Tonypandy riots

| Miners Strike of 1910–11 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Great Unrest | |||

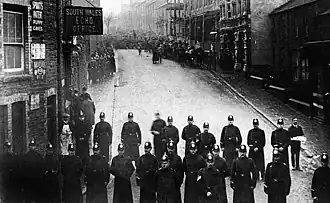

Police blockade a street during the events of 1910–1911 | |||

| Date | September 1910 – August 1911 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Lock-out in Penygraig | ||

| Goals | Higher wages, better living conditions | ||

| Methods | |||

| Resulted in | Negotiated end to the strike | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 1 miner | ||

| Injuries | 80 police and over 500 citizens | ||

| Arrested | 13 miners | ||

| Damage | Private property in Tonypandy | ||

The Miners' Strike of 1910–11 was an industrial dispute by coal miners in parts of South Wales over wages and working conditions, culminating in violent confrontations with police and the deployment of military forces.

What became known as the Tonypandy riots[1] of 1910 and 1911 (sometimes collectively known as the Rhondda riots) were a series of violent confrontations between striking coal miners and police that took place at various locations in and around the Rhondda mines of the Cambrian Combine, a consortium of mining companies in South Wales. The disturbances arose from an industrial dispute that began when the Naval Colliery Company locked out workers at the Ely Pit in Penygraig over payment rates for a new coal seam. By November 1910, approximately 12,000 miners employed by the Cambrian Combine were on strike.

The most serious violence occurred on the evening of 8 November 1910, when striking miners clashed with the Glamorgan Constabulary, reinforced by officers from Bristol and other forces.[2] Home Secretary Winston Churchill's decision to deploy military forces to the area generated significant controversy and lasting resentment in Wales.[3] One miner, Samuel Rhys, died from head injuries, and hundreds of police officers and civilians were injured during the confrontations. The strike continued until August 1911, when miners returned to work having failed to achieve their wage demands.

The events became the subject of significant historical debate, with historians disagreeing about Churchill's role and the broader political significance of the confrontations for the Welsh labour movement.

Background

Industrial conditions in South Wales

By 1910, the South Wales Coalfield had become one of the largest coal-producing regions in the world, with the Rhondda Valley alone producing 56.8 million tons of coal in 1914, representing 19.7 percent of Britain's total coal output.[4] The rapid industrial expansion of the late 19th century had transformed the economic and social landscape of the South Wales Valleys. Between 1881 and 1911, Glamorgan experienced inward migration of more than 330,000 people from elsewhere in Wales and neighbouring parts of England, drawn by employment opportunities in the expanding coalfield.[5]

Working conditions in the South Wales coal mines were notoriously dangerous and difficult. The coal seams were particularly challenging to work due to the dry, gaseous nature of Welsh coal, which made mines prone to explosion, and the presence of numerous geological faults that created layers of rock and shale.[4] Contemporary accounts described miners working "away from the sunlight and fresh air, sometimes in a temperature of up to 90°C, every movement of the day, inhaling coal and shale dust, perspiring so abnormally... the roof perhaps 18 inches low, perhaps 20 feet high, ears constantly strained for movements in the strata on which his limbs or his life is dependent."[4]

Prior to 1912, there was no minimum wage in the mining industry, and miners' pay was typically calculated by the weight of saleable coal extracted rather than by hourly rates or weekly wages.[4] This piece-rate system created ongoing disputes between miners and owners over payment rates for different seams, particularly when geological conditions made extraction more difficult or dangerous.

Formation of the Cambrian Combine

The period leading up to 1910 was marked by increasing concentration of ownership in the South Wales coal industry. The most significant example of this consolidation was the expansion of the Cambrian Combine under the directorship of D. A. Thomas (later Lord Rhondda). Thomas had inherited mining interests from his father Samuel, who had commenced sinking operations at Cambrian Collieries in Clydach Vale in 1871.[6] Following Samuel Thomas's death in 1879, D. A. Thomas expanded the business substantially, forming Cambrian Collieries Limited with a share capital of £600,000 in 1895.[6]

Between 1907 and 1910, Thomas systematically absorbed a succession of local collieries through the Cambrian Trust Limited, acquiring controlling interests in the Glamorgan Coal Company in 1907, 67% of the Naval Colliery Company in 1908, and bringing Britannic Merthyr Coal Company and Penrhiwfer Collieries under his control by 1910.[6] By 1910, the Cambrian Combine employed a total workforce of approximately 12,000 miners and produced almost 3 million tons of coal annually, making it one of the largest mining operations in Wales.[7]

Large companies like the Cambrian Combine were able to rely on the support of the Monmouthshire and South Wales Coalowners Association (M&SWCA), which provided financial backing for individual companies to impose lock-outs as a disciplinary measure against workers who resisted wage reductions or changes to working conditions.[5] This organised power of capital contrasted with the more fragmented structure of the South Wales Miners' Federation (SWMF), which was a federation of autonomous districts rather than a centralised union, a form of organisation that often obstructed united action against the coalowners' offensive.[5]

The Ely Pit dispute

The immediate cause of the 1910 conflict arose when the Naval Colliery Company, part of the Cambrian Combine, opened a new coal seam at the Ely Pit in Penygraig. After a short test period to determine future extraction rates, management claimed that the approximately 70 miners working the seam were deliberately working more slowly than possible.[8] The miners disputed this assessment, arguing that the new Bute seam was significantly more difficult to work than other seams due to a substantial stone band running through it, which made coal extraction both more dangerous and less productive.[8]

The company initially offered one shilling and ninepence per ton, plus one penny for stone removal. The miners, citing the dangerous and difficult conditions, demanded two shillings and sixpence per ton.[4] When negotiations failed to reach a satisfactory agreement, D. A. Thomas decided to force the issue through industrial action. On 1 September 1910, the owners posted a lock-out notice that closed the entire Ely Pit to all 950 workers, not merely the 70 miners working the disputed seam.[8]

The lock-out immediately escalated the dispute beyond the original wage disagreement. The Ely Pit miners responded by going on strike, and the Cambrian Combine brought in strikebreakers from outside the area.[8] The miners reacted by establishing picket lines around the work site to prevent the employment of non-union labour.

Escalation to general strike

The dispute at the Ely Pit quickly gained wider support within the South Wales mining community. On 1 November 1910, the entire membership of the South Wales coalfield was balloted for strike action by the South Wales Miners' Federation, resulting in all 12,000 men working for mines owned by the Cambrian Combine going on strike in solidarity with the Ely Pit workers.[8] By winter 1910, the number of striking miners had grown to approximately 30,000 as the dispute spread to other collieries.[4]

Attempts at conciliation were made through the establishment of a conciliation board, with the respected miners' leader William Abraham (known as "Mabon") acting on behalf of the miners and F. L. Davis representing the owners' interests.[8] Although the conciliation process initially appeared promising, with an agreed wage of 2s 3d per ton eventually negotiated, the Cambrian Combine workforce ultimately rejected this compromise agreement, preferring to continue their industrial action.[8]

The rejection of the negotiated settlement reflected broader tensions within the South Wales mining community. Many miners, particularly younger workers, had become increasingly militant and were influenced by syndicalist ideas that challenged the more conciliatory approach favoured by established leaders like Abraham.[5] This growing radicalism would later contribute to the development of documents such as The Miners' Next Step (1912), which advocated for more confrontational tactics against mine ownership.

Preparations for confrontation

As the strike continued into November 1910, both sides began preparing for potential confrontation. The coal owners, many of whom were also local magistrates, hoped that importing blackleg labour would break the strike and force the miners back to work on management terms.[4] They secured the support of Captain Lionel Lindsay, the Chief Constable of Glamorgan, who agreed to put his force on standby and coordinate with law enforcement from Bristol and other cities in South Wales if additional police resources were required.[4]

On 2 November 1910, the authorities in South Wales began enquiring about the procedures for requesting military aid in the event of disturbances caused by the striking miners.[9] The Glamorgan Constabulary's resources were already stretched due to multiple industrial disputes, as there was a month-old strike ongoing in the neighbouring Cynon Valley in addition to the Cambrian Combine dispute.[9] By Sunday, 6 November, Chief Constable Lindsay had assembled approximately 200 imported police officers in the Tonypandy area in anticipation of potential disorder.[9]

The stage was set for a major confrontation between the striking miners and the combined forces of the coal owners, local magistrates, and reinforced police presence, with the potential for military intervention if the situation escalated further.

Riots at Tonypandy

By this time, strikers had successfully shut down all local pits, except Llwynypia colliery.[2] On 6 November, miners became aware of the owners' intention to deploy strikebreakers to keep pumps and ventilation going at the Glamorgan Colliery in Llwynypia. On Monday, 7 November, strikers surrounded and picketed the Glamorgan Colliery to prevent such workers from entering. That resulted in sharp skirmishes with police officers posted inside the site. Although miners' leaders called for calm, a small group of strikers began stoning the pump-house. A portion of the wooden fence surrounding the site was torn down. Hand-to-hand fighting ensued between miners and police. After repeated baton charges, police drove strikers back towards Tonypandy Square, just after midnight. Between 1 am and 2 am on 8 November, a demonstration at Tonypandy Square was dispersed by Cardiff Police, using truncheons, resulting in casualties on both sides.[8] That led Glamorgan's chief constable, Lionel Lindsay, supported by the general manager of the Cambrian Combine, to request military support from the War Office.[9]

Home Secretary Winston Churchill learned of that development and, after discussions with the War Office, delayed action on the request. Churchill felt that the local authorities were overreacting and believed that the Liberal government could calm matters down. He instead despatched Metropolitan Police officers, both on foot and mounted, and sent some cavalry troops to Cardiff.[9][10] He did not specifically deploy cavalry but authorised their use by civil authorities if it was deemed necessary. Churchill's personal message to strikers was, "We are holding back the soldiers for the present and sending only police".[9] Despite that assurance, the local stipendiary magistrate sent a telegram to London later that day and requested military support, which the Home Office authorised. Troops were deployed after the skirmish at the Glamorgan Colliery on 7 November but before rioting on the evening of 8 November.[9]

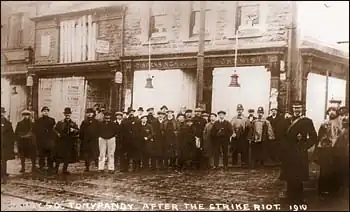

During the evening of rioting, properties in Tonypandy were damaged, and some looting took place.[8] Shops were smashed systematically but not indiscriminately.[9] There was little looting, but some rioters wore clothes taken from the shops and paraded in a festival atmosphere. Women and children were involved in considerable numbers, as they had been outside the Glamorgan colliery. No police were seen at the town square until the Metropolitan Police arrived around 10:30 pm, almost three hours after the rioting began, when the disturbance subsided of its own accord.[9] A few shops remained untouched, notably that of the chemist Willie Llewellyn, which was rumoured to have been spared because he had been a famous Welsh international rugby footballer.[11]

A small police presence might have deterred window-breakages, but police had been moved from the streets to protect the residences of mine owners and managers.[8]

At 1:20 am on 9 November, orders were sent to Colonel Currey at Cardiff to despatch a squadron of the 18th Hussars to reach Pontypridd at 8:15 am.[9] Upon arrival, one contingent patrolled Aberaman and another was sent to Llwynypia, where it patrolled all day.[9] Returning to Pontypridd at night, the troops arrived at Porth as a disturbance was breaking out, and then maintained order until the arrival of the Metropolitan Police.[9] Although no authentic record exists of casualties since many miners would have refused treatment for fear of prosecution for their part in the riots, nearly 80 police and over 500 citizens were injured.[12] One miner, Samuel Rhys, died of head injuries that were said to have been inflicted by a policeman's baton, but the verdict of the coroner's jury was cautious: "We agree that Samuel Rhys died from injuries he received on 8 November caused by some blunt instrument. The evidence is not sufficiently clear to us how he received those injuries." Similarly, the medical evidence concluded, "The fracture had been caused by a blunt instrument—it might have been caused by a policeman's truncheon or by two of the several weapons used by the strikers, which were produced in court."[13] Authorities had reinforced the town with 400 policemen, one company of the Lancashire Fusiliers, billeted at Llwynypia, and the squadron of the 18th Hussars.

Thirteen miners from Gilfach Goch were arrested and prosecuted for their part in the unrest. The trial of the thirteen occupied six days in December. During the trial, they were supported by marches and demonstrations by up to 10,000 men, who were refused entry to the town.[2] Custodial terms of two to six weeks were issued to some of the respondents; others were discharged or fined.

Reaction to riots

In the immediate aftermath of the riots, conflicting accounts of the events circulated throughout South Wales and beyond. Eyewitness reports varied significantly, with some claiming that troops had fired upon miners, resulting in multiple fatalities. These accounts spread rapidly through word of mouth in mining communities, contributing to lasting local narratives about the events. However, according to official records, no shots were fired by military forces during the disturbances.[14] Relations between the deployed troops and the striking miners were reportedly less confrontational than might have been expected, with contemporary accounts describing instances of soldiers and miners engaging in friendly football matches during the period of military presence.[15]

The confirmed casualty from the riots was Samuel Rhys, a miner who died from head injuries sustained during confrontations with police. The circumstances of his death remained a matter of dispute, with the coroner's jury delivering a cautious verdict stating that whilst Rhys died from injuries received on 8 November "caused by some blunt instrument," the evidence was "not sufficiently clear" as to how he received those injuries.[13]

The Tonypandy riots left a profound impact on Welsh cultural memory and found significant expression in Cwmardy (1937), an autobiographical novel by Lewis Jones, who later became a prominent communist trade union organiser. Jones, who had personal experience of mining communities and labour disputes, presented a detailed account of the riots and their social consequences, blending factual elements with literary dramatisation.[16] Cwmardy has been recognised as one of the most important works of Welsh industrial fiction, providing valuable insights into working-class life and the impact of industrial disputes on mining communities.[17][18]

Jones's narrative included dramatic incidents that differed from official records, such as a scene in which eleven strikers are killed by rifle volleys in the town square, followed by organised retaliation against mine managers. His account concluded with the strike ending through the introduction of a minimum wage act, which he portrayed as a victory for the workers. The relationship between Cwmardy and historical documentation has been a subject of scholarly discussion. Some literary critics and historians have emphasised the tension between documentary realism and political allegory in Jones's work, noting its allegedly fictional elements and ideological framework.[19][20]

Other scholars have recognised the novel's cultural and social significance, noting its important role in preserving and transmitting working-class memory of the events and its continuing study as a significant work of proletarian literature.[21]

The industrial dispute that had triggered the riots continued for many months after the November 1910 violence. The strike finally concluded in August 1911, with miners returning to work in early September having been compelled to accept the wage rate of 2s 3d per ton that had been negotiated by William Abraham prior to the commencement of the strike.[2]

Criticism of Churchill

.jpg)

Churchill's role in the events at Tonypandy during the conflict left anger towards him in South Wales that still persists today. The main point of contention was his decision to allow troops to be sent to Wales. Although this was an unusual move and was seen by those in Wales as an overreaction, his Tory opponents suggested that he should have acted with greater vigour.[9] The troops acted more circumspectly and were commanded with more common sense than the police, whose role under Lionel Lindsay was, in the words of historian David Smith, "more like an army of occupation".[9]

The incident continued to haunt Churchill throughout his career. Such was the strength of feeling, that almost forty years later, when speaking in Cardiff during the general election campaign of 1950, this time as Conservative Party leader, Churchill was forced to address the issue, stating: "When I was Home Secretary in 1910, I had a great horror and fear of having to become responsible for the military firing on a crowd of rioters and strikers. Also, I was always in sympathy with the miners..."[9]

A major factor in the dislike of Churchill's use of the military was not in any action undertaken by the troops, but the fact that their presence prevented any strike action which might have ended the strike early in the miners' favour.[9] The troops also ensured that trials of rioters, strikers and miners' leaders would take place and be successfully prosecuted in Pontypridd in 1911. The defeat of the miners in 1911 was, in the eyes of much of the local community, a direct consequence of state intervention without any negotiation; that the strikers were breaking the law was not a factor with many locals. This result was seen as a direct result of Churchill's actions.[9]

Political fallout for Churchill also continued. In 1940, when Neville Chamberlain's war-time government was faltering, Clement Attlee secretly warned that the Labour Party might not follow Churchill because of his association with Tonypandy.[9] There was uproar in the House of Commons in 1978 when Churchill's grandson, also named Winston Churchill, was asking a question, during Prime Minister's Questions, on miners' pay; he was warned by the Labour leader and Prime Minister James Callaghan not to pursue "the vendetta of your family against the miners of Tonypandy".[22][23] In 2010, ninety-nine years after the riots, a Welsh local council made objections to an old military base being named after Churchill in the Vale of Glamorgan because of his sending troops into the Rhondda Valley.[24]

Historiographical debate

The historiography of the Tonypandy riots has been characterised by significant scholarly debate regarding the interpretation of Churchill's actions and their consequences. Historians have offered divergent assessments of whether Churchill's deployment of military forces represented restraint in the face of civil disorder or state intervention that fundamentally altered the balance of power in the industrial dispute.

Welsh historical scholarship

Dai Smith, Professor of History at the University of Wales and native of Tonypandy, has argued that historiographical focus on whether military forces directly engaged strikers has obscured the substantive political consequences of their deployment. In his seminal work "Tonypandy 1910: Definitions of Community", Smith contends that the military presence fundamentally altered the industrial dispute's outcome, ensuring "that the miners' demands would be utterly rejected" regardless of the troops' restrained conduct.[25]

Research by Anthony Mòr O'Brien in the Welsh History Review demonstrated that official correspondence published in Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales had been selectively edited, removing evidence that Churchill advocated the deployment of state violence through police rather than military action.[26] This editorial intervention, O'Brien argues, contributed to the construction of a more favourable historical narrative regarding Churchill's conduct.

Daryl Leeworthy has positioned the Tonypandy events within the broader trajectory of Welsh political development, arguing that the confrontation constituted a foundational moment in the emergence of Welsh social democracy and marked a decisive shift in working-class political consciousness.[27]

Strategic and political consequences

Historians have emphasised that the deployment of military forces, whilst not resulting in direct confrontation, fundamentally undermined the miners' negotiating position. The troops' presence effectively prevented strike action that might have compelled an earlier resolution favourable to the miners, whilst simultaneously ensuring the successful prosecution of strike leaders in Pontypridd during 1911.[9] This strategic deployment has been characterised by scholars as decisive in securing the miners' ultimate defeat.

Jane Morgan's analysis of state responses to industrial unrest identifies Churchill's interventions at Tonypandy as representing a qualitative shift in government policy, whereby "industrial disorder of this kind was seen for the first time as a national emergency, one that required a co-ordinated response, civil and military, from the state."[28] This centralisation of authority over industrial disputes marked a departure from previous practices of local autonomy in policing such conflicts.

Radicalisation and political legacy

The events at Tonypandy contributed significantly to the radicalisation of the South Wales mining community. The deployment of General Nevil Macready—subsequently commanding officer of the Black and Tans during the Irish War of Independence - exemplified what historians have characterised as the state's increasingly militarised approach to industrial relations.[29]

The confrontation catalysed the emergence of more militant approaches within Welsh mining communities, with younger activists influenced by syndicalist organisations such as the Industrial Workers of the World advocating confrontational strategies against mine ownership.[29] This ideological transformation subsequently influenced foundational documents of Welsh labour militancy, including The Miners' Next Step (1912).

The enduring political consequences of Churchill's intervention persisted well into the post-war period. Opposition to honouring Churchill in Wales remained evident as late as 1949, when Cardiff councillors opposed street naming proposals, with one member observing that "Tonypandy men had long memories."[30] Similar sentiments were expressed in 2010 when Welsh local authorities objected to military installations bearing Churchill's name, explicitly referencing his deployment of troops to the Rhondda Valley.[24]

Competing narratives and the "shooting myth"

The Tonypandy riots have become the subject of competing historical narratives, with different interpretations reflecting broader political and historiographical debates about the role of state power in industrial disputes. A persistent popular narrative claims that troops fired upon the miners during the riots.[31][32][33] Contemporary records indicate that no shots were fired by military forces at Tonypandy, and the only recorded fatality was Samuel Rhys, who died from head injuries sustained during confrontations with police.[13]

Josephine Tey referenced this discrepancy in her novel The Daughter of Time, coining the term "tonypandy" to describe instances where "a historical event is reported and memorialised inaccurately but consistently until the resulting fiction is believed to be the truth".[34]

The only bloodshed in the whole affair was a bloody nose or two. The Home Secretary was severely criticised in the House of Commons incidentally for his "unprecedented intervention". That was Tonypandy. That is the shooting-down by troops that Wales will never forget... It is a completely untrue story grown to legend while the men who knew it to be untrue looked on and said nothing.

— Josephine Tey, The Daughter of Time, pp. 110–111

The Tonypandy events continue to generate competing historical narratives and political interpretations. Historians disagree about various aspects of the events, from specific details to their broader significance in British labour history. The events have continued to influence Welsh political discourse well into the twenty-first century, demonstrating how historical events can acquire enduring symbolic importance in debates about state power, labour relations, and national identity.

See also

References

- ^ Evans, Gwyn; Maddox, David (2010). The Tonypandy Riots 1910–11. Plymouth: University of Plymouth Press. ISBN 978-1-84102-270-3.

- ^ a b c d "Tonypandy heritage". Rhondda Cynon Taff Council. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008.

- ^ Williamson, David (13 January 2018). "The towns in Wales where Churchill was loathed". WalesOnline. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The Making of the Welsh Working Class". Jacobin. August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Syndicalism in south Wales: The origins of The Miners' Next Step". libcom.org. 1987. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ a b c "The Cambrian Combine". Northern Mine Research Society. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ "Cambrian Combine Dispute Study - First South Wales Coalfield Project 1972-1974". Archives Hub. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lewis, E.D. (1959). The Rhondda Valleys. London: Phoenix House. p. 175.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Herbert, Trevor, ed. (1988). Wales 1880–1914: Welsh History and its sources. Cardiff: University of Wales Press. p. 109. ISBN 0-7083-0967-4.

- ^ "The Aftermath – Sir Winston Churchill and the Rhondda Rioters". South Wales Police Museum. Archived from the original on 28 September 2004.

- ^ Miller, Claire (28 October 2010). "Did Tonypandy rioters deliberately spare the shop of a rugby legend?". Western Mail.

- ^ "March commemorates centenary of Tonypandy riots". BBC News. 22 September 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ a b c "Blow on the Head - Tonypandy man's death". Evening Express and Evening Mail: Welsh Newspapers Online - The National Library of Wales. 15 December 1910. p. 3. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ Colliery Strike Disturbances in South Wales: Correspondence and Report: November 1910. Home Office. 1911.

- ^ Fox, K.O. (October 1973). "The Tonypandy Riots". Army Quarterly. 104 (1): 77–78.

- ^ L., Jones (1978) [first published 1937]. Cwmardy. Lawrence & Wishart. ISBN 978-0-85315-468-6.

- ^ Smith, Dai (1993). Aneurin Bevan and the World of South Wales. University of Wales Press. pp. 45–67.

- ^ Williams, Chris (1991). "Democratic Rhondda: Politics and Society, 1885-1951". Welsh History Review. 15 (3): 369–396.

- ^ Klaus, Gustav (1985). The Literature of Labour: Two Hundred Years of Working-Class Writing. Harvester Press. pp. 156–178.

- ^ Berry, Ron (1978). "Lewis Jones and the Welsh Industrial Novel". Planet (42): 12–19.

- ^ Pikoulis, John (1986). The Art of William Jones. University of Wales Press. pp. 89–112.

- ^ "Prime Minister Engagements (1978)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 30 November 1978. col. 696. Retrieved 11 April 2022.

- ^ "Winston Churchill". Telegraph (UK). 2 March 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ a b "Churchill name for military base opposed, 100 years on". BBC News. 12 June 2010. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Smith, Dai (1980). "Tonypandy 1910: Definitions of Community". Past & Present. 87: 158–184.

- ^ O'Brien, Anthony Mòr (1994). "Churchill and the Tonypandy riots". Welsh History Review. 17 (1): 67–99.

- ^ Leeworthy, Daryl (2017). "Tonypandy 1910: The Foundations of Welsh Social Democracy". In Outram, Quentin; Laybourn, Keith (eds.). Secular Martyrdom in Britain and Ireland. Palgrave Macmillan.

- ^ Morgan, Jane (1987). Conflict and Order: The Police and Labour Disputes in England and Wales, 1910–1939. Clarendon Press. p. 40.

- ^ a b "The Tonypandy Riots Changed the Welsh Working Class Forever". Tribune. 8 November 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ Smith, Dai (30 August 2022). "The Tonypandy Riots, 1910 - Winston Churchill's Nemesis". International Churchill Society. Retrieved 13 August 2025.

- ^ Barber, Tony (15 February 2019). "Churchill would have relished the uproar over his legacy". Financial Times. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Low, Valentine (14 February 2019). "Tonypandy: the miners' strike that blighted Churchill's career". The Times. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ "Wales: History, Myth and Empire". Institute of Welsh Affairs. 5 December 2015. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ Cox, S. J. B. (1985). "No Tragedy on the Commons". Environmental Ethics. 7 (1): 49–61. doi:10.5840/enviroethics1985716.

Further reading

- Addison, Paul. Churchill on the Home Front 1900-1955 (Pimlico, 1992) pp. 138–145.

- Langworth, Richard M. (2017). Winston Churchill, Myth and Reality: What He Actually Did and Said. McFarland. pp. 39–43. ISBN 978-1-4766-6583-2.

- McEwen, John M. "Tonypandy: Churchill's Albatross," Queen's Quarterly (1971) 78#1 pp. 83–94.

- Morgan, Kenneth O. Rebirth of a Nation: Wales, 1880-1980 (Oxford UP, 1981) pp. 146–153.

- O'Brien, Anthony Mòr. "Churchill and the Tonypandy Riots," Welsh History Review (1994), 17#1 pp 67–99. online

- Shelden, Michael (2013). Young Titan: The Making of Winston Churchill. Simon and Schuster. pp. 20–22. ISBN 9781471113246.

- Smith, David. "Tonypandy 1910: definitions of community." Past & Present 87 (1980): 158–184. online

- Smith, David. "From Riots to Revolt: Tonypandy and The Miners' Next Step," in Trevor Herbert and Gareth Elwyn Jones (eds), Wales 1880–1914 (University of Wales Press, 1988)

- Stephenson, Charles. "Chapter 2: South Wales Strife (2): Tonypandy" in Churchill as Home Secretary: Suffragettes, Strikes and Social Reform, 1910–1911 (Pen and Sword, 2023) ch. 3

External links

- Rhondda—the story of coal pp. 124–126 of 126-page download at Rhondda Cynon Taf Library Service (37mB)

- Carradice, Phil The Tonypandy Riots of 1910 at BBC Wales History, 3 November 2010

- History of the Cambrian Combine miners' strike and Tonypandy Riots

- The Rhondda Riots of 1910–1911 on website of South Wales Police

- Tonypandy 1910 Coalfield web materials from the University of Wales, Swansea, with further reading and external links

- Cambrian Colliery, Clydach Vale. c. 1910 on Welsh Coalmines historical website

- Commemorating the 100th Anniversary A heritage page of Rhondda Cynon Taf Council

- Cambrian Combine miners strike and Tonypandy riot, 1910 - Sam Lowry – A brief history of the background to the dispute, the strike and its outcome

- Did Churchill Send Troops Against Strikers? "Guilty with an Explanation" Churchill's decisions to use troops against strikers prior to WW1

- The towns in Wales where Churchill was loathed How Churchill's reputation was still tarnished 50 years after Tonypandy