National Youth and Children's Palace

| National Youth and Children's Palace | |

|---|---|

მოსწავლე ახალგაზრდობის ეროვნული სასახლე | |

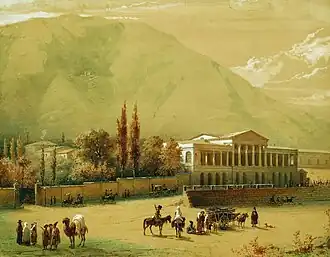

National Palace in september 2023 | |

| Former names | Viceroy's palace; Pioneers' palace |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Renaissance |

| Address | 6, Rustaveli Ave. |

| Town or city | Tbilisi |

| Country | Georgia |

| Current tenants | Tbilisi National Youth Palace |

| Completed | 1818 |

| Renovated | 1st renovation – 1847 2nd renovation – 1869 (current façade) 3rd renovation – 1941 |

| Renovation cost | 3rd renovation: up to 15 million rubles 4th renovation: 53.9 million GEL [1] |

| Renovating team | |

| Architect(s) | 1st renovation – Nikolay Semionov 2nd renovation (current façade) – Otto Jakob Simonson 3rd renovation – Archil Kurdiani 4th renovation – Merab Bochoidze[2] |

| Website | |

| youthpalace nationalpalace | |

| Official name | Youth Palace |

| Designated | October 1, 2007 |

| Item Number in Cultural Heritage Portal | 4976 |

| Date of entry in the registry | October 11, 2007 |

National Youth and Children's Palace (Georgian: მოსწავლე ახალგაზრდობის ეროვნული სასახლე), sometimes referred to as Pioneers' Palace, National Palace, or by its original name, Viceroy's Palace, is a historic building located on Rustaveli Avenue in Tbilisi, Georgia.

The original building, constructed in 1802, after the establishment of the Imperial Russian Rule in Georgia, served as the residence of the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasus in Tiflis. After several reconstructions, a new palace was built in 1818, designed by architect Braunmiller. The palace was reconstructed in 1847, by architect Nikolai Semyonov, who gave the palace a classical look and constructed a garden on the left side of the palace. It underwent a second renovation in 1869, led by Otto Jakob Simonson, a German architect working in Tbilisi. He enlarged the palace and gave it a Renaissance look.[3]

During the various periods of Russian Imperial rule in Georgia, the palace was sometimes the residence and palace of the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasus, and sometimes of the Viceroy.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, the palace housed the government of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. On May 26, 1918, the federation announced its dissolution and the National Council of Georgia, convened at the palace on the same day, declared Georgia's independence at 5:10 p.m. Two days later, the independence of the Democratic Republic of Azerbaijan and the First Republic of Armenia was declared in the palace. Following the declaration of independence, the palace housed the government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia and the National Council, which, following the 1919 parliamentary elections, was replaced by the Constituent Assembly of Georgia. On February 21, 1921, the palace hosted the adoption of the Constitution of the Democratic Republic by the Constituent Assembly.

After the Sovietization of Georgia, the palace housed the Georgian Revolutionary Committee, then the governments of the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and Soviet Georgia.[4] In 1937, the soviet government decided to open a Pioneers Palace, a nonformal educational institution for children. After the reconstruction, the palace reopened on May 2, 1941, to house the educational institution for children with learning, art and cultural, musical, theatrical, botanical studios, etc. Since 1941, the palace has been housing Tbilisi National Youth Palace.[5]

The Palace is listed Cultural Heritage Monument of Georgia.[6]

History

Early history

Prior to the 19th century, the area of present-day Rustaveli Avenue, Freedom Square, Orbeliani Square and Tchanturia Street lay outside the city walls of Tiflis and was called Garetubani, meaning peripheries.[7] This area was cultivated with gardens and vineyards that belonged to the Georgian Royal Family.[8]

After the Russian conquest of the Caucasus and the annexation of the Georgian Kingdoms, Russian imperial authority was established in Georgia. Russian Empire appointed Karl Knorring the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasus.[3] In 1802, in Garetubani, Georgian architects constructed a two-building complex [7] for the Commander-in-Chief, serving as his residence and office.

This complex was demolished and a new classical building was constructed in 1807.

Current building

In 1818, the previous buildings were demolished, and architect Braunmiller constructed a new palace on the same site. Later, the building was expanded, with the small rooms replaced by larger ones. The expansion included private apartments for the commander-in-chief, study rooms, a billiard room, clerks’ rooms and a Winter Garden.[3][9]

In 1844, Petersburg architect Nikolay Semionov significantly altered the palace's appearance. He gave it a classical look and installed sculptures of Hercules and Minerva on the facade.[10][3]

By the end of 1850, there was a proposal to construct a new, larger and more representative building for the Viceroy on the Gunib Square, where the present day Parliament building stands. The project was never realizes, and it was decided to remodel the old one.[3]

In 1865, German architect Otto Jakob Simonson, who was invited by the Viceroy of Caucasus to work under his administration on several projects, started the reconstruction of the palace.[11]

Simonson expanded the palace, moved its side wings forward and made minor alterations to the main façade. He enlarged the central reception, designed a large foyer, a grand staircase and a large dining room with a portico and a salon in the north part of the palace and designed a working office of the Viceroy, reception, living room and an exhibition hall with a terrace and a wide, open staircase to the garden in the south part of the palace. He also constructed entertainment areas and dedicated quarters for staff.[11] Simonson remodeled the palace with a Renaissance-style facade and enriched the interior with ornate stucco work. He designed the ballroom in the Persian style, adorned its ceilings with stalactite vaulting, encrusted and curved its walls with ornamental mirrors, installed stained glass windows and hung gilded chandeliers. He also added marble chimneys in halls, living rooms, reception, foyer and the lobby.[12] Simonson finished the reconstruction in 1869.

-

Façade

Façade -

Viceroy's Cabinet

Viceroy's Cabinet -

Interior of the Palace, c. 1865

Interior of the Palace, c. 1865 -

"Mirror" Ballroom

"Mirror" Ballroom -

Staircase to the garden

Staircase to the garden -

Sketch by Simonson

Sketch by Simonson

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, the palace welcomed several distinguished guests. In the 1830s, it was visited by Nicholas I of Russia. In 1858, the Caucasus Viceroy, Prince Aleksandr Baryatinsky, hosted Alexandre Dumas and Jean-Pierre Moynet at a New Year gala held in the palace.[13] In August 1873, during his tour of Europe, Naser al-Din Shah Qajar was received at the palace by the Commander-in-Chief of the Caucasus, Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich. The Shah spent several days at the residence and later recorded his impressions in his diary.[14] In November 1914, Emperor Nicholas II stayed at the palace during his tour of the Caucasus.

On March 15, 1917, after receiving a telegram from Petrograd about the abdication of the Tsar, Noe Zhordania, a leading social-democratic politician, along with Isidore Ramishvili visited the palace to inform the Viceroy about the latest political developments in the imperial capital.[15] On March 20, 1917, Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich, the last Viceroy in the Caucasus, left Tiflis for Petrograd.[16] The Special Transcaucasian Committee, authorized by the provisional government to govern the Caucasus, took over the palace.[17] Following the October Revolution and the subsequent dissolution of the provisional government in October 1917, the committee immediately lost its authority to govern the territory.[17] The governance of the territory was handed to the Transcaucasian Commissariat, composed of three Georgians, three Azerbaijanis, three Armenians and two Russians.[18]

On February 3, 1918, in the White Hall of the palace, Evgeni Gegechkori, the chairman of the commissariat, opened a meeting of deputies elected from Transcaucasia to the Russian Constituent Assembly to discuss the convention of a legislative body.[19] Later that month, on February 23, the Commissariat convened the Transcaucasian Seim —a representative and legislative body of state power in the region. On March 26, the Seim approved the composition of a new government proposed by Gegechkori, thereby abolishing the Commissariat.[20] Subsequently, on April 22, 1918, the Seim declared the independence of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic.

On May 26, 1918, the Transcaucasian Seim held its final meeting in the same White Hall of the palace. At 3:00 PM, it declared the dissolution of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic. Shortly after, at 4:50 PM, the Georgian National Council, chaired by Noe Jordania, convened in the palace with 42 members and 36 candidate members. Jordania delivered a speech and read aloud the Declaration of Independence. The National Council unanimously approved the declaration and also defined the structure and composition of the new government.[21][22]

Two days later, on May 28, 1918, the White Hall of the palace again became the site of historic events, as both the Azerbaijani National Council and the Armenian representatives declared the independence of Azerbaijan and Armenia, respectively.[22][23] Following Georgia’s declaration of independence, the National Council and the Government of the Democratic Republic of Georgia used the palace as their seat for a year. In March 1919, Georgia held elections to its Constituent Assembly, which replaced the National Council and confirmed the legal validity of the Georgian Declaration of Independence. The Assembly, continuing its work in the palace, formed a Constitutional Commission tasked with drafting a new constitution.

In March 1919, Georgia held elections to the Constituent Assembly, which replaced the National Council and confirmed the legal validity of the Georgian Declaration of Independence. The Assembly, continuing its work in the palace, formed a Constitutional Commission tasked with drafting a new constitution.[21]

In November 1919, the palace hosted a conference of heads of governments of Transcaucasian republics. On November 23, through the mediation of Georgian Foreign Minister Evgeni Gegechkori, British High Commissioner Sir Oliver Wardrop and Acting allied High Commissioner, US Army Colonel James C. Ray, Armenia and Azerbaijan signed a peace treaty[24][25]

.png)

The drafting of the constitution took over a year. However, after the Russian Red Army invaded Georgia in February 1921, the Constituent Assembly was forced to expedite the adoption process. On February 21, 1921, an extraordinary session of the assembly was held in the palace, where the Constituent Assembly unanimously adopted the Constitution of the Democratic Republic of Georgia. [26][27]

Following the Soviet occupation of Georgia, the palace became the headquarters of the Georgian Revolutionary Committee. From 1922, it housed the central executive committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the Transcaucasian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic.[4][5] From 1922 until her death, Keke Geladze, Stalin's mother, also lived in the palace.[4].

In 1937, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia decided to establish a Pioneers Palace, a nonformal educational institution for children. Georgian architect Archil Kurdiani began the reconstruction of the palace to accommodate this purpose.

Following its reconstruction, the interior of the palace was equipped with study rooms, science labs, workshops, sport areas and entertainment halls. Other facilities included a lecture hall, a puppet theatre, and a reading room. The reconstruction project cost approximately 15 million rubles.[5] The Palace of Pioneers and Students was officially inaugurated on May 2, 1941. Later, the brick fence bordering Rustaveli Avenue was replaced by a metal fence mounted on granite columns adorned with traditional Georgian ornaments.

Over time, the palace underwent significant expansion. On the day of its opening, the institution accommodated around 1,800 children across 24 classrooms in six departments. By 1981, enrollment had increased to approximately 10,000 children participating in activities within 11 departments.

Throughout its history, the palace received visits from several prominent political and public figures, including Dolores Ibárruri, Indira Gandhi, Jorge Amado, Ted Kennedy, Ivan Papanin and others.[5]

Several Georgian movies, including Keto and Kote, Data Tutashkhia, Once Upon a Time There Was a Singing Blackbird, Don't Grieve and others were shot in the palace.[28][29]

In September 2005, the Tbilisi city government announced plans to establish a state choreographic school within the palace,[30] appointing renowned ballerina Nino Ananiashvili as its director. As part of this initiative, the existing institution and its students were to be relocated to a different site. The decision sparked public protests in Tbilisi,[31] over displacing the institution and repurposing the palace. Following the public outcry, the government ultimately reconsidered and altered its decision.

In 2019, the Tbilisi city government decided to undertake a comprehensive rehabilitation and restoration of the palace.[32] The project, managed by the Tbilisi Development Fund, began with the preparation of restoration plans and was officially launched that year. Initial works included updating heating, cooling, and electrical systems, followed by structural reinforcement and restoration of the building’s facade, roof, and interior decorative halls such as the Mirror, the Marble, and the White Halls.[33] Rehabilitation proceeded in phases, with Block B completed in 2021, including restoration of underground communications, internal spaces, and the facade. As of late 2024, restoration of Block A’s halls and educational spaces is nearing completion, along with improvements to the courtyard and surrounding fences. The entire project, part of the “New Tbilisi” initiative, is valued at approximately 54 million Georgian Lari and as of December 2024, remains in progress.[1]

Architecture

The palace is situated on elevated ground along Rustaveli Avenue, resting on a stone plinth. Due to the sloping terrain, the facade facing April 9 Street varies in height. The building is composed of individual blocks that protrude outward, forming distinct risalits. On the opposite side is a palace garden with a terrace. The main facade is symmetrical, while the first floor features entrances within prominently raised risalits. Above these entrances are balconets with molded balustrade railings. Flanking the balcony openings are round Corinthian pilasters that add to the risalits’ grandeur, which are supported by Renaissance-style arches. A similar architectural motif appears on the risalits facing April 9 street. [34]

The central entrance is located in the middle of the building and is topped by a row of windows. Between the risalits, arched galleries span both floors, giving the facade a rhythmic, solid appearance. Along April 9 Street, the facade is divided into several sections. The rear part is more modestly decorated, with minimal ornamentation—mainly a single Doric pilaster between rectangular windows supporting a series of arches. The garden-facing facade follows a similar design. In contrast, the rear and inner courtyard facades are plainer, with significantly fewer decorative elements.[35][36]

While the exterior is relatively restrained, the palace’s interior—especially the central foyer and ceremonial halls—is richly decorated.

See also

References

- ^ a b "მოსწავლე-ახალგაზრდობის ეროვნული სასახლის სარეაბილიტაციო სამუშაოები დასკვნით ეტაპზეა" [Rehabilitation works of the National Palace of Students and Youth are in the final stage]. 1tv.ge (in Georgian). Tbilisi. 2024-12-03. Archived from the original on 2025-01-15.

- ^ LLC 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "History of National Palace". National Palace -. National Palace. 29 March 2021. Archived from the original on 2022-04-19. Retrieved 2022-04-19.

- ^ a b c Elisashvili 2013.

- ^ a b c d Tsereteli et al. 1981.

- ^ "კულტურული მემკვიდრეობის პორტალი".

- ^ a b Kvirkvelia 1985, Golovini Prospect.

- ^ National Palace 2017, p. 5.

- ^ National Palace 2017, p. 6.

- ^ National Palace 2017, p. 7.

- ^ a b National Palace 2017, p. 9.

- ^ National Palace 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Moyner, Jean-Pierre, ვოლგა და კავკასია ალექსანდრე დიუმასთან ერთად [Volga and Caucasus with alexander Dumas] (PDF) (in Georgian), archived (PDF) from the original on 2025-03-20, retrieved 2025-05-13

- ^ Naser al-Din Shah Qajar (1874). The Diary of H.M. the Shah of Persia, During His Tour Through Europe in A.D. 1873. Translated by J.W. Redhouse. London: John Murray.

- ^ Rayfield 2012, p. 323.

- ^ "ახალი ამბები" [News] (PDF). საქართველო [Georgia] (in Georgian). No. 53. Tiflis. 1917-03-21.

- ^ a b Rayfield, p. 323.

- ^ Brisku 2020.

- ^ "ახალი ამბები" [News] (PDF). ერთობა (in Georgian). No. 17. Tiflis. 1918-02-03.

- ^ "ახალი მთავრობა" [New Government] (PDF). ერთობა (in Georgian). No. 60. Tiflis. 1918-03-28.

- ^ a b Shvelidze 2018.

- ^ a b National Palace 2017, p. 37.

- ^ Shvelidze 2018, p. 110.

- ^ "საქართველო-აზერბაიჯან-სომხეთის შეთანხმება" [Agreement between Georgia, Azerbaijan and Armenia] (PDF). ჩვენი ქვეყანა[Our Country] (in Georgian). No. 210. Tiflis. 1919-11-25.

- ^ Hille 2010, pp. 146, 167.

- ^ National Palace 2017, p. 39.

- ^ Demetrashvili et al. 2011, p. 36.

- ^ National Palace 2017, p. 41.

- ^ Villette & Ubilava-De Graaf 2019.

- ^ "First they decided, then they will discuss: that is, how the Student Palace changed its address" (PDF). 24 Saati. 195 (1055): A3. 2005-08-31.

- ^ "თბილისში, მოსწავლე-ახალგაზრდობის სასახლის წინ გაიმართა საპროტესტო აქცია-კონცერტი" [A protest rally-concert was held in front of the Student and Youth Palace in Tbilisi]. Radio Free Europe-Radio Liberty (in Georgian). Tbilisi. 2005-09-05. Archived from the original on 2025-05-25.

- ^ "მოსწავლე-ახალგაზრდობის სასახლის შენობას რეაბილიტაცია ჩაუტარდება" [The Student and Youth Palace building will be rehabilitated]. 1tv.ge (in Georgian). 2019-02-06. Archived from the original on 2022-10-28.

- ^ "მოსწავლე-ახალგაზრდობის ეროვნული სასახლის რეაბილიტაცია გრძელდება" [Rehabilitation of the National Palace of Students and Youth continues]. 1tv.ge (in Georgian). Georgian Public Broadcaster. 2022-08-10. Archived from the original on 2022-10-02.

- ^ "ᲔᲠᲝᲕᲜᲣᲚᲘ ᲡᲐᲡᲐᲮᲚᲔ ᲝᲠᲡᲐᲣᲙᲣᲜᲝᲕᲐᲜᲘ ᲘᲡᲢᲝᲠᲘᲘᲗ" [National palace with two centuries of history]. um.ge (in Georgian). Urban Media. 2025-01-06. Archived from the original on 2025-07-25.

- ^ LLC 2020, p. 2.

- ^ "National Palace". Scan Tbilisi. Archived from the original on 2025-03-21.

Works cited

- National Palace (2017). National Palace Catalogue. Tbilisi, Georgia. ISBN 978-9941-27-227-1. Archived from the original on 2024-01-28. Retrieved 2024-01-28.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - მოსწავლე ახალგაზრდობის ეროვნული სასახლის სარესტავრაციო-სარეაბილიტაციო სამუშაოების საკვლევი-საპროექტო დოკუმენტაცია – სასახლის ძირითადი ნაგებობა (ბლოკი-ა) რესტავრაცია-რეაბილიტაციის საპროექტო დოკუმენტაცია [Research and design documentation for the restoration and rehabilitation works of the National Palace of Students and Youth – Restoration and rehabilitation design documentation of the main building of the palace (block-A)] (PDF). LLC Monuments and Landmarks Design, Research and Restoration Institute (in Georgian). 2020. Archived from the original on 2025-03-21.

- Kvirkvelia, Tengiz (1985). ძველთბილისური დასახელებანი [Old Tbilisi names] (in Georgian). Tbilisi: Soviet Georgia. Retrieved 2024-02-15.

- Tsereteli, G; Gvazava, K; Kasradze, A; Dogonadze, D (1981). Jhgenti (ed.). ჩვენი სასახლე [Our Palace] (in Georgian). Tbilisi: Nakaduli.

- Brisku, Adrian (2020), "The Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic (TDFR) as a 'Georgian' responsibility", Caucasus Survey, 8 (1): 31–44, doi:10.1080/23761199.2020.1712902, S2CID 213610541

- Rayfield, Donald (2012). Edge of Empires: A History of Georgia. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1780230306.

- Elisashvili, Aleksandre (2013). "Viceroy palace". Tbilisi then and now. Tbilisi: Sulakauri Publishing. ISBN 978-9941-15-897-1.

- Tchanturidze, Salome; Khositashvili, Mirian; Barbakadze, Ana (2021). Javakhishvili, Kato (ed.). Green City. Tbilisi: National Parliamentary Library of Georgia. ISBN 978-9941-9653-8-8.

- Villette, Aurelien; Ubilava-De Graaf, Dali (2019). Tiflis Tbilisi: A story in pictures. Tbilisi: Palitra L Publishing. ISBN 978-9941-29-394-8.

- Shvelidze, Dimitri, ed. (2018). საქართველოს დემოკრატიული რესპუბლიკა: (1918-1921) ენციკლოპედია-ლექსიკონი [Democratic Republic of Georgia: (1918-1921) encyclopedia-dictionary] (in Georgian). Tbilisi, Georgia: Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University Press. ISBN 978-9941-13-718-1.

- Hille, Charlotte (2010). State Building and Conflict Resolution in the Caucasus. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-4136-6. OCLC 668211543.

External links

![]() Geographic data related to National Youth and Children's Palace at OpenStreetMap

41°41′46″N 44°47′57″E / 41.6961°N 44.7991°E

Geographic data related to National Youth and Children's Palace at OpenStreetMap

41°41′46″N 44°47′57″E / 41.6961°N 44.7991°E