The Cloud Messenger (music)

| The Cloud Messenger | |

|---|---|

| Cantata by Gustav Holst | |

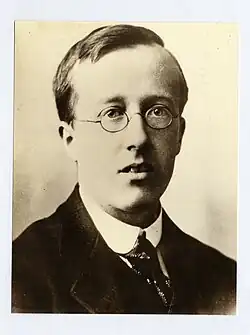

The composer in his mid-twenties, c. 1901. | |

| Librettist | Composer, from an ancient Sanskrit poem |

| Language | English |

| Based on | Meghadūta ('The Cloud Messenger') by the Indian poet, Kālidāsa (c. 4th–5th century CE) |

| Premiere | |

The Cloud Messenger, Op. 30, is a cantata for contralto solo, chorus and orchestra by the English composer Gustav Holst, based on Meghadūta, an ancient Sanskrit poem. Holst worked on it for several years, and it was completed in 1910.[1] After some revisions, it was published in 1912.[2]

The Cloud Messenger was first performed in 1913 at one of the Queen's Hall concerts presented by H. Balfour Gardiner.[2] In 1924, after a concert performance by the Langham Choral Society, a review in The Musical Times referred to the 'elaborate Oriental imagery' of Holst's text, combined with music that 'abounds in beauties'. According to that review, the work is consistent with the composer's Hymns from the Rig Veda, while looking ahead to the style of his Hymn of Jesus.[3]

On 19 November 2016, it received its first public performance since the 1930s, with the Tonbridge Philharmonic and Choral Society conducted by Matthew Wilks, and the mezzo-soprano Linda Finnie.[4]

Based on an ancient lyric poem

Meghadūta (Bengali: মেঘদূত, literally Cloud Messenger) is a lyric poem written by the great Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa (c. 4th–5th century CE).[5]

It describes how a yakṣa (a nature spirit, or demi-god), after neglecting his daily duties, has been exiled for a year to a remote mountain by his master Kubera, the god of wealth. After some time passes, the lonely yakṣa tries to convince a passing cloud to take a message of love to his wife back home.[5]

The yakṣa describes the beautiful sights and sounds the cloud will experience on its northward journey – arrays of colourful blossoms, the sweet sounds of birds, and awe-inspiring rivers and mountains.[5]

Along the way, pausing at the temple of Lord Shiva, the cloud's rumblings will act as the tabor (drum) at evening prayers. At the city of Alakā in the Himalayas, the yakṣa hopes that the cloud will deliver the message to his wife, and then return with a reply from her.[5]

The poem was first translated into English in 1813 by Horace Hayman Wilson.[6]

Holst initially based his text on a version of the Meghadūta by R.W. Frazer, which the composer had read in the 1890s. In 1907, he purchased a version edited by Pandit Nabin Chandra Vidyaranta. Holst's copy is now in St Paul's Girls School, where he taught music.[7]

Holst scholar Raymond Head observes that the composer took care to avoid including any of the erotic elements from the original Sanskrit texts.[7]

Movements

- Prelude

- O thou, who com'st from Heaven's king

- In the city of the Great God

- Bringer of rain

- Rushing northward

- See how all greet thee

- Behold the villages

- As the rain descends

- Tarry not, O cloud, tarry not

- Tarry not, O cloud

- And hark!

- Thou hast reached the snowy peaks

- And see! The Great God himself

- Chorus (Moderato maestoso)

- When the dancers are weary

- Wait near her flower-covered window

- The Message (I, the bringer of the rain)

- 'Beloved!'

Hindu philosophy

As a young man, Holst became interested in Hindu philosophy, and in 1899 studied Sanskrit literature at University College in London.[9] Holst drew inspiration from the Hindu tradition a number of times, with notable examples being, along with this work, Hymns from the Rig Veda, and the opera Sāvitri.[7]

In 1919, writing in The Musical Times, Edwin Evans, when reviewing the composer's ongoing development, described this as Holst's 'Sanskrit' period.[1] In the 1980s, in Holst and India: 'Maya' to 'Sita', Raymond Head described it as Holst's 'Indian' period.[7]

According to Imogen Holst, her father began exploring Indian culture and history after reading the book Silent Gods and Sun Steeped Lands by R. W. Frazer.[7]

Recordings

| Performers | Year | Label |

|---|---|---|

| Della Jones, contralto; London Symphony Chorus; London Symphony Orchestra; Richard Hickox, conductor. | 1990 | Chandos |

| (Adapted for chamber ensemble) Caitlin Goreing, alto; King's College London Chapel Choir; The Strand Ensemble; Joseph Fort, arranger & conductor. | 2020 | Delphian |

Sources: WorldCat and Apple Classical

Score

References

- ^ a b Evans, Edwin (1919-12-01). "Modern British Composers. VI.-Gustav Holst (Concluded)". The Musical Times. 60 (922): 657–661. doi:10.2307/3701919. JSTOR 3701919.

- ^ a b Capell, Richard (1927-01-01). "Gustav Holst: Notes for a Biography (II)". The Musical Times. 68 (1007): 17–19. doi:10.2307/913569. JSTOR 913569.

- ^ "London Concerts". The Musical Times. 65 (973): 257–261. 1924. ISSN 0027-4666. JSTOR 913086.

- ^ "Wayback Machine" (PDF). www.holstsociety.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-03. Retrieved 2025-08-17.

- ^ a b c d ROYCHOWDHURY, KRISHNA CHANDRA. “Kalidasa’s Imagery in ‘Meghaduta.’” Indian Literature 19, no. 2 (1976): 92–118. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24157268.

- ^ Ireland, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and (1834). Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press for the Royal Asiatic Society.

- ^ a b c d e Head, Raymond (1988). "Holst and India (III)". Tempo (166): 35–40. doi:10.1017/s0040298200024293. ISSN 0040-2982.

- ^ The Cloud Messenger, H111 recording by The Choir of King's College London — Apple Music Classical, retrieved 2025-08-11

- ^ Huismann, Mary Christison (2011-04-26). Gustav Holst: A Research and Information Guide. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-84527-8.