Vittorio Storaro

Vittorio Storaro | |

|---|---|

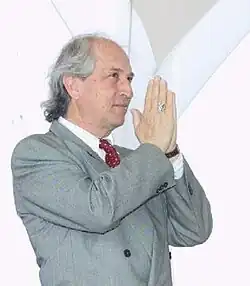

Storaro at Cannes in 2001 | |

| Born | 24 June 1940 |

| Education | Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia |

| Years active | 1960–2023 |

| Organization(s) | American Society of Cinematographers Associazione Italiana Autori della Fotografia Cinematografica |

Vittorio Storaro, A.S.C., A.I.C. (born 24 June 1940), is an Italian cinematographer, widely recognized as one of the best and most influential in cinema history.[1][2][3][4]

Over the course of 50 years, he has collaborated with directors like Bernardo Bertolucci[5], Francis Ford Coppola, Warren Beatty, Woody Allen, and Carlos Saura.

Storaro is one of three living people to have won the Academy Award for Best Cinematography three times, a position he shares with Robert Richardson and Emmanuel Lubezki.

Early life and education

Born in Rome, Storaro is the son of a film projectionist.

He began studying photography at the age of 11, and at the age of 18, he went on to formal cinematography studies at the national Italian film school, Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia.[6]

Career

Storaro's philosophy is largely inspired by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's theory of colors, which focuses in part on the psychological effects that different colors have and the way in which colors influence our perceptions of different situations.[7]

He first worked with Bernardo Bertolucci on The Conformist (1970)[8]. He then worked on Dario Argento's first directorial feature The Bird with the Crystal Plumage (1970), which is considered a landmark in the giallo genre.[9]

With Francis Ford Coppola, Storaro could make his American film debut with Apocalypse Now (1979),[10] which earned him his first Academy Award for Best Cinematography.[11]

Storaro went to win two more Academy Awards in the 1980s, one with Warren Beatty's Reds (1981)[12], and one for Bertolucci's The Last Emperor (1987).[12][13]

In 2002, Storaro completed the first in a series of books that articulate his philosophy of cinematography.[14]

He was the cinematographer for a BBC co-production with Italian broadcaster RAI of Verdi's Rigoletto over two nights on the weekend of 4 and 5 September 2010.[15]

Though working primarily with film cameras, Woody Allen's feature Café Society (2016) was Storaro's first project to be shot digitally.[16]

In 2017, Storaro was honored with the George Eastman Award.[17] The same year he also attended the New York Film Festival at which he debated with Edward Lachman on cinematography and its transition from film to digital.[18]

With his son Fabrizio, he created the Univisium format system to unify all future theatrical and television movies into one respective aspect ratio of 2.00:1.[19] As of 2023, this unification has not happened, and the universal replacement of 4:3 televisions by large, wide-screen displays greatly reduces the need to modify scope-ratio films for home theater presentation.

Personal life

Storaro is known for stylish, fastidious, and flamboyant personal fashion. Francis Ford Coppola once noted, "Vittorio is the only man I ever knew that could fall off a ladder in a white suit, into the mud, and not get dirty."[20]

Filmography

Feature film

Documentary film

| Year | Title | Director |

|---|---|---|

| 1994 | Roma imago urbis | Luigi Bazzoni |

| 1995 | Flamenco | Carlos Saura |

| 2010 | Flamenco Flamenco |

Television

| Year | Title | Director |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | Eneide | Franco Rossi |

Miniseries

| Year | Title | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1974 | Orlando Furioso | Luca Ronconi | With Arturo Zavattini |

| 1983 | Wagner | Tony Palmer | |

| 1986 | Peter the Great | Marvin J. Chomsky Lawrence Schiller |

|

| 2000 | Frank Herbert's Dune | John Harrison | |

| 2007 | Caravaggio | Angelo Longoni |

TV movies

| Year | Title | Director | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Tosca: In the Settings and at the Times of Tosca | Brian Large | |

| Writing with Light: Vittorio Storaro | David M. Thompson | Documentary film | |

| 2000 | La traviata | Pierre Cavassilas | |

| 2010 | Rigoletto a Mantova |

Awards and nominations

| Year | Category | Title | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Best Cinematography | Apocalypse Now | Won | [21] |

| 1982 | Reds | Won | ||

| 1988 | The Last Emperor | Won | ||

| 1991 | Dick Tracy | Nominated |

| Year | Category | Title | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | Best Cinematography | Apocalypse Now | Nominated | [22] |

| 1983 | Reds | Nominated | [23] | |

| 1989 | The Last Emperor | Nominated | [24] | |

| 1991 | The Sheltering Sky | Won | [25] |

American Society of Cinematographers

| Year | Category | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Outstanding Cinematography | The Last Emperor | Nominated |

| 1991 | Dick Tracy | Nominated | |

| 2001 | Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography in a Limited Series | Dune | Nominated |

| Lifetime Achievement Award | Won | ||

| Year | Category | Title | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | Best Cinematography | Goya en Burdeos | Won | [26] |

| Year | Category | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | Best Cinematography for a Miniseries or Special | Peter the Great | Nominated |

| 2001 | Frank Herbert's Dune | Won |

| Year | Category | Title | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | Technical Grand Prize | Tango, no me dejes nunca | Won | [27] |

International Film Festival of India

| Year | Category | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | Lifetime Achievement Award | Won | [28] |

British Society of Cinematographers

| Year | Category | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | Best Cinematography | Apocalypse Now | Nominated |

| 1988 | The Last Emperor | Won | |

| 1990 | Dick Tracy | Nominated |

National Society of Film Critics

| Year | Category | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1972 | Best Cinematography | The Conformist | Won |

New York Film Critics Circle Awards

| Year | Category | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | Best Cinematography | The Sheltering Sky | Won |

| 1990 | The Last Emperor | Won |

Los Angeles Film Critics Association

| Year | Category | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | Best Cinematography | Reds | Won |

| 1988 | The Last Emperor | Won |

| Year | Category | Result |

|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Lifetime Achievement Award | Won |

| Year | Category | Title | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | Best Cinematography | Flamenco (de Carlos Saura) | Nominated |

| 1999 | Tango, no me dejes nunca | Nominated | |

| 2000 | Goya en Burdeos | Won |

References

- ^ Kay, Jeremy (16 October 2003). "And the 11 most influential cinematographers of all time are..." Screen Daily. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro Warns of "Major Problem" in the Field". The Hollywood Reporter. 4 June 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ "The 10 Most Visually Stunning Movies Shot by Vittorio Storaro". Taste of Cinema - Movie Reviews and Classic Movie Lists. 15 September 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (9 July 2003). "Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro reveals his inspiration". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. OCLC 900948621.

- ^ Pizzello, Stephen (6 July 2018). "Storaro and Bertolucci Celebrated at Milan International Film Festival". American Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Back in Time: Vittorio Storaro AIC, ASC / The Early Life of Mohammed". British Cinematographer. 27 May 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC personally details the richly hued artistic strategy he created to shoot Woody Allen's period drama". American Cinematographer. 30 November 2017.

- ^ Berardinelli, James (1994). "Review: The Conformist". ReelViews. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Gallant, Chris (7 June 2018). "Where to begin with giallo". BFI. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Pizzello, Stephen (24 August 2017). "Flashback: Apocalypse Now". American Cinematographer.

- ^ "Mighty Tome: Vittorio Storaro AIC ASC / The Art of Cinematography". British Cinematographer. 3 June 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ a b "Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro: Master of Lights and Colors". italoamericano.org. 20 September 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Bob Fisher (2004). "Vittorio Storaro: Maestro of Light". ICG Magazine. International Cinematographers Guild. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017 – via scrapsfromtheloft.com.

- ^ Jones, Jonathan (9 July 2003). "Painting with light". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Adetunji, Jo (25 July 2010). "Verdi's Rigoletto given 'cinematic' makeover for BBC". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Giardina, Carolyn (15 July 2016). "Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro on Filming 'Cafe Society' Digitally: "You Can't Stop Progress"". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ "Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC Honored with George Eastman Award". American Society of Cinematographers. 21 March 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- ^ Chris O'Falt (13 October 2017). "Digital Cinematography Smackdown: Vittorio Storaro and Ed Lachman Debate, With Love". IndieWire. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Joe Foster (24 October 2017). "The remarkable rise of the Univisium 2:1 aspect ratio". RedSharkNews. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- ^ Kees van Oostrum (2 January 2018). "President's Desk: Men in White Suits - The American Society of Cinematographers". American Cinematographer.

- ^ "Vittorio Storaro". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ "Past Winners and Nominees – Film Nominations 1979". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ "Past Winners and Nominees – Film Nominations 1982". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ "Past Winners and Nominees – Film Nominations 1988". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ "Past Winners and Nominees – Film Nominations 1990". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ^ "European Film Awards 2000 – The Winners". European Film Awards. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Tango". festival-cannes.com. Festival de Cannes. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ^ Shekhar, Mimansa (16 January 2021). "IFFI 2021: Everything to know about the film festival". Indian Express.

- General

- "Vittorio Storaro Movie Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "Vittorio Storaro > Filmography". Allmovie. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- "Search Page". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 16 January 2008.. Note: User must define search parameters, i.e. "Vittorio Storaro."

Further reading

- Masters of Light - Conversations with cinematographers (1984) Schaefer, S & Salvato, L., ISBN 0-520-05336-2

- Writer of Light: The Cinematography of Vittorio Storaro, ASC, AIC (2000) Zone, R., ISBN 0-935578-18-8

- Vittorio Storaro: Writing with Light: Volume 1: The Light (2002) Storaro, V., ISBN 1-931788-03-0