Woodlawn Plantation (Jefferson County, Mississippi)

| Woodlawn Plantation | |

|---|---|

Woodlawn Plantation owner's residence circa 1813 | |

| General information | |

| Status | Private Residence |

| Type | Plantation house in the Southern United States |

| Architectural style | Federal architecture |

| Location | Jefferson County, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Construction started | approximately 1813 |

| Completed | approximately 1815 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | Two |

Woodlawn was a deep-south, cotton plantation in Jefferson County, Mississippi circa 1813.[1]

Location

The Woodlawn Plantation land with its original owner's residence is located on the north bank of Coles Creek, seven miles south of the Mississippi River town of Rodney, in Jefferson County, Mississippi.[2] Woodlawn was also just a few miles to the northwest of Old Greenville, Mississippi, which was on the Natchez Trace.

Creation and Ownership History

Woodlawn was created by cotton planter, and slaveholding entrepreneur David Hunt (1779–1861) approximately when he began having his Woodlawn residence built circa 1813.[2][1] As shown on various maps, David Hunt's Woodlawn residence was built on the land at T9N-R1E, sections 6 and 8.[1] Thus, Hunt would have owned this just-under 300 acre site by 1813. According to the bureau of land management website, in 1820 Hunt purchased the rest of the adjoining land for Woodlawn Plantation at T9N-R1W, sections 7, 3/4 of 9, 23, and 24; and T10N-R1W section 49[3][4] The previous land parcels add up to approximately 1,500 to 1,600 acres, which adjoin both the Calviton Plantation site and the Huntley Plantation site.[4][1]

After David and his wife Ann Ferguson married in 1816, they used Woodlawn as their primary residence for the rest of their lives.[1][2] David and Ann had fourteen children at Woodlawn.[2] Many of them lived to adulthood, and married on Woodlawn.[2]

The Wagner's bought Woodlawn after the Civil War.[1] It was about 1,500 to 1,600 acres.[1] It was then increased to 2,200 acres.[1]

Operation as an Antebellum Plantation

Woodlawn's cash crop was cotton.[5] Hunt believed in making his plantations self-sufficient.[5] Thus, he did not allocate all of his plantation land for cotton.[5] Cattle, sheep, hogs, horses and mules were raised on his plantations.[2] Mainly on his home plantation, Woodlawn, he had a program of home industry and trades to help supply his plantations.[2] Carpentry, black-smithing, thread spinning, cloth weaving, clothes making, sock knitting, leather tanning, and shoemaking were carried out on Woodlawn Plantation by the enslaved Africans.[5][2] He also ensured that his crops were shifted to rebuild the soil.[5] He had to purchase the salt and iron needed on his plantations, though.[5]

In December, 1861 Woodlawn had the following stock and plantation supplies.[6] 132 sheep, 10 beef cattle, 10 yolk of oxen, 49 head of dairy cattle, 9 calves, 13 mares, 4 colts, 7 mule colts, 8 yearling colts, 28 mules, 4 plough horses, 1 stallion, 2 wagon horses, 11 carriage horses, 1 jack, 160 hogs, 2,700 bushels corn, 10,000 pounds fodder, 50 bushels peas, 1 cart, 3 ox wagons, 2 horse wagons, 10 ox yokes and chains, furniture of overseer's house, 90 fattening hogs, 1 lott carpenter tools, 13 axes, 40 hoes, 12 spades & shovels, 6 iron wedges, 22 ploughs, 15 harrows, 4 cotton drills, 6 sweeps, 2 separators, 2 large harrows, blacksmith tools and irons, lott of plough fixtures.[6]

David Hunt's enslaved African ownership numbers (thought to be for Woodlawn) from census data and other sources follow.

- 1808 - Jefferson County, MS, 11 enslaved (census when David was living on Calviton Plantation, which adjoined the land that became Woodlawn, after his 1808 marriage to Mary Calvit)

- 1810 - Jefferson County, MS, 24 enslaved[7]

- 1816 - Jefferson County, MS, 31 enslaved (census when David was living on Woodlawn after his marriage to Ann Ferguson)

- 1820 - 50 enslaved shared between 636 acres on Coles Creek (referred to as the Hunt Place - probably Woodlawn) and 880 acres on Black Creek (Black Creek probably didn't need many of these 50 enslaved, because it was mainly a big cypress swamp - valuable for its lumber and surely as a place for hogs to fatten up before the winter slaughter.)[7]

- 1861 - Woodlawn, 123 enslaved[6]

From 1800 to 1811, Hunt's money to expand his cotton planting in Jefferson County came from working for his very successful businessman Uncle Abijah - first at $200 per year as a store clerk in Old Greenville and soon at $3,000 per year with a much larger role in the Abijah Hunt and Elijah Smith firm - and also from reinvesting the profits from his cotton crops.[2] Hunt was said to be very frugal.

At his uncle Abijah's 1811 death, Hunt did not inherit but about $300 of his bachelor uncle's $36,000 personal estate, which consisted of about 60 enslaved, livestock and equipment on two plantations, household furnishings, etc. However, he did inherit all of his uncle's real estate - two plantations (Huntley in Jefferson County, and the Abijah Hunt plantation adjacent to Port Gibson in Claiborne County, Mississippi) a house in Old Greenville, over 10,000 acres of land in the Natchez District (Adams, Franklin, Jefferson and Claiborne Counties and Concordia and Tensas Parishes) and Cincinnati (where Uncle Abijah started out in business), and his uncle's share of the Hunt and Smith firm. The firm owned at least three general stores on the Natchez Trace (in Natchez, Old Greenville, and the Grindstone Ford), at least one public cotton gin in Old Greenville, and operated a cotton brokerage.[2] Cotton brokers provided other services for planters such as buying and selling slaves for them.

Without this inheritance, David would have probably never owned much more than Woodlawn Plantation. He gradually bought out the other investors in the Hunt and Smith firm, closed it and sold the assets at a profit. He invested the money in a Claiborne County plantation (probably the one he inherited from his Uncle), which he later sold (Hunt didn't have slaves in Claiborne County later on). The frugal Hunt got richer and richer as he bought and sold land and slaves, and as he kept creating plantations. He had a house somewhere in Natchez, spent many summers in Lexington, Kentucky (the richer planters took their families north in summer to escape the heat and deadly yellow fever), once travelled by ship to New York, but mostly lived on Woodlawn.

Hunt died in 1861 with seven plantations (Woodlawn, Black Creek, Southside and Brick Quarters, and Fatlands in Jefferson County; Hole-in-the-Wall and Argyle just across the Mississippi River near Waterproof, Louisiana; and Wilderness on the Mississippi River in Issaquena County, Mississippi; and about 700 enslaved. Furthermore, he helped five of his adult children and their spouses finance their own plantations and residential estates (Homewood, and Lansdowne hunting estates near Natchez; Oakwood, Calviton, Wilkin Place, and Huntley Plantations in Jefferson County, Mississippi; Fairland, Georgiana, and Lockwood Plantations in Issaquena County, Mississippi; and Arcola Plantation near Waterproof, Louisiana) with about 800 enslaved. Woodlawn (David's home), Huntley (David's son George's home), and Calviton (David's son Abijah's home) were adjoining and were essentially one big plantation. Oakwood (David's daughter Mary Ann's home) was on the way south from Woodlawn to Natchez. Homewood (David's daughter Catherine's home, and Lansdown (David's daughter Charlotte's home) adjoined on the northern suburbs of Natchez. These Hunt family home plantations were all near but not right on the old Natchez Trace. The families that Hunt and his children married into thoroughly integrated them into the planter elite of the Natchez District.

The following are some details about Hunt's enslaved in Jefferson County.

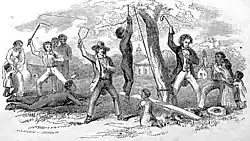

- Peter Brown was an enslaved African on Woodlawn Plantation, who was owned by David and Ann Hunt.[8] He was born March 1, 1852 on Woodlawn Plantation. His parents were Jane and William Brown.[8] One set of his grandparents were Sofa and Peter Bane, who also lived on Woodlawn.[8] Some of his siblings were Jonas, Sofa, Peter, Alice, Isaac and Jacob.[8] As a child he recalled hearing the enslaved being staked to the ground on their stomachs and bull whipped morning after morning by David Hunt and the overseers.[8] He stated that the enslaved were overworked.[8]

- Cyrus Bellus was born in 1865 in Jefferson County.[9] His parents, Cyrus and Matilda Bellus, were enslaved by David Hunt.[9] His father's parents were John and Dinah Major, who were owned by David Hunt.[9] His mother's parents were Annie and Stephen Hall.[9] He said his parents were field hands.[9] The men had to pick 400 pounds of cotton and the women had to pick 300 pounds of cotton in a day.[9] If they didn't do it, they were whipped by the overseer.[9] He said that Hunt didn't know what it was to buy shoes for the enslaved.[9] He said they had tanning vats to make the leather, so that they could make their own shoes.[9] He also said that the enslaved spun thread and wove cloth with which to make their clothes, and that they knitted socks.[9] He said that the enslaved sometimes worked all night at this.[9] According to David Hunt's son Dunbar, this program of home industry to provide most of the supplies for all of the family plantations was mainly carried out on David's home plantation of Woodlawn.[2] The enslaved were allowed to have fun during certain hours when they would play fiddles, sing, dance and have wrestling matches.[9] They had to turn a kettle over in their cabin to keep their religious praying and singing from being heard outside.[9] They lived in one room log houses with one window and one door.[9] Each was big enough for one family.[9] The working age enslaved were each given four pounds of meat and a peck of meal per week.[9] They ate before sunrise in their cabins and again in their cabins at seven or eight at night.[9] The children were fed during the day with food from the big house by the enslaved who were too old to work.[9] After the Civil War Cyrus went to a Jefferson County school called Dobbins Bridge for three years.[9] He stopped at age 15 and worked as a share cropper until he was 26.[9] Then he moved to Wilderness Plantation - probably the Hunt's Issaquena County, Mississippi Wilderness Plantation, which was right on the Mississippi River.[9] Then he moved on to Arkansas.[9]

- Tilde (short for Matilda) was enslaved on Woodlawn Plantation.[10] She moved to 287 Jackson Avenue (the street has since been renumbered) in the Garden District of New Orleans in about 1865 to work as a nurse for David Hunt's daughter Elizabeth (Hunt) Ogden's children when she married William F. Ogden that year.[10] It was a large house on the corner of Jackson and Carondelet Street.[10] Tilde was referred to as a girl who slept in the nursery with the children, and it was written that Elizabeth took charge of her in every way.[10] The live-in servants were a butler, cook, maid and nurse.[10] Someone came from outside the residence to do the washing and ironing.[10] Elizabeth once sold some of her diamonds to take her family on a trip to Niagara Falls.[10] Tilde went to Niagra Falls with them.[10] Tilde later married in New Orleans and moved on.[10]

- The 1861 property appraisal taken after David Hunt's death lists his approximately 375 Jefferson County enslaved by name and value.[6] They lived on David Hunt's Woodlawn, Fatlands, Brick Quarters (also known as Southside and Brick Quarters), which were in close proximity, and Black Creek Plantation.[6] It is highly likely that the partial list below includes most of the people mentioned above.[6]

| Woodlawn 123 enslaved | Fatlands 121 enslaved | Brick Quarters 128 enslaved | Black Creek 3 enslaved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peter, age 15, $1,000 | John, $1,000 | Cyrus 1,200 | |

| Jane, age 35, $700 | Dinah, $800 | Matilda, $500 | |

| Peter, age 4, $200 | Peter, $800 | Anna, $100 | |

| Jacob, age 9, $400 | Sophy, $800 | Stephen, $100 | |

| Isaac, age 8, $400 | Stephen, $50 | William, $800 | |

| Matilda, age 6, $300 | Ann, $100 | Alice, $50 | |

| Matilda, age 20, $800 | |||

| Ann and Infant, age 48, $500 |

Twelve Years a Slave is a book (full text is available for free at the Project Gutenburg website) that describes what life was like for the enslaved, such as the ones owned by the Hunts.

Owner's Residence

The house, begun in 1813, took the place of a log house; and was constructed from cypress logs, which were sawed into suitable building material on the plantation.[1] It was still not totally complete by 1815.[2] The structure rested on brick pillars.[1] The first floor originally had a center hall with one room on each side.[1] This floor was later changed to have two rooms on each side of the center hall (a parlor, a dining room, and two bedrooms).[1] A stairway at the rear of the center hall led to the second floor.[1] The second floor originally had a small cloakroom to the right of the stairs.[1] The rest was one large room, used as a ballroom.[1] The ballroom was later partitioned off into three bedrooms, which made four rooms on that floor including the cloakroom.[1]

The first floor rooms were plastered.[1] The second floor had walls that were just rough boards with wainscoting.[1] The fireplace mantels were wooden with a distinctive design.[1] The house had a small portico on the front and a porch that ran the full length of the rear.[1] There were originally three cisterns around the house.[1] Food was passed through the dining room window from the separate kitchen building to the right of the house - with no door ever being installed.[1]

In December, 1861 the owner's residence, kitchen (and store room) and probably a carriage house on Woodlawn had the following.[6]

- parlor furniture

- dining room furniture

- hall furniture

- furniture for 2 downstairs bedrooms

- furniture for 5 upstairs bedrooms

- 2 entries up stairs furniture

- kitchen furniture

- 10 barrels molasses

- 8 sacks salt

- 1,000 pounds meat

- 1 loom

- 2 carriages with harnesses.[6]

See also

- Homewood Plantation (Natchez, Mississippi)

- Lansdowne (Natchez, Mississippi)

- David Hunt (planter)

- Abijah Hunt

- List of plantations in Mississippi

- List of the oldest buildings in Mississippi

- Twelve Years a Slave

- Plantation complexes in the Southern United States

- African-American history

- American gentry

- Atlantic slave trade

- Casa-Grande & Senzala (similar concept in Brazilian plantations)

- History of the Southern United States

- Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation in 1838–1839

- List of plantations in the United States

- Lost Cause of the Confederacy

- Plain Folk of the Old South (1949 book by historian Frank Lawrence Owsley)

- Plantation-era songs

- Plantation house

- Plantation tradition (genre of literature)

- Plantations of Leon County (Florida)

- Planter class

- Sharecropping in the United States

- Slavery at Tuckahoe plantation

- Slavery in the United States

- Treatment of slaves in the United States

- White supremacy

- Commons:Category:Old maps of plantations in the United States

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Logan, Marie T. (1980). Mississippi-Louisiana Border Country: Revised Edition (Second ed.). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Claitor's Publishing Division. pp. 142, 143, 144, 153, 154.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hunt, Dunbar (May 29, 1908). "Sketch of David Hunt, November 12, 1906". Fayette Chronicle. XLI (35).

- ^ Tobin, Edgar. "Mississippi Plantations and Antebellum Homes". MSGW. Retrieved 26 March 2025.

- ^ a b Government, Federal. "Search Documents". Government Land Office Records. Government. Retrieved 13 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Kane, Harnett T. Natchez on the Mississippi. New York: Bonanza Books. pp. 174–189.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jefferson County. ""Mississippi Probate Records, 1781-1930" Catalog: Probate records, 1800-1930 Probate records v. H 1859-1866". Family Search. Family Search. Retrieved 14 February 2025.

- ^ a b "An Alphabetical List of Slaveowners of Jefferson County Who Owned 20 or more slaves (1820)". The Rodney Telegraph. 0ne (Five). 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Brown, Peter. "SLAVE NARRATIVES A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves". Gutenberg.org. Federal Writers Project. Retrieved 10 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Bellus, Cyrus. "SLAVE NARRATIVES A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews with Former Slaves". Gutenberg.org. Federal Writers Project. Retrieved 10 April 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Anderson, Elizabeth Ogden (Reed). "My Mother - A Southern Saga". A Family Account.