勇; traditional Chinese: 鄭智勇; pinyin: Zhèng Zhìyǒng

- ^ simplified Chinese: 二哥丰; traditional Chinese: 二哥豐; pinyin: Èr Gē Fēng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Jī Ko Hong

- ^ ยี่กอฮง

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). Southeast Asian Personalities of Chinese Descent: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume I & II. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 352–353.

- ^ Murashima, Eiji (2013). "The Origins of Chinese Nationalism in Thailand." Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies, Waseda University. pp. 149–172.

- ^ ศาลเจ้าพ่อหวยคนแรกของไทย! บนโรงพักพลับพลาชัย Archived 2014-04-10 at the Wayback Machine www.go6tv.com

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). p. 352.

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). p. 352.

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). p. 352.

- ^ "นามสกุลพระราชทาน: อักษร ต" [Royally bestowed surnames: T]. Phya Thai Palace (in Thai). Retrieved 8 September 2022.

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). pp. 352–353.

- ^ Murashima, Eiji (2013). pp. 149–172.

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). p. 352.

- ^ Vella, Walter F. (2019). Chaiyo!: King Vajiravudh and the Development of Thai Nationalism. University of Hawaii Press. p. 201.

- ^ Wasana Wongsurawat (2019). p. 53.

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). p. 352.

- ^ Benton, Gregor & Liu, Hong (2020). "Qiaopi and Charity." In Fitzgerald, John & Hon-ming Yip (Eds.), Chinese Diaspora Charity and the Cantonese Pacific, 1850–1949. Hong Kong University Press. p. 62.

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). p. 353.

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). p. 352.

- ^ Goh, Yu Mei (2012). p. 353.

- ^ Pennick, Nigel (2021). The Ancestral Power of Amulets, Talismans, and Mascots: Folk Magic in Witchcraft and Religion. Simon and Schuster. p. 6.

- ^ Erker, Ezra Kyrill (28 April 2013). "A group that went forth and prospered around the world". The Bangkok Post.

Bibliography

- Benton, Gregor; Hong, Liu (2020). "Qiaopi and Charity". In John Fitzgerald; Hon-ming Yip (eds.). Chinese Diaspora Charity and the Cantonese Pacific, 1850–1949. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 51–71. ISBN 9789888528264.

- Goh, Yu Mei (2012). "Hong Taechawanit". In Leo Suryadinata (ed.). Southeast Asian Personalities of Chinese Descent: A Biographical Dictionary, Volume I & II. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 352–353. ISBN 9789814345217.

- Murashima, Eiji (2013). "The Origins of Chinese Nationalism in Thailand". Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies. Waseda University: 149–172.

- Pennick, Nigel (2021). The Ancestral Power of Amulets, Talismans, and Mascots: Folk Magic in Witchcraft and Religion. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781644112212.

- Vella, Walter F. (2019). Chaiyo!: King Vajiravudh and the Development of Thai Nationalism. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824880309.

- Wasana, Wongsurawat (2019). The Crown and the Capitalists: The Ethnic Chinese and the Founding of the Thai Nation. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295746265.