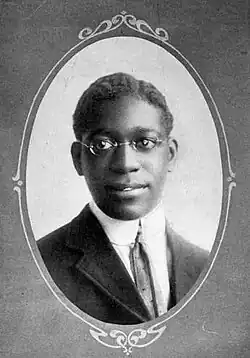

William L. Patterson

William Lorenzo Patterson (August 27, 1891 – March 5, 1980) was an African-American leader in the Communist Party USA and head of the International Labor Defense, a group offering legal representation to communists, trade unionists, and African Americans in cases involving alleged racial or political persecution. He was perhaps best known for submitting a petition to the UN in 1951, accusing the U.S. government of complicity in genocide against the Negro people.[1]

Early life

William Lorenzo Patterson was born August 27, 1891, in San Francisco, California.[2] His father, James Edward Patterson, originally hailed from the island of St. Vincent, in the British West Indies.[2] His mother, Mary Galt Patterson, had been born a slave in the state of Virginia and was the daughter of the organizer of a black volunteer regiment that fought in the Union Army during the American Civil War.[2]

Patterson's father was a Seventh-day Adventist missionary to Tahiti and he spent extensive time there, with the rest of the family moving between the California cities of Oakland and Mill Valley, where William attended public schools.[2]

In 1911, Patterson was the first African-American graduate of Tamalpais High School, in Mill Valley. In the school's yearbook, he stated an ambition "to be a second Booker T. Washington."[3] After graduation, Patterson supported himself by working as a laborer in railroad dining cars and on boats that sailed along the Pacific coast.[2] He saved enough money to enroll at University of California, Berkeley but was expelled during World War I for refusal to participate in compulsory military training.[2]

Deciding to set his sights on becoming a lawyer, Patterson entered Hastings College of Law, from which he graduated in 1919.[2] After failing the California State Bar Exam, he opted to pursue emigration to Liberia; he took a job as a cook on a mail ship to England as a means to that end.[2] He found, however, that his inquiries about Liberian emigration were rebuffed in England because of his lack of the artisan skills needed at the time in the African country. Determined to return to the U.S., he landed in New York and gained employment as a longshoreman.[2]

Patterson was able to put his college degree to use by getting hired as a law clerk. He helped write legal briefs and studied for the New York State Bar Exam, which he passed in 1924.[2] Meanwhile, he married his first wife, the former Minnie Summer, and made numerous personal acquaintances in the booming Harlem Renaissance.[2] After a divorce in 1928, he married Vera Gorohovskaya in 1929, with whom he had two daughters.[2] In September 1940, Patterson married for a third time, to Louise Thompson.[4] She was a left-wing activist with a long association with the poet Langston Hughes. On March 15, 1943, the Pattersons had their only child, MaryLouise Patterson, in Chicago, IL.

Political activism

One of Patterson's New York friends was the radical political activist Richard B. Moore, who persuaded Patterson to put his legal skills to work in defense of the Italian immigrant anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti. They had been convicted of murder in a controversial and highly politicized Massachusetts trial.[2] On August 22, 1927, Patterson was among the 156 persons arrested for protesting the executions of Sacco and Vanzetti.[5]

Patterson joined the Workers (Communist) Party in 1943,[6] and became head of the International Labor Defense (ILD), a communist legal advocacy organization.

He was also active in the Civil Rights Congress, which succeeded the ILD. In 1951, he went to a United Nations meeting in Paris and presented a petition titled We Charge Genocide; it accused the U.S. federal government of complicity in genocide for failing to pass legislation or prosecute persons responsible for lynching, most of whose victims were black men. Paul Robeson submitted the same petition to the UN in New York City.[7] After Patterson returned from Paris, the U.S. Department of State revoked his passport and barred him from further travel abroad.[8]

In 1971, he published his autobiography, The Man Who Cried Genocide.

Death and legacy

On March 5, 1980, after a prolonged illness, William Patterson died at Union Hospital in the Bronx. He was 88.[9]

Patterson's papers, prefaced by a brief biography, are housed at Howard University.[10]

Bibliography

- The Communist Position on the Negro Question. Contributor. New York: New Century Publishers, 1947.

- We Demand Freedom. New York: Civil Rights Congress, 1951.

- We Charge Genocide: The Historic Petition to the United Nations for Relief from a Crime of the United States Government against the Negro People. Editor. New York: Civil Rights Congress, 1951.

- A People's Alternative to Mayor Wagner's Tax Program. New York: 1963.

- Negro Liberation: A Goal for All Americans. New York: New Currents Publishers, 1964.

- Ben Davis: Crusader for Negro Freedom and Socialism. New York: New Outlook Publishers, 1967.

- In Honor of Paul Robeson: Excerpts of a Speech by William L. Patterson. New York: Communist Party USA, n.d. [1969].

- Some Aspects of the Black Liberation Struggle: Two Lectures. With Claude Lightfoot. New York: Black Liberation Commission, CPUSA, n.d. [1969].

- Four Score Years in Freedom's Fight: A Tribute to William L. Patterson on the Occasion of his 80th Birthday, Chicago, Illinois, October 22, 1971. Contributor, with Claude Lightfoot. New York: New Outlook Publishers, 1972.

- The Man Who Cried Genocide: An Autobiography. New York: International Publishers, 1971.

References

- ^ "(1951) We Charge Genocide". BlackPast.org. July 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Staff, "Biography", Finding Aid to the William Patterson Papers, Manuscript Division, Howard University, 2015.

- ^ Tamalpais Graduate, 1911, Tamalpais Union High School, Mill Valley, California

- ^ Gilyard, Keith (2017). Louise Thompson Patterson: A Life of Struggle for Justice. Duke University Press. p. 143. ISBN 978-0822369851.

- ^ "Sacco Aftermath". TIME. September 5, 1927. Archived from the original on July 27, 2009.

For "sauntering and loitering" in front of the State House in Boston, 156 men and women were arraigned, found guilty. All but six were fined $5 and paid the fine. The others— Edna St. Vincent Millay, poet; Ellen Hayes, retired Wellesley College professor; John Howard Lawson, playwright; William Patterson, Negro lawyer; Ela Reeve Bloor and Catherine Huntington, liberal gentlewomen—were fined $10.

- ^ Horne, Gerald (2013). Black Revolutionary: William Patterson and the Globalization of the African American Freedom Struggle. University of Illinois Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0252037924.

- ^ "Dec. 17, 1951: 'We Charge Genocide' Petition Submitted to United Nations". Zinn Education Project. December 18, 2024.

- ^ Glenn, Susan A. "'We Charge Genocide': The 1951 Black Lives Matter Campaign". University of Washington Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ Ledbetter, Les (March 7, 1980). "William Patterson, Lawyer, Dead at 89. Activist Fought for Black Causes. Joined With Paul Robeson in Accusing U.S. at U.N. Opened Harlem Law Office". The New York Times.

- ^ Finding Aid to the William Patterson Papers, Manuscript Division, Howard University, Oct. 1, 2015.

Further reading

- Horne, Gerald (2013). Black Revolutionary: William Patterson and the Globalization of the African American Freedom Struggle. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252037924.

- Howard, Walter T. (2013). We Shall Be Free!: Black Communist Protests in Seven Voices. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1439908594.