Zenga

Zenga (禅画; "zen picture") is a subset of Zen painting that encompasses the sumi-e painting and calligraphy of Japanese Zen Masters during the Edo period[1] and Meiji period[2]. It is characterized by direct, simple, and expressive brush work, usually in monochrome. Zenga paintings featured traditional Buddhist figures such as Daruma, Kanzan and Jittoko, and Hotei, often depicted in comical caricatures. Zen sayings, also brushed in rough calligraphy, accompanied the paintings. Simple motifs such as the Ensō, the Zen Masters staff or calligraphy without painting were also popular themes in Zenga.[3] See the Paintings Section for examples of Zen themes in Zenga artwork.

The term "Zenga" (the Japanese pronunciation of “Zen painting”) was introduced by Japanese-born Swiss scholar Kurt Brasch's books Hakuin and Zenga (1957) and Zenga (1962), as well as the traveling Zenga exhibition he organized in Europe from 1959 to 1960. These postwar Zenga exhibitions were particularly influential. [4] Brasch's use of the term "Zenga," however, prompted criticism from some Japanese scholars including Takeuchi Naoji, who argued that it narrowly categorized the art.[5]

Zenga is sometimes contrasted with "nanga," or "literati painting," made by scholars.[6]

Zenga Style

In many instances, both calligraphy and image will be in the same piece. The calligraphy denotes a poem, or saying, that teaches some element of the true path of Zen. These inscriptions are usually short, often written in kana.[7] The brush painting is characteristically simple, bold and abstract, and the style often playful and spontaneous.

Zenga in the Culture of the Tokugawa Shogunate

The Edo period saw a new popularization of Zen.[8] During the Edo period Zenga was not confined to the spiritual and educational discipline within the monastic Zen community but became one of several forms of Zen Buddhist outreach into the lay community. With the ushering in of the Tokugawa shogunate, “Religion came to penetrate the lives of the general populace, not just as a primitive faith, but also as a system of beliefs, that had undergone considerable intellectual refinement while sustained by the teachings and rituals of Buddhism and Shinto.[9]

Hakuin Ekaku

Hakuin Ekaku, (1685-1768) was a Zen Master of the Rinzai sect and abbot of the Shōin-ji temple in Hara, Japan. Hakuin is considered one of the foremost artists in the Zenga oeuvre.[10] He took up brush painting when in his 60's and produced thousands of works up to the end of his life.[11]

Sengai Gibon

Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) was another notable Zenga monk/artist. He was the abbot of the Shōfuku-ji temple in Hakata, Japan, retiring in 1811. Like Hakuin, most of his ink painting was done in the later years of his life. Sengai is known for his roughly-brushed, comical style of painting. [5]

See Also

References

- ^ Addiss, Stephen (1976). ´´Zenga and Nanga´´. New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art. p. 37.

- ^ Seo, Audrey Yoshiko; Addiss Stephen (2000). ´´The Art of Twentieth Century Zen´´. Boston: Shambhala Publications. p. 3.

- ^ Stevens, John (1990). ´´ZENGA Brushstrokes of Enlightenment´´. New Orleans: New Orleans Museum of Art.

- ^ Lippit, Yukio. "Zenga: A Brief History". Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ a b Aviman, Galit (5 July 2017). Zen Paintings in Edo Japan (1600-1868): Playfulness and Freedom in the Artwork of Hakuin Ekaku and Sengai Gibon. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781351536110. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Kobayashi, Tadashi; Rotondo-McCord, Lisa E. (2002). An Enduring Vision: 17th-20th-century Japanese Painting from the Gitter-Yelen Collection. New Orleans Museum of Art. ISBN 9780894940873. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Bruschke-Johnson, Lee (22 November 2021). Dismissed as Elegant Fossils: Konoe Nobutada and the Role of Aristocrats in Early Modern Japan. Brill. ISBN 9789004487604. Retrieved 8 March 2023.

- ^ Sawada, Janine Anderson (1993). Confucian Values and Popular Zen. Honolulu: University of Hawaii. pp. 23–26. ISBN 978-0-8248-1414-4.

- ^ Bitō, Masahide (1991). "Thought and Religion 1550-1700". In John Whitney Hall (ed.). The Cambridge History of Japan. Vol. 4, Early Modern Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 378.

- ^ Addiss (1976), p. 11.

- ^ Lippit, Yukio. "Zenga: A Brief History". Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

Paintings

-

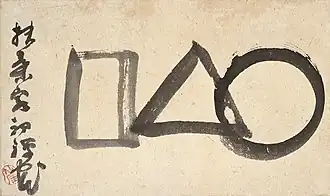

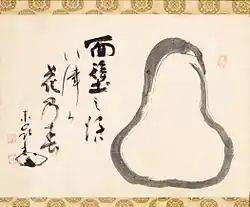

Sengai Gibon (1750-1837)

Sengai Gibon (1750-1837) -

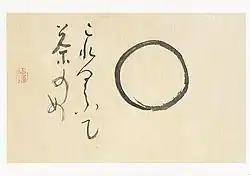

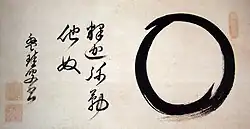

.jpg) The Character for Heart-Mind as an Enso - Daidō Bunka (Japan, 1680-1752)

The Character for Heart-Mind as an Enso - Daidō Bunka (Japan, 1680-1752) -

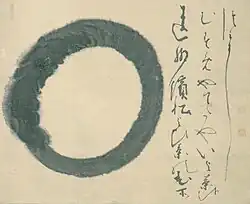

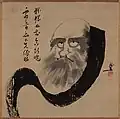

Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768)

Hakuin Ekaku (1685-1768) -

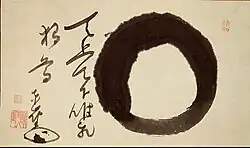

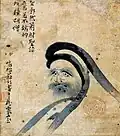

Torei Enji (1721-1792)

Torei Enji (1721-1792) -

Bankei Yōtaku (盤珪永琢; 1622-1693)

Bankei Yōtaku (盤珪永琢; 1622-1693)

-

Shunsō Shōshu (1752-1835)

-

Hakuin Ekaku (白隠 慧鶴, 1685-1768)

-

Tōrei Enji (Japan, 1721-1792

Tōrei Enji (Japan, 1721-1792 -

Setsuo 19th century

Setsuo 19th century -

Fūgai Ekun (1568-1650)

Fūgai Ekun (1568-1650)