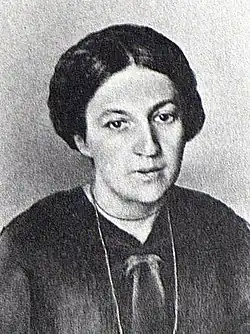

Varvara Yakovleva (politician)

Varvara Yakovleva | |

|---|---|

Варвара Яковлева | |

| |

| People's Commissar for Finance of the RSFSR | |

| In office January 1930 – September 1937 | |

| Premier | Sergei Syrtsov (until 1930) Daniil Sulimov (until 1937) Nikolai Bulganin |

| Preceded by | Nikolay Milyutin |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Sokolov[1] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 19 December 1884 (N.S.) Moscow, Russian Empire |

| Died | 11 September 1941 (aged 56) Oryol Prison, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | RSDLP (Bolsheviks) (1904–1918) All-Union Communist Party (bolsheviks) (1918–1937) |

| Spouse | |

| Relations | Nikolai Yakovlev, brother |

| Children | 2 |

Varvara Nikolaevna Yakovleva (Russian: Варвара Николаевна Яковлева; 19 December [O.S. 7 December] 1884 – 11 September 1941) was a Russian revolutionary, prominent Bolshevik party member, Cheka officer, and Soviet government official, who supported Leon Trotsky's attempt to democratize the party in the mid 1920s. She was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 1938 for membership in a "diversionary terrorist organization." She was later shot in the Medvedev Forest massacre in Oryol in 1941.

Early life

Yakovleva was born in December 1884 in Moscow to the middle-class family of a tradesman of Jewish descent. Her father was a convert to Orthodox Christianity.[2][3] Yakovleva joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) in January 1904, at age 19, when she was a student at a women's college in Moscow, where she was studying mathematics and physics, and was immediately involved in the illegal distribution of party literature.[4] She quickly joined the Bolshevik faction of the RSDLP due to agreeing with Vladimir Lenin's more strict definition of party membership, and her strong belief that the Russian bourgeoisie should have no role in the bourgeois-democratic revolutionary tasks in Russia.[5]

During the Russian Revolution of 1905, she was violently assaulted on the breasts, which damaged her health for many years, and was a cause of the tuberculosis that she later contracted in exile in Siberia.[6] She was first arrested in 1906, and again in 1907, and barred from living in Moscow. Arrested again in December 1910, she was sentenced to four years exile in Narym, in Siberia, but escaped, and emigrated to Berlin to get medical treatment for her tuberculosis, which at the time largely consisted of much bed rest, fresh air and nutrition.[7][8] After recovering, at a time when only around one quarter of people with tuberculosis did so,[9] she made her way to Kraków, where she met up with Lenin and made arrangements to smuggle illegal literature and correspondence across the border into Russia.[10] In October 1912, as an agent of the Central Committee of the Bolshevik Party in Moscow, she was arrested for the fourth time by the Okhrana. In 1913, she was sent back to Narym, but escaped again, to St. Petersburg, where she was soon arrested again and deported to Astrakhan.[4]

Career post-1917

Yakovleva was able to return to Moscow late in 1916, and she was appointed secretary of the Moscow regional committee of the Bolshevik Party. In August 1917, she was elected as a candidate for membership in the Bolshevik Central Committee, making her the third most prominent female Bolshevik, after Alexandra Kollontai and Elena Stasova.

On 23 October 1917 (N.S.), Yakovleva took the minutes at the meeting that set the date for the October Revolution for 15 days later, for 7 November (N.S.).[11] In the lead up to, and during, the October Revolution, Yakovleva had a role in organizing the takeover of power in Moscow alongside Nikolai Bukharin. While the Soviet taking of power in Petrograd under Vladimir Lenin, Leon Trotsky and the Military Revolutionary Committee was done relatively quickly, the Soviet taking of power in Moscow took over a week, with Yakovleva playing a major role in the eventual Soviet taking of power in Moscow on 15 November (N.S.). Alexandra Kollontai later stated that "Enormous work was done by Varvara Nikolaevna Yakovleva during the difficult and decisive days of the October Revolution in Moscow", and that Yakovleva "on the battleground of the barricades, showed a resolution worthy of a leader of party headquarters."[12]

In November 1917, Yakovleva was one of four Bolsheviks elected in the Tula electoral district, and one of 183 Bolsheviks elected in the Constituent Assembly election overall. In January 1918, the Constituent Assembly convened for only 13 hours before it was shut down by the Bolshevik Soviet leaders.

On 20 December 1917 (N.S.), Yakovleva was one of eleven people at the meeting at the Smolny Institute in Petrograd that founded the Cheka.[13][14] Yakovleva was then appointed as a member of the collegium of the Cheka by Felix Dzerzhinsky, the Cheka leader. In March 1918, Yakovleva briefly became the head of Vesenkha, the biggest state institution in the RSFSR for the management of the economy, before being replaced by the moderate Alexei Rykov in April 1918.[15]

In late 1917 and early 1918, Yakovleva was one of the most prominent Left Communists, led by Bukharin, who opposed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, a treaty which ended the war between Russia and Germany at the cost of leaving most of Ukraine and the Baltic states under German occupation. In September 1918, Yakovleva was appointed as the deputy head of the Petrograd Cheka.[16] Yakovleva's tenure as the deputy head of the Petrograd Cheka took place during the Red Terror. The Red Terror was unleashed following an unsuccessful attempt on Lenin's life by Fanny Kaplan on 30 August 1918, a day which also saw the successful assassination of the head of the Petrograd Cheka, Moisei Uritsky, by Leonid Kannegisser.[17] From January 1919, as a board member of the People's Commissariat of Food, Yakovleva led food inspections and parties that requisitioned food, her job being to make sure that grain was not destroyed by Kulaks and was used to feed Red Army soldiers during the Russian Civil War. She was known for her severity in this matter.[18]

From December 1920 to March 1921, including at the 10th Congress, Yakovleva again backed Bukharin against Lenin during a dispute over the role of the trade unions.[4][18] Lenin, throughout the trade union debate and also in his speech at the 10th Congress, criticized Bukharin's group for making "theoretical mistakes" and for trying to act as a "buffer".[19]

From December 1920 to April 1921, Yakovleva was secretary of the Moscow party organisation. From April to August 1921, she was secretary of the Siberian party organisation. In February 1922, after the Cheka was dissolved and replaced by the GPU, Yakovleva was appointed as Vice Commissar in the RSFSR People's Commissariat for Education.[20][4]

As Bukharin slowly moved rightwards inside the Bolshevik Party from 1921 onwards, Yakovleva stayed firmly on the left. In October 1923, Yakovleva signed The Declaration of 46, becoming the most prominent female member of the Leon Trotsky led Left Opposition. In early 1926, the Left Opposition formed an alliance with the New Opposition group led by Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, to form the United Opposition. In October 1927, Yakovleva ended her support for the United Opposition under growing pressure from the Joseph Stalin led government. In December 1927, the United Opposition was suppressed and banned from the Communist Party after the 15th Congress. In December 1929, Yakovleva was appointed RSFSR People's Commissar for Finance, a job in the government that she maintained right up until her September 1937 arrest during the Great Purge.[21][4]

Family

Yakovleva's younger brother, Nikolai Yakovlev (1886–1918), also joined the Bolsheviks in 1904–05, and is reputed to have been arrested 12 times over a decade. In 1914–16, he was in exile in Narym.[22] According to Lenin's widow, he was a "staunch and reliable Bolshevik".[23] In 1916, he was conscripted into the Imperial Army, and stationed in Tomsk, where he was elected Chairman of the Tomsk Soviet after the February Revolution. In mid 1917, he was appointed as the main Bolshevik leader in the wider Siberian Soviet, and later in the year, following the October Revolution, he became the chairman of the Central Executive of the Siberian Soviet. Yakovlev was forced into hiding when White forces advanced in Siberia during the autumn of 1918, during the Russian Civil War. In November 1918, White forces in Siberia, led by Alexander Kolchak, seized control of Siberia through a British sponsored coup d'état. That same month, Nikolai Yakovlev was one of a group of Bolsheviks who was captured by White guards and executed on the spot. He was 32 years old.

Yakovleva's first husband was Pavel Shternberg, whom she converted to Bolshevism. Shternberg died in 1920. They had a daughter, Irina Pavlovna Yakovleva (1915–1987).

In 1921, Varvara Yakovleva married Ivan Smirnov, but this marriage disintegrated after she broke with the Left Opposition in October 1927. After the United Opposition was banned from the Communist Party following the 15th Congress, Smirnov was sentenced to three years of internal exile on 31 December 1927.[24] While Smirnov initially stuck by the Left Opposition despite the wrecking of his marriage and the rising Stalinist pressure, Smirnov later formally capitulated in October 1929 by "renouncing Trotskyism" and "admitting his mistakes", two things which Yakovleva never did, despite her leaving the Left Opposition two years earlier. At the time of Smirnov's capitulation in October 1929, the policies of the Stalin government now appeared closer to what the Left Opposition had been advocating before their suppression in December 1927, especially with Stalin's implementation of the first five-year plan. The first five-year plan, and the Soviet government's ultra-left turn at the time, also played a big role in left communist Yakovleva being appointed to a government job in December 1929 as the RSFSR People's Commissar for Finance.[25]

In May 1930, Smirnov was reinstated in the Communist Party. Smirnov was later arrested by the OGPU in January 1933,[26] and was accused of forming an "anti-party group" that was plotting to remove Stalin from power, resulting in Smirnov being sentenced to five years in a prison labour camp in April 1933. Smirnov refused to do any more capitulations to Stalin, and he was later caught up in the Great Purge, being executed in August 1936 following his conviction in the First Moscow Trial. Yakovleva's daughter with Smirnov, Vladlena Ivanovna Smirnova (1922–1989), fled Moscow after her mother's arrest in September 1937, in order to avoid being placed in an orphanage, and she later worked as a teacher in Siberia. Vladlena later married Dmitri Zolnikov, a lecturer at Novosibirsk State University. Their daughter, Natalya Zolnikova (1949–2018), was one of the foremost historians of the Russian Orthodox Church.[27]

Imprisonment and death

Yakovleva was arrested by the NKVD on 12 September 1937 and taken into custody, where she was charged with sabotage and terrorism against the Soviet Union, and of membership in a "Trotskyite-fascist diversionary terrorist organization", with interrogators bringing up the bisexual Yakovleva's past same-sex relationships as "evidence" of her "Trotskyite-fascist tendencies".[4][28] She was also expelled from the Communist Party.[4] During the Third Moscow Trial in March 1938, she appeared as a witness, to testify that in 1918, Bukharin and her other fellow Left Communist comrades of the time had plotted to arrest and possibly assassinate Lenin, Stalin and Yakov Sverdlov. Bukharin, who was on trial, accused her of talking "patent nonsense".[29] According to the historian Roy Medvedev, Yakovleva's 'evidence' was "a fraudulent deposition written for her by the investigators." Afterwards, Yakovleva asked her cellmates to spread the word - if they survived - that her deposition was lies that she had been forced to sign after torture.[30]

At a secret trial on 14 May 1938, Yakovleva was convicted of sabotage, terrorism and membership in a "Trotskyite-fascist diversionary terrorist organization", and was sentenced to 20 years in prison. She was held in solitary confinement at Oryol Prison, where she was executed on 11 September 1941 in the Medvedev Forest massacre, together with 156 other inmates. The Medvedev Forest massacre came less than three months after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, and 26 days before Nazi troops invaded Oryol.[4] The order to kill her was signed by Stalin.[31] (Several Soviet sources falsely gave the date of her death as 21 December 1944).[18]

She was posthumously rehabilitated in 1958.[18]

References

- ^ "RUSSIA: Commissaresses". Retrieved 10 July 2025.

- ^ "Яковлева Варвара Николаевна (1884-1941)". Мемориальный Музей "Следственния Тюрьма НКВД". Tomsk Museum. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ "К 100-ЛЕТИЮ РЕВОЛЮЦИИ. ВАРВАРА ЯКОВЛЕВА – Мосправда-инфо" (in Russian). 30 March 2017. Retrieved 2021-05-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Shishkin, V.I. "ЯКОВЛЕВА Варвара Николаевна". Библиотека сибирского краеведення. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Shishkin, V.I. "ЯКОВЛЕВА Варвара Николаевна". Библиотека сибирского краеведення. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Stites, Richard (1991). The Women's Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860–1930 (Newwith afterword ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 275. ISBN 0691100586.

- ^ "Planning the Nation: the sanatorium movement in Germany". 23 October 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2025.

- ^ "Tuberculosis Part two: Treatments and cures". 6 February 2024. Retrieved 10 July 2025.

- ^ "Once a leading killer, tuberculosis is now rare in rich countries — here's how it happened". 2 June 2025. Retrieved 10 July 2025.

- ^ Krupskaya, Nadezhda (Lenin's widow) (1970). Memories of Lenin. Panther. p. 205.

- ^ "Meeting of the Central Committee of the R.S.D.L.P.(B.) October 10 (23), 1917". Marxists.org. 23 October 1917. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Women Fighters in the Days of the Great October Revolution". Marxists.org. 11 November 1927. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ "Note To F. E. Dzerzhinsky - With A Draft Of A Decree On Fighting Counter-Revolutionaries And Saboteurs". Marxists.org. 20 December 1917. Retrieved 18 July 2025.

- ^ Stites, Richard (1991). The Women's Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860–1930 (Newwith afterword ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 278. ISBN 0691100586.

- ^ Stites, Richard (1991). The Women's Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860–1930 (Newwith afterword ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 278. ISBN 0691100586.

- ^ Stites, Richard (1991). The Women's Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860–1930 (Newwith afterword ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 279. ISBN 0691100586.

- ^ Stites, Richard (1991). The Women's Liberation Movement in Russia: Feminism, Nihilism, and Bolshevism, 1860–1930 (Newwith afterword ed.). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p. 279. ISBN 0691100586.

- ^ a b c d Encyclopedia of Marxism: Glossary of the People. "Glossary of People: Ya". Encyclopedia of Marxism. Retrieved March 27, 2007.

- ^ "The Trade Unions, The Present Situation, And Trotsky's Mistakes". Marxists.org. 30 December 1920. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ "Russia: Commissaresses". time.com. 29 November 1937. Retrieved 9 July 2025.

- ^ "Russia: Commissaresses". time.com. 29 November 1937. Retrieved 9 July 2025.

- ^ "Я́ковлев Никола́й Никола́евич". C Нарымом связанные судьбы. Tomskmuseum.ru. Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Krupskaya. Memories. p. 224.

- ^ Todd, Allan (2012). The Soviet Union and Eastern Europe 1924–2000. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Russia: Commissaresses". time.com. 29 November 1937. Retrieved 9 July 2025.

- ^ Todd, Allan (2012). The Soviet Union and Eastern Europe 1924–2000. Cambridge University Press. p. 49.

- ^ Petrov, S.G. "Наталя Дмиетриевна Золникова: (Некролог)". Церковно-Научный Центр "Православная Энциклопедия". Retrieved 30 December 2020.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Homosexuality, Volume 2 – Marxism

- ^ Report of Court Proceedings in the Case of the Anti-Soviet 'Bloc of Rights and Trotskyites'. Moscow: People's Commissariat of Justice of the USSR. 1938. p. 447.

- ^ Medvedev, Roy (1976). Let History Judge, The Origin and Consequences of Stalinism. Nottingham: Spokesman. p. 181. ISBN 0-85124-150-6.

- ^ Parrish, Michael (1996). "The Orel Massacres, the Killings of Senior Military Officers". The Lesser Terror: Soviet State Security, 1939-1953. Westport, CT: Praeger. pp. 69–109. ISBN 0275951138.

%252C_Emblem_of_Russia_(1991%E2%80%931992).svg.png)