Tseklapai

| Tseklapai | |

|---|---|

| Waishon | |

Tseklapai  Tseklapai Tseklapai (India) | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 4,122 ft (1,256 m)[1] |

| Coordinates | 24°24′13″N 93°40′11″E / 24.4035°N 93.6698°E |

| Geography | |

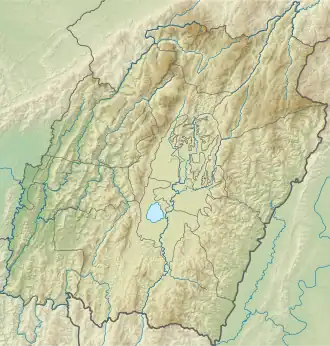

| Location | Churachandpur district, Manipur |

| Country | India |

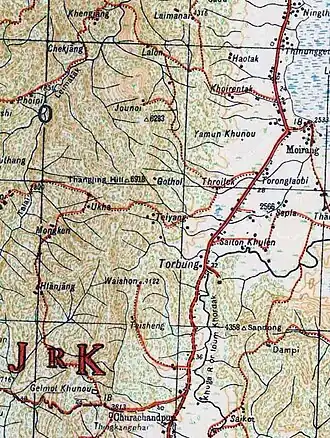

Tseklapai (also called Tseklapi and Cheklapai),[2] is described as a mountain in southern Manipur, India.[3] It was evidently near Torbung and Moirang.[4] It was used for an army camp,[5] in fact, as the headquarters of the southern frontier defence of Manipur.[6] During the Lushai Expedition of 1871–1872, Manipur was asked to station troops here for keeping a watch on the Kamhau-Suktes.[7]

Descriptions indicate Tseklapai to be a subsidiary range of the Thangjing Hills range.

Geography

The Thangjing Hills range with a peak at 2,100 metres (6,900 ft) above the mean sea level, is regarded as the western hill range that bounds the Imphal Valley. The majority of the range is in Churachandpur district, a hill district dominated by the Kuki-Zo people.

Near Torbung and to its south, there is a subsidiary range to the east of Thangjing Hills range, with a peak called Waishon at 1,256 metres (4,122 ft).[1] The Lanva River that drains into the Khuga River near Churachandpur originates here, flowing in the gap between the two ranges. The Loklai river that flows into Torbung also originates in this range. The recorded mentions of Tseklapai indicate this range. Cheitharol Kumbaba mentions Thangal Major catching three elephants here in 1862 and taking them to Imphal.[4]

History

Saiton Hills expedition

In 1789, King Bhagyachandra (Chingthang-Khomba) launched an expedition to Saiton Hills bordering the Imphal Valley, lying to the east of the Khuga River valley. The Manipur forces set up a camp at Cheklapai, where Bhagyachandra also took his base. Then, they attacked Saiton Hills and "scattered" the hill villages. Bhagyachandra too went in and sang Oukri (victory song). Later, when the troops went out to search for food and loot, the tribesmen attacked, killing nine people. The troops fled and the tribesmen took possession of the big metal gun and arms and ammunition. The end result seems to have been ambiguous.[2][5] Cheitharol Kumbaba states that the soldiers blocked up the Loklai river.[5]

Ths Saiton Kukis (said to be Haokips) submitted later in 1858, to King Chandrakirti, in order to obtain protection from Kamhau-Suktes.[2]

British Raj and Kamhau-Suktes

In 1824, Manipur came under the protection of the British Empire in India, who established a political agency in Manipur in 1835. Around the same time, the Lushais in present-day Mizoram and Kamhau-Suktes in present-day Chin State (of Myanmar) acquired European guns, and started putting pressure on the hills to the south of Manipur valley. The tribes inhabiting them (mainly Thadou Kukis, called "Khongjais" in Manipur) moved out into the other hill regions of Manipur.[8] The British political agent, William McCulloch, took care of their resettlement in Manipur's hill regions.[9] He also provided arms to a suitable number of Kukis and settled them in the frontier regions in what came to be known as "sepoy villages". They were given the task of sending scouts to watch the hostile southern tribes so as to avoid raids on Manipur territory.[10] In 1871–72, Tseklapai was said to be the headquarters of the southern frontier posts of Manipur.[11] Some of the reports indicate that these posts were manned by Kuki troops.[12]

Notes

References

- ^ a b Survey of India mapsheet 83-H, 1944.

- ^ a b c Kuki Research Forum on objective historical position of the Kukis in Manipur, Ukhrul Times, 25 May 2022.

- ^ Brown, Statistical Account of Manipur (1874), p. 5.

- ^ a b Parratt, The Court Chronicle, Vol. 3 (2013), p. 97: "[Sakabda 1784 (1862 CE)] Friday, Thangkan Major and others, after catching three elephants from Torpung Cheklapai in Moirang, returned with them."

- ^ a b c Parratt, The Court Chronicle, Vol. 2 (2009), p. 34.

- ^ Pau, Indo-Burma Frontier (2019), p. 67.

- ^ Pau, Border and Belonging (2022a), p. 280: [Quoting General Bourchier] "It was never my intention that the officer commanding should be tied down to Moirung, but that it should be moved to the south of the Munnipoor valley, but not further than the point marked Tseklapi in your map (spelt Yolepee by Colonel McCulloch), and which is about the southern frontier of Munnipoor".

- ^ Brown, Statistical Account (1874), p.16: "... in that part of the hill country lying north of that occupied by the Lushai tribe of Kukis, there are no inhabitants whatever for about six days' journey.".

- ^ Mackenzie, Relations with the Hill Tribes (1884), pp. 156–157: [Quoting McCulloch] "In the hills all round the valley, and to the west, beyond the Barak and Mookroo, are Kookies [Kukis]" over whom I exercise a general superintendence to prevent oppression of the people, driven from their homes by their enemies in the south.".

- ^ Mackenzie, Relations with the Hill Tribes (1884), p. 157.

- ^ Pau, Indo-Burma Frontier (2019), p. 67, Table 3.1.

- ^ Annual Administration Report for 1875–76 (1876), p. 5: "On the 22nd Bysak (3rd May 1876) the headmen of the Khongjai sepoys stationed on the Moirang frontier, named Poomlul and Munglep of Lowsow, brought a Kamhow [Kamhau] head, and their statement as given is written below: [We], with seventy Khongjai sepoys proceeded to reconnoitre towards Tseklapi; on our arrival there, [..] we spied [on] an advance party of Kamhow force and proceeded as far as the banks of the Khooka river [Khuga river] ....

Bibliography

- Annual Administration Report of the Munnipoor Agency, For the year ending 30th June 1875–76, Selections from the Records of the Government of India, Foreign Department, Calcutta: Foreign Department Press, 1876 – via archive.org

- Brown, R. (1874), Statistical Account of the Native State of Manipur and the Hill Territory under Its Rule, Calcutta: Office of the Superintendent of Government Printing

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1884), History of the Relations of the Government with the Hill Tribes of the North-East Frontier of Bengal, Calcutta: Home Department Press – via archive.org

- McCulloch, W. (1859). Account of the Valley of Munnipore and of the Hill Tribes. Selections from the Records of the Government of India (Foreign Department). Calcutta: Bengal Printing Company. OCLC 249105916 – via archive.org.

- Parratt, Saroj Nalini Arambam (2005). The Court Chronicle of the Kings of Manipur: The Cheitharon Kumpapa, Volume 1. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415344302.

- Parratt, Saroj Nalini Arambam (2009). The Court Chronicle of the Kings of Manipur: The Cheitharon Kumpapa, Volume 2. Foundation Books / Cambridge University Press India. ISBN 978-81-7596-854-7.

- Parratt, Saroj Nalini Arambam (2013). The Court Chronicle of the Kings of Manipur: The Cheitharon Kumpapa, Volume 3. Foundation Books / Cambridge University Press India. ISBN 978-93-8226-498-9 – via Cambridge Core.

- Pau, Pum Khan (2019), Indo-Burma Frontier and the Making of the Chin Hills: Empire and Resistance, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781000507454

- Pau, Pum Khan (2022a), "Border and Belonging: Historicizing the Question of Indigeneity and Citizenship in Manipur", in Gorky Chakraborty (ed.), Citizenship in Contemporary Times: The Indian Context, Taylor & Francis, doi:10.4324/9781003345152-20, ISBN 9781000807721

- Pau, Pum Khan (2022b), "Border and Belonging: Historicizing the Question Of Indigeneity and Citizenship in Manipur", in Gorky Chakraborty (ed.), Citizenship in Contemporary Times: The Indian Context (E-book ed.), Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9781032347127

External links

- Terrain map of Waishon peak and its vicinity, OpenStreetMap, retrieved 28 March 2025.

- Lanva River, OpenStreetMap, retrieved 28 March 2025.