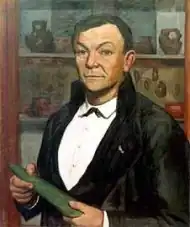

Zacharie Le Rouzic

Zacharie Le Rouzic (born 24 December 1864, Carnac; died 15 December 1939, Carnac)[1] was a French archaeologist and prehistorian, who devoted himself mainly to the study and preservation of megalithic sites in Morbihan, Brittany; he was also a writer on the folklore of the Carnac district.

Childhood

The last child in a family of nine whose father was a rag merchant, Zacharie Le Rouzic, despite his humble origins, attended the convent school in Carnac until the age of 10. Carnac having become a famous seaside town, he met foreign holidaymakers there as a child, such as the painter Théodore Valerio, whose artistic equipment he carried during his walks, and the archaeologist James Miln, who came to study the numerous megalithic sites of Carnac. Noting Le Rouzic's interest in his work, Miln taught him how to collect and classify the discovered pottery and Le Rouzic thus became his main collaborator, assisting in all his excavations. [2][3][4]

Career

After Miln's death in 1881 Le Rouzic became at the age of eighteen the caretaker of the J. Miln Museum, founded in 1882 by Robert Miln to present his brother James's collections to the public. After completing his military service in the Navy, he returned to his position at the museum, where he led tours during the tourist season, an activity he continued until his death. From 1887 to 1895, he enriched the museum's collections by buying finds from farmers in their fields and he began to systematically record the megalithic sites in the surrounding area, but without undertaking any excavations because he did not have the necessary financial means.[5] His activity was encouraged by Gustave de Closmadeuc, president of the Polymathic Society of Morbihan and excavator of several Morbihan sites (Carnac, Locmariaquer). In 1889, Closmadeuc entrusted him with the counting of the menhirs of the Carnac alignments.[2]

Le Rouzic was passionate about photography and photographed scenes of daily life (rural and coastal activities, weddings, costumes), natural and heritage sites, the images of which he sold in the form of postcards to passing tourists, an activity that was much more profitable than his salary as a museum caretaker alone. Around 1895, he met Charles Keller, who had a second home in Carnac; they became friends and Le Rouzic shared with him his interest in megaliths. From 1895, Keller subsidized the excavations of Le Rouzic, to whom the Polymathic Society had just entrusted the conservation and restoration of the megalithic monuments of Morbihan. Initially, Le Rouzic limited himself to resuming excavations on monuments that had already been explored or were too ruined and therefore neglected by his predecessors.[5] In 1900, he began excavating the Saint-Michel tumulus, which had been partially explored by the Polymathic Society in the 1860s, with funding from Keller and various American patrons. Le Rouzic excavated the tumulus for six years and published the excavation reports in 1932. He bought land near the site where he established his family home, called Kerdolmen,[a] and at the same time continued his photography and recording of the legends, tales, and customs of the Carnac region. Now recognized as a specialist in the megaliths of Morbihan, he was invited abroad (to Ireland and Wales) by his archaeologist colleagues.[2]

In 1910 he became official curator of the J. Miln Museum.[4] In 1917, at the age of 52, he enlisted to fight in the First World War, where he served in the 1st Artillery Regiment and was mentioned in dispatches. After the war, he resumed archaeological excavations at several sites (Manio, Carnac, Er Lannic) and trained Saint-Just Péquart and his wife. In 1926, he bequeathed his own collection of 3,000 archaeological objects to the J. Miln Museum.[2][6] The municipal council then added his name to the museum's name.[7] From 1927 onwards Le Rouzic, being ill, undertook no major excavation projects but only restorations of monuments.[8]

In 1933, he was appointed correspondent and then member of the historical monuments commission for Morbihan.[9] Between 1911 and 1938 he contributed to the registration and classification in the supplementary inventory of historical monuments of around 120 dolmens and menhirs, and to the excavation and restoration of around 130 monuments.[10] In 1935 he secured the return to Carnac of part of the collections of Paul du Châtellier which had been bought by the National Archaeological Museum, including objects from the excavations of Félix Gaillard, Arthur Martin and Louis Le Pontois.[9] Some of his restorations, for example those at Saint-Michel tumulus, Kercado, and Mane Roullarde, were contentious from the moment they were carried out.[11] Many of his re-erections of the fallen stones in the Carnac alignments are now considered to have been wrongly placed.[12] In 1937–1938, his restoration of the Table des Marchands, at the request of the commission headed by Abbé Breuil with whom he had an excellent relationship, caused a very significant controversy, first local and then national.[13]

In 1919, he became involved in politics, declaring himself "republican, democrat, secular and anticlerical" and contributed to the creation of the secular school and various secular social works in Carnac. He served as deputy mayor under his cousin Joseph Le Rouzic, and remained in that post until his death in 1939.[2]

Publications

His little Guide des monuments mégalithiques de Carnac et de Locmariaquer (Guide to the Megalithic Monuments of Carnac and Locmariaquer), intended for tourists, went through 18 editions between 1897 and 1975.[5] In 1901, he published a work entitled Les monuments mégalithiques de Carnac et Locmariaquer, leur âge, leur destination, which was translated into English in 1908 as The Megalithic Monuments of Carnac and Locmariaquer: Their Purpose and Age. In 1909, he was the author of a work entitled Carnac: Légendes, traditions, coutumes et contes du pays (Carnac: Legends, Traditions, Customs and Tales of the Country), devoted to popular traditions and Breton folklore, a work that has been frequently republished since.[9][14][b]

Zacharie Le Rouzic published numerous articles in the Bulletin de la Société polymathique du Morbihan and in archaeological journals such as the Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, the Revue des musées, the Revue pour l'avancement des Sciences, and the Revue archéologique.[4] In 1933–1934, he published two review articles in the journal Anthropologie, one devoted to a typology and chronology of prehistoric burials in Morbihan, and the other to the archaeological finds collected there. The chronology proposed by Le Rouzic was then very innovative and is now for the most part accepted.[c] Towards the end of his life, he planned to publish, in collaboration with the British anthropologist Vera Collum, an exhaustive summary work inventorying the megalithic monuments of the Carnac region, but he died before being able to achieve this.[15] Le Rouzic's preparatory notes for this work were published posthumously by his son-in-law Maurice Jacq with the help of the Société polymathique in 1965.[16]

Honours

Le Rouzic was created a Chevalier du Légion d'Honneur, an Officier de l'Instruction Publique, and an Officier du Mérite Agricole. He was granted the bronze medal of the École d'Anthropologie de Paris, the silver medal of the Société Française d'Archéologie, and the vermeil medal of the Institute Finisterien des recherches archéologiques. For his war service he was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Médaille Militaire.[17]

Notes

- ^ Integrated in 1922 into the hotel Le Tumulus located at the foot of the site.

- ^ The work was republished in 1912, 1924, 1928 and 1939, then after the author's death in 1954, 2000 and 2007.

- ^ Rouzic dated the low mounds to the Neolithic, and the short passage tombs and those covered by corbelling to the transition to the Copper Age, but he wrongly attributed the large Carnac tumuli to the Bronze Age.

Citations

- ^ Cabrol 1939, pp. 479–480.

- ^ a b c d e Laville, Grégoire (2023). Terre de mégalithes: Carnac et les rives du Morbihan (in French). Rennes: Éditions Ouest-France. pp. 95–97. ISBN 9782737388927. Retrieved 31 July 2025.

- ^ Richard, Nathalie; Viraben, Hadrien (17 January 2024). "The Work of a Dilettante or a Grand Amateur?". HAL Open Science. pp. 13–14. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ a b c Le Cam, Gaby (2006). "Zacharie Le Rouzic, enfant de Carnac, archéologue et… photographe" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société d'archéologie et d'histoire du Pays de Lorient (in French). 34: 93. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- ^ a b c Bailloud et al. 2009, pp. 39–41.

- ^ R. L. (January–June 1940). "Zacharie Le Rouzic (1864–1939)". Revue Archéologique. 6th series (in French). 15: 89. JSTOR 41755155.

- ^ "Séance du 24 février 1927". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France (in French). 1927. Retrieved 2 August 2025.

- ^ Bailloud et al. 2009, p. 44.

- ^ a b c Boujot, Christine; Vigier, Emmanuelle (2012). Carnac et environs: Architectures mégalithiques (in French). Paris: Patrimoine. p. 111. ISBN 9782757702062. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ Le Rouzic, Zacharie (May 1939). "Les monuments mégalithiques du Morbihan: causes de leur ruine et origine de leur restauration". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française (in French). 36 (5): 234–251. Retrieved 9 August 2025.

- ^ Guenin, G. (July–August 1939). "A propos des Monuments mégalithiques du Morbihan: quelques réflexions et suggestions". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française (in French). 36 (7/8): 337–351. Retrieved 10 August 2025.

- ^ Thom, A.; Thom, A. S. (2003) [1978]. Megalithic Remains in Britain and Brittany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780198581567. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ Bailloud et al. 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Le Rouzic, Zacharie (1908). The Megalithic Monuments of Carnac and Locmariaquer: Their Purpose and Age. Translated by Tapp, W. M. London: H. J. Hall. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Bailloud et al. 2009, p. 46.

- ^ Le Rouzic, Zacharie (1965). "Inventaire des monuments mégalithiques de la région de Carnac. L'arrondissement de Lorient". Bulletin de la Société polymathique du Morbihan (in French). 92: 3–88. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

- ^ Cabrol 1939, p. 482.

References

- Bailloud, Gérard; Boujot, Christine; Cassen, Serge; Le Roux, Charles-Tanguy (2009). Carnac, les premières architectures de pierre (in French). Paris: CNRS. ISBN 9782271068330. Retrieved 1 August 2025.

- Cabrol, Alexis (1939). "Nécrologie: Zacharie Le Rouzic (1864–1939)". Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française (in French). 36. Retrieved 12 August 2025.

External links

Media related to Zacharie Le Rouzic at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Zacharie Le Rouzic at Wikimedia Commons

Works related to Zacharie Le Rouzic at Wikisource

Works related to Zacharie Le Rouzic at Wikisource