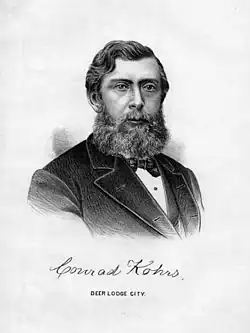

William A. Clark

William Clark | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Senator from Montana | |

| In office March 4, 1901 – March 3, 1907 | |

| Preceded by | Thomas H. Carter |

| Succeeded by | Joseph M. Dixon |

| In office March 4, 1899 – May 15, 1900 | |

| Preceded by | Lee Mantle |

| Succeeded by | Paris Gibson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | William Andrews Clark January 8, 1839 Connellsville, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | March 2, 1925 (aged 86) New York City, U.S. |

| Resting place | Woodlawn Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Katherine Stauffer

(m. 1869; died 1893)Anna La Chapelle (m. 1901) |

| Children | 9, five lived to adulthood: Mary Joaquina, Charles, Katherine Louise, William, Huguette |

| Education | Iowa Wesleyan University Columbia_University |

| Signature |  |

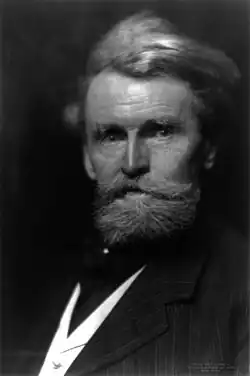

William Andrews Clark Sr. (January 8, 1839 – March 2, 1925) was an American entrepreneur, involved with mining, banking, land_development commercial sales and farming/timber enterprises, and railroads, as well as a U.S. Senator.[1][2]

Biography

Clark was born in Connellsville, Pennsylvania in 1839. He moved with his family to Iowa in 1856 where he taught school and studied law at Iowa Wesleyan College. In 1862, he traveled west to become a miner.[3] After working in quartz mines in Colorado, in 1863 Clark made his way to new gold fields to find his fortune in the Montana gold rush.

He settled in the capital of Montana Territory, Bannack, Montana, and began placer mining. Though his claim paid only moderately, Clark took on additional grunt work and invested his earnings in becoming a trader, driving mules back and forth between Salt Lake City and the boomtowns of Montana to transport eggs and other basic supplies. He undertook mail carrying contracts and ferried post from Walla Walla, Washington to Missoula, Montana for three years with his brothers.[4]

Clark would next expand into banking in Deer Lodge, Montana. His bank foreclosed on many properties during the mineral busts, and Clark became more and more invested into mining. Mr. Clark took his young family to New York City in the 1870s, and studied mining and minerology at Columbia University in New York City.[5] He travelled extensively in all areas between coasts of the United States and Hawaii as well as yearly or twice yearly trips to Europe. He made a fortune with copper mining, smelters, electric power companies, newspapers, railroads (trolley lines around Butte and the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad from Salt Lake City, Utah to San Pedro and Los Angeles, California), and many other businesses, becoming known as one of three "Copper Kings" of Butte, Montana, along with Marcus Daly and F. Augustus Heinze.

The November 1903 Congressional Directory notes that Clark "was a major of a battalion that pursued Chief Joseph and his band in the Nez Perces invasion of 1877."[6]

He died on March 2, 1925, and is interred in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York City.

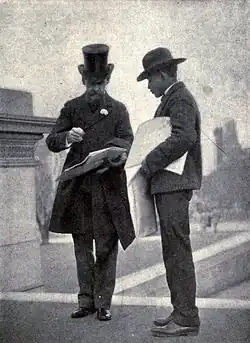

Political career

Clark served as president of both Montana state constitutional conventions in 1884 and 1889.

Clark was the President of Montana Constitutional Conventions of 1884 and 1889.[7] Clark yearned to be a statesman and used his newspaper, the Butte Miner, to push his political ambitions. At this time, Butte was one of the largest cities in the West. He became a hero in Helena, Montana, by campaigning for its selection as the state capital instead of Anaconda. This battle for the placement of the capital had subtle Irish vs. English, Catholic vs. Protestant, and non-Masonic vs. Masonic elements.

Clark's long-standing dream of becoming a United States senator resulted in scandal in 1899 when it was revealed that he bribed members of the Montana State Legislature in return for their votes. At the time, U.S. senators were chosen by their respective state legislatures. The corruption of his election contributed to the passage of the Seventeenth Amendment. The U.S. Senate refused to seat Clark because of the 1899 bribery scheme, but a later senate campaign was successful, and he served a single term from 1901 until 1907.[6] In responding to criticism of his bribery of the Montana legislature, Clark is reported to have said, "I never bought a man who wasn't for sale."

Clark died at the age of 86 in his New York City mansion. His estate at his death was estimated to be worth $300 million, (equivalent to $4.15 billion in 2023)[8], making him one of the wealthiest Americans ever.[9] [10]

In a 1907 essay, Mark Twain, who was a close friend of Clark's rival, Henry H. Rogers, an organizer of the Amalgamated Copper Mining Company,[11] portrayed Clark as the very embodiment of Gilded Age excess and corruption:

He is as rotten a human being as can be found anywhere under the flag; he is a shame to the American nation, and no one has helped to send him to the Senate who did not know that his proper place was the penitentiary, with a ball and chain on his legs. To my mind he is the most disgusting creature that the republic has produced since Tweed's time.[12]

Senator Clark served a full term without much particular distinction, though he was active as a Senator, particularly in issues that were important to his business, including land use and irrigation.[13]

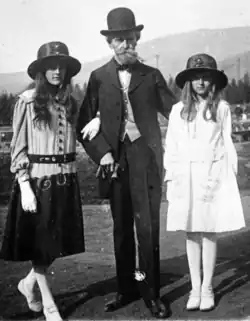

Family

Clark was married twice. His first marriage was to Katherine Louise "Kate" Stauffer in 1869 until her death in 1893.[14][15] Together, they had seven children,[16][17] including Charles Walker Clark and William Andrews Clark Jr.

After Kate's death in 1893, William married his second wife, the woman who had been his teenage ward, Anna Eugenia La Chapelle (March 10, 1878, Michigan – October 11, 1963, New York). They claimed to have been married in 1901 in France. Anna was 23 and William was 62.[18] They had two children:[16][17]

- Louise Amelia Andrée Clark (August 13, 1902, Spain – August 6, 1919, Rangeley, Maine)

- Huguette Marcelle Clark (June 9, 1906, Paris, France – May 24, 2011, New York City)[19]

In early 1946, Anna commissioned the Paganini Quartet, and acquired the four famous Stradivarius instruments once owned by Niccolo Paganini for their use.

Mary Joaquina Clark de Brabant

Clark's firstborn child was born in Helena, Montana in 1870.[20] She married Dr. Everett Mallory Culver in 1891 in New York City, Charles Potter Kling in 1905 in New York City, and Marius de Brabant in 1925 in Los Angeles.[21] Her first marriage produced the only child that survived adulthood, Katherine Calder Culver. Mary had a mansion estate called 'Plaisance' next to the Vanderbilt's at Centerport Long Island, a New York City townhouse on 51st Street, and multiple other estates throughout the country.[22][23] She loved theatrics and music, and was the life of many parties, debutantes, and soirees that she hosted or attended as a prime socialite.[24] Mary was philanthropically minded and among many hundreds of causes, she provided major gifts and endowments to many churches (including St. Thomas in New York City, St. John's Episcopal in Butte, and St. Thomas Episcopal in Clarkdale, Arizona), musical gifts to Carnegie Hall, the Emerald-Hodgson Hospital in Tennessee, the New York Diet Kitchen Association, the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Berry College in Georgia, and the Women's Committee for the Repeal of the 18th Amendment.[25][26][27][28] She died in 1939 and is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in New York.[29]

Clark's firstborn son was born in Deer Lodge, Montana in 1871. He married Katherine Quinn Roberts in 1896, Celia Tobin (heiress of Tobin banking concerns) in 1904, and Elizabeth Wymond Judge in 1925. He had four children in his marriage with Celia Tobin, three daughters and a son. He was known mostly as "Charlie" and served in many substantial capacities for his father's business, political, and personal affairs. He was quite prone to both heavy drinking and gambling.[30] Charlie was also known for reading propensity and his book collecting, with many rare and famous books collected over several decades. He had a mansion in Butte, several estates in California (San Mateo and Pebble Beach among them), as well as property throughout the country.[31][32]

Katherine Louise Clark Morris

Clark's second daughter was born in Helena in 1875. She married Dr. Lewis Rutherfurd Morris in 1900. They had one child, Katherine Elizabeth Morris (married Hall). Catherine and Dr. Morris had a large apartment in New York City, the extensive Morris Manor Farm estate in upstate New York, and a South Carolina Plantation among other property holdings throughout the country. Much like her step-sister Huguette, she tended toward being reclusive particularly after her husband died in 1936. Catherine died at the age of 99, in 1974, and is buried in the Morris family cemetery at the All Saints Chapel Church in Morris, New York.[33][34]

Junior was born in Deer Lodge in 1877. He went on to study earn a degree in law at University of Virginia. He was closely associated with Clark's major business interests in Butte and Arizona. In addition to being a primary funder for the Hollywood Bowl, Junior was founder of the Los Angeles Philharmonic in 1919 and its largest donor for many years. He left his library of rare books and manuscripts to the regents of the University of California, Los Angeles. Today, the William Andrews Clark Memorial Library specializes in English literature and history from 1641 to 1800, materials related to Oscar Wilde and his associates, and fine printing. Clark also provided buildings to the University of Virginia Law School Clark_Hall_(University_of_Virginia) and University of Nevada Reno.[35][36] He had mansions and stables in Butte, Montana, a large cabin retreat property on Salmon Lake in Montana, and his largest mansion and mausoleum in Los Angeles.[37][38] His Los Angeles property spanned more than a city block and included the exquisite library building, a large observatory building, elaborate guest housing, and manicured lawns and gardens.[39]

Huguette (pronounced oo-GETT), born in Paris, France in June 1906, was the youngest child of Clark with his second wife, Anna Eugenia La Chapelle. She married once but divorced less than a year later. She led a reclusive life thereafter, seldom communicating with the public nor with her extended family. For many years, she lived in three combined apartments, with a total of 42 rooms, on New York's Fifth Avenue at 72nd Street, overlooking Central Park. In 1991, she moved out and for the remainder of her life lived in various New York City hospitals.[40]

In February 2010, she became the subject of a series of reports on MSNBC after it was reported that the caretakers of her three residences (including a $24 million estate in Connecticut, a sprawling seaside estate in Santa Barbara, California and her Fifth Avenue apartments valued at $100 million) had not seen her in decades. These articles were the basis for the 2013 bestselling book Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune. by investigative reporter Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell, Jr.

Her final residence was Beth Israel Medical Center, where she died on the morning of May 24, 2011, age 104.[41] Huguette's extraordinary collection of arts and antiquities were consigned to go on the auction block at Christie's in June 2014, over three years after her death.[42]

J. Ross Clark

The youngest brother of Clark, James Ross Clark became an instrumental figure in Clark's empire, particularly in California and Las Vegas but also in Butte and Arizona. J. Ross married Miriam Augusta Evans, who was the sister of the woman who married Clark's rival Marcus Daly. J. Ross had a minor mansion in Butte and a mansion on West Adams in Los Angeles. He was President of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce and held many smaller governmental posts.[43][44]

Joseph Kithcart Clark

Joseph was Clark's nearest in age brother was born in 1842. He helped Clark with stores and mail operations, as well as various mining operations. He was elected to the first legislative session of the State of Montana and served honorably. Joseph had a mansion in Portland.[45][46]

Walter Clark

Clark's nephew, Walter Miller Clark, son of James Ross and Miriam Augusta (Evans) Clark, along with Walter's wife, Virginia (McDowell) Clark, were passengers on the RMS Titanic. They were on their honeymoon. He was among the 1,514 who died on April 15, 1912, after the ship struck an iceberg at 2:20 a.m. Walter's wife, Virginia, was rescued by the RMS Carpathia, and arrived in New York City a widow.

Some of Mr. Clark's personal items were retrieved in the debris field during an expedition to the site of the sinking in 1994. They were identified by engraved initials. They included shaving soap, toiletry items, cuff links, and gambling chips.[47]

Legacy

Clark served twice as President of the Montana Constitutional Convention, ably presiding over efforts to turn the territory toward statehood.[48][49] Clark's extensive art collection was donated to the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C. after his death, greatly enriching that museum's holdings of European as well as American art. The Clark donation also included the construction of a new wing for the Corcoran, known appropriately as the Clark Wing. He left the Columbia Gardens to Butte, and the Paul Clark home to the orphaned children of Butte.[50][51][52] Clark gave the Mary Andrews Clark home in Los Angeles for working women.[53] He provided initial and ongoing endowment funds for the Kindergarten in New York City in honor of his first wife.[54]

Clark further donated 135 acres to the Girl Scouts in honor of his elder daughter (by his second wife), Louise Amelia Andrée (who died at age 16 of meningitis), who had been very happy there. The Girl Scout camp in Briarcliff Manor was named Camp Andree Clark.[55]

Clark County, Nevada

The city of Las Vegas was established as a maintenance stop for Clark's San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad. He subdivided 110 acres (45 ha) into 1200 lots, some of which on the corner of Fremont Street in Las Vegas sold for as much as $1750. The Las Vegas area was organized as Clark County, Nevada, in Clark's honor. Clark's involvement in the founding of Las Vegas is recounted in a decidedly negative light by Chris Romano in the "Las Vegas" episode of Comedy Central's Drunk History, with Rich Fulcher portraying Clark.

Clarkdale, Arizona

Clarkdale, Arizona, named for Clark, was the site of smelting operations for Clark's mines in nearby Jerome, Arizona. The town includes the historic Clark Mansion, which sustained severe fire damage on June 25, 2010. Clarkdale is home to the Verde Canyon Railroad wilderness train ride which follows the historic route that Clark had constructed in 1911 and home to the Copper Art Museum.[56] Nearby Jerome had hospital and many other buildings built by Clark.[57]

Clark's namesake son also provided the William Andrews Clark Library complex to UCLA in his father's honor and name.[58]

Mansions

Between 1884 and 1888, Clark constructed his first mansion, a 34-room, Tiffany-decorated home on West Granite Street, incorporating the most modern inventions available, in Butte, Montana. This home is now the Copper King Mansion bed-and-breakfast, as well as a museum.[59] In 1899, Clark vastly improved upon Columbia Gardens (amusement park) for the children of Butte. It included flower gardens and greenhouses, a dance pavilion, an amusement park, a zoo, a lake, and picnic areas. An evening scene between characters Arline Simms (played by Anne Francis) and Buz Murdock (played by George Maharis) from the Route 66 television series 1961 episode "A Month of Sundays" was shot on location at Columbia Gardens where she emotionally falls into his arms on the grand staircase.

In 1899, Clark bought the famous Stewart's Castle in Washington, D.C., intending to build a larger mansion on the land.[60] He razed the building while living next door at 1915 Massachusetts Avenue NW while he was a U.S. Senator. He never completed his planned D.C. mansion, and sold the property in 1921.[61]

Like many Clark family members, Senior Clark also had his own custom built private railcar, completed toward the end of 1905. Dubbed "the Palace on Wheels" the special Pullman car was 82 feet long with frescoed ceilings, plush carpeted floors, and built of steel to be "wreck proof." It contained a kitchen, pantry, formal dining room that could seat twelve, 1500-year-old carved wood, his (in vermillion) and hers (in oak) sleeping apartments, tiled bathing room, an office, servant's sleeping quarters, a trunk room and closets, and an observation compartment. It was electrified, had its own speedometer so Clark could calculate time of arrival himself, and had a Pintsch gas system. W.A.C. was emblazoned on the sides.[62][63]

To keep up with his contemporaries--the Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, Astors, Fricks, and Carnegies--Clark built a much larger and more extravagant 121-room mansion on Fifth Avenue in New York City, the William A. Clark House. His plans grew in scope significantly from the time he purchased the land in 1895 until its ultimate completion in 1911. To provision the extensive materials needed for this excessive structure, Clark bought an entire stone quarry in Maine and a bronze factory in New York among other company acquisitions. This truly fantastic mega-mansion across from Central Park featured an enormous tower rising above the street 163 feet, fifth floor ballrooms, five art gallery rooms full of mostly European paintings with most of these rooms multi-storied with skylights and one of them a full 95 feet long, several library rooms, Turkish bath and spa rooms, a wine cellar, interior driveway with garage and carport, 26 guest suites and rooms, 31 white marble bathrooms (many with ceilings of Faience marble), a free-standing circular Maryland marble staircase with extensive bronze and gold plate railing and ornamentation, two-story stone caryatids, a 36-foot marble rotunda with a dome of colored mosaics leading into 30-foot conservatory room which showcasing enormous glass panels ensconced in two-story bronze supports, a Tennessee marble fountain with carved marble mermaids, a theater stage with hydraulic lifts, a large elevator that could fit 20 people, a main dining room accentuated with a 15-foot Numidian marble fireplace held up by life-sized carved figures of Diana and Neptune and further accentuated with quarter-sawn oaks imported directly from the Sherwood Forest, the world's largest private organ, and even multiple quarantine rooms in case of a pandemic. A fireplace from a 16th Century Normandy castle, stained-glass panels from a French 13th Century Cathedral, and the famous Salon Dore an 18th Century French period room were brought form Europe and placed in the home among dozens of other imported pieces. Clark packed so much art into the home that when it the art was donated to the Corcoran Museum (after the Metropolitan Museum of Art declined the bequest) through his will, the family had to create an entire museum multi-story wing just to display portions of the collection.[64] Seven tons of coal was brought in daily to keep the mansion operations going, brought in on Clark's own private rail line to the home.[65][66]

In Santa Barbara in 1923, Clark bought the William Miller Graham mansion on a 23-acre estate with stunning views and beachfront on the Pacific Ocean. This mansion was razed and his widow Anna built her own mansion on the property in the early 1930s, now the home of Bellosguardo Foundation.[67]

The Montana Hotel in Jerome, Arizona was built by Clark's United Verde Copper Company and housed suites for him and his family.[68] In current times, there are many dozens of mansions and buildings associated with Clark and his family in most U.S. states, including Arizona[69][70], California Bellosguardo Foundation Mary Andrews Clark Memorial Home, Connecticut[71], Florida, Maine[72], Massachusetts[73],Montana[74][75], New Jersey[76], New York William A. Clark House, Oregon[77] and South Carolina [78], and Paris, France[79].

See also

- Andree Clark Bird Refuge, Santa Barbara, California

- Atlantic Cable Quartz Lode

- List of historic properties in Clarkdale, Arizona

- Mary Andrews Clark Memorial Home – a landmark Los Angeles home for women built by Clark as a memorial for his mother

Notes

- ^ "Copper King William A. Clark". Copper King Mansion. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 31, 2011.

- ^ Klepper, Michael; Gunther, Michael (1996), The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates—A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present, Secaucus, New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group, p. xiii, ISBN 978-0-8065-1800-8, OCLC 33818143

- ^ Dedman, Bill (2013). Empty Mansions (Paperback ed.). New York: Ballantine Books. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-345-53453-8.

- ^ Bill Dedman, Paul Clark Newell, Jr., Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Loss of one of the World's Greatest Fortunes, London: Atlantic Books, 2013, p. 30

- ^ "EX-SENATOR CLARK, PIONEER IN COPPER, DIES OF PNEUMONIA; Taken with a Cold a Few Days Ago, He Succumbs Suddenly Here at 86. FAMILY AT HIS BEDSIDE He Had Been Actively Directing His Business Affairs Until He Became Ill. HIS CAREER PICTURESQUE Went to Montana with Ox Team and Acquired One of Biggest Fortunes in America. EX-SENATOR CLARK DIES OF PNEUMONIA (Published 1925)". The New York Times. March 3, 1925.

- ^ a b "S. Doc. 58-1 - Fifty-eighth Congress. (Extraordinary session -- beginning November 9, 1903.) Official Congressional Directory for the use of the United States Congress. Compiled under the direction of the Joint Committee on Printing by A.J. Halford. Special edition. Corrections made to November 5, 1903". GovInfo.gov. U.S. Government Printing Office. November 9, 1903. p. 66. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ "Bioguide Search".

- ^ Johnston, Louis; Williamson, Samuel H. (2023). "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved November 30, 2023. United States Gross Domestic Product deflator figures follow the MeasuringWorth series.

- ^ Matt Schudel, Huguette Clark, copper heiress and recluse, dies at 104, The Washington Post, May 24, 2011; retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ Pitts, Stanley Thomas (May 2006). An Unjust Legacy: A Critical Study of the Political Campaigns of William Andrews Clark, 1888-1901 (PDF). University of North Texas: M.S. thesis. p. 205. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ Dias, Elias (1984). Mark Twain and Henry Huttleston Rogers: An Odd Couple. Fairhaven, Massachusetts: Millicent Library. LCCN 84062878.

- ^ "Senator Clark of Montana." In Mark Twain in Eruption, ed Bernard DeVoto, 1940.

- ^ "National Irrigation Congress at Ogden," New York Times, July 26, 1903

- ^ "Daughter of Connellsville's controversial billionaire dies". The Tribune-Review. May 28, 2011. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Hopkins, A.D. (February 7, 1999). "William Andrews Clark (1839-1925): Montana Midas". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on November 17, 1999. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ a b Bill Dedman; Paul Clark Newell, Jr. (2013). Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 9780345545565. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ a b "The Family of W. A. Clark" (PDF). Penguin Random House. Retrieved January 26, 2022.

- ^ "At 104, mysterious heiress is alone now - Business - Local business - Huguette Clark mystery - NBC News". NBC News. August 19, 2010.

- ^ Dedman, Bill (May 24, 2011), Huguette Clark, the reclusive copper heiress, dies at 104, MSNBC, archived from the original on January 1, 2012, retrieved May 24, 2011

- ^ "Mary Joaquina Clark DeBrabant (1870-1939) - Find". Find a Grave.

- ^ https://www.seekingmyroots.com/members/files/G001328.pdf

- ^ "DE BRABANT ESTATE IN CENTERPORT SLD; New Owners Found for Three Houses in the Rockaways (Published 1943)". The New York Times. February 16, 1943.

- ^ "Palm Springs Architecture".

- ^ "DEBUTANTE DANCE FOR LUCILE THIERIOT; MRS. Marius de Brabant Hostess to a Large Company at Her Home in This City. YOUNG PEOPLE ARE GUESTS Miss Thieriot Introduced to Society in Autumn by Her Parents at Long Island Home. (Published 1932)". The New York Times. January 10, 1932.

- ^ https://saintthomaschurch.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/The-2022-Yearbook-for-Saint-Thomas-Church-Fifth-Avenue.pdf

- ^ "History".

- ^ "OMNIA - Berry College. Library".

- ^ "MRS. M. DE BRABANT; Daughter of Late U.S. Senator Clark of Montana Dies (Published 1939)". The New York Times. December 20, 1939.

- ^ "Mary Joaquina Clark DeBrabant (1870-1939) - Find". Find a Grave.

- ^ Bill Dedman, Paul Clark Newell, Jr., Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Loss of one of the World's Greatest Fortunes, London: Atlantic Books, 2013, p. 142

- ^ "Charles Walker "Charlie" Clark (1871-1933) - Find". Find a Grave.

- ^ https://www.seekingmyroots.com/members/files/G001328.pdf

- ^ "Katherine Stauffer Clark Morris (1875-1974) -". Find a Grave.

- ^ https://www.seekingmyroots.com/members/files/G001328.pdf

- ^ "Clark Hall Named to Virginia Landmarks Registry | UVA Today". July 11, 2008.

- ^ "Clark Administration Building - Opened as the Alice McManus Clark Library in 1927".

- ^ "Salmon Lake".

- ^ "W.A. Clark Jr. Carriage House - Butte National Historic Landmark District".

- ^ "Adams Boulevard".

- ^ Dedman, Bill (2013). Empty mansions : the mysterious life of Huguette Clark and the spending of a great American fortune (First ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0345534521.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Fanelli, James (September 7, 2010), "Huguette Clark's lawyer fires back at relatives who want him ousted", New York Daily News, retrieved September 8, 2010

- ^ "Eccentric Heiress's Untouched Treasures Head For The Auction Block", National Public Radio, Margot Adler, June 17, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- ^ "J. Ross Clark".

- ^ https://www.google.com/search?q=J.+Ross+Clark+biography&oq=J.+Ross+Clark+biography&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOTIHCAEQIRigATIHCAIQIRigATIHCAMQIRigAdIBCDI4MDdqMGo0qAIAsAIA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

- ^ http://files.usgwarchives.net/mt/silverbow/bios/clarkjoseph.txt

- ^ "Joseph Kithcart Clark (1841-1903) - Find a Grave". Find a Grave.

- ^ Gillan, Jeff (April 10, 2017). "Titanic sank 105 years ago this Saturday, taking a piece of Las Vegas with it".

- ^ "Montana Constitutional Convention (1884) Records - Archives West".

- ^ https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=&httpsredir=1&article=4266&context=etd

- ^ "Columbia Gardens".

- ^ "Butte, America's Story Episode 293 - Paul Clark Home".

- ^ "Paul Clark Home - Butte National Historic Landmark District".

- ^ ""To Exalt the Standard of Womanhood": A Photo of the Mary Andrews Clark Memorial Home for Working Women, Los Angeles, 1910s". March 23, 2021.

- ^ https://www.seekingmyroots.com/members/files/G001328.pdf

- ^ "Camp Andree Clark". Archived from the original on May 28, 2011. Retrieved December 23, 2013.

- ^ Peterson, Hellen Palmer (May 2008). Landscapes of Capital: Culture in an Industrial Western Company Town, Clarkdale, Arizona, 1914-1929. Northern Arizona University: Ph.D. dissertation. p. 214. ISBN 9780549679448. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ^ "Chief Surgeon's House and First United Verde Hospital". September 6, 2018.

- ^ https://clarklibrary.ucla.edu/

- ^ Tribune Staff. "125 Montana Newsmakers: The Copper Kings". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ^ Hansen, Stephen A. (2014). A History of Dupont Circle: Center of High Society in the Capital. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. pp. 31–44, 59, 146–148. ISBN 9781625850843.

- ^ "Stewart Castle Site Purchased". Evening Star. December 17, 1921. Archived from the original on February 7, 2017. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ "Chicago Great Western 99".

- ^ "Railway Preservation News • View topic - Private Car of Walter a. Clarke".

- ^ "History | Corcoran School of the Arts & Design | Columbian College of Arts & Sciences | the George Washington University".

- ^ The Pittsburgh Press. (1910). How Would You Like to Manage This Great House? Mar 17, 1910, pg. 14.

- ^ "William A. Clark Mansion".

- ^ "The Other House at Bellosguardo". October 30, 2014.

- ^ "History of Jerome - One of the best hotel in Arizona".

- ^ "Chief Surgeon's House and First United Verde Hospital". September 6, 2018.

- ^ "Residence for Mr. C.W. Clark (William Clark III), United Verde Copper Company Owner".

- ^ "New Canaan Now & then: 'Le Beau Chateau' (The Huguette Clark Estate)". December 26, 2024.

- ^ "Briarcliff Manor and the Girl Scouts Movement, Part 2: Camp Andrée - Notebook 2025-2".

- ^ https://constructberkshires.org/wp-content/uploads/2410581.pdf

- ^ "Butte, America's Story Episode 293 - Paul Clark Home".

- ^ "Tour began in 1915 Mowitza Lodge and ended in present".

- ^ "Copper in the Arts: Issue #109".

- ^ "JOSEPH K. CLARK DEAD.; Brother of United States Senator Clark Stricken with Brain Trouble at Los Angeles, Cal. (Published 1903)". The New York Times. January 26, 1903.

- ^ "Pleasant Hill Plantation - Garnett, Hampton County, South Carolina SC".

- ^ "Early days in France". February 7, 2023.

Sources

- Dedman, Bill; Newell, Paul Clark Jr. (2013), Empty Mansions: The Mysterious Life of Huguette Clark and the Spending of a Great American Fortune, New York: Ballantine Books, ISBN 978-0-345-53452-1

- NBCNews.com: Huguette Clark, the reclusive heiress, and the men managing her money, an NBCNews.com special report

- United States Congress. "William A. Clark (id: C000454)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Hopkins, A.D.; Evans, K.J. (2000), The First 100, Las Vegas: Huntington Press, ISBN 0-929712-67-6

- Mangam, William (1941), The Clarks An American Phenomenon, New York, NY: Silver Bow Press, OCLC 390214