West Pomeranian Lake Land

The West Pomeranian Lake Land is the northern part of the South Baltic Lake Lands, characterized by its lake-rich landscape. Covering an area of 9,700 km², it accounts for approximately 3.1% of Poland's administrative territory. The region features a series of terminal moraines formed during the Pomeranian phase of the Weichselian glaciation, with Siemierzycka Góra in the Bytów Lake Land as its highest point at 256.5 m above sea level. Soils in the macroregion primarily developed from glacial deposits – clays, sands, gravels, and silt from meltwater. Predominant soil types include brown earth, podzolic soils, and podzols, with hydric soils characteristic of the region. The area boasts a well-developed river network, including major coastal rivers such as the Rega, Parsęta, and Słupia, and the sandur plains of the South Pomeranian Lake Land with rivers like the Brda, Drawa, and Gwda. The region has a high lake density, exceeding 10% in some mesoregions. The largest lake, Drawsko Lake, a multi-channel lake, spans 19.6 km² with a maximum depth of 79.7 m. Most lakes in the lake land are classified as eutrophic based on their trophic state. The macroregion is underlain by substantial groundwater reserves, while soil water is of marginal importance due to its limited volume and poor quality. The climate is strongly influenced by the Baltic Sea, resulting in milder winters and cooler summers compared to most of Poland. According to Poland's climatic regionalization, the West Pomeranian Lake Land encompasses three climatic zones: the West Pomeranian Region in the west, the Central Pomeranian Region in the center, and the East Pomeranian Region in the east.

The flora is dominated by Central European vascular plants. Forest habitats include fresh mixed forest, fresh mixed coniferous forest, and fresh forest. Fertile beech forest and mixed coniferous forests are prominent in terms of potential natural vegetation. Some plant species in the region are glacial relicts from the Ice Age. The fauna is primarily composed of species typical of the North European Plain, with a migratory character.

Location

According to Jerzy Kondracki's physico-geographical regionalization of Poland, the West Pomeranian Lake Land forms the northern part of the South Baltic Lake Lands subprovince (314–316).[1] It features a series of terminal moraines from the Pomeranian phase of the Weichselian glaciation.[2]

The macroregion is separated from the sea by the Szczecin Coast (313.2/3) and Koszalin Coast (313.4).[3] It borders the East Pomeranian Lake Land (314.5) to the east, the South Pomeranian Lake Land (314.6/7) to the south, the Lower Oder Valley (313.24) to the west, and briefly the Toruń-Eberswalde Urstromtal (315.3).[3]

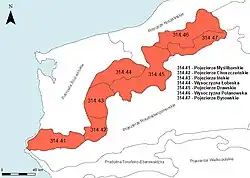

Spanning 9,700 km², it constitutes about 3.1% of Poland's administrative area and 12.6% of the subprovince.[2][4] The macroregion is divided into seven mesoregions: Myślibórz Lake Land, Choszczno Lake Land, Ińsko Lake Land, Łobez Upland, Drawsko Lake Land, Polanów Upland, and Bytów Lake Land.[2] Administratively, it lies within the West Pomeranian Voivodeship and Pomeranian Voivodeship.[5]

Geological structure and landforms

.jpg)

The West Pomeranian Lake Land is geomorphologically distinct from other Pomeranian lake lands within the South Baltic Lake Lands subprovince, though all share a lake-rich landscape. The primary landforms are linked to the retreat of the last glaciation during the Pomeranian phase.[6] As the ice sheet retreated, it deposited northern-origin materials – gravels, sands, clays, and boulders. During the Pomeranian stage, around 10,000–12,000 years ago at the end of the Pleistocene, a series of terminal moraines formed,[2][7] distinguishing the West Pomeranian Lake Land among the subprovince's macroregions.[2][8] Multiple ice margin lines are evident in some areas, such as the Myślibórz, Chojna, and Mielęcin lines in the Myślibórz Lake Land.[6]

The terminal moraine belt varies in thickness, exceeding 200 m in the Bytów Lakeland. These moraines consist of stony till.[7] In the western part, from the Myślibórz to Drawsko lake lands, the material is rich in calcium compounds, while in the eastern Bytów Lake Land, calcium content is low, significantly influencing ecological and lake diversity.[7]

The moraine belt stretches linearly from southwest to northeast, roughly parallel to the Baltic Sea coastline. In the west, the layout is latitudinal in the Myślibórz Lake Land and meridional in the Choszczno Lake Land.[6] Elevations increase northeastward.[2][7] Western elevations range from 100 to 150 m above sea level, with Zwierzyniec (166.8 m) in the Myślibórz Lake Land and Głowacz (179.7 m)[9] in the Ińsko Lake Land as high points.[2] In the central Drawsko Lake Land, Wola Góra reaches 219.2 m,[9] while Siemierzycka Góra (256.5 m)[10] in the Bytów Lake Land is the highest.[7]

Other marginal zone features from the Pomeranian phase include two arcs of elevations encircling the Bay of Pomerania and Gdańsk Bay depressions.[2] All mesoregions are classified as young glacial uplands, typically with lakes.[3]

During the ongoing Holocene, initial landforms have undergone significant changes due to climate shifts and vegetation development. Lakes formed where ice blocks melted, and a new hydrographic network emerged.[7] Denudation processes have softened and lowered Pleistocene landforms, while eroded material contributed to alluvial and deluvial processes. Human activity also shapes the original landscape.[7]

Soils

Soils in the West Pomeranian Lake Land primarily formed from glacial deposits – clays, sands, gravels, and meltwater silt. In river valleys, parent material consists mainly of Holocene deposits – alluvium, peat, and gyttja.[11] This diversity results in varied physical and chemical soil properties. Brown earth, podzolic soils, and podzols dominate, with hydric soils – formed under high moisture with bog vegetation – being characteristic.[11]

Brown earth, typically formed from till, occur in deciduous forest habitats with near-neutral soil pH. They have good biochemical properties and are classified as II and III soil quality class.[11] Podzolic soils form from decalcified till under acidic to slightly acidic conditions, offering favorable water-air conditions and ranking as III and IV class.[11] Podzols develop from loose and weakly loamy sands, classified as IV and V class.[11]

Hydrology

.jpg)

River network

The West Pomeranian Lake L\and has a dense river network closely tied to its glacial landscape. The terminal moraine belt serves as a watershed. Northward, rivers flow toward the Baltic Sea or the lower Oder river, while southward rivers drain toward the Toruń-Eberswalde Urstromtal.[2][12] Major rivers flowing directly to the Baltic include the Rega (168 km), Słupia (139 km), and Parsęta (127 km), with steep gradients, especially in upper reaches, up to 5‰. Southern rivers, with short headwater sections, include the Brda (238 km), Gwda (145 km), and Drawa (186 km). The Drawa flows through Drawsko and Lubie Lakes in the Drawsko Lake Land, while the Gwda and Brda originate in the Bytów Lake Land.[12][13]

Lakes

The region's high lake density is a legacy of the Weichselian glaciation. In the Drawsko, Ińsko, and western Bytów Lake Lands, lakes cover over 10% of the surface.[14] Most are ribbon or kettle types.[2] The largest include Drawsko (a multi-ribbon lake, 17.8 km², 79.7 m deep), Wielimie (a moraine-dammed lake, 18.6 km², 5.5 m deep), and Lubie (a ribbon lake, 14.7 km², 46.2 m deep) in the Drawsko Lake Land.[13] The Myślibórz Lake Land has around 200 lakes over 1 ha, with Myśliborskie Lake (6 km², ~22 m deep) as the largest.[15] The Choszczno Lake Land has fewer, mostly channel lakes, led by Pełcz Lake (2.7 km², 31 m deep).[16][17] The Ińsko Lake Land has significant lake coverage, with Woświn Lake (8 km², 28 m deep) as the largest.[17] The Łobez Upland has small, less numerous lakes.[18] The Polanów Upland has few lakes,[19] mostly in its eastern part,[20] with Jasień Lake (5.8 km², 32 m deep) as the largest.[19] The Bytów Lake Land has many small lakes,[19] often kettle lakes in various stages of peat formation,[14] with Bobięcińskie Wielkie Lake (5 km², 48 m deep)[19][21] as the largest and deepest lobelia lake in Poland.[22]

In terms of trophic status, most lakes in the macroregion are classified as eutrophic. They are characterized by a high concentration of nutrients dissolved in the water and abundant vegetation.[14] Agriculture has played a fundamental role in this process. In many areas, the transformation of the original forest landscape into an agricultural one contributed to the disruption of water relations by reducing the soil's retention capacity and facilitating surface runoff. This, in turn, led to a significant influx of nutrients into surface waters.[23] In the Drawsko and Bytów lake lands, oligotrophic lakes are commonly found. These are characterized by low nutrient levels and good oxygen conditions, and they are generally deep lakes.[14] Among oligotrophic lakes, one can distinguish between non-calcareous (lobelian) lakes – typical of the eastern part of the macroregion, where the morainic material lacks calcium compounds – and calcareous lakes, characteristic of the western part of the lake land, where the morainic material contains large amounts of calcium compounds. Calcareous oligotrophic lakes occur most frequently in the Myślibórz Lake Land, while non-calcareous ones are most common in the Bytów Lake Land (the highest concentration in Poland).[24] In the eastern part of the West Pomeranian Lake Land, dystrophic lakes are also well represented. These lakes have acidic, brown-colored waters due to humic substances.[14]

Groundwater

The macroregion has substantial groundwater reserves, with depth determined by substrate structure and terrain. In lakelands, groundwater is found as shallow as 10 m, deeper in uplands. It supports the river network and is used economically due to its purity.[25] Groundwater outflows as small lakes or springs are common in the moraine belt, fostering spring fen formation. Soil water is less significant due to low volume and poor quality.[25]

Water quality

Four reference lakes – Jasień Południowy, Jasień Północny, Morzycko, and Wielkie Dąbie Lake – monitor surface water trends. In 2012, all had good chemical status of waters.[26] However, their ecological status of waters varied, generally moderate, with Morzycko occasionally poor and both Jasień lakes declining from very good to good or moderate between 2010 and 2013.[26] In the early 1980s, both Jasień lakes failed water quality classes in Poland due to excessive copper levels.[27] Morzycko, assessed in the mid-1970s and late 1990s, was rated Class II despite some parameter exceedances.[28]

Climate

The climate is heavily influenced by the Baltic Sea, leading to milder winters and cooler summers than most of Poland. Variations within the macroregion are tied to hypsometry.[29] Annual temperatures decrease eastward with rising elevation. Precipitation distribution depends on terrain and proximity to moisture-laden northwest oceanic air. The northern moraine slopes receive higher rainfall than the southern side. The region has high relative humidity, averaging 81% annually, with prevailing westerly winds.[2][29]

Per Alojzy Woś's climatic regionalization, the West Pomeranian Lake Land includes three zones: West Pomeranian, Central Pomeranian, and East Pomeranian.[30][31] The West Pomeranian Region has frequent frost days with moderate cold (daily average 0.0 °C to -5.0 °C, max above 0 °C, min at or below 0 °C) and low cloud cover (≤20%), surpassed only by the Carpathian Mountains. It sees fewer days (10 annually) of frost with high cloud cover (≥80%) and precipitation (≥0.1 mm). Moderately frosty days (daily average 0.0 °C to -5.0 °C, both max and min at or below 0 °C) are rare (7 annually).[31] The Central Pomeranian Region has more days of moderately warm weather (daily average 5.1 °C to 15.0 °C, both max and min above 0 °C) with high cloud cover (50 days annually) and cool, rainy weather (daily average 0.1 °C to 5.0 °C, 26 days annually).[31] The East Pomeranian Region has the highest national count of very cool frost days (daily average 0.1 °C to 5.0 °C, max above 0 °C, min at or below 0 °C) with high cloud cover and moderately frosty, cloudy days (21–79% cloud cover) with precipitation, but few very warm, rainy days (daily average 15.1 °C to 25.0 °C).[31][32]

Flora

Overview

Vegetation began recovering post-glaciation with treeless tundra and shrubs. As the Pleistocene ended, warming allowed trees like downy birch and steppe vegetation to develop. The preboreal Holocene saw pine-birch forests, later joined by elm, alder, and ash. The warm, humid boreal period added hazel, followed by linden and oak. Oak forests, alder carr, and riparian forest thrived in the Atlantic period.[33] The drier subboreal period saw beech expansion and reduced elm and linden. The modern forest landscape was shaped by cooling and moistening in the subatlantic period, alongside settlement and widespread deforestation.[33] Some plants are Ice Age glacial relicts, thriving in peatlands like bogs and swamp forests, including Dicranum undulatum, Carex heleonastes, creeping sedge, alpine bulrush, Chamaedaphne calyculata, crowberry, Vaccinium microcarpum, and moss-sedge communities in acidic fens with fleshy starwort, Jacob's-ladder and shrubby birch. Peat lakes preserve floating bur-reed and least water-lily.[33]

Forest habitat types

Per Poland's natural-forest regionalization, the West Pomeranian Lake Land lies within the Baltic Region, aligning with the Pomeranian phase's extent.[34] Dominant forest habitats are fresh mixed forest, fresh mixed coniferous forest, and fresh forest.[35] The southwest favors fresh mixed and fresh forests, while the northeast has more fresh and mixed coniferous forests. The Bytów Lake Land has one of Poland's highest shares of swamp mixed coniferous forest in State Forests land, and the Drawsko Lake Land has a high share of swamp mixed forest compared to western Poland.[36]

Forest communities

Potential natural vegetation is dominated by fertile beech forest, especially in the Myślibórz, Ińsko, and Choszczno lake lands, and mixed coniferous forests in the Drawsko Lake Land and Łobez Upland.[37] The Polanów Upland and Bytów Lake Land have no dominant community, featuring acidic beech forest, fertile beech forests, and mixed and pine forests.[37]

Vascular plants

Central European vascular plants dominate, including forest-forming trees like European hornbeam, pedunculate oak, sessile oak, Norway maple, ash, and European beech, and groundcover plants like wood anemone and dog's mercury. Outside forests, cowslip grows on dry, sandy soils, marsh pennywort on meadows, and white waterlily in waters. The Myślibórz Lake Land has calcium-loving flora on lake chalk deposits,[38] with chalk peatlands among Poland's main northwestern sites.[39] Arctic-alpine and boreal elements, like white adder's mouth, common butterwort, great horsetail, Valeriana sambucifolia, and wild garlic, are common in the Bytów and Drawsko lake lands. Oceanic species include cross-leaved heath, swamp sawgrass, brown beaksedge, blunt-flowered rush, and Groenlandia densa.[40]

Fauna

Overview

The fauna is migratory, shaped by post-glacial settlement, primarily consisting of North European Plain species, supplemented by western and eastern European, Atlantic, and rare southern and northern species.[41] The region is zoogeographically transitional, evidenced by the presence of common nightingale (western) and thrush nightingale (eastern). Invasive species like the spinycheek crayfish negatively impact native European crayfish populations.[41][42]

Fish

All lake fishery types per the Inland Fisheries Institute are present: vendace, bream, zander, tench-pike, and crucian carp lakes. Vendace lakes, typically deep with high clarity and oxygen, include species like vendace, lavaret, European smelt, common bleak, common bream, common roach, European perch, white bream, Eurasian ruffe, and northern pike. Examples include Drawsko Lake and Ińsko Lake.[43] Bream lakes, up to 20 m deep with limited clarity and abundant underwater vegetation, feature bream, pike, perch, tench, European eel, roach, common rudd, and crucian carp, like Krzemień Lake in the Ińsko Lake Land. Zander lakes, shallow with low clarity, include zander, bream, eel, perch, tench, pike, roach, and ruffe. Tench-pike lakes, shallow and vegetated, host tench, pike, roach, crucian carp, and rarely common carp. Crucian carp lakes are dominated by crucian carp.[43] Valuable species include Atlantic salmon and sea trout. Salmon, once abundant in the Drawa and coastal rivers, is now reintroduced, with the last spawners noted in the Drawa in 1985. Sea trout in the Słupia river show distinct genetic traits, disrupted by improper stocking.[44][45]

Amphibians

.jpg)

Common amphibians include green frogs – edible frog,[46] pool frog,[47] marsh frog[48] – and brown frogs – moor frog[49] and common frog.[50] True toads – common toad,[51] European green toad,[52] and the rarer natterjack toad – are also prevalent.[53] Unique species include the steppe relict common spadefoot,[54] European fire-bellied toad, and European tree frog, which lives in trees outside breeding.[55] Smooth newt[56] and northern crested newt are also present.[57] Seven species – natterjack toad, European green toad, European fire-bellied toad, common spadefoot, European tree frog, moor frog, and smooth newt – are under strict protection in Poland; others have partial protection.[58]

Reptiles

Reptiles are few, including adder, grass snake, common slow worm, sand lizard, and viviparous lizard.[55] The European pond turtle has been reported near Recz, Choszczno, and Myślibórz.[59] The invasive pond slider is noted east of Szczecinek.[60] The European pond turtle is strictly protected; others have partial protection.[58]

Birds

The region's diverse habitats support numerous bird species, especially in wetlands, hosting mallard, Eurasian teal, common pochard, mute swan, and black-headed gull. Others include common tern, great cormorant, grey heron, common gull, black tern, and common crane. Reedbeds shelter the Eurasian bittern (notably abundant in the west),[61] common reed warbler, water rail, and savi's warbler. Sedge and grassy wetlands host common snipe and corn crake, frequented by white stork.[62] In the 1980s, hen harrier pairs nested near Niezabyszewo and between Mielno and Bytów, a declining species.[63] Dry meadows and fields host Eurasian skylark, yellowhammer, and crested lark. Deciduous forests support Eurasian jay, Eurasian chaffinch, European greenfinch, wood warbler, and lesser spotted woodpecker.[62] Forest edges near open areas suit the near-threatened red kite, abundant in Western Pomerania.[64] Coniferous and mixed forests host goldcrest, coal tit, woodlark, and European nightjar,[62] with lesser spotted eagle breeding near wetlands, especially in the Myślibórz and Drawsko lake lands.[65] The white-tailed eagle is numerous in the Myślibórz Lake Land.[66]

Mammals

Mammals include Artiodactyls (red deer, roe deer, wild boar), carnivores (red fox, least weasel, European polecat, European pine marten, beech marten, stoat, European badger), rodents (murids, red squirrel), lagomorphs (European hare, European rabbit), bats (common pipistrelle, greater mouse-eared bat, brown long-eared bat), and insectivores (European hedgehog, European mole, common shrew, Eurasian pygmy shrew, Eurasian water shrew).[67] The rare, relict Iberian water shrew was noted before 1990 in isolated populations.[68]

Nature conservation

As of 2017, the macroregion includes, wholly or partially, landscape parks: Cedynia Landscape Park (small northeastern part in Myślibórz Lake Land),[38] Barlinek-Gorzów Landscape Park (northern part on the Myślibórz-Choszczno border),[15] Ińsko Landscape Park (Ińsko Lake Land),[17] Drawsko Landscape Park (Drawsko Lake Land),[69] and Słupia Valley Landscape Park (mostly in Polanów Upland).[19]

All nature reserve types, except halophyte reserves, exist (as of 2017). These include forest reserves (Olszyny Ostrowskie in Myślibórz Lake Land,[15] Bukowa Góra nad Pysznem in Bytów Lake Land,[19] Dęby Wilczkowskie in Drawsko Lake Land),[69] landscape reserves (Długogóry in Myślibórz Lake Land,[15] Kamienna Buczyna in Ińsko Lake Land,[17] Five Lakes Valley Nature Reserve in Drawsko Lake Land),[69] floristic reserves (Tchórzyno in Myślibórz Lake Land,[15] Mszar nad jeziorem Piaski in Łobez Upland,[70] Wieleń in Polanów Upland,[19] Jezioro Piekiełko in Bytów Lake Land),[19] peatland reserves (Torfowisko nad Jeziorem Morzysław Mały in Drawsko Lake Land,[69] Mszar koło Starej Dobrzycy in Łobez Upland),[70] water reserves (Jezioro Iłowatka in Bytów Lake Land,[19] Jezioro Czarnówek in Drawsko Lake Land),[69] steppe reserves (Wrzosowiska Cedyńskie in Myślibórz Lake Land),[15] and inanimate nature reserves (Brunatna Gleba in Drawsko Lake Land).[71]

The region hosts Special Protection Areas (Słupia Valley SPA, Drawska SPA, Ińsko SPA, Cedyńska SPA, Witnicko-Dębniańska SPA) and Sites of Community Importance under Natura 2000, including Słupia Valley SCI, Wieprza and Studnica Valley, Radew, Chociel and Chotla Valley, Grabowa Valley, Parsęta Basin, Rega Basin, Ina Valley near Recz, Ińsko Lake Land SCI, and Myślibórz Lake Land SCI.[72][73]

References

- ^ Kondracki (2014, p. 35)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kondracki (2014, pp. 68–70)

- ^ a b c Kondracki, Jerzy; Richling, Andrzej (1994). Regiony fizycznogeograficzne, skala 1:1 500 000 [Physico-Geographical Regions, Scale 1:1,500,000] (in Polish). Warsaw: Główny Geodeta Kraju.

- ^ Kondracki (2014, p. 37)

- ^ "Centralna Baza Danych Geologicznych" [Central Geological Database]. Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2017-01-18.

- ^ a b c Kondracki, Jerzy (1994). Geografia Polski. Mezoregiony fizyczno-geograficzne [Geography of Poland: Physico-geographical Mesoregions] (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. ISBN 83-01-11422-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 7–12)

- ^ Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 5–6)

- ^ a b Wojskowa Mapa Topograficzna, skala 1:50 000 [Military Topographic Map, Scale 1:50,000] (in Polish). Sztab Generalny Wojska Polskiego. 1988.

- ^ Wojskowa Mapa Topograficzna, skala 1:50 000 [Military Topographic Map, Scale 1:50,000] (in Polish). Sztab Generalny Wojska Polskiego. 1987.

- ^ a b c d e Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 13–15)

- ^ a b Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 15–17)

- ^ a b Mizerski, Witold; Żukowski, Jan (2008). Tablice geograficzne [Geographical Tables] (in Polish). Warsaw: Adamantan. pp. 157, 172. ISBN 978-83-7350-121-8.

- ^ a b c d e Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 17–19)

- ^ a b c d e f Kondracki (2014, p. 70)

- ^ Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 155–156)

- ^ a b c d Kondracki (2014, p. 71)

- ^ Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, p. 183)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kondracki (2014, p. 73)

- ^ Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 202–203)

- ^ Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 194–195)

- ^ Piasecki, Adam; Krąż, Paweł (2015). Współczesne problemy i kierunki badawcze w geografii [Current Problems and Research Directions in Geography] (PDF) (in Polish). Vol. 3. Kraków: IGIGP UJ. p. 199. ISBN 978-83-64089-15-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-14.

- ^ Kubiak, Jacek; Tórz, Agnieszka (2005). "Eutrofizacja. Podstawowe problemy ochrony wód jeziornych na Pomorzu Zachodnim" [Eutrophication: Key Issues in Protecting Lake Waters in Western Pomerania]. Słupskie Prace Biologiczne (in Polish). 2: 21. ISSN 1734-0926.

- ^ Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 45–60)

- ^ a b Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 20–21)

- ^ a b Soszka, Hanna. "Analiza zmian stanu jednolitych części wód powierzchniowych jeziornych reperowych badanych w latach 2010–2013" [Analysis of Changes in the Status of Reference Lake Surface Waters Studied in 2010–2013] (PDF). Główny Inspektorat Ochrony Środowiska. Retrieved 2025-05-31.

- ^ Cydzik, Dorota; Soszka, Hanna (1988). Atlas stanu czystości jezior Polski badanych w latach 1979–1983 [Atlas of the Purity Status of Polish Lakes Studied in 1979–1983] (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Geologiczne. pp. 135–145. ISBN 83-220-0338-2.

- ^ Cydzik, Dorota; Kudelska, Danuta; Soszka, Hanna (2000). Atlas stanu czystości jezior Polski badanych w latach 1994–1998 [Atlas of the Purity Status of Polish Lakes Studied in 1994–1998] (in Polish). Warsaw: Główny Inspektorat Ochrony Środowiska. pp. 67–71. ISBN 83-7217-103-3.

- ^ a b Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 21–24)

- ^ Woś (1999, p. 185)

- ^ a b c d Woś (1999, pp. 190–191)

- ^ Woś (1999, p. 146)

- ^ a b c Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 25–30)

- ^ Zielony & Kliczkowska (2012, p. 68)

- ^ Zielony & Kliczkowska (2012, pp. 192–193)

- ^ Zielony & Kliczkowska (2012, pp. 125–130)

- ^ a b Zielony & Kliczkowska (2012, pp. 90–91)

- ^ a b Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, p. 136)

- ^ Waloch, Piotr (2009). "Stan zachowania wybranych torfowisk nakredowych Polski Północno-Zachodniej" [Conservation Status of Selected Chalk Peatlands in Northwest Poland] (PDF). Przegląd Przyrodniczy (in Polish). XX: 59. ISSN 1230-509X.

- ^ Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 32–35)

- ^ a b Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 96–99)

- ^ Śmietana, Przemysław (2008). "Ocena możliwości realizacji restytucji raka szlachetnego do wód śródleśnych na podstawie doświadczeń reintrodukcji tego gatunku w Zaborskim Parku Krajobrazowym" [Assessment of Noble Crayfish Restoration in Inland Waters Based on Reintroduction Experiences in Zaborski Landscape Park]. Studia i Materiały Centrum Edukacji Przyrodniczo-Leśnej. 18. Rogów: Centrum Edukacji Przyrodniczo-Leśnej w Rogowie: 193–214. ISSN 1509-1414.

- ^ a b Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 113–118)

- ^ "Projekt "Ochrona naturalnego tarła łososia atlantyckiego i troci wędrownej w dorzeczu rzeki Słupi"" [Project "Protection of Natural Spawning of Atlantic Salmon and Sea Trout in the Słupia River Basin"]. Stowarzyszenie Proekologiczne Słupia (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2015-02-08.

- ^ Głowaciński (2001, pp. 293–295)

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Żaba wodna" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Edible Frog]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-28.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Żaba jeziorkowa" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Pool Frog]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-25.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Żaba śmieszka" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Marsh Frog]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-27.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Żaba moczarowa" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Moor Frog]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-27.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Żaba trawna" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Common Frog]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-25.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Ropucha szara" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Common Toad]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-25.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Ropucha zielona" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: European Green Toad]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-27.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Ropucha paskówka" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Natterjack Toad]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-25.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Grzebiuszka ziemna" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Common Spadefoot]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-25.

- ^ a b Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 110–112)

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Traszka zwyczajna" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Smooth Newt]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-25.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Traszka grzebieniasta" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Northern Crested Newt]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-27.

- ^ a b "Rozporządzenie Ministra Środowiska z dnia 6 października 2014 r. w sprawie ochrony gatunkowej zwierząt" [Regulation of the Minister of the Environment of 6 October 2014 on the Species Protection of Animals]. isap.sejm.gov.pl (in Polish). 6 October 2014. Retrieved 2025-05-31.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Żółw błotny" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: European Pond Turtle]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2019-09-26.

- ^ "Atlas płazów i gadów Polski. Żółw ozdobny" [Atlas of Amphibians and Reptiles of Poland: Pond Slider]. Instytut Ochrony Przyrody PAN (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2020-06-27.

- ^ Głowaciński (2001, p. 110)

- ^ a b c Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 102–109)

- ^ Głowaciński (2001, pp. 143–144)

- ^ Głowaciński (2001, pp. 134–135)

- ^ Głowaciński (2001, pp. 148–149)

- ^ Głowaciński (2001, pp. 136–137)

- ^ Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, pp. 99–102)

- ^ Głowaciński (2001, pp. 42–43)

- ^ a b c d e Kondracki (2014, p. 72)

- ^ a b Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, p. 184)

- ^ Jasnowska & Jasnowski (1983, p. 190)

- ^ "Dane geoprzestrzenne Generalnej Dyrekcji Ochrony Środowiska" [Geospatial Data of the General Directorate for Environmental Protection]. Generalna Dyrekcja Ochrony Środowiska (in Polish). Archived from the original on 2014-08-03.

- ^ "Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny" [National Geological Institute]. Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny (in Polish). Retrieved 2025-05-31.

Bibliography

- Głowaciński, Zbigniew, ed. (2001). Polska czerwona księga zwierząt [Polish Red Data Book of Animals] (in Polish). Vol. 1. Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Rolnicze i Leśne. ISBN 83-09-01735-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Jasnowska, Janina; Jasnowski, Mieczysław (1983). Pojezierze Zachodniopomorskie [West Pomeranian Lake Land] (in Polish). Warsaw: Wiedza Powszechna. ISBN 83-214-0359-X.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Kondracki, Jerzy (2014). Geografia regionalna Polski [Regional Geography of Poland] (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. ISBN 978-83-01-16022-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Woś, Alojzy (1999). Klimat Polski [Climate of Poland] (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. ISBN 83-01-12780-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Zielony, Roman; Kliczkowska, Anna (2012). Regionalizacja przyrodniczo-leśna Polski 2010 [Natural-Forest Regionalization of Poland 2010] (in Polish). Warsaw: Centrum Informacyjne Lasów Państwowych. ISBN 978-83-61633-62-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)