Turkish–Azeri blockade of Armenia (1989–present)

| Turkish–Azeri Blockade of Armenia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict | |||

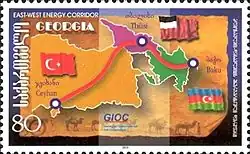

Top: A Georgian stamp commemorating the Azeri–Georgian–Turkish pipeline which notably bypasses Armenia. Bottom: The Armenian–Turkish border which has been closed since 1993. | |||

| Date | July 16, 1989 | ||

| Location | |||

| Goals |

| ||

| Methods | |||

| Resulted in | |||

| Parties | |||

The joint Turkish–Azeri blockade of Armenia is an ongoing transportation and economic embargo against Armenia which has significantly impacted its economy and the regional trade dynamics of the Caucasus. The blockade was initiated in 1989 by Azerbaijan, originally in response to the Karabakh movement which called for independence from Azerbaijan and reunification with Armenia. Turkey later joined the blockade against Armenia in 1993. The blockade aims at isolating Armenia (and Nagorno-Karabakh until 2023) to pressure the Armenian side to make concessions:[9][10][11] namely, the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in Azerbaijan’s favor, the cessation of Armenia's pursuit of international recognition of Turkey’s genocide in Western Armenia, the ratification by Armenia of the 1921 borders inherited from the Kemalist-Soviet Treaty of Kars,[a] and the establishment of an extraterritorial corridor through Armenian territory.

This dual blockade led to acute shortages of essential goods,[12] an energy crisis, unemployment,[7] emigration,[13][14][15] ecological damage,[16] and widespread poverty in Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh, while also hindering economic development and international trade. The blockade prevents the movement of supplies and people between Armenia, Turkey, and Azerbaijan and has isolated the Armenian side for 30 years;[17] however, with the exception of the Kars-Gyumri railway crossing, the Turkish–Armenian border had already been closed since the 1920s[18] and is sometimes described as the last vestige of the Iron Curtain.[19][20][21] Despite the initial devastating effects of the blockade, Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh were dubbed the "Caucasian Tiger,"[22][23] for their significant economic growth, particularly in the early 2000s; however, poverty remains widespread in Armenia with economic growth remaining heavily reliant on external investments.[24][25][26]

Between 2022 and 2023, Azerbaijan escalated its blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh by closing the Lachin corridor using a military checkpoint, sabotaging civilian infrastructure,[27][28][29][30] and attacking agricultural workers.[31][32][33][34] The ten-month-long military siege of the region isolated it from the outside world[35][36][37] and produced a humanitarian crisis that was widely considered to be genocidal by experts and human rights advocates.[38][39][40] In 2023, Azerbaijan used military force to take control over Nagorno-Karabakh, resulting in the flight of the entire population to Armenia.

Despite international pressure to lift the blockade,[41][42][43] and Azerbaijan's military resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, Turkey and Azerbaijan continue to keep their borders closed to Armenia.[44] With these two countries accounting for half of Armenia’s four neighbors,[45] 84% of Armenia’s international borders remain closed,[46][47][46][48] making the landlocked country extremely dependent on Russia and limited trade with Georgia and Iran.[13][49][50][51][47][52]

History

Timeline

1989

- Azerbaijan initiates a rail blockade in response to the Karabakh movement, cutting off food and fuel deliveries to Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.

1990

- January – Anti-Armenian violence in Azerbaijan escalates, resulting in pogroms in Sumgait, Baku, and elsewhere, and Azerbaijan imposes the blockade on all of Armenia.

1992

- Armenian militia of Nagorno-Karabakh capture Lachin during the Karabakh Movement and ensuing First Nagorno-Karabakh War, ending a three-year isolation and establishing a humanitarian corridor to Armenia.

- U.S. Congress passes Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act, prohibiting direct aid to Azerbaijan until the blockade is lifted.

1993

- April – Turkey joins Azerbaijan in the blockade, closing its airspace to Armenia as well as its land border and stationed troops on the Armenia-Turkey border.

- July – Azeri saboteurs repeatedly bomb gas pipelines supplying Armenia through Georgia, exacerbating the crisis.

1994

- The blockade forces Armenia to reconsider restarting the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant despite safety concerns due to the energy crisis.

1995

- Under U.S. pressure, Turkey resumes air transit for humanitarian aid to Armenia but keeps its land border closed.

2008

- The Russo-Georgian War disrupts Armenia’s primary trade route through Georgia, worsening the impact of the blockade.

2022

- Azerbaijan escalates its blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh by closing the Lachin Corridor using a military checkpoint, producing a humanitarian crisis in the Armenian enclave.

2023

- The Turkish–Armenian border is temporarily opened for the first time in 35 years to allow humanitarian aid from Armenia to earthquake victims in Turkey.

- Azerbaijan seizes Nagorno-Karabakh in a military operation, resulting in the flight of the entire population to Armenia proper.

- Armenia proposes the Crossroads of Peace project which aims to restore transportation links

2025

- The United States brokers the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP), which involves an exclusive 99 year lease for an American-led consortium to mediate movement through a corridor on sovereign Armenian territory.[53]

History

Azerbaijan started the blockade in September 1989 in response to the Karabakh movement which called for the reunification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia.[54]

The Azerbaijan Popular Front, later assisted by Azeri irregular militias and troops, initiated a rail blockade, cutting off food and fuel deliveries to Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.[55][56] The blockade disrupted Armenia's economy and strained its resources, with significant impacts on everyday life and infrastructure, triggering a national emergency.[57] The effects were made worse by the 1988 earthquake and the collapse of the internal trading system of the USSR.[58] This initial action was compounded by anti-Armenian violence in Baku and Sumgait in January 1990. As the conflict intensified, Azerbaijan extended the blockade to all of Armenia, which relied heavily on imports that passed through Azerbaijani territory. Armenian fedayi subsequently raided arsenals and police stations in preparation to defend Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.[59]

In 1991, the population of Nagorno-Karabakh voted for independence in a referendum, resulting in Azerbaijan attempting to revoke its autonomy and sieging its capital for six months. In early 1992, Armenia and Iran signed a series of economic agreements, leading to the construction of a temporary bridge over the Arax River, which was considered a lifeline for Armenia,[58][45] In May 1992, local Armenian militia in Nagorno-Karabakh captured Lachin, ending the region’s complete 3-year-long isolation[60] and established a humanitarian corridor to Armenia.[61][62][63]

In 1992, the U.S. Congress passed legislation to pressure Azerbaijan to lift the blockade against Armenia. Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act prohibited direct government aid to the Azerbaijani government, until it “ceased all blockades and other offensive uses of force against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh."

In the harsh winter of 1992, Turkey hesitantly agreed to ship wheat to Armenia promised from the European community but at a very slow pace and at exorbitant prices.[2]

After many Byzantine tactics and several months of delay, Turkey finally agreed to send the 100,000 tons of wheat which the European community had promised to replace. After having humiliated the entire population of Armenia in bread queues, Turkey finally began to ship the wheat across the border in a very slow pace and to an extremely high price The transport of wheat, all the way from Russia to Armenia, cost only two dollars per ton, payable in deprecated rubles Turkey charged $56 per ton in hard currency Armenia was forced to empty its reserves of foreign currency in order to avoid a bread riot). There were many similar actions where Ankara forced the Armenian civil aircraft down on Turkish soil and delayed the humanitarian aid for several months.

Later in 1993, with the aim to assist Azerbaijan, Turkey joined Azerbaijan in imposing a land and air blockade on Armenia and stationed troops on the Armenian-Turkish border.[65][66][67] That same year Azeri saboteurs exacerbated the crisis by repeatedly bombing the remaining gas pipelines[68][69] supplying Armenia through Georgia[70][71][72][73] and attacking Armenian locomotive crews.[74] Georgia did not investigate these acts of terrorism and was believed to steal fuel destined for Armenia that came from Turkmenistan.[75]

A second pipeline from Iran via Azerbaijan was also damaged in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War and as of 2006 was still not operational.[72] In 1991 pressure to restart the Metsamor power plant increased after a natural gas pipeline from Turkmenistan was severed due to the blockade.[76] Local scientists originally condemned the decision to reopen the plant, describing it as a "potential Chernobyl."[77]

Turkey also halted the air transit of foreign humanitarian aid and shipments destined towards Armenia[67][78][79] but eventually changed this policy in 1995 due to pressure from the United States.[80] In 1995, Armenia agreed to exclude genocide recognition to normalize Turkish–Armenian relations, if Turkey excluded Nagorno-Karabakh.[81]

The 2008 Georgian-Russian War was a significant shock to the Armenian economy, as the country's foreign trade primarily relies on routes passing through Georgia due to the Azerbaijani-Turkish blockade.[82][83] During the week-long Georgian-Russian war, the import of fuel and grain through Georgia into Armenia virtually stopped.[84]

Between 2022 and 2023, Azerbaijan escalated its blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh by closing the Lachin Corridor, resulting in the region’s complete isolation from Armenia and the outside world. This isolation ended in 2023 when Azerbaijan seized the region during a military offensive, resulting in the flight of the entire population. The blockade of Armenia proper by Turkey and Azerbaijan continues to this day.

Aims and Impact

The governments of Turkey and Azerbaijan have demanded the following concessions for lifting the blockade;

- The resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in Azerbaijan’s favor,

- Armenia’s withdrawal of international recognition of Turkey’s genocide in Western Armenia,

- Armenia’s ratification of the 1921 Turkish–Armenian borders[b] it inherited from the Kemalist-Soviet Treaty of Kars,

- An extraterritorial corridor through Armenia.[67][85][86]

Multiple sources, including human rights advocates and locals,[87] have stated that the blockade aims to eliminate the remaining Armenian population in the Armenian Highlands.[88][89][90] During the Armenian Genocide, Turkey also blockaded Armenia in 1918, preventing the influx of food supplies, leading to a famine and epidemics.[91] Being a landlocked country, Armenia is very susceptible to blockades as a form of political coercion.[92]

The ongoing blockade and the ensuing energy crisis led to large effects on Armenia’s environment, economy and civil society. Donald Miller and Lorna Touryan state that Armenians were "reduced to living like their medieval ancestors" due to the deprivations imposed on society.[93]

Humanitarian impact

The blockade had a devastating humanitarian impact on Armenia, exacerbating the effects of the 1988 earthquake and leading to severe shortages in essential supplies.[94][75] By 1993, an estimated 90–95% of the population was living below the poverty line.[95][96] Hospitals struggled to function due to acute shortages of electricity, heat, and medical supplies, which led to many ceasing operations. Bread was rationed daily to 200-250 grams per person.[97][98] The decline in living standards led to between 17% and 30% of Armenia's population emigrating.[14][99][15][100][100]

Public transportation ceased or became prohibitively expensive[93] and schools were closed.[98] Electricity in Yerevan was available for only two hours a day, which raised the risk of freezing or starvation.[70][72] Trees on hospital grounds were cut in order to provide wood for burning to keeping hospitals warm.[101] By 1993, over half of the hospitals in Armenia had stopped operating because they lacked essential resources, leading to the deaths of healthy infants due to the cold and inadequate equipment.[95]

The medical crisis worsened, with supplies of basic items like surgical gloves, syringes, and chlorine for water purification becoming unreliable by 1992.[102] This vulnerability particularly affected the elderly and newborns, causing rapid declines in the level of medical care.[102] The blockade disrupted earthquake reconstruction efforts and further impoverished Armenian refugees from Azerbaijan, highlighting the critical role of humanitarian aid, primarily from the United States, in Armenia's survival during the early 1990s.

The blockade substantially increases actual travel distances and transportation costs. For instance, the journey from Yerevan to the Turkish border town of Igdir is extended tenfold because traffic must detour through Georgia due to the closed border.[103]

Impact on Armenia's civil society

The historian Peter Rutland states, "The need to unify and protect the Armenian nation was the driving force that persuaded diverse social groups within Armenia to sink their differences and cooperate against the common foe. However, this consensus came at a huge price: years of economic blockade and armed struggle. There is a great danger that the strains arising from the conflict with Azerbaijan will undermine the fragile consensus that launched Armenian democracy."[56]

Alla Mirzoyan states that "The damage caused by the blockade is both material and psychological", noting that it has created a siege mentality,[47] and reinforces the historical narrative of joint Turkish–Azeri policy to isolate Armenia.[104] Multiple sources consider the blockade to be a violation of the Treaty of Kars, which calls for "free transit of persons and commodities without any hindrance" among the signatories and that the parties would take "all the measures necessary to maintain and develop as quickly as possible railway, telegraphic, and other communications."[105][106][107] David Davidian, a journalist and lecturer, states that the blockade of Armenia constitutes "a two decades long violation of the Treaty of Kars by half of its signatories."[107]

Following independence, the Armenian government under Ter-Petrosyan aspired to improve diplomatic relations with Turkey, despite the ongoing historical legacy of the Armenian Genocide.[108][109] However, according to the economist Eduard Agajanov, this position later changed. In 2005, Agajanov asserted that the need to reopen the borders was downplayed in order to "to preserve the current oligarchic economic system in Armenia, which cannot survive if the borders are opened and competition with Turkish goods becomes tougher."[110][111] The historian Vahagn Avedian states "the Armenian political leadership exploited the animosity from Turkey and Azerbaijan which has stifled democratic development and restrained opposition, fearing that internal unrest could be exploited by Azerbaijan in the Karabakh conflict."[112] He states that this has "amplified the well-known Armenian proverb, 'Rather our sick lamb than the enemy’s healthy wolf,' a lesson of two millennia of statehood, balancing in a geopolitical position jammed between superpowers."[112]

Economic impact

The blockade severely stunted Armenia's economic development,[113][114] with over 80% of the country's borders closed for more than 30 years.[115][116] Up until the blockade, 85% of Armenia’s goods and 80% of its energy was supplied through Azerbaijan.[117][118] The ensuing energy crisis produced by the blockade produced massive layoffs[119][92][13] and other enduring effects: economic studies in the early 2000s concluded that the blockade cost the Armenian economy 30–40% of its national productivity,[120][121] and ten years after the 1988 Spitak earthquake 17,500 people were still living in temporary housing in Gyumri.[92]

The blockade immediately triggered a severe four-year-long energy crisis and forced Armenia to reconsider using the Metsamor nuclear power plant despite safety concerns.[122][95][123][58][123] The blockade also increased transportation costs for goods[124] and gives Georgia a near-monopoly position over Armenia.[125][126]

The economic growth of Armenia was crippled after 1989 by the blockade of fuel and other materials, and nearly all energy was supplied from abroad, causing shortages under the early 1990s blockade. Natural gas delivery from Turkmenistan via the Georgia pipeline was frequently blocked, contributing to chronic fuel shortages.[95] By the winter of 1994–1995, social unrest was fueled by these shortages, and a new fuel agreement with Georgia and Turkmenistan provided slight relief, increasing the daily electricity ration from one hour to two hours. However, long-term increases in fuel depended on further negotiations and Armenia's ability to pay its substantial debt to Turkmenistan.[102]

The closure of the Turkish–Armenian border in April 1993 had significant economic repercussions, with unemployment and poverty remaining widespread due to the ongoing trade blockade imposed by Turkey and Azerbaijan. A reopening of the border could benefit Armenia's economy, despite potential competition from external markets, and would also benefit Turkey's economically depressed eastern regions.[127][128][129][130] The impact of the blockade remains significant and contribute to Armenia's ongoing economic difficulties and complicate its integration into regional economic systems.[131]

Environmental impact

The blockade forced reliance on unsustainable practices like widespread deforestation and intensive agriculture, led to risky energy solutions such as the potential reactivation of a nuclear power plant, and necessitated the reopening of polluting industries. These actions were undertaken to mitigate the immediate hardships imposed by the blockade but posed significant long-term risks to environmental health and ecological balance.

One significant consequence has been widespread deforestation,[132] as the blockade cut off fuel supplies, forcing people to rely heavily on wood for heating and cooking during harsh winters. This deforestation has led to soil erosion, loss of biodiversity, and increased vulnerability to natural disasters such as landslides.

Additionally, the energy crisis prompted the government to consider restarting the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant, which had been shut down due to earthquake risks, thereby raising concerns about potential nuclear hazards. Armenian Environmental Committee Chairman Samuel Shahinian explained the decision: "Our people are so cold we cannot explain anything to them, they just want to be warm."[133] Further safety concerns arose when it was revealed that the ongoing blockade of the country by its neighbours Turkey and Azerbaijan meant that nuclear fuel for the plant was flown onboard Antonov and Tupolev airplanes from Russia into Yerevan Airport in secret shipments which Alexis Louber, Head of the EU delegation in Yerevan, likened to "flying around a potential nuclear bomb."[134]

The blockade also severely affected water resources. Lake Sevan, Armenia's largest freshwater body, experienced significant water level drops due to increased reliance on hydroelectric power to compensate for the energy shortfall.[135][98] This drawdown for irrigation and energy purposes threatened the lake's ecosystem, endangering its flora and fauna.[136]

Furthermore, the blockade's economic strain forced Armenia to reopen highly polluting industries like the Nairit Chemical Plant, which had been closed in the previous year due to their environmental impact.[137]

Geopolitical impact

The blockade has hampered Armenia's inclusion in regional infrastructure projects and promoted its economic and security dependence on Russia.[138][139][140][141] Except with Georgia, all international railway links between Armenia and its neighbors have been closed since 1993 due to the blockade against the country by Turkey and Azerbaijan.[142][143]

The blockade and Turkish government's ongoing denial of the genocide have been cited as significant barriers to Turkey's membership into the European Union.[144] In its attempt to isolate Nagorno-Karabakh, the Azerbaijani government blacklists humanitarian organizations and journalists who worked in the region.[145][146] The only international organizations who continued to work in Nagorno-Karabakh were HALO and the ICRC.[147][148] The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, Reporters Without Borders, and the International Federation of Journalists, have called on Azerbaijan to allow entry of independent organizations, including United Nations agencies.[149][150][151][152]

As a result of the blockade, Armenia must depend on unreliable supply routes with Georgia and Iran for trade and humanitarian assistance.[153] The border between Armenia and Georgia is crucial because international sanctions restrict trade with Iran, and Armenia's trade with Russia, its main trade partner, relies on transit through Georgia. Approximately 70% of Armenia’s foreign trade go through Georgia:[154] however, seasonal weather conditions affecting the Verkhniy Lars border crossing and inconsistent ferry services from Georgia’s Black Sea ports limit Armenian goods’ access to international markets.[155] Armenia's exclusion from major regional projects is evident in its absence from the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline, the South Caucasus Gas Pipeline, and the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway network, which have been instrumental in boosting connectivity and economic integration in the South Caucasus.[156]

To mitigate its isolation, Armenia has sought to enhance its connectivity through alternative routes. Notably, Armenia has been in discussions with India to use Iran's Chabahar Port to boost trade and connectivity. This port offers Armenia access to the Indian Ocean and broader markets in Central Asia and India, which is seen as a crucial step to overcome the limitations imposed by the blockade.[157][116] However, the border with Iran is problematic due to the sanctions it faces.[116][158]

Turkey’s decision to join Azerbaijan in the blockade spurred Armenia to approve a security agreement in 1994 with Russia that stations Russian forces at the Armenian-Turkish border.[159] The Metsamor nuclear power plant which supplies Armenia with 30% of its energy requires fuel that is flown in from Russia, due to the land blockade.[160]

Armenian officials have openly stated that the decision to join the Eurasian Economic Union was forced by economic and security concerns, citing the blockade as a factor.[161]

Trade between Armenia and Turkey is also imbalanced, with the Armenian market being fully accessible to Turkish goods while Turkey remains almost entirely closed to Armenian imports.[162]

Developments

Despite international efforts to lift the blockade, it remains in place. The UN, EU, and the OSCE have repeatedly called for an end to the blockade, linking the normalization of relations between Turkey and Armenia to Turkey's EU accession. In 2009, the Armenian and Turkish governments signed the Zurich Protocols to establish diplomatic relations and lift the blockade. In the protocols, Armenia met two of Turkeys preconditions, including halting international recognition of Turkey’s genocide against Armenians and approval of the Treaty of Kars.[163][164] However, pressure from Azerbaijan's authorities[165][166] and oil investment,[167][168] as well as domestic pressure from nationalistic voters,[167] led to Turkey not ratifying the protocols.[169][170]

Recent discussions have highlighted the potential economic benefits of reopening the border. A study by the Amberd Research Center suggested that lifting the blockade could increase Turkish exports to Armenia by 65% and Armenian exports to Turkey by 42%.[171] However, the political landscape and historical grievances continue to hinder progress. Initiatives to normalize relations have repeatedly failed due to additional preconditions set by Turkey and Azerbaijan, including the settlement of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict in Azerbaijan’s favor, the withdrawal of international recognition of the Armenian Genocide, and Armenia’s concession of an extraterritorial corridor through Armenian territory.[166]

On February 11, 2023, the Turkish–Armenian border was temporarily opened for the first time in 35 years, to let humanitarian aid from Armenia reach victims of a major earthquake in Turkey.[172][173]

International reactions

The international community – including the UN Security Council,[41] the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe,[174] EU, and human rights organizations[97][175] – has urged the lifting of the blockade.[42][43] The embargo and accompanying concessions demanded by Azerbaijan and Turkey meet the criteria of blockade under international law.[176] The Soviet Russian Republic at the time also petitioned Azerbaijan to lift the blockade.[177]

Armenia received humanitarian supplies from the USA[178] and Syria.[179] In 1992, the USA passed legislation which banned direct U.S. aid to Azerbaijan to pressure Baku to lift its blockade on Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh.[180][170] Section 907 of the Freedom Support Act specifically excludes Azerbaijan from receiving U.S. assistance until it ceases all blockades and other offensive uses of force against Armenia and Nagorno-Karabakh; however, since 2002, the US government has consistently waived Section 907[181] and provided military funding to Azerbaijan.[182][170] Political analysts, Sam Brownback and Michael Rubin, say that the US should enforce the Humanitarian Corridors Act,[183][184][185] which bans US aid to countries such as Turkey that prevented the delivery of US humanitarian assistance.[186][170] Michael Rubin also states that Turkey’s ongoing blockade of Armenia violates the 1921 Treaty of Moscow.[187] Soviet physicist and human rights advocate, Andrei Sakharov, called for an air bridge, arguing the international community had a duty to uphold the 1948 Geneva Conventions, which prohibit blockades against peaceful countries.[188]

Political observers have criticized the US decision to waive or not enforce these acts, suggesting that US policy has abetted Azerbaijan's actions.[189][190][191] David Phillips, political scientist at Columbia University's Institute for the Study of Human Rights, stated in 2020 that it was unlikely that the US government would end its assistance to Azerbaijan: noting that the US had provided $120 million military assistance to Azerbaijan between 2018 and 2020, and that President Donald Trump received money from licensing agreements in Turkey and money from Azerbaijani oligarchs.[170]

The European Parliament has condemned the blockade and called on Turkey to normalize relations with Armenia, reaffirming its recognition of the Armenian Genocide.[192] In 2004, the European Parliament urged Turkey to lift its blockade against Armenia as part of its European ambitions. The EU has made the normalization of Armenian-Turkish relations a precondition for Turkey's accession to the EU.[193]

Christian Solidarity International wrote that "the blockade of Armenia is a new form of racism: its people are being subjected to great suffering because they are of the same nationality as the people of Karabakh who are fighting for their independence."[97] Archbishop Mesrob Ashjian stated that Azerbaijan’s continuation of the blockade amidst 1988 earthquake reconstruction efforts, reveals deeper motives than just nationalism: "It is an attempt, first, to annihilate the Christian minority in Azerbaijan."[194]

Turkey

Turkey has demanded certain conditions for normalizing relations with Armenia, initially the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict in Azerbaijan's favor, and later added other conditions: the withdrawal of international recognition of the Armenian Genocide, and Armenia's ratification of the borders established in the 1921 Treaty of Kars, and an extraterritorial corridor between Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan. In contrast, Armenia has consistently advocated for establishing diplomatic relations with Turkey and reopening the border without any preconditions.[195][196][197]

The Turkish blockade of the Armenian border and the government's ongoing policy of genocide denial have also been cited as barriers to Turkey's membership into the European Union.[198][199] A 2004 draft of the European Parliament's report on Turkey's accession bid urged the country to open its borders with Armenia, foster good-neighbor relations, and "give up any action impeding the reconciliation of the two countries."[199]

Armenia’s declaration of independence from the USSR calls for recognition of the 1915 Genocide in Ottoman Turkey and Western Armenia,[200][201] which includes the Kars province. In 2007, the head of the Turkish parliament's foreign affairs committee, stated that the passage of the US resolution recognizing Turkey’s genocide of Armenians would have consequences for Armenia, leading Ankara to maintain its blockade.[202] In addition to closing its land border with Armenia, Turkey has also denied passage through its airspace to planes bound for Armenia on a number of occasions.[1][2]

Armenia

Armenia condemns the blockade imposed by Turkey and Azerbaijan, considering it a severe economic, geopolitical, and existential threat.[203][204][205] In 1990, Armenians criticized the Soviet Army for not stopping the blockade and not preventing the ensuing Baku pogroms.[206]

Armenia has also challenged the legality of Turkey's border closure, stating that Ankara’s actions violate the Kars Treaty,[207] the World Trade Organization's (WTO) free trade agreements, the UN Millennium Development Goals, and various international laws that ensure landlocked countries have access to the sea.[208]

Specifically, Article XVII of the Kars Treaty calls for the "free transit of persons and commodities without any hindrance" among the signatories and that the parties would take "all the measures necessary to maintain and develop as quickly as possible railway, telegraphic, and other communications."[209][207] In contrast, ARF, a political party in Armenia and in the diaspora overtly rejects the Treaty of Kars and states that because the three Transcaucasian Republics were under the control of Moscow in 1921, their independent consent was questionable.[210][210]

Despite Armenia’s accusations that Turkey has violated the Kars Treaty, Armenia continues to affirm its acceptance of the current border, with government officials stating that the country acknowledges the Treaty of Kars and the existing border, as well as the commitments established by the treaty. Armenia has avoided making official declarations about the Treaty of Kars asserting that this issue should be addressed as part of broader negotiations between the two nations rather than as a prerequisite for talks.[211]

Armenia has consistently advocated for establishing diplomatic relations and reopening the Turkish–Armenian border without any preconditions.[212][213] Following the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War, Armenia agreed that multiple routes be opened simultaneously that connect Armenia to Turkey and Azerbaijan.[214][215][215] In contrast, Azerbaijan and Turkey[216] have insisted on an extraterritorial corridor exclusively between Azerbaijan and its exclave of Nakhchivan.[217] In 1995, Armenia agreed to exclude genocide recognition to normalize Turkish–Armenian relations, if Turkey excluded Nagorno-Karabakh.[81]

Azerbaijan

Azeri policy has been to force Armenians to choose "prosperity without Karabakh or poverty with Karabakh,"[218][116][1] by excluding Armenia from regional infrastructure projects[219] and petitioned its trading partners Georgia and Turkey to maintain pressure on Armenia.[220] Azerbaijan has stated that the fossil fuels it sells to Georgia should be exclusively for Georgia's use, warning that any re-sale to unauthorized third parties could lead to potential sanctions.[220]

Azerbaijan has also repeatedly opposed the normalization of diplomatic relations between Turkey and Armenia.[221][222][223] Analysts state that the reopening of the Turkish–Armenian border may be contingent on Azerbaijan's leadership, due to Azerbaijan's oil investments in Turkey.[168][167] Azerbaijan's state-owned SOCAR energy company is Turkey's biggest foreign investor.[168]

In 2004, Azerbaijan threatened to withdraw from peace talks with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh if Turkey opened its border with Armenia; the Azeri Parliament Speaker stated "If Turkey opens the border with Armenia, it will deal a blow not only to Azerbaijani-Turkish friendship but also to the entire Turkic world."[224]

When Armenian-Turkish relations were thawing under the agreed 2009 Zurich Protocols, Azerbaijan stated that the relationship "cast a shadow over the spirit of brotherly relations" between Azerbaijan and Turkey, which prompted Turkey to halt the process.[216] Azerbaijan has also threatened to seize internationally recognized Armenian territory by force from if it does not concede an extraterritorial corridor to Azerbaijan.[225]

Analysis

Overall, the blockade and the pressure for Armenia to concede a corridor through its country are seen as part of a broader strategy by Turkey and Azerbaijan to isolate Armenia[226] and force it into geopolitical subservience,[227][228][229] while also pursuing their own regional ambitions.[230] The journalist Uzay Bulut asserts that Turkey and Azerbaijan still oppose Armenia with blockades and other means because Armenia's independence opposes Pan-Turkic interests, despite Azerbaijan's military resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.[231] Former Turkish parliamentarian Garo Paylan states that "both Erdoğan and Aliyev benefit from having artificial or imagined enemies" and therefore are hesitant in making peace with Armenia and opening the border.[232]

In 2013, the historian Vahagn Avedian stated that despite Azerbaijan’s alleged calls for a peaceful resolution, Azerbaijan’s statements and policies indicate that the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict could only be resolved through the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh or through a legally recognized referendum in the region.[233]

The historian Richard G. Hovannisian drew parallels between the suffering created by the blockade and the deportations of Armenians during the 1915 genocide, stating that "Once again, the forced starvation of hundreds of thousands of Armenians in 1915 became a vivid experience for the besieged people of Mountainous Karabagh and Armenia."[234] These parallels have also been drawn by Armenians,[92] as well as other political observers.[187] A group of prominent scholars and political leaders published a letter in The New York Times in which it urged Soviet authorities and the international community to lift the blockade—describing it as the "strangulation of Armenia"—and ensure the safety of Armenians in the Caucasus, noting the wave of anti-Armenian violence and pogroms in Azerbaijan.[235]

See also

Notes

- ^ Following Turkey's invasion of Armenia in 1920, the Democratic Republic of Armenia signed the Treaty of Alexandropol under duress, effectively accepting Turkish territorial demands. However, the treaty was never ratified by an independent post-Soviet Armenia.

- ^ Following Turkey's invasion of Armenia in 1920, the Democratic Republic of Armenia signed the Treaty of Alexandropol under duress, effectively accepting Turkish territorial demands. However, the treaty was never ratified by an independent post-Soviet Armenia.

References

- ^ a b c Avedian, Vahagn (2022-02-08), "Exploring the Normalization of Relations Between Armenia and Turkey", E-International Relations, retrieved 2024-08-30

- ^ a b c Avedian, Vahagn (2013). "Recognition, responsibility and reconciliation: the trinity of the Armenian genocide" (PDF). Europa Ethnica. 70 (70.3/4): 77–86. doi:10.24989/0014-2492-2013-34-77.

- ^

- Brent Hierman (2017). Russia and Eurasia 2017–2018. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-4758-3517-5.

- Bohlen, Celestine (1993-02-07), "Blockade and Winter Deepen Misery in Armenia", The New York Times, archived from the original on 2020-11-15, retrieved 2024-09-11,

Two weeks ago, the hospital's telephones went dead when Armenia's last functioning gas pipeline was damaged in an explosion attributed to Azerbaijani terrorists.

supplying Armenia through Georgia - Uhlig, Mark A. (1993). "The Karabakh War". World Policy Journal. 10 (4): 47–52. ISSN 0740-2775. JSTOR 40209334.

- Curtis, Glenn E. (Glenn Eldon) (1995). "Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia : country studies". (No Title). Area handbook series.

- Stanton, Elizabeth A.; Ackerman, Frank; Resende, Flávia (2009). The Socio-Economic Impact of Climate Change in Armenia (PDF) (Report). Somerville, MA: Stockholm Environment Institute – U.S. Center, Tufts University. Retrieved 2024-08-23.

- "Armenia TED Case Study", gurukul.ucc.american.edu, archived from the original on 2017-02-27, retrieved 2024-09-03 and attacking Armenian locomotive crews

- Nadein-Raevski, V. (1992-01-01), "The Azerbaijani Armenian Conflict: Possible Paths towards Resolution", Ethnicity and Conflict in a Post-Communist World, Palgrave Macmillan UK, p. 124, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-22213-1_7, ISBN 978-1-349-22215-5, archived from the original on 2018-06-15, retrieved 2024-08-23 Georgia did not investigate these acts of terrorism and was believed to steal fuel destined for Armenia that came from Turkmenistan

- Vardanian, Astghik; Berndt, Jerry (July 1996). "Armenia's Choice". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 52 (4): 50–54. Bibcode:1996BuAtS..52d..50V. doi:10.1080/00963402.1996.11456644. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^

-

- Caroline Cox, John Eibner (1993). Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh. Institute for Religious Minorities in the Islamic World, 1993. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-3-9520345-2-1.

- Bohlen, Celestine (1993-02-07), "Blockade and Winter Deepen Misery in Armenia", The New York Times, retrieved 2024-09-11

- Times, Los (1993-01-24), "Explosion of pipeline plunges Armenia into cold and dark", baltimoresun.com, archived from the original on 2023-09-01, retrieved 2024-08-26

- Vardanian, Astghik; Berndt, Jerry (July 1996). "Armenia's Choice". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 52 (4): 50–54. Bibcode:1996BuAtS..52d..50V. doi:10.1080/00963402.1996.11456644. ISSN 0096-3402.

- Curtis, Glenn (1995), Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia : country studies, D.C.: Federal Research Division, retrieved 2024-08-22

-

- ^ Bohlen, Celestine (1993-02-07), "Blockade and Winter Deepen Misery in Armenia", The New York Times, archived from the original on 2014-04-24, retrieved 2024-09-11,

Cut off from its traditional sources of natural gas, much of which flowed through Azerbaijan, Armenia went through its first energy crisis last winter, when the Government closed schools and factories and rationed heat and electricity to keep the population going.

- ^

- "Armenia's Isolation Grows Only Deeper", The New York Times, 2004-12-26, retrieved 2024-09-11,

The limited opportunities have contributed to an exodus of working-age Armenians since independence 13 years ago, with some estimates putting the population loss at nearly 30 percent.

- Jerry L. Johnson (2000). Crossing Borders—confronting History Intercultural Adjustment in a Post-Cold War World. University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-1536-8.

The destabilizing exodus of some 800,000 educated and resourceful Armenians, mostly young people, occurred at a time when they were needed the most for nation-building.

- "Armenia | Caucasus, Soviet Union, Genocide", Encyclopedia Britannica, archived from the original on 2024-08-10, retrieved 2024-08-21,

A blockade imposed by Azerbaijan in 1989 had devastated the Armenian economy; the resulting severe decline in living conditions led hundreds of thousands of Armenians to emigrate.

- "Armenia's Isolation Grows Only Deeper", The New York Times, 2004-12-26, retrieved 2024-09-11,

- ^ a b

-

- Ohanyan, Anna; Broers, Laurence (2020). Armenia's Velvet Revolution Authoritarian Decline and Civil Resistance in a Multipolar World. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-78831-717-7.

Armenia's GDP dropped by 56 per cent in 1990-3, and half a million jobs - accounting for one third of all those employed - disappeared.

- Miller, Donald E.; Miller, Lorna Touryan; Berndt, Jerry (September 2003). Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780520234925.

- Vardanian, Astghik (1996-07-01), "Armenia's Choice", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 52 (4), Routledge: 50–54, Bibcode:1996BuAtS..52d..50V, doi:10.1080/00963402.1996.11456644,

And so the crisis began. Industiy slowed, factories shut down, and office workers were laid off. Even ambulance service was halted because of a lack of gasoline. People passed the winters in their apartments, where room temperatures hovered close to freezing. Deprived of their jobs, they had only two reasons to go out—to get fuel and food.

Alt URL - Bohlen, Celestine (1993-02-07). "Blockade and Winter Deepen Misery in Armenia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2020-11-15.

Most of the working population is on a prolonged furlough, at half pay.

- Paturyan, Yevgenya (2024). "Revolution, Covid-19, and War in Armenia: Impacts on Various Forms of Trust". Caucasus Survey. 13. Brill Schöningh: 2024. doi:10.30965/23761202-bja10036.

The economic blockade imposed on Armenia by Azerbaijan and Turkey further exacerbated the situation, leading to widespread poverty and unemployment.

- Ohanyan, Anna; Broers, Laurence (2020). Armenia's Velvet Revolution Authoritarian Decline and Civil Resistance in a Multipolar World. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-78831-717-7.

-

- ^

- Vardanian, Astghik (1996-07-01), "Armenia's Choice", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 52 (4), Routledge: 50–54, Bibcode:1996BuAtS..52d..50V, doi:10.1080/00963402.1996.11456644, retrieved 2024-08-27,

The Ministry of Ecology estimates that 800,000 trees were chopped down throughout the country in the first two Winters.

as the blockade cut off fuel supplies, forcing people to rely heavily on wood for heating and cooking during harsh winters. - Higgins, Andrew (1995-06-06), "Energy-starved Armenians risk a new Chernobyl", The Independent, retrieved 2024-08-27 Armenian Environmental Committee Chairman Samuel Shahinian explained: "Our people are so cold we cannot explain anything to them, they just want to be warm."

- Brown, Paul (2004-06-02). "EU halts aid to Armenia over quake-zone nuclear plant". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2009-05-01. Alexis Louber, Head of the EU delegation in Yerevan, likened secret nuclear fuel airlifts to "flying around a potential nuclear bomb."

- Shapiro, Margaret (1993-01-30), "Armenia's 'Good Life' Lost to Misery, Darkness, Cold", The Washington Post, retrieved 2024-08-27 describing the impact of the blockade on daily life.

- Bohlen, Celestine (1993-02-07), "Blockade and Winter Deepen Misery in Armenia", The New York Times, retrieved 2024-09-11 reporting severe winter hardships and infrastructure collapse.

- Suny, Ronald; E., Glenn (1995-01-01), Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia : country studies, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, pp. 28–34, retrieved 2024-08-21,

The large-scale felling of trees for fuel during the winters of the blockade has created another environmental crisis....The Ministry of the Environment reported that the lake's water level had dropped by fifty centimeters in 1993. Experts said that this drop brought the level to within twenty-seven centimeters of the critical point where flora and fauna would be endangered.

- Rutland, Peter (1994-01-01), "Democracy and nationalism in Armenia", Europe-Asia Studies, 46 (5), Taylor & Francis Group: 839–861, doi:10.1080/09668139408412202, retrieved 2024-08-27 noting the reopening of the Nairit Chemical Plant despite environmental concerns.

- Vardanian, Astghik (1996-07-01), "Armenia's Choice", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 52 (4), Routledge: 50–54, Bibcode:1996BuAtS..52d..50V, doi:10.1080/00963402.1996.11456644, retrieved 2024-08-27,

- ^ Jardine, Bradley. "With new railway, Turkey seeks to isolate Armenia and integrate Azerbaijan". Eurasianet. Columbia University. Archived from the original on 2024-04-18. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ^ Avedian, Vahagn (2013-10-31). "The Unsustainable European Policy towards the South Caucasus". Foreign Policy Journal. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

The outspoken Azeri policy (in conjunction with the Turkish embargo) is to force Armenians to choose "prosperity without Karabakh or poverty with Karabakh," pushing Armenia to the degree of destitution that "people will even stop thinking about Karabakh." This has been confirmed on numerous occasions by President Aliyev himself, the latest from October 7, 2013: 'We must further keep Armenia isolated from diplomatic, political, economic, regional initiatives.' The same applies to the Turkish policy, which, in addition to the Karabakh dispute, also aims at the issue of forcing Armenia to drop its efforts for an international recognition of the 1915 Armenian genocide.

- ^ Ter-Matevosyan, Vahram (2017-05-04). "Armenia in the Eurasian Economic Union: reasons for joining and its consequences". Eurasian Geography and Economics. 58 (3). Routledge: 340–360. doi:10.1080/15387216.2017.1360193. Archived from the original on 2023-11-18. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

By inventing a "one nation, two states" formula, the leaders of Turkey and Azerbaijan have worked closely since the early 1990s to marginalize Armenia from regional energy and communication Projects.

- ^ Zinner, Ellen S.; Williams, Mary Beth (2013). When A Community Weeps Case Studies In Group Survivorship. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-87630-953-7.

This blockade began in 1988, preventing 80% of goods destined to Armenia from entering that country.

- ^ a b c Vardanian, Astghik (1996-07-01), "Armenia's Choice", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 52 (4), Routledge: 50–54, Bibcode:1996BuAtS..52d..50V, doi:10.1080/00963402.1996.11456644, retrieved 2024-08-21,

According to the U.N. Development Program, 676,000 people—or about one fifth of the population—left during this period, mainly settling in Russia, the United States, or Israel.

- ^ a b Chaloyan, Astghik (2017). Fluctuating Transnationalism Social Formation and Reproduction among Armenians in Germany. Springer. p. 65. ISBN 978-3-658-18826-9.

Roughly calculated, this wave can be determined from 1991 until 1995. According to CRRC (the Caucasus Research Resource Centres)...more than 17% of Armenia's population migrated between the years of 1991-1995...

- ^ a b Jerry L. Johnson (2000). Crossing Borders—confronting History Intercultural Adjustment in a Post-Cold War World. University Press of America. ISBN 0-7618-1536-8.

The destabilizing exodus of some 800,000 educated and resourceful Armenians, mostly young people, occurred at a time when they were needed the most for nation-building.

- ^ Suny, Ronald; E., Glenn (1995-01-01), Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia : country studies, Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, p. 28, retrieved 2024-08-21,

The large-scale felling of trees for fuel during the winters of the blockade has created another environmental crisis....The Ministry of the Environment reported that the lake's water level had dropped by fifty centimeters in 1993. Experts said that this drop brought the level to within twenty-seven centimeters of the critical point where flora and fauna would be endangered.

- ^ "Averting a New War between Armenia and Azerbaijan". Crisis Group. 2023-01-30. Archived from the original on 2024-07-05. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ^ Cheterian, Vicken (2017-01-02). "The Last Closed Border of the Cold War: Turkey-Armenia". Journal of Borderlands Studies. 32 (1): 71–90. doi:10.1080/08865655.2016.1226927. ISSN 0886-5655.

- ^ "Unprecedented progress". Deutsche Welle. 9 September 2009. Retrieved 2024-09-16.

- ^ Parsons, Robert (2012-02-02). "1915 Massacre Under Spotlight". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2024-09-16.

- ^ "Armenia-Turkey". Eurasian Partnership Foundation. Retrieved 2024-09-16.

- ^ The Caucasian Tiger: Sustaining Economic Growth in Armenia. World Bank Publications. 2007. ISBN 978-0-8213-6812-1. Retrieved September 18, 2024 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Nagorno-Karabakh's militarised social democracy". openDemocracy. Retrieved 2024-09-18.

- ^ "Armenia a Model for Developing Nations", Bloomberg, 2007-10-23, retrieved 2024-09-18

- ^ Punsmann, Burcu Gültekin, et al. "Review of isolation policies within and around the South Caucasus." Journal of Conflict Transformation (Caucasus Edition) 18 (2016). "At the same time, the two-digit economic growth in the early 2000s, largely due to the development of the construction sector, earned Armenia even the title of the 'Caucasian Tiger', vindicating Kocharyan’s approach. However, Kocharyan and his entourage understood very well, that this was more a ‘paper tiger’ and that without opening the borders, Armenia’s economy would not be able to sustain its growth."

- ^ "A "Tiger" Is Born in 15 Years". Armenian General Benevolent Union. Retrieved 2024-09-18.

- ^ "Why Are There No Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh?". Freedom House. Archived from the original on 2024-09-04. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

The blockade was accompanied by the regular cutting of the supply of gas and electricity, as well as disrupting lines of communication, such as telephone landlines, cellular signals, and internet. Azerbaijani state actors regularly shut down the supply of gas to Nagorno-Karabakh during the first four months of the blockade...On January 9, 2023, the high-voltage cable from Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh, the main source of electricity, was damaged in the territory of the Lachin Corridor. Azerbaijani officials did not allow any repair work on it, and the supply of electricity was never restored.

- ^ "Statement Condemning the Azerbaijani Blockade of the Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh)" (PDF). International Association of Genocide Scholars. 1 February 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

- ^ "Ensuring free and safe access through the Lachin Corridor". Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe. 2023-06-22.

85. Calculations of gas flow indicate that the gas goes to the village of Pekh, and not beyond that point, suggesting that a valve has been installed. The blockage can be checked with the level of gas pressure.

- ^ "Nagorno-Karabakh reports gas cut for second time since start of blockade". OC Media. 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ "Why Are There No Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh?", Freedom House, retrieved 2024-09-05,

In addition to creating the blockade, Azerbaijan took deliberate measures to instill a sense of insecurity in Nagorno-Karabakh. The shootings near the line of contact continued, targeting people carrying out agricultural work, which was needed for self-sustenance during the blockade.

- ^ ռ/կ, Ազատություն (2022-11-14), "Armenian PM Reacts To Reported Shooting At Farmers In Karabakh", Ազատություն ռ/կ (in Armenian), archived from the original on 2023-10-03, retrieved 2024-09-04

- ^ Khulian, Artak (2023-03-24). "Azerbaijani Troops Accused Of Shooting At Karabakh Farmers". Ազատություն ռ/կ (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 2024-04-29. Retrieved 2024-09-04.

- ^ "Azerbaijani serviceman who killed a 65-year-old civilian". English Jamnews. 2021-12-05. Retrieved 2024-09-04.

- ^ "Nagorno-Karabakh authorities warn of "critical" situation as Azerbaijan bans Red Cross vehicles | Eurasianet". eurasianet.org. Retrieved 2025-08-11.

Azerbaijan has barred the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) from using the only road connecting Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia and the outside world.

- ^ "Why Are There No Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh?". Freedom House. p. 28-30. Retrieved 2025-08-11.

- ^ Badalian, Susan; Sahakian, Nane (2023-06-16). "Relief Supplies To Karabakh Blocked By Baku". «Ազատ Եվրոպա/Ազատություն» ռադիոկայան (in Armenian). Retrieved 2025-08-11.

Azerbaijan did not allow relief supplies to and medical evacuations from Nagorno-Karabakh for the second consecutive day on Friday, aggravating a humanitarian crisis in the Armenian-populated region effectively cut off from the outside world since December.

- ^ "Report: Risk Factors and Indicators of the Crime of Genocide in the Republic of Artsakh: Applying the UN Framework of Analysis for Atrocity Crimes to the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict" (PDF), Lemkin Institute, retrieved 2024-09-05,

Prominent figures in the field of human rights, such as Juan Ernesto Mendez, the Former Special Advisor to the Secretary-General on the Prevention of Genocide (2004–2007) at the United Nations and a former UN Special Rapporteur on Torture (2010–2016), and a collection of the world's foremost scholars within the discipline of Genocide Studies, have described the blockade as indicative of genocide.

- ^ Forgey, Elisa von Joeden (2023-12-30). "Why Prevention Fails: Chronicling the Genocide in Artsakh". International Journal of Armenian Genocide Studies. 8 (2): 86–107. doi:10.51442/ijags.0046. ISSN 1829-4405.

Many Armenian officials, international genocide scholars, and international genocide prevention organizations were united in identifying Azerbaijan's actions as a mass atrocity crime, either "ethnic cleansing" or "genocide". Armenian officials tended to prefer the term "ethnic cleansing" while genocide scholars were convinced that Azerbaijan was committing genocide. The latter includes former ICC chief prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo, Genocide Watch, and the Lemkin Institute for Genocide Prevention. These same organizations, as well as the International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS), repeatedly warned about the threat of genocide in the months before Azerbaijan's September 19 attack, and, after 12 December 2022, about the already genocidal nature of Azerbaijan's blockade of Artsakh.

- ^ Vardanyan, Arnold. "In the Wake of Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict: Current Challenges to Regional Peace and International Law". Cambridge International Law Journal. Retrieved 2024-09-05.

Although Azerbaijani authorities rejected claims of ethnic cleansing, numerous international bodies, including the European Parliament, adopted a resolution declaring that the 'forced exodus' of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh 'amounted to ethnic cleansing.'

- ^ a b "Repertoire of the Practice of the Security Council: Supplement 1989–1992", United Nations, p. 469, 1992-01-01, doi:10.18356/832be109-en, ISBN 978-92-1-058175-2, retrieved 2024-08-28

- ^ a b "TURKISH BLOCKADE OF ARMENIA – Early Day Motions – UK Parliament", edm.parliament.uk, retrieved 2024-08-28,

That this House notes that 24th April 1995 marks the 80th anniversary of the genocide of 1.5 million Armenians at the hands of Ottoman Turkey; condemns this crime; calls upon the Turkish Government to acknowledge that this massacre took place; condemns Turkey's blockade of humanitarian aid to the Republic of Armenia; and calls on European union leaders to apply political and economic pressure on the Turkish authorities to bring about lifting this blockade.

- ^ a b "Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia : country studies", The Library of Congress, retrieved 2024-08-28,

In the early 1990s, the development of Azerbaijan's foreign trade was skewed by the refusal of eighteen nations, including the United States, Canada, Israel, India, and the Republic of Korea (South Korea), to import products from Azerbaijan as long as the blockade of Armenia continued. At the same time, many of those countries sold significant amounts of goods in Azerbaijan.

- ^ Saparov, Arsène (2024-09-03). "Normalizing conflict – concealing genocide? Expert neutrality in the Armenian Azerbaijani conflict". Southeast European and Black Sea Studies: 1–21. doi:10.1080/14683857.2024.2384138. ISSN 1468-3857.

During the 1990-94 conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Turkey's military involvement was limited and unofficial. For example, politically, Turkey supported Azerbaijan, by completely closing its border with Armenia in the wake of Armenian victories in 1992. This border remains closed despite the Azerbaijani victory in 2020, which removed the reason for the closure of the border. Thus, the Turkish involvement on the Azerbaijani side is currently at an unprecedented level, both politically and militarily.

- ^ a b Abrahamyan, Gayane, "Armenia: Yerevan Wants to Open Up to Iran", Eurasianet, Columbia University, archived from the original on 2022-10-30, retrieved 2024-09-04

- ^ a b Avedian, Vahagn (2013-01-01). "Recognition, Responsibility and Reconciliation: The Trinity of the Armenian Genocide". Europa Ethnica. 70 (3/4). Facultas: 77–86. doi:10.24989/0014-2492-2013-34-77. Archived from the original on 2023-12-02. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

- ^ a b c Giragosian, Richard (2016-04-08). "Armenia's National Security: External Threats, Domestic Challenges". Reassessing Security in the South Caucasus. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315603872-5 (inactive 7 August 2025). Retrieved 2024-08-21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2025 (link) - ^ Donald E. Miller, Lorna Touryan Miller (2003). Armenia Portraits of Survival and Hope. University of California Press. pp. 8–10, 34. ISBN 978-0-520-23492-5.

- ^ Sidhu, Arman (2024-08-20), "Armenia-Iran Secret Arms Deal: Implications For The South Caucasus – Analysis", Eurasia Review, retrieved 2024-08-21

- ^ Ter-Matevosyan, Vahram (2017-05-04). "Armenia in the Eurasian Economic Union: reasons for joining and its consequences". Eurasian Geography and Economics. 58 (3). Routledge: 340–360. doi:10.1080/15387216.2017.1360193. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

Suffice to say that because of the sealed borders, Armenia is one of the unique cases in the world that has 80% of its land borders closed. Borders with Georgia and Iran are the only ones open, which, in turn, makes Armenia overly dependent on them.

- ^ Ter-Matevosyan, Vahram; Mkrtchyan, Narek (2021). "The Conduct of Armenian Foreign Policy: Limits of the Precarious Balance". Small States and the New Security Environment. The World of Small States. Vol. 7. Springer International Publishing. pp. 203–215. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-51529-4_14. ISBN 978-3-030-51528-7. ISSN 2627-6003. Archived from the original on 2022-01-14. Retrieved 2024-08-21.

Armenia is one of the rare states in the world that has more than 80% of its borders sealed. Armenia has only two open borders—Georgia (219 km) in the north and Iran (44 km) in the south.

- ^ Tocci, Nathalie (2007). The Case for Opening the Turkish-Armenian Border (PDF) (Report). Trans-European Policy Studies Association.

This all the more so given that Armenia is a landlocked country, and its only practical access to the sea is through Georgia and Iran. Landlocked, with two of its borders closed, connected to its distant markets via uncertain and expensive routes through Georgia and Iran, Armenia's development is thus heavily handicapped by the current closure.

- ^ "Trump clinches Armenia-Azerbaijan deal — along with some personal branding and more Nobel Peace Prize talk". KTVZ. August 8, 2025. Retrieved August 9, 2025.

- ^ Curtis, Glenn (1995). Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia: Country Studies. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division. p. xviii. Retrieved 2024-08-22.

- ^ "Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict", CRS Reports, archived from the original on 2024-02-06, retrieved 2024-08-22,

The Azerbaijan Popular Front (PF) began a rail blockade of Armenia and Karabakh, restricting food and fuel deliveries. Anti-Armenian violence occurred in Baku and Sumgait in January 1990.

- ^ a b Rutland, Peter (1994-01-01), "Democracy and nationalism in Armenia", Europe-Asia Studies, 46 (5), Taylor & Francis Group: 839–861, doi:10.1080/09668139408412202, archived from the original on 2023-05-14, retrieved 2024-08-22

- ^ Binder, David (1992-12-20). "U.S. Warns of 'Catastrophe' Facing Armenia". The New York Times. Retrieved 2024-09-11.

- ^ a b c Curtis, Glenn (1995), Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia : country studies, D.C.: Federal Research Division, retrieved 2024-08-22,

In large part because of the earthquake of 1988, the Azerbaijani blockade that began in 1989, and the collapse of the internal trading system of the Soviet Union, the Armenian economy of the early 1990s remained far below its 1980 production levels.

- ^ Library of Congress. Federal Research Division. Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia: Country Studies. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress, 1995. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-8444-0848-4.

- ^ "Lachin is a ghost-town – a crowd of burned-out,..." UPI. Archived from the original on 17 December 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-17.

- ^ "CASE OF CHIRAGOV AND OTHERS v. ARMENIA". HUDOC – European Court of Human Rights. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

The capture of these two towns [Lachin and Shusha/Shushi] had been deemed necessary by the "NKR" forces in order to stop Azerbaijani war crimes and open up a humanitarian corridor to Armenia.

- ^ Green, Anna (2017-03-20). "Spotlight Karabakh". EVN Report. Archived from the original on 9 June 2023. Retrieved 2023-06-09.

On May 18, [1992] the Karabakh Army entered Lachin (Kashatagh), thus ending the three-year blockade.

- ^ "Dates and facts around Nagorno-Karabakh's 30-year long conflict". Euronews. 2016-04-05. Archived from the original on 20 August 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-26.

- ^ Avedian, Vahagn (2013). "Recognition, responsibility and reconciliation: the trinity of the Armenian genocide" (PDF). Europa Ethnica. 70 (70.3/4): 77–86. doi:10.24989/0014-2492-2013-34-77.

- ^ Mirzoyan, Alla (2024-08-22), Armenia, the Regional Powers, and the West, Palgrave Macmillan US, p. 73, doi:10.1057/9780230106352, ISBN 978-0-230-10635-2, archived from the original on 2022-08-04, retrieved 2024-08-22

- ^ Croissant, Michael P. (23 July 1998), The Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, p. 87, ISBN 978-0-313-07172-0, archived from the original on 2015-12-01, retrieved 2024-08-22

- ^ a b c "Turkey's "Iron Curtain": Attempts to Unlock the Armenia Border", CIVILNET, 2023-07-25, archived from the original on 2023-11-29, retrieved 2024-09-03

- ^ Brent Hierman (2017). Russia and Eurasia 2017–2018. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-4758-3517-5.

- ^ Bohlen, Celestine (1993-02-07), "Blockade and Winter Deepen Misery in Armenia", The New York Times, archived from the original on 2020-11-15, retrieved 2024-09-11,

Two weeks ago, the hospital's telephones went dead when Armenia's last functioning gas pipeline was damaged in an explosion attributed to Azerbaijani terrorists.

- ^ a b Uhlig, Mark A. (1993). "The Karabakh War". World Policy Journal. 10 (4): 47–52. ISSN 0740-2775. JSTOR 40209334.

- ^ Curtis, Glenn E. (Glenn Eldon) (1995). "Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia : country studies". (No Title). Area handbook series.

- ^ a b c Stanton, Elizabeth A.; Ackerman, Frank; Resende, Flávia (2009). The Socio-Economic Impact of Climate Change in Armenia (PDF) (Report). Somerville, MA: Stockholm Environment Institute – U.S. Center, Tufts University. Retrieved 23 August 2024.

- ^ "Armenia TED Case Study", gurukul.ucc.american.edu, archived from the original on 2017-02-27, retrieved 2024-09-03

- ^ Nadein-Raevski, V. (1992-01-01), "The Azerbaijani Armenian Conflict: Possible Paths towards Resolution", Ethnicity and Conflict in a Post-Communist World, Palgrave Macmillan UK, p. 124, doi:10.1007/978-1-349-22213-1_7, ISBN 978-1-349-22215-5, archived from the original on 2018-06-15, retrieved 2024-08-23

- ^ a b Vardanian, Astghik; Berndt, Jerry (July 1996). "Armenia's Choice". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 52 (4): 50–54. Bibcode:1996BuAtS..52d..50V. doi:10.1080/00963402.1996.11456644. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^ "Armenia's Aging Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant Alarms Caucasian Neighbors". OilPrice.com. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (1995-06-06), "Energy-starved Armenians risk a new Chernobyl", The Independent, retrieved 2024-09-05

- ^ Ter-Gabrielian, Gevork; Nedolian, Ara (April 1997). "Armenia: Crossroads or fault line of civilizations?". The International Spectator. 32 (2): 93–116. doi:10.1080/03932729708456778. ISSN 0393-2729.

- ^ Cornell, Svante E. (January 1998). "Turkey and the conflict in Nagorno Karabakh: a delicate balance". Middle Eastern Studies. 34 (1): 51–72. doi:10.1080/00263209808701209. ISSN 0026-3206.

- ^ Mirzoyan, Alla (2010). Armenia, the Regional Powers, and the West. doi:10.1057/9780230106352. ISBN 978-1-349-38124-1.

- ^ a b Migdalovitz, Carol (2003-08-08). "Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict". UNT Digital Library. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

In 1995, Armenia said that it would exclude the genocide from the bilateral agenda, if Turkey excluded Karabakh.

- ^ Galstyan, Narek (March 2013). "The main dimensions of Armenia's foreign and security policy" (PDF). Norwegian Peacebuilding Resource Center. p. 3.

It [the Georgian-Russian War of 2008] was a shock for the Armenian economy, because the country's foreign trade mainly passes through Georgia because of the Azerbaijani-Turkish blockade.

- ^ "Armenia and Turkey: From normalization to reconciliation", Brookings, 2015-02-24, archived from the original on 2024-07-09, retrieved 2024-08-23,

The August 2008 Russian-Georgian war, for example, ruptured Armenia's sole trading route through Georgia to Russia. It starkly underscored the strategic risks posed by Armenia's position, framed by closed borders with both Turkey and Azerbaijan since the 1990s.

- ^ Avedian, Vahagn (2013-10-31), "The Unsustainable European Policy towards the South Caucasus", Foreign Policy Journal, retrieved 2024-08-23

- ^ Migdalovitz, Carol (2003-08-08). "Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict". UNT Digital Library. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

Turkey set Armenia's abandonment of territorial designs on Turkey (i.e., on Kars and Ardahan provinces that Lenin ceded to Turkey in 1921), the "politicization" or internationalization of allegations of Turkey's culpability for the "genocide" of Armenians, and a Karabakh solution as preconditions to diplomatic ties. It later added a demand for a corridor between Azerbaijan and Nakhichevan.

- ^ "Armenia gives assurances on border recognition". 2009-04-18. Archived from the original on 18 April 2009. Retrieved 2024-09-03.

- ^ Reichardt, Adam (2023-04-29), "Nagorno-Karabakh: no clear path out of the crisis – New Eastern Europe", New Eastern Europe, retrieved 2024-09-05,

The local Armenians fear that this is a prelude to an Azerbaijani attempt to fully drive them all out of their homeland.

- ^ Edmond Y. Azadian (1999). History on the Move Views, Interviews and Essays on Armenian Issues. Wayne State University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-8143-2916-0.

Today Turkey and Azerbaijan continue to implement their joint blockade against Armenia...Their intentions are very transparent: to destroy Armenia's economic and political infrastructure, to force the population into starvation, and to squeeze that population out of existence.

- ^ "International Association of Genocide Scholars Executive and Advisory Boards: Statement Condemning the Azerbaijani Blockade of the Artsakh (Nagorno-Karabakh)" (PDF). The International Association of Genocide Scholars. 1 February 2023. Retrieved 5 September 2024.

The government of Azerbaijan, encouraged by its ally Turkey, has long promoted official hatred of Armenians, has fostered impunity for atrocities committed against Armenians, and has issued repeated threats to empty the region of its indigenous Armenian population.

- ^ Hill, Nathaniel (2023-02-24), "Genocide Emergency: Azerbaijan's Blockade of Artsakh", genocidewatch, retrieved 2024-09-05,

The blockade has created a dire humanitarian crisis among the 120,000 people living in Artsakh and is a clear attempt by the Azerbaijani government to starve, freeze, and ultimately expel Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh.

- ^ Kévorkian, Raymond (2011), The Armenian genocide : a complete history, London: I.B. Tauris, pp. 702–706, ISBN 9781848855618, retrieved 2024-08-23

- ^ a b c d Miller, Donald E.; Miller, Lorna Touryan; Berndt, Jerry (September 2003). Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780520234925.

- ^ a b Miller, Donald E.; Miller, Lorna Touryan; Berndt, Jerry (September 2003). Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope (1st ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 116. ISBN 9780520234925.

- ^ Times, Los (1993-01-24), "Explosion of pipeline plunges Armenia into cold and dark", baltimoresun.com, archived from the original on 2023-09-01, retrieved 2024-08-26

- ^ a b c d Curtis, Glenn (1995), Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia : country studies, D.C.: Federal Research Division, retrieved 2024-08-22

- ^ Front Lines. U.S. Agency for International Development. 1992. p. 5.

- ^ a b c Caroline Cox, John Eibner (1993). Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh. Institute for Religious Minorities in the Islamic World, 1993. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-3-9520345-2-1.

- ^ a b c Bohlen, Celestine (1993-02-07), "Blockade and Winter Deepen Misery in Armenia", The New York Times, retrieved 2024-09-11

- ^ "Armenia's Isolation Grows Only Deeper", The New York Times, 2004-12-26, retrieved 2024-09-11,

The limited opportunities have contributed to an exodus of working-age Armenians since independence 13 years ago, with some estimates putting the population loss at nearly 30 percent.

- ^ a b "Armenia – Caucasus, Soviet Union, Genocide", Encyclopedia Britannica, archived from the original on 2024-08-10, retrieved 2024-08-21,

A blockade imposed by Azerbaijan in 1989 had devastated the Armenian economy; the resulting severe decline in living conditions led hundreds of thousands of Armenians to emigrate.

- ^ Bohlen, Celestine (1993-02-07), "Blockade and Winter Deepen Misery in Armenia", The New York Times, archived from the original on 2020-11-15, retrieved 2024-09-11

- ^ a b c Curtis, Glenn (1995). Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia: Country Studies. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division. Retrieved 2024-08-22.

- ^ Tocci, Nathalie (2007). "The Case for Opening the Turkish-Armenian Border" (PDF). Trans-European Policy Studies Association.

The closure significantly raises de facto distances and thus transport costs. For example, the route from Yerevan to the Turkish border town of Igdir is lengthened by a factor of 10 by the closed border, as traffic must transit through Georgia.

- ^ Mirzoyan, Alla (2024-08-22), Armenia, the Regional Powers, and the West, Palgrave Macmillan US, p. 106, doi:10.1057/9780230106352, ISBN 978-0-230-10635-2, archived from the original on 2022-08-04, retrieved 2024-08-22

- ^ "In Vartan Oskanian's Words, Turkey Casts Doubt On The Treaty Of Kars With Its Actions". Armenians Today. Istanbul: All Armenian Mass Media Association. Noyan Tapan. 13 December 2006. Archived from the original on 9 October 2007. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- ^ "Treaty of Kars". groong.org. Retrieved 2025-08-14.

- ^ a b Davidian, David (2018-09-11), "The Curious Treaty of Kars – Modern Diplomacy", Modern Diplomacy, archived from the original on 2024-02-29, retrieved 2024-08-26

- ^ Mirzoyan, Alla (2010-01-01), "Turkey: "The Other"", Armenia, the Regional Powers, and the West, Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 55–106, doi:10.1057/9780230106352_3, ISBN 978-1-349-38124-1, archived from the original on 2018-06-12, retrieved 2024-08-26,

According to experts, such a breakthrough was unprecedented in world history: not a single country immediately during the first year of its independence had so actively aspired to development of friendly relations and cooperation with the state that had eliminated a good half of the nation, living on its own historical territory, had plunged it in demographic catastrophe and deprived it of the largest portion of its territory.

- ^ "Vahagn Avedian, Knowledge and Acknowledgement in the Politics of Memory of the Armenian Genocide. Londres et New York, Routledge, 2019, 304 p.", Études arméniennes contemporaines, no. 12, Bibliothèque Nubar de l'UGAB, p. 216, 2019-02-28, doi:10.4000/eac.2318, ISSN 2269-5281, retrieved 2024-08-26

- ^ Mirzoyan, Alla (2010-01-01), "Turkey: "The Other"", Armenia, the Regional Powers, and the West, Palgrave Macmillan US, p. 105, doi:10.1057/9780230106352_3, ISBN 978-1-349-38124-1, archived from the original on 2018-06-12, retrieved 2024-08-26,

As Eduard Agajanov suggested that the need to downplay the necessity for the border opening is dictated by the fundamental goal 'to preserve the current oligarchic economic system in Armenia, which cannot survive if the borders are opened and competition with Turkish goods becomes tougher.'

- ^ "Report: No Big Gains to Armenia if Turkey Lifts Blockade", Eurasianet, retrieved 2024-08-26

- ^ a b "Vahagn Avedian, Knowledge and Acknowledgement in the Politics of Memory of the Armenian Genocide. Londres et New York, Routledge, 2019, 304 p.", Études arméniennes contemporaines, no. 12, Bibliothèque Nubar de l'UGAB, p. 216, 2019-02-28, doi:10.4000/eac.2318, ISSN 2269-5281, retrieved 2024-08-26,

The perceived animosity from Turkey and Azerbaijan has also been abused by the political leadership inside Armenia and has become a real impediment to the development of democracy in the country. This is perhaps most tangible in the fact that the opposition in Armenia is restrained in its efforts to challenge the ruling elite. Fearing that any confrontation could potentially lead to public protests or, even worse, clashes and political upheaval, the general notion is justified in being wary that a similar turbulence would be exploited by Azerbaijan in the ongoing Karabakh conflict.

- ^ "Ten years since start of Karabakh movement – Armenia", ReliefWeb, 1998-02-20, archived from the original on 2022-03-19, retrieved 2024-08-26

- ^ Tocci, Nathalie, "The Closed Armenia-Turkey Border: Economic and Social Effects, Including Those on the People; and Implications for the Overall Situation in the Region" (PDF), www.europarl.europa.eu, archived from the original on 26 June 2024, retrieved 2024-08-26,

The closure of the Turkish-Armenian border in April, 1993 has generated grave costs to Armenia. A re-opening of the border would benefit greatly Armenia's economy and society, even if some economic sectors may suffer from external competition. The opening would also favourably impact Armenia's political development and open the way to the county's full integration into the region.

- ^ Sheehan, Ivan (2021-09-03), "A Plea for Compromise – Reconnecting Armenia With the World", RealClearEnergy, retrieved 2024-08-27

- ^ a b c d Avedian, Vahagn (2013-10-31), "The Unsustainable European Policy towards the South Caucasus", Foreign Policy Journal, retrieved 2024-08-21

- ^ Croissant, Michael P. The Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict: causes and implications. London: Praeger, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 1998. ISBN 978-0-275-96241-8.

- ^ Rutland, Peter (1994-01-01), "Democracy and nationalism in Armenia", Europe-Asia Studies, 46 (5), Taylor & Francis Group: 839–861, doi:10.1080/09668139408412202, retrieved 2024-08-27

- ^ Ohanyan, Anna; Broers, Laurence (2020). Armenia's Velvet Revolution Authoritarian Decline and Civil Resistance in a Multipolar World. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-78831-717-7.

Armenia's GDP dropped by 56 per cent in 1990-3, and half a million jobs - accounting for one third of all those employed - disappeared.

- ^ Mirzoyan, Alla (2010-01-01), "Turkey: "The Other"", Armenia, the Regional Powers, and the West, Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 105–106, doi:10.1057/9780230106352_3, ISBN 978-1-349-38124-1, archived from the original on 2018-06-12, retrieved 2024-08-26

- ^ EurasiaNet Eurasia Insight - Azerbaijan: Turkey Could Prove Spoiler for Nagorno-Karabakh Peace, archived from the original on 2004-06-18, retrieved 2024-08-27

- ^ Curtis, Glenn (1995), Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia : country studies, D.C.: Federal Research Division, retrieved 2024-08-22,

'To survive the cold, Armenians in Yerevan cut down the city's trees, and plans were made to start up the nuclear power plant at Metsamor.'... 'Environmental conditions in Armenia have been worsened by the Azerbaijani blockade of supplies and electricity from outside. Under blockade conditions, the winters of 1991–92, 1992–93, and 1993–94 brought enormous hardship to a population lacking heat and electric power. (The large-scale felling of trees for fuel during the winters of the blockade has created another environmental crisis.) The results of the blockade and the failure of diplomatic efforts led the government to propose reconstruction of the Armenian Atomic Power Station at Metsamor, which was closed after the 1988 earthquake because of its location in an earthquake-prone area and which had the same safety problems as reactors listed as dangerous in Bulgaria, Russia, and Slovakia. After heated debates over start-up continued through 1993, French and Russian nuclear consultants declared operating conditions basically safe. Continuation of the blockade into 1994 gave added urgency to the decision (see Energy, this ch.).'