Yevgeny Kiselyov

Yevgeny Kiselyov | |

|---|---|

Евгений Киселёв | |

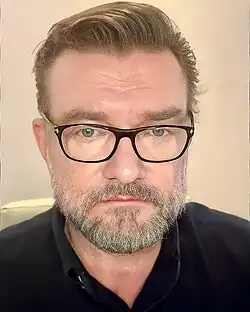

Kiselyov in 2023 | |

| Born | Yevgeny Alexeyevich Kiselyov 15 June 1956 |

| Nationality | Russian |

| Alma mater | Institute of Asian and African Countries |

| Organization(s) | NTV (1990s–2001) TV-6 (2001–02) |

| Awards | International Press Freedom Award (1995) |

Yevgeny Alexeyevich Kiselyov (Russian: Евгений Алексеевич Киселёв, Ukrainian: Євген Олексійович Кисельов; born 15 June 1956) is a Russian television journalist. As the host of the NTV weekly news show Itogi in the 1990s, he became one of the nation's best known television journalists, criticizing government corruption and President Boris Yeltsin. In 2001, he left NTV following its takeover by the state-controlled company Gazprom, serving briefly as general manager of TV-6 before the government refused to renew its broadcasting license in January 2002. He later moved to Ukraine, where he became a presenter of various political talk shows.[1][2]

Background

Kiselyov is the son of an aviation engineer. A student in Persian at Moscow State University, he later worked as an interpreter in Iran and Afghanistan during the Soviet–Afghan War. He began his broadcast career with the Persian service of Radio Moscow in 1984, moving to television three years later. He became famous in 1991 when he refused to report official Soviet news as the USSR was losing control of the Baltic states.[3]

Itogi host

Kiselyov was a "pioneering" television journalist in Russia in the 1990s after the dissolution of the Soviet Union,[4] and in 1997, the New York Times described him as "Russia's most prominent television journalist".[5]

During this period, he hosted the popular weekly news show Itogi ("Results") on the independent station NTV.[6] The show was modeled on the long-running US news program 60 Minutes.[3] Kiselyov described Itogi's politics as "anti-Communist, pro-reform and pro-democracy", and it specialized in investigating government corruption. However, critics stated that the show was "excessively politicized", and settled scores on behalf of the station's owner.[7]

In 1999, Itogi broadcast an episode in which Kiselyov broke new ground by lambasting the administration of Boris Yeltsin, describing them as "the family", an "insiders' code phrase" for Yeltsin and his small circle of advisers. He criticized them for handpicking the latest Cabinet, comparing Yeltsin's rule to that of the Roman emperor Caligula.[8]

Closure of independent stations

As NTV's managing director, Kiselyov was active in protests when a Russian court gave control of the station to the state-controlled company Gazprom,[9] describing the takeover as an attempt by the government of Vladimir Putin to suppress dissent.[10] In April 2001, he and several others were ousted from the board of directors by Gazprom. NTV's journalists condemned the cull, stating that the "ultimate goal of this meeting is the imposing of full political control over us".[11] Along with a number of NTV journalists, he moved to rival station TV-6.[10]

With the arrival of the NTV team, TV-6's ratings more than doubled. Kiselyov continued to report on sensitive topics including corruption and the conflict in Chechnya.[12] He also became the station's general manager. In January 2002, however, the station's broadcasting license expired and was given by the government to another company, forcing them off the air.[13] Kiselyov called it a "television coup" showing that the authorities' "single goal" was to "gag" the station. The government disputed his statement, saying that the non-renewal of TV-6's license was "purely a business decision".[14]

In March 2002, Kiselyov teamed with the Media-Socium Group, a group of pro-Putin businesspeople that included former prime minister Yevgeny Primakov, and was re-awarded the broadcasting license to the station. A BBC News analyst stated that the new political ownership was "likely to ensure the journalists do not ruffle too many feathers above".[15] The new station, TVS, soon ran into financial difficulties and quarrels between shareholders, and was closed by the government in June 2003 on the grounds of "viewers' interests".[16] Though viewed as less critical than its predecessor, it had been the last television station to criticize the Putin government. With the station's end, Nezavisimaya Gazeta called Russia "the one-channel country", stating that private television had once again disappeared, and Ekho Moskvy criticized the "complete state monopoly of country-wide channels".[17] Kiselyov stated that his priority following the closure was to find new jobs for the news staff, some of whom had now followed him through three television stations.[16]

Move to Ukraine

In 2008, Kiselyov moved to Ukraine.[4] He stated that he moved because working in Ukraine allowed him to be a true political journalist. "In Russia, there is no open political debate any more. The authorities are hermetically sealed, we can just hypothesize about the discussion going on inside ... Here [in Ukraine] you have access to tons of information, to almost any politician".[18] He also said that he felt Russian journalism had developed a culture of self-censorship.[4]

Since September 2009, Kiselyov hosted a sociopolitical talk show called Big-Time Politics with Yevgeny Kiselyov on Inter. Kiselyov presented his (Ukrainian) shows in Russian; his guests spoke Ukrainian or Russian.[19]

On 21 May 2010, the deputy head of the Administration of Ukraine Hanna Herman stated the wish, that Ukraine's most popular political talk shows be anchored only by Ukrainian journalists: "We are still victims to that imperial complex that 'everything coming from Moscow is good, everything Ukrainian is bad'".[2]

The viewership of Big-Time Politics dropped from 1 million in 2007 to 500,000 people in 2011, reflecting a general decline in interest in political talk shows.[20] In January 2013, Inter replaced Big-Time Politics with a political talk show hosted by Anna Bezulyk.[1] Kiselyov was from then on in charge of news production at Inter.[1] In the summer of 2016, Kiselyov left Inter.[21] He then moved to Pryamiy kanal to present the program "Results".[22][21] Kiselyov left Pryamiy kanal in the summer of 2019, and became the presenter of "Real Politics with Yevgeny Kiselyov" early 2020 on the channel Ukraine 24 (Україна 24).[22] Ukraine 24 stopped its activities in July 2022. On 27 October 2019, Kiselyov founded his self-named YouTube channel, with the current handle @evgeny.kiselev. As of 29 September 2023, the channel has 326,000 subscribers.[23]

Public position

Evgeny Kiselyov has a generally positive assessment of Boris Yeltsin's presidency and a sharply negative assessment of Vladimir Putin's activities in power. He stated that the only thing he disagreed with the first president of Russia was the choice of Putin as his successor.[24] In 2004, he became one of the founders of the 2008 Committee, a group of politicians and public figures who criticize President Putin.[25]

In the fall of 2004, he supported the Ukrainian Orange Revolution,[26] which he hasrepeatedly spoken about.[27]

In March 2014, in an interview regarding the annexation of Crimea, he sharply criticized Russia's foreign policy towards Ukraine, saying that he did not want to be involved in a country that was committing aggression against Ukraine, and that he was ashamed to be a Russian citizen.[28]

In September 2014, he signed a statement demanding "to stop the aggressive adventure: to withdraw Russian troops from the territory of Ukraine and to stop propaganda, material and military support to the separatists in Southeastern Ukraine."[29]

On June 10, 2016, he announced the initiation of a criminal case against himself in the Russian Federation because of statements in support of Nadezhda Savchenko.[30] According to the journalist, the case is under Article 205.2 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation ("Public calls for terrorist activities or public justification of terrorism") with a maximum penalty of seven years in prison. As part of this, the wife has already been interrogated and searched at her place of residence.[31] Against the background of these events, Yevgeny Kiselyov, in an open appeal to the President of Ukraine, Petro Poroshenko, called on the state level to resolve the issue of granting political asylum to Russian oppositionists to the regime of President Vladimir Putin.[32] On June 17, 2016, Yevgeny Kiselyov reported that Petro Poroshenko personally promised to assist him in helping Russian citizens who seek asylum in the country.

Kiselyov says about his religion: "I want to make a reservation: I do not belong to either the Russian Orthodox or the Catholic Church, I am an old—fashioned atheist and therefore I feel equidistant from both Francis and Kirill."[33]

On September 3, 2017, in an interview with the head of the Security Service of Ukraine, Vasyl Hrytsak, Kiselyov stated that Russian special services could actively use Middle Eastern refugees in Western Europe to carry out various provocations.[34]

Since February 2022, he has been a member of the Anti-War Committee of Russia.[35]

On April 5, 2022, the Russian Ministry of Justice added Kiselyov and journalist Matvey Ganapolsky to the list of individuals who are "foreign agents." They were the first people to be included in this list, rather than in the list of media outlets that are "foreign agents."[36] On July 15, the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia was put on the wanted list.[37]

On February 22, 2024, Rosfinmonitoring included him in the "list of extremists and terrorists"[38]

Criticism

Viktor Shenderovich — about Kiselyov's work in the Moscow News::

In the end, you won't be lost - you can find some other place to puff up your cheeks. You're a "brand"... and one last thing. Do you know what the main problem of Russian democracy is? Not in Putin, and not in the Chekists in general, and not in the nomenclature… The main problem is that ambiguous people like you are beginning to be associated with democracy and its values in the public consciousness.[39].

Maxim Sokolov on Kiselyov's position on Ukrainian television:

The example of Russian citizen E.A. Kiselyov, who calls on Kiev TV viewers to kidnap other Russian citizens in the form of hostage trafficking, shows that in the 21st century, an acute conflict of loyalties may well arise, after which there is room for only one loyalty. Which I have to prove with all my zeal. When choosing a new permanent residence, it is wise to keep in mind the incident of E.A. Kiselyov, so that the 21st century does not overtake the future emigrant all of a sudden.[40].

Assessing the role of E. Kiselyov in covering the 1999-2000 election campaign in Russia, Candidates of Philology and Associate professors of the Department of Periodicals at the Faculty of Journalism of Moscow State University L. O. Resnyanskaya and E. A. Voinova, and philologist O. I. Khvostunova noted:[41]

To warm up the mood and stimulate the activity of voters, two technologies that are still reliable in Russia were used — compromising and myth-making, or exorcism and the creation of God. The role of the shock forces in pumping information to citizens was assigned to the so-called analytical, author's programs of national channels. "Gladiators" S. Dorenko and N. Svanidze (ORT and RTR) against another "gladiator" E. Kiselyov (NTV) played "bad" and "good" guys in a script not written by them, covering up the fight and bargaining in the virtual space for dominance in the political economic sphere of the property-deprived elites and "letting off steam" of discontent with the authorities.

Family and personal life

- His father, Alexey Alexandrovich Kiselyov, is a metal engineer, winner of the Stalin Prize of the II degree.

- He is married for the second time to his classmate, Marina Gelievna Shakhova (pseudonym Masha Shakhova,[42] born in 1956), graduated from the Faculty of Journalism of Moscow State University.[42][43] She hosted the program "Dachniki", the producer of the program Fazenda, for the program on the TV channel Dachniki Shakhova received the TEFI-2002 award, as a designer she exhibited in the Small Manege.[42][44]

- Father—in-law - Geliy Alekseevich Shakhov.[49] He was one of the heads of the USSR State Television and Radio Station, a journalist, was a correspondent in Kenya, former editor-in-chief of Foreign Broadcasting in the USA and Great Britain, shortly before his death translated Kerensky's memoirs, which were published in the early 1990s, met with Alexander Kerensky in the USA in the early 1960s.[43][50][51]

- Mother—in-law - Erna Yakovlevna Shakhova-[44] She worked as a translator for the publishing house "Khudozhestvennaya Literatura" and the NTV television company, was the lead editor of the editorial office of foreign literature of the publishing house "Khudozhestvennaya Literatura" and received the title of Honored Worker of Culture of the Russian Federation in 1996.[43][46][52][53]

Awards

- Order of the Cross of the Land of Mary, 4th degree (February 5, 2004, Estonia)[54].

- Committee to Protect Journalists International Press Freedom Award (1995)[55].

- TEFI Award for the best television analytical program (Itogi) (1996).

- Laureate of the Telegrand award, presented for contribution to the development of Russian television and radio broadcasting (1999)[56].

- Laureate of the TEFI award for the talk show "Voice of the People". In the same year he was awarded the Golden Pen of Russia award by the Union of Journalists of the Russian Federation[57] (2000).

References

- ^ a b c Shuster back at Inter channel, Kyiv Post (19 February 2013)

- ^ a b "Herman wants anchorman Savik Shuster replaced by Ukrainian". zik.ua. 21 May 2010. Archived from the original on 22 July 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b Robert Thomas Teske (1980). Votive Offerings Among Greek-Philadelphians: A Ritual Perspective. Ayer Publishing. pp. 242–3. ISBN 9780405133251.

- ^ a b c Clifford J. Levy (23 January 2010). "TV Refugees From Moscow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Alessandra Stanley (20 February 1997). "Tough Side of Albright Is Awaited in Moscow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Michael Specter (24 December 1995). "Russia's New Style of Hero". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Michael R. Gordon (16 March 1997). "Russian Media, Free of One Master, Greet Another". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Celestine Bohlen (5 September 1999). "In Russia, a Power Play Acted Out on Television". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Michael Wines (8 April 2001). "TV Takeover Stirs Protest in Moscow". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b Michael Wines (15 April 2001). "TV Workers End Standoff at Network in Russia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Russian TV station loses freedom". BBC News. 3 April 2001. Archived from the original on 8 November 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Fred Weir (23 January 2002). "Did business or politics silence Russian TV station?". The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Michael Wines (23 January 2002). "Russians Find Suspicions Fly As Network Goes Off Air". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Russian station taken off air". BBC News. 22 January 2002. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Pro-Kremlin group wins TV channel". BBC News. 27 March 2002. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Russia pulls plug on critical TV". BBC News. 22 June 2003. Archived from the original on 26 April 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "TV closure sparks 'Soviet' jibe". BBC News. 23 June 2003. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Russian journalists find haven in Ukraine". Hurriyet Daily News. 20 July 2009. Archived from the original on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ Chrystia Freeland (11 July 2009). "Russia's Free Media Find a Haven in Ukraine". The Financial Times. Retrieved 24 August 2012.(subscription required)

- ^ Yuliya Raskevich (18 November 2011). "Tuning Out". Kyiv Post. Archived from the original on 19 August 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Євгеній Кисельов: Мій офіційний статус – біженець". 5 June 2018.

- ^ a b "Мільярдер Ахметов "купив" для свого нового телеканалу відомого російського ведучого". 29 December 2019.

- ^ "Евгений Киселев". YouTube. 27 October 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ "Евгений Киселёв: «Не могу простить Ельцину одного — назначения Путина преемником»". Факты и комментарии. 21 April 2017. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "Комитет "2008 СВОБОДНЫЙ ВЫБОР" / Участники". 5 February 2007. Archived from the original on 5 February 2007. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ "Евгений Киселёв: "Мой учитель при слове «концепция» говорил, что хватается за револьвер"". Свободная пресса. 21 September 2009. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "Евгений Киселёв: «Хороший сценарий ждёт Россию, только если прилетит "черный лебедь"»". Открытая Россия. 5 November 2016. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Дмитрий Волчек (30 March 2014). "Бывший директор телекомпании НТВ Евгений Киселёв – о Майдане, выборах президента Украины и кремлёвской телепропаганде". www.svoboda.org. Archived from the original on 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ "Заявление «Круглого стола 12 декабря» к Маршу Мира 21-го сентября". Archived from the original on 16 September 2014. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- ^ "Открытое письмо президенту Украины Петру Порошенко". m.nv.ua. 10 June 2016. Archived from the original on 14 June 2016. Retrieved 12 June 2016.

- ^ На Евгения Киселёва завели дело о призывах к терроризму Archived 2016-06-11 at the Wayback Machine «Meduza», 10.06.2016

- ^ ФСБ переслідує Євгена Кисельова — він просить у Порошенка захисту для себе і для російських опозиціонерів Archived 2016-08-07 at the Wayback Machine «Детектор Медиа», 10.06.2016

- ^ ""Если Евтушенко против колхозов, то я – за"" (in Russian). Эхо Москвы. 8 February 2016. Archived from the original on 11 February 2016. Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Запись". YouTube. Archived from the original on 27 April 2022. Retrieved 5 July 2022.

- ^ "Антивоенный комитет России". Archived from the original on 17 March 2022. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- ^ "Журналистов Евгения Киселева и Матвея Ганапольского в России внесли в новый реестр «иноагентов». В чем отличия?". BBC. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ "МВД России объявило в розыск журналиста Евгения Киселева". Комсомольская правда. Archived from the original on 18 July 2022. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Росфинмониторинг включил в перечень экстремистов журналиста Евгения Киселева". Archived from the original on 22 February 2024. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ "Евгению Киселёву, бренду и человеку". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ "Евгений Киселёв призывает похищать граждан России". Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 14 March 2016.

- ^ Реснянская Л. Л., Воинова Е. А., Хвостунова О. И. СМИ и политика: Учебное пособие для студентов вузов. — М., Аспект Пресс, 2007. — С. 79. ISBN 978-5-7567-0455-6

- ^ a b c "Аргументы и факты — Зачем Маша Шахова спасает пауков? — «АиФ Суперзвёзды», № 22 (52) от 16.11.2004". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ a b c ТЕЛЕНЕДЕЛЯ — Взгляд назад — Маша Шахова: муж говорит, что я стала циничной

- ^ a b Маша Шахова: «Человек в своем доме должен быть счастлив!»

- ^ "Киселёв: Не осталось ни одной живой души в моем окружении, которая бы сказала «порву за Путина»". Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ a b Евгений Киселёв прожил с женой в два раза дольше, чем с мамой

- ^ "Актриса Маруся Фомина выходит замуж за продюсера Алексея Киселёва". Archived from the original on 8 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Как Алексей Киселёв породнил мир кино, телевидения и театра". Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- ^ "Радиостанция «Эхо Москвы» / Передачи / Интервью / Понедельник, 14.01.2002: Евгений Киселёв". Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ "Легенды Иновещания". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 5 November 2015.

- ^ "Радиостанция «Эхо Москвы» / Передачи / Архив передач / Наше все / Воскресенье, 23.12.2007: Генрих Боровик". Archived from the original on 1 June 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ Указ Президента РФ от 7 июня 1996 г. № 844 «О награждении государственными наградами Российской Федерации»

- ^ "ШАХОВА Мария Гельевна — Биография — БД «Лабиринт»". Archived from the original on 7 December 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2011.

- ^ "Jevgeni Kisseljov. Teenetemärkide kavalerid". Archived from the original on 28 December 2022. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- ^ "Journalists Receive 1996 Press Freedom Awards". Committee to Protect Journalists. Archived from the original on 11 August 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2012.

- ^ "Евгений Киселёв стал "телеграндом"". Ведомости. 30 December 1999. Archived from the original on 18 October 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ "Лауреаты премий Союза журналистов России за 1996-99 годы". Союз журналистов России. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2016.