Treaty of Fribourg (1516)

The Treaty of Fribourg, more commonly known as the "Perpetual Peace," is a treaty of peace signed in Freiburg on 29 between France under Francis I and the Swiss Confederation of the Thirteen Cantons.

It was inscribed in the UNESCO International Memory of the World Register in 2025.[1].

Negotiations

Negotiations between the French and the Swiss began as early as August, even before the Battle of Marignano (13–14)[2]. A preliminary treaty was signed by Swiss captains and French plenipotentiaries on 8 in Gallarate. The Treaty of Gallarate[3] met most of the demands of the King of France, who sought an alliance with the Confederation and to secure exclusive recruitment of Swiss mercenaries. In return, the King of France pledged to pay one million gold écus and an annual pension of 2,000 francs per canton.

Although these proposals appeared generous, they were not unanimously accepted by the Swiss. They were well-received in Bern, Fribourg, and Solothurn, but ultimately rejected by the other cantons, which chose to adhere to treaties binding them to the Duke of Milan, Maximilian Sforza, the Pope, and the anti-French coalition formed by Julius II in 1510. Soldiers from Bern, Fribourg, and Solothurn returned to Switzerland, while the other cantons marched against the French, attacking them unsuccessfully at Marignano a few days later. After the battle, negotiations resumed between the French and the Swiss, but the latter were deeply divided. A new treaty, signed in Geneva on 7[4], was ratified by seven cantons (Bern, Fribourg, Solothurn, Glarus, Zug, Lucerne, Appenzell) and the half-canton of Obwalden, while the cantons of Uri, Schwyz, Zürich, Schaffhausen, Basel, and the half-canton of Nidwalden remained staunchly hostile to France. The Confederation was in a state of near-secession for several months, and efforts by the cantons to reach a consensus were fruitless[5].

The five refractory cantons authorized Emperor Maximilian I to recruit soldiers from their territories for a new expedition in Italy. Thus, 15,000 Swiss from the refractory cantons faced 6,000 Swiss, mostly Bernese, hired by the King of France before Milan, though they did not fight each other. The Emperor, lacking funds, saw his army disband due to unpaid wages[6]. The King of France, realizing he could not immediately demand an alliance with the Swiss if he wished to convince the most reluctant cantons, also agreed to make concessions regarding the districts of the Duchy of Milan annexed by the Swiss in 1512, which he had wanted to repurchase for 300,000 écus to restore the territorial integrity of Milan.[6]

Although often considered the beginning of Swiss neutrality[7], the Treaty of Fribourg did not prohibit Swiss intervention abroad. It was in the 17th century that Switzerland evolved toward neutrality. Marked by the religious conflicts ravaging Europe, the Swiss remained aloof from military operations to preserve coexistence between Protestants and Catholics.[7]

.jpg)

Details

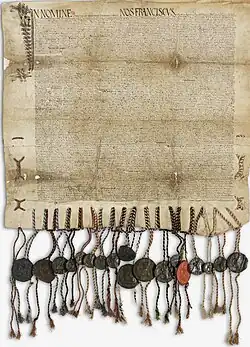

This treaty is a royal charter, drafted as a letter patent, authored by both the King of France and the Swiss cantons and their allies. It is validated by the affixing of the seals of the King of France (although the French copy, unlike the Swiss copy, was never sealed by the French chancery), the thirteen cantons, arranged in a strict protocol order (Zürich, Bern, Lucerne, Uri, Schwyz, Unterwalden, Zug, Glarus, Basel, Fribourg, Solothurn, Schaffhausen, Appenzell), and their allies (Valais, Grisons, abbot and city of St. Gallen, city of Mulhouse)[8]. The Chancellor of Fribourg was tasked with collecting the seals of the cantons after the treaty was signed. He traveled from canton to canton, taking the quickest and most direct route, not necessarily respecting the hierarchical order in his "tour of seals." The aim was to act as swiftly as possible, as the ambassadors Peter Falck and Hans Schwarzmurer were waiting for his return to set out for Paris with both copies of the treaty: one for France and one for the Confederates, which they were to bring back, duly sealed with the great seal of the King of France[9].

After a preamble deploring the consequences of fratricidal war among Christians, the treaty sets out in thirteen articles the diplomatic and economic conditions of the peace[10]

General provisions

- No enmity between the King of France and the cantons arising from past wars shall persist (art. 1).

- Prisoners from both sides shall be released without any compensation (art. 2).

- Both parties shall strive to avoid further hostilities: in case of conflict, amicable justice shall be preferred (art. 7).

- Neither party shall assist the other's enemies, for example, by allowing them passage through their territory (art. 8).

- Each party, after listing its allies in Europe, affirms that if one of its allies wishes to wage war against the other party, it shall not support its ally. For instance, if the German Emperor, an ally of the Swiss, wished to wage war against the Kingdom of France, the Swiss would not assist him or allow passage through their lands. In other words, a diplomatic preference is given to the other party, reflecting a form of neutrality on both sides (art. 13).

Individuals and specific cases

- Swiss foot soldiers and mercenaries with grievances against the King of France (many had been recruited by Louis XII despite prohibitions by cantonal authorities) must resolve their disputes independently, according to provisions outlined after the thirteen articles (art. 3).

- Individuals allied with Louis XII or the Confederation (notably those who obtained combourgeoisie) may benefit from the treaty’s provisions, except those “outside the Confederation’s limits and of a nation and language other than German” (art. 4).

Financial provisions

- The King offers the Swiss cantons 700,000 gold écus, including 400,000 for commitments made by Louis de La Trémoille in the Treaty of Dijon[11] and 300,000 for their expenses in the Italian campaigns (art. 6).

- An annual pension of 2,000 francs is granted to the thirteen cantons and the Valais; another 2,000 francs in annual rent is distributed among the cantons’ other allies: the abbot and city of St. Gallen, County of Toggenburg, city of Mulhouse, Free State of the Three Leagues, and County of Gruyère (art. 10).

Territorial arrangements

- The King recognizes the Confederation’s control over Bellinzona and the upper Ticino valley, as well as Locarno, Valle Maggia, Lugano, Mendrisio, the present-day Canton of Ticino, and the Valtellina with Bormio and Chiavenna. Of the 1512 acquisitions, only Luino and the Domodossola valley escape the Confederation. The King offers the Swiss the option to repurchase Lugano, Locarno, and Valle Maggia for 300,000 écus, giving them one year to decide. Had they accepted, the King could have recovered much of the former Milanese possessions, except notably Bellinzona.

Economic and commercial provisions

- Swiss merchants are confirmed their franchises and liberties for trade in Lyon. The King of France, Duke of Milan, also pardons Milanese who joined the Swiss and settled in the castles of Locarno, Lugano, and Milan (art. 5).

- The principle of free passage for merchants and goods in the territories of both parties is reaffirmed, without changes to toll regulations (e.g., no increase in toll amounts) (art. 9).

- Bellinzona, Lugano, and Locarno are confirmed the privileges previously granted by the Dukes of Milan (notably on tolls, gabelles, and salt purchases) (art. 11).

See also

References

- ^ "Registre Memoire du monde de l'UNESCO" [UNESCO Memory of the World Register]. www.unesco.org (in French). Retrieved 17 April 2025.

Liste des 74 nouveaux éléments du patrimoine documentaire inscrits au Registre international Mémoire du monde en 2025

- ^ Sablon du Corail, Amable (2015). 1515. Marignan. Paris: Tallandier. pp. 208–227.

- ^ Barrillon, Jean (1897). Journal de Jean Barrillon, secrétaire du chancelier Duprat [Journal of Jean Barrillon, Secretary to Chancellor Duprat] (in French). Paris: Société de l'histoire de France. pp. 102–108.

- ^ Dumont, Jean. Corps universel diplomatique [Universal Diplomatic Corpus] (in French). Vol. IV, first part. p. 418.

- ^ von Segesser, Philipp Anton (1869). Amtliche Sammlung der ältern eidgenössischen Abschiede [Official Collection of Older Swiss Confederation Resolutions] (in German). Vol. 3, part II (1500–1520). Lucerne, Zürich. pp. 944 and following.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Guicciardini, Francesco (1996). Histoire d'Italie, 1492–1534 [History of Italy, 1492–1534]. Vol. II. Paris: Robert Laffont. pp. 75–80.

- ^ a b "La neutralité suisse n'est pas née à Marignan" [Swiss Neutrality Was Not Born at Marignano]. Tribune de Genève. 2015.

- ^ Dorthe, Lionel (2016). La paix de Fribourg, 1516: catalogue d'exposition = Der Frieden von Freiburg, 1516: Ausstellungskatalog [The Peace of Fribourg, 1516: Exhibition Catalog]. Fribourg: Archives de l'État de Fribourg. p. 20.

- ^ Dafflon, Alexandre; Dorthe, Lionel; Gantet, Claire (2018). Après Marignan, la paix perpétuelle entre la France et la Suisse 1516–2016 : Actes des colloques de Paris, 27 septembre / Fribourg, 30 novembre 2016 [After Marignano, the Perpetual Peace between France and Switzerland 1516–2016: Proceedings of the Paris, 27 September / Fribourg, 30 November 2016 Conferences]. Mémoires et documents publiés par la Société d'histoire de la Suisse romande / 4. Lausanne: Société d'histoire de la Suisse romande / Archives de l'État de Fribourg. p. 42.

- ^ Based on the original French copy of the treaty (National Archives, Trésor des chartes, J 724, No. 2).

- ^ Vissière, Laurent; Marchandisse, Alain; Dumont, Jonathan (2013). 1513 - L'année terrible. Le siège de Dijon [1513 - The Terrible Year. The Siege of Dijon] (in French). Paris: Faeton.

Bibliography

- Dafflon, Alexandre; Dorthe, Lionel; Gantet, Claire (2018). Après Marignan, la paix perpétuelle entre la France et la Suisse 1516–2016 : Actes des colloques de Paris, 27 septembre / Fribourg, 30 novembre 2016 [After Marignano, the Perpetual Peace between France and Switzerland 1516–2016: Proceedings of the Paris, 27 September / Fribourg, 30 November 2016 Conferences]. Mémoires et documents publiés par la Société d'histoire de la Suisse romande (in French). Vol. 14. Lausanne: Société d'histoire de la Suisse romande / Archives de l'État de Fribourg. ISBN 9782940066162.

- Dafflon, Alexandre; Dorthe, Lionel (2016). "Fribourg, capitale diplomatique (1516)" [Fribourg, Diplomatic Capital (1516)]. Zeitschrift für schweizerische Archäologie und Kunstgeschichte [Swiss Journal of Art and Archaeology]. 73 (1+2): 145–158.

- Dorthe, Lionel (2019–2020). "Fribourg et la paix (1474/1476–1516): quelle solennité pour quel effet?" [Fribourg and Peace (1474/1476–1516): What Solemnity for What Effect?]. Mémoires et documents de la Société pour l'Histoire du Droit et des Institutions des anciens pays bourguignons, comtois et romands [Memoirs and Documents of the Society for the History of Law and Institutions of the Former Burgundian, Comtois, and Romand Countries]. 76: 45–70.

External links

- "Text of the treaty in French".

- "Call for papers for the international conference La Paix perpétuelle de 1516 : Fribourg, capitale diplomatique (30 November 2016)". Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 10 July 2025.

- Lionel Dorthe (2016). "La paix de Fribourg, 1516: catalogue d'exposition = Der Frieden von Freiburg, 1516: Ausstellungskatalog" (PDF). Fribourg: Archives de l'État de Fribourg.