The Big Wave (film)

| The Big Wave | |

|---|---|

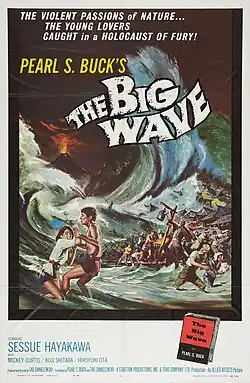

Theatrical release poster by Reynold Brown | |

| Directed by | Tad Danielewski |

| Screenplay by | Pearl S. Buck Tad Danielewski |

| Based on | The Big Wave by Pearl S. Buck |

| Produced by | Tad Danielewski |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Ichio Yamazaki |

| Edited by | Akikazu Kono |

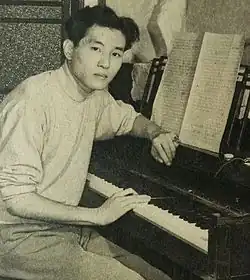

| Music by | Toshiro Mayuzumi |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Allied Artists Pictures |

Release dates | |

Running time | 98 minutes (original) 73 minutes (U.S.) |

| Countries | United States Japan |

| Language | English |

The Big Wave [a] is a 1961 melodrama film based on the 1948 novel by Pearl S. Buck. The film was directed and produced by Tad Danielewski from a screenplay co-written with Buck, and stars Sessue Hayakawa, Mickey Curtis, Koji Shitara, and Hiroyuki Ota. The story follows two boys, Yukio (played by Ota and Curtis) and Toru (Shitara and Ichizo Itami), growing up in a coastal village that is often threatened by natural disasters. Their friendship is strained when both develop feelings for the same ama girl, Haruko (Reiko Higa).

After working together on a 1956 television adaptation of The Big Wave for NBC, Buck and Danielewski formed the independent production company Stratton Productions. The film adaptation began development in early 1960. Buck visited Japan in May 1960 for the initial meetings but returned to the United States that June after her husband's death, briefly pausing her involvement. During pre-production, Japanese co-producer Toho appointed a Japanese co-director, who ultimately left due to conflicts with Danielewski. Principal photography lasted from September to November 1960, on location in Japan. It became a pioneering American-Japanese co-production and the film debut of both Buck and Danielewski. Buck later authored a memoir, A Bridge for Passing (1962), recounting her experiences during the film's production.

The Big Wave was screened in Hirosaki and Niigata in 1961, and released in the United States on April 29, 1962. It garnered mostly favorable reviews from Western critics, with praise for its acting, story, special effects, and cinematography, but criticism for the slow pacing. A lack of existing contemporary documentation has made its box office total, as well as exact screening dates in Japan, unknown. The film has since become largely unavailable to the general public. A print owned by the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute was screened in Unzen, Nagasaki on October 29, 2005, but has since been disposed of. As of 2018, the Library of Congress owned the only known remaining viewable print of the film.[1]

Plot

Yukio, a farmer, and Toru, a fisher, are two young friends who live in a coastal village on a Japanese island. One day, they travel to the beach and meet a young pearl diver (ama) named Haruko, who gifts them an abalone and shows them her diving skills. Yukio's sister, Setsu, watches them, deciding she has a liking for Toru and wants to become an ama to impress him like Haruko.[1]

On the village's annual shark hunting day, Toru, his father, and most of the villagers prepare for their trip, but are interrupted by the village leader, known as the "Old Gentleman", who warns them of a tsunami that he predicts will destroy the village, as it happened thirty years ago on the same day. He urges everyone to flee to the hills. The villagers disregard the Old Gentleman's claims and continue with their daily practices. That night, while Toru is staying at Yukio's house on a farm on the outskirts of the village, the nearby volcano erupts, resulting in a massive wave destroying the village and killing almost everyone in it, including Toru's family. Toru witnesses the entire tsunami and faints, devastated by the loss of his parents. The wealthy Old Gentleman offers to adopt Toru, but Toru instead decides to live with Yukio's family (who live in poverty).[1]

A decade later, Toru is adopted by Yukio's parents, and they live at their house with Setsu, who still has a crush on Toru. He remains audacious and has been saving money to buy a boat, and receives an offer to purchase a boat from Haruko, who also has a crush on him. One day, Yukio and Toru go shark hunting with Setsu and Haruko. The two boys realize they both have developed feelings for Haruko over time. A fight soon breaks out between the two girls over who can be in a relationship with Toru, with Haruko unsuccessfully attempting to drown Setsu.[2] Yukio and Toru ultimately get involved. After Toru throws Haruko aside, Yukio becomes enraged and assaults Toru. The fight concludes when Yukio reveals he loves Haruko, and Turo says he wants Setsu; the girls agree to marry them, respectively.

Toru and Setsu return to the now-rebuilt village and talk about their plans to get married and go fishing, to which the Old Gentleman overhears. The elder resents the ocean since his son was killed while fishing three decades prior, and instead offers the couple the largest farm in the area, adding that he would not warn them of any more tsunamis if they refuse. Nonetheless, they refuse, but suggest he should continue using his wisdom for good and still warn them anyway, to which he agrees.[3]

Cast

- Sessue Hayakawa as the Old Gentleman

- Ichizo Itami as Toru

- Koji Shitara as young Toru

- Mickey Curtis as Yukio

- Hiroyuki Ota as young Yukio

- Rumiko Sasa as Setsu

- Judy Ongg as young Setsu

- Reiko Higa as Haruko

- Sachiko Atami as young Haruko

- Heihachiro Okawa as Yukio's father

- Chieko Murata as Yukio's mother

- Tetsu Nakamura as Toru's father

- Frank Tokunaga as Toru's grandfather

- Shigeru Nihonmatsu as the old servant

- Noriko Sengoku as Toru's mother

Cast listing taken from the film's pressbook.[4]

Production

Development

While working at NBC in the mid-1950s,[5] Tad Danielewski suggested to author Pearl S. Buck a televised adaptation of her 1948 novel The Big Wave, with Buck writing the script.[6] Her script was ultimately adapted for an episode of the anthology television series The Alcoa Hour.[7] Shot in color[6] under the direction of Norman Felton, the episode starred Rip Torn and Robert Morse as the two Japanese village boys, and Hume Cronyn as the Wise Gentleman.[8] It aired on NBC in September 1956, to acclaim from New York-based critics at the time, with The New York Times highlighting Buck's script.[1] Buck said she was "only moderately pleased" with the episode itself, noting her resentment towards how it featured white actors playing Asian characters.[6] Danielewski was also disappointed that he did not end up directing the adaptation of The Big Wave,[6] but later worked with Buck once again by directing an adaptation of Buck's book The Enemy as an episode of Robert Montgomery Presents,[5] which starred Shirley Yamaguchi.[6] Following the episode's success, Buck and Danielewski became close friends.[5]

In 1957,[9][10] Buck and Danielewski founded the independent production company Stratton Productions, which they named after Stratton Mountain.[11] The company initially worked on stage productions before transitioning to film. After several unsuccessful plays, Danielewski proposed adapting The Big Wave into a film in early 1960,[12] and insisted on filming it in Japan to reflect the story authentically.[13] Buck, who served as the co-writer and executive producer,[14] decided to use this as an opportunity to foster U.S.-Japan cultural understanding through its production.[15] She indicated that the decision to make the film in Japan was made in April 1960.[16] Development of the film was first disclosed in the May 4, 1960, issue of Variety.[14] On May 11, the Motion Picture Exhibitor reported that Allied Artists Pictures president Steve Broidy revealed that his company would acquire The Big Wave for release. It was reportedly set to be filmed in color and CinemaScope at that time.[17]

Buck visited Tokyo on May 24 and held the first meeting for the film's production there; the Associated Press noted that it was conveniently the same day as a tsunami resulting from the 1960 Valdivia earthquake hit Northern Japan.[18][19] She traveled back to the United States that June after being informed that her husband, Richard J. Walsh, had died during her absence. Although this briefly deferred her involvement, she returned to Japan to complete negotiations shortly thereafter.[14] The film ultimately became Danielewski's feature directorial debut,[20] and Buck's film debut.[14][b]

"The book, of course, had to be put into new form. The Big Wave is a simple story but its subject is huge. It deals with life and death and life again through a handful of human beings in a remote fishing village on the southern tip of the lovely island of Kyushu, in the south of Japan. The book has always had a vigorous life of its own. It has won some awards in its field, it has been translated into many languages, but never into the strange and wonderful language of the motion picture. To use that language was in itself adventure, not words now, but human beings, moving, talking, dying with courage, living and loving with even greater courage. I am accustomed to the usual arts. I have made myself familiar with canvas and brush, with clay and stone, with instruments of music, but the motion picture is different from all these. Yet it, too, is a great art. Even when it is desecrated by cheap people and cheap material, the medium is inspiring in its potential."

— Pearl S. Buck, A Bridge for Passing (1962)[21]

The script of The Big Wave, co-written by Buck and Danielewski, was predominantly faithful to the novel. The pair expanded largely on the dialogue between the two protagonists Yukio and Toru, who in the original novel were named Kino and Jiya respectively. Setsu was, in the novel, depicted as more mischievous than she is portrayed as emotionally fragile in the film. The film's opening centers on ama divers, as Buck felt this would emphasize their importance in the Japanese coastal community; she had previously made no mention whatsoever of ama in the novel.[1]

Pre-production

Buck and Danielewski, representing Stratton Productions, reached an agreement with the Japanese company Toho. The deal allowed Allied Artists to own the film's distribution rights in all regions except Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, which were given to Toho in exchange for providing special effects director Eiji Tsuburaya and four actors.[14] Buck explained why Toho hired all the Japanese cast and crew for her and Danielewski:

Toho said they would give us full cooperation 'if we would behave like Japanese', which we did. By that they meant that we would pay Japanese prices and not upset the local wage scale. We didn't want to upset conditions here. If a Japanese company came to the United States it should conform to our standards."[22]

Around 200 people auditioned for the thirteen main roles in the film.[22] The American crew were intent on finding Japanese actors who could speak English as they believed this would make the film more universally appealing.[10] Danielewski believed that actors who often appeared in Japanese musical comedies were the best for the roles in the film as they had already been familiarize with Tin Pan Alley and trained to sing in English occasionally. He reportedly had to teach some of the Japanese cast the distinction between "l" and "r" for the film. Danielewski later described the cast as "the kindest, sweetest, hardest working, most wonderful people I have ever been associated with."[22]

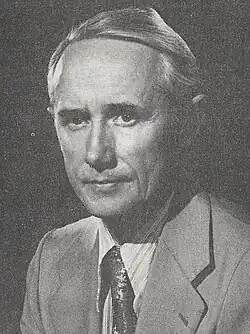

.jpg)

A press conference was held in Tokyo in late May 1960 to disclose pre-production details on the film; Buck and a Toho executive were among those in attendance.[23] Casting negotiations had only begun a few weeks prior, and none had been finalized before the start of the conference. However, word soon reached Buck and the others that Sessue Hayakawa, at the time the most famous Japanese actor in the Western world,[24] had just become the first to secure a role in the film fully, and they went forth to inform the press as the conclusion of the conference.[25] Hayakawa had been working in Hollywood and Japan for decades and likely considered his appearance in The Big Wave as fulfilling his dream of starring in a co-production between the two countries.[1] His wife, Tsuru Aoki, was also set to have a role, as reported in August 1960.[14][c] The Los Angeles Times remarked that the couple had starred in a similar American film, The Wrath of the Gods (1914).[26]

All the adult Japanese cast were well-known in Japan, except Reiko Higa, who Buck said was "chosen especially for the ferocious abalone diving girl".[24] Higa previously appeared in the American film Joe Butterfly (1957).[27] Itami, who played Toru, was an employee of Daiei Film and the company's president, Masaichi Nagata, personally permitted his appearance via a courtesy call with Buck.[28] Setsu was originally set to be played by Kyoko Takahashi, an actress who had worked for Toho's rivaling film company Toei, according to Japanese outlets.[29] However, she was ultimately replaced by Rumiko Sasa from Toho, leaving Takahashi and the Japanese media discouraged.[14][29] Variety attributed the casting change to Takahashi possibly experiencing contractual obligations.[29]

While the Japanese production manager was helping find cast members, Buck, Danielewski, and their assistants went location scouting around Japan. They intended to find a location close to Tokyo as they wanted to remain close to the studio, focused mostly on finding an active volcano and landslides.[30] In May 1960,[31] they traveled to the Japanese island of Izu Ōshima, which Buck found was an easily accessible travel by boat that usually would only take a few hours to reach, and was abroad with fishing villages making it an ideal location for them.[30] Unzen, where Buck had visted during her youth, was also decided to use as a filming location.[2] By late August, the scouting team, without Buck, had found additional locations for the film such as a beach, farm, and the village's houses.[32]

During location scouting, Buck realized the film's tsunami scene was beyond her team's level of expertise and could only be achieved through special effects, which she knew very little about. To her relief, she was soon informed that Toho had what was considered the best special effects team in the world, led by Tsuburaya. Soon after being assigned to the project, Tsuburaya met Buck and the additional co-producers in an office and presented his sketches of the tsunami. Buck described the sketches as "startlingly accurate water colors of the rising horizon, the onrushing wave, and the towering crash of the crest." During the meeting, Tsuburaya also announced plans to recreate the fishing village depicted in miniature form, which he would achieve by taking his cameraman along with him and photographing "everything" for reference.[33]

I know how to behave like this in my own country. I will not behave like this in Japan. I must ask that the Japanese director be removed.

Towards the end of pre-production, Toho appointed a Japanese director to co-direct the film with Danielewski.[35] During a meeting with the famed Japanese director (unspecified in Buck's accounts), who was aided by an interpreter, Buck, Danielewski, Curtis, and Itami began discussing a scene Danielewski wanted Curtis and Itami to improvise. Upon Danielewski telling the Japanese director about how he wanted the scene to play out, the Japanese director began writing on paper how he would like the scene to be and present it to Danielewski and Buck. Danielewski was frustrated as he did not want written instructions for Curtis and Itami for the particular scene, and the two actors ultimately sided with him on the matter.[36] Thereafter, Danielewski warned that he would quit directing and return to New York if the Japanese director was not removed, to Buck's shock.[37] The interpreter informed Danielewski that the Japanese director is a well-regarded man locally, and disrespecting him could have dire consequences.[38] Buck apologized to the director and interpreter, stating that "If we had just gone on location, it would have been worse", to which the director agreed and expressed compassion.[39] After the dispute, the Japanese filmmaker resigned from working on the film.[40]

The cast and central crew members met together at the Imperial Hotel on September 8, 1960. The Japan Times reported that the attendance of Curtis, Sasa, Higa, and composer Toshiro Mayuzumi hereby disclosed their involvement in the film, and that it would be shot around Nagasaki.[41]

Filming

Principal photography

Principal photography commenced on September 15, 1960,[42] in Nagasaki Prefecture.[43][44] Since Buck's story was inspired by the 1792 Unzen landslide and tsunami,[1][45] the film adaptation was mostly filmed on the island of Kyushu[46] around Mount Unzen.[1] Shooting locations in the area included the towns of Obama, Chijiwa (both now part of Unzen City),[1][45][47] and another formally known as Kitsu. Buck identified the latter as the fishing village that was entirely swept away by the 1792 tsunami and later rebuilt.[48][49] Ichio Yamazaki served as the cinematographer, shooting in black-and-white;[50] his previous credits include Akira Kurosawa's The Lower Depths (1957) and The Hidden Fortress (1958).[51]

The film's production in Japan garnered significant media attention, partly due to Buck's popularity there. Locals warmly welcomed the American crew during filming in Japanese towns, where they were closely observed with keen interest. To achieve authenticity, most interior scenes were filmed in the actual homes of generous Obama residents rather than on sets. Footage was captured in real Japanese fishing villages, with some residents participating as extras.[1] Unzen's Chijiwa Beach was also used for several sequences.[10] Japan-based assistant director Joe Markaroff, who worked on many American productions in Japan, said that the villager's leader allowed the crew to shoot on the beach in exchange for a three-dollar can of seaweed.[52]

Itami's schedule prevented him from working on the film for the first couple of weeks of photography. During his absence, his wife, Kazuko Kawakita, served as an assistant to the American crew, as she could speak English and had studied in Europe.[53] Kawakita's mother, Kashiko, was also involved in the making of the film, and a print was later held at her film foundation, the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute.[1]

Buck supervised filming[d] and found working on the film enjoyable and a form of escapism, expressing that she was still overwhelmed by grief due to her husband's recent death. However, according to biographer Peter Conn, Buck privately confided that she found her husband's death a source of relief.[55] While filming in Obama, Buck stayed in a fisherman's hut and employed a shipwrecked Chinese refugee woman as her maid. Speaking fluent Chinese, Buck surprised the woman, who knew neither English nor Japanese, with a conversation on their first day together.[56][57] In her excess time, Buck met several Japanese celebrities, including Miki Sawada, the founder of an orphanage and adoption agency for American-Japanese mixed children.[55][e] Buck also wrote letters that were later assembled, at the encouragement of Allied Artists executives, into a book titled A Bridge for Passing, which detailed her experiences during the making of the film.[56] The memoir was later published as a book on April 2, 1962.[58]

Although most of the cast was moderately fluent in English, Sasa struggled to learn the language and memorize her lines, describing her nightly pronunciation lessons as the "hour of terror". Danielewski's wife served as the dialect coach, and actress Yoshiko Yamaguchi visited the set to support Sasa. While generally compliant with directions, Sasa refused a request during a beach-running scene to roll up the sleeves of a red undershirt worn under her yukata, arguing it was not a Japanese custom and would misrepresent her culture abroad. She also observed that Danielewski seemed inexperienced, avoided storyboards, preferring to improvise scenes on location, and employed fewer assistant directors than typical in Japanese films. Sasa later stated that she "didn't sense any talent in the director".[59]

A scene captures the annual shark hunt near Obama[60] and Chijiwa,[61] conducted to safeguard the local fish populations. Using bait fish, around 200 fishing boats trapped sharks in a vast net, described by Buck as seemingly the world's largest and strongest. The boats encircled the sharks, and once the net was full, hundreds of men on the beach hauled it ashore and clubbed the sharks to death. They used most of the shark meat for food, with the remains also processed into oil and fertilizer.[62] The hunt yielded 120 sharks, a significant increase from the single shark caught the previous year. Buck admired the boat fleet but found the sharks' killing unsettling.[2] While the hunt was ongoing, Buck, Hayakawa, and 15-year-old actress Sachiko Atami were on a boat together watching filming. At one point, a four-foot-long shark escaped the net and leapt into their boat near Atami, prompting Buck to scream. Hayakawa then swiftly grabbed the shark by its tail and threw it back into the sea, likely saving Atami from serious injury.[60]

Controversy surrounded the filming of the ama divers.[63] A Japanese assistant who helped make the film's underwater footage was outraged with how the ama were initially portrayed in Buck's script, calling it "sexist". After threatening to quit if it was not revised, he was eventually allowed to rewrite a scene featuring the ama himself.[1] The American co-producers considered filming the ama in their regular clothing, often solely a Japanese undergarment,[27] unacceptable and demanded they be filmed wearing brassieres instead.[63] The divers refused to wear bras for the film at first, considering it improper.[14] Two versions of the ama scenes were ultimately shot, with one for American audiences wherein the ama wear brassieres.[13][14][27]

Weather conditions resulted in several delays, leaving the villagers and crew frustrated. After a twelve-hour day on location at a farmhouse, most of which the crew had waited for the rain to end in order to shoot there, Yamazaki fell onto some rocks at the base of a paddy field once filming had concluded and had to be hospitalized.[64] His doctor reported that he had not fractured any bones, but put Yamazaki's right arm in a sling.[64] However, Yamazaki refused to remain at the hospital and went back to the hotel with Buck and the other crew members shortly thereafter due to his determination to continue filming.[64] Other issues that occurred during photography at the farm include the crew having to simulate rain using a bamboo with holes which they tipped water into due to a sudden change in weather,[65] a duck brought in to be Setsu's pet as per the script being larger than expected, and a rampant dog chasing chickens disrupting filming.[66][67]

A Japanese holiday delayed filming by at least three days, forcing all of Hayakawa's remaining scenes to be shot in a desert on the final day of his contract.[68] During breaks, Hayakawa typically slept, provided with cushions and a pillow, or listened to a fight on a transistor radio to cope with the heat under the makeup. His make-up man applied iced towels to his wrists and neck and maintained his fake beard, which was at risk because Hayakawa often smoked large cigars.[4]

The crew traveled back to Tokyo in October, preparing to film the last scene on location at Izu Ōshima. Buck commented that the volcano had recently been active and had affected the area slightly. They were rushing to complete filming to meet deadlines, but the pilot refused to fly to Ōshima on the initially planned day, and they ventured there by steamer instead, wary of potential typhoons.[31] Two days were spent on the island for photography; guards standing on the edge of Mount Mihara's crater forbade them from accessing due to its recent activity, but they managed to convince them to let them pass.[69] Yamazaki, Danielewski, and assistants descended into the crater carefully for the footage.[70] Five days after they finished filming and had returned to Tokyo, Mount Mihara erupted.[71] Filming concluded circa late November.[f]

Special effects

The film's special effects were directed by Eiji Tsuburaya,[33][47][73][g] with the help of Sadamasa Arikawa, Akira Watanabe, and Teruyoshi Nakano.[1][4][59]: 1 While the crew was filming in Obama, Tsuburaya was staging the tsunami scene at Toho Studios in Tokyo. Buck stated that "twice he had come to Obama to consult and to take hundreds of pictures of Kitsu and the empty beach beyond. We knew that we were in safe hands, the tidal wave would be perfect, but we could not see it until we returned to the city. Ours was the task of creating the approach to the wave, and the recovery from it."[76]

Tsuburaya's effects were the final section of the film to be completed. In A Bridge for Passing, Buck described the last day of filming: "The famous special-effects artist was waiting for me, debonair in a new light suit and hat and with a cane. He had the confident air of one who knows that he has done a triumphantly good job, and after a survey of the scene I agreed with him. In a space as vast as Madison Square Garden in New York, which is the biggest place I can think of at the moment, he had reconstructed Kitsu, the mountains and the sea. The houses were three feet high, each in perfect miniature, and everything else was in proportion. A river ran outside the studio and the rushing water for the tidal wave would be released into the studio by great sluices along one side. I looked into the houses, I climbed the little mountain, I marveled at the exactitude of the beach, even to the rocks where in reality I had so often taken shelter. The set was not yet ready for the tidal wave. That I was to see later on the screen in all its power and terror. I had seen everything else, however, and I said farewell, gave thanks, and went away."[71][67]

Music

Mayuzumi volunteered to write the score, after meeting Buck and gifting her a copy of his 1958 symphony titled Nirvana.[77] He told Buck that he envisioned providing a score that sounded "really romantic, not Wagnerian romantic, strong and delicate together, with contemporary Oriental philosophy. "[78] After writing the film's score, Mayuzumi was set to travel to New York and write music for the New York City Ballet Orchestra.[78] Ultimately, Mayuzumi was allegedly not in Japan at the time of post-production, and the majority of the score was composed by Tōru Takemitsu and Riichirō Manabe, according to the latter.[79] The score is, however, credited to Mayuzumi, with Hiroshi Yoshizawa conducting it.[80]

A song was included in the film to reflect its focus on youth, at Mayuzumi's request.[81] Intending it to be "like the sunrise, young and fresh and full of hope",[81] he wanted to compose it and have Buck write the lyrics, but Buck declined.[81] The song, titled "Be Ready at Dawn", ultimately featured lyrics written by Danielewski,[80] and was sung by Curtis.[1]

Post-production

During post-production, a third of the film's audio was re-recorded under Danielewski's supervision.[22] Editor Lester A. Sansom of Allied Artists was involved in post-production.[14] Two edits of the film were created, with the original having a runtime of 98 minutes while the American version ran for 73 minutes.[74][75] Toho's subsidiary Towa may have dubbed the film into Japanese as well, as reported on May 23, 1961.[82]

Release

The Big Wave was previewed for Allied Artists executives in Hollywood, Los Angeles circa late December 1960, to positive reactions.[14][83] Though the film was never released throughout Japan, it was shown at Hirosaki's National Theatre and Niigata's Toho Theater in 1961. Due to the absence of contemporary reports, the dissolution of Stratton Productions and Allied Artists, and Toho's lack of pertinent records, the precise screening dates in Japan and the film's box office total remain unknown.[1] As late as 1970, Buck commented that Toho still owned a complete print of The Big Wave and hoped they would distribute it someday since she was disappointed that Allied Artists had not done so.[84] At least three Western critics had also reviewed the film by May 1961.[85]

In the United States, the film opened to audiences with a roadshow theatrical release in April 1962.[86] Contemporary sources list the official release date as April 29.[14][80][87]: 107 Reynold Brown made the poster for its release.[88] Allied Artists frequently showed it as the second feature in a double bill, pairing it with films like The Bridge,[89] Rider on a Dead Horse,[90] Convicts 4 (as Reprieve),[91][92] and The Phantom of the Opera[50] in 1962, and The Day of the Triffids[93] and El Cid[94] in 1963. Its Pennsylvanian state premiere took place at Bernard Haines' Selvil Theater in Sellersville on October 17, with Buck and Danielewski present.[95] Buck's son Edgar Walsh, who was serving the United States Army at the time, saw the film at Fort Dix in New Jersey. He recalled: "That was the first movie I ever saw the audience get up and leave".[96] It was also shown at Mexico City's Cine Paris theater on February 12, 1963, under the title Tifón en Japón (transl. Typhoon in Japan).[97] Nevertheless, Buck biographers Nora B. Stirling, Ann La Farge, and Warren Sherk claim that The Big Wave was never released; Stirling and Sherk asserted that no film distributor wanted to release the film, and its only reported screening was a private one for Buck's friends near her home in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.[12][98][99]

According to Boxoffice, The Big Wave overperformed at the American box office, but an estimate could not be provided due to inconclusive reports.[87]: 33 Variety reported that the film grossed roughly $15,000 at the Metropolitan Theatre in Boston during a week in May 1962,[100] US$7,500 at the Fox Theatre in Detroit during a week in July,[101] $4,000 at the Lafayette Theatre in Buffalo during a week in August,[102] and $8,000 at the Golden Gate Theatre in San Francisco during the first week of September.[103]

From September 1963[104] to March 1977,[105] it was occasionally shown on television in the United States. Sasa's husband, Osami Nabe, recounted a friend of his praising Sasa’s English proficiency after seeing the film on U.S. television in the 1970s, though Sasa believed her voice was likely dubbed for international audiences.[59]

In recent years, the film has become largely unavailable to the general public, partly due to copyright intricacies preventing any repairs or releases from taking place in Japan.[1][h] In 2004, a group of residents from Minamitakaki District, Nagasaki began negotiating with the film's American copyright holder to screen it as part of a celebration for the October 2005 merger of seven towns in the region (including two of its filming locations) into Unzen city.[45] It was ultimately screened at Unzen Memorial Hall on October 29, 2005, with Ongg in attendance.[47][59] The print shown there was owned by the Kawakita Memorial Film Institute, but has since been discarded due to deterioration.[1] As of 2018, the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo also held a print, but it was in poor condition and therefore could not be projected. Thus, the Moving Image Section of the Library of Congress owns the only known remaining watchable print of the film, which they have preserved and can be viewed only within the library.[1]

Reception

The May 1961 issue of Consumer Bulletin reported one critic giving the film a "B" rating (suggesting they did not directly recommend or condemned the film) while another two rated it "C" (indicating the reviewers did not recommend it).[85] The following year, positive reviews from critics were reported.[50][107] Stratton Productions claimed The Big Wave and Danielewski's succeeding film No Exit (1962) received "international acclaim", providing a single review of the former and five reviews of the latter as proof.[50]

Critics consistently praised the acting and casting choices.[50][108][109] A Motion Picture Exhibitor reviewer highlighted Hayakawa’s standout performance, whearas they viewed the cast as all-else complete unknown in the Western world.[109] Boxoffice commended the all-Japanese cast's delivery of English dialogue, specifically singling out Hayakawa and Curtis.[110] Michael S. Willis of the San Francisco Chronicle remarked the on-location shooting with the use of an all-Japanese cast "create a feeling of uncontrived reality", though he found the Japanese accents occasionally distracting.[50] In a retrospective review, author Thomas S. Hischak similarly felt the performances were decent, contributing to the film’s authentic atmosphere.[7]

The production values garnered recognition. Willis lauded cinematographer Yamazaki’s work, underscoring the authentic portrayal of elderly villagers.[50] The cinematography and special effects were also accentuated by the French-language publication Mediafilm.[108] The Motion Picture Exhibitor regarded the tidal wave scene as a decent showcase of the Japanese film industry's skill in creating realistic miniature sets. They also hailed the shark hunt sequence and the editing, noting that substantial cuts for the U.S. release impacted the final product.[109]

Reviewers offered varied perspectives on The Big Wave's market potential and overall impact. The Motion Picture Exhibitor critic thought the film was captivating but saw the story as only appealing to art house audiences due to its niche qualities and leisurely pacing.[109] In contrast, Boxoffice suggested it had broader potential, capable of succeeding in both art house and mainstream markets, due to its compelling story and Buck’s reputation.[110] Willis described it as "not a masterpiece, but it achieves quite admirably what it sets out to do", considering it a "fine, gentle counterpoint" to The Phantom of the Opera, its double-feature counterpart.[50] Mediafilm highlighted it as a "work full of sensitivity and human tenderness".[108] Reviewing the 60-minute televised version, Steven H. Scheuer, Leonard Maltin, and Blockbuster Entertainment noted its slow pacing; additionally, Scheuer praised the acting.[111][112][113] Blockbuster Entertainment described the film as "Leisurely paced and quite interesting, really".[114] Hischak echoed these sentiments by calling its overall narrative restrained, engaging viewers more intellectually than emotionally.[7]

Legacy

The Big Wave is considered culturally and historically significant, but how widespread its social impact was at the time remains unknown.[1] It became a pioneering cinematic co-production between the United States and Japan; Buck claimed it was notable as the first film with an American production company working entirely in Japan with a major Japanese company and a partially Japanese crew.[115] Two other U.S.-Japan co-productions also featuring Tetsu Nakamura among the cast were, however, produced in the 1950s: Tokyo File 212 (1951) and The Manster (1959), predated the film.[116] Following The Big Wave was Frank Sinatra's None but the Brave (1965), also co-produced by Toho, starring Nakamura, and featuring special effects by Tsuburaya.[73] The film is also regarded as an early disaster film as well as an early example of how natural disasters in Japan are perceived abroad.[73]

Since its release, the film has gradually faded into obscurity.[1] In November 2022, The New York Times Book Review asked readers to identify which of Buck's books had received both a film and a television adaptation. Only 24% of over 7,000 participants correctly answered The Big Wave.[117]

Notes

- ^ Japanese: 大津波, Hepburn: Daitsunami

- ^ Buck had previously sold the film adaptation rights to three of her books, which became The Good Earth (1937), Dragon Seed (1944), and China Sky (1945). Per her: "They have a peculiar system in Hollywood; they won't let the author have anything to do with the film. I didn't like some of the things that were done, and so I decided to sell no more of my books until I could have some control over the filming."[13]

- ^ Aoki is not listed in the final credits, but was later mentioned once again to be among the cast in a January 1961 report by The New York Times.[22]

- ^ Per biographer Nora B. Strling: "Pearl's presence would lend prestige and support. Actually she was also there because she was suffering the malaise of jealousy, and justified or not, was suspicious and unhappy. Dorothy Olding received word that Pearl was there to prevent any American-Japanese incidents that might roil international relations."[54]

- ^ Buck also visited Korea, discovering many more children of Asian mothers and U.S. military fathers, who faced discrimination and were often orphaned. She later coined and popularized the term "Amerasians" for these children.[55]

- ^ American publications first reported that it had ended in December.[14] However, Buck stated in an editor's note for The Japan Times published on November 20, 1960, that she was returning to the U.S. and entrusting Danielewski to stay for post-production since filming had just finished.[72]

- ^ The American Film Institute and Stuart Galbraith IV erroneously credit the special effects to "Kenji Inagawa".[74][75]

- ^ Its copyright was renewed in 1989 by the now-defunct Lorimar-Telepictures.[106] The current copyright holder of the film is not publicly disclosed. Researcher Michihiro Amano states that Toho does not own the rights, and while Warner Bros. was previously considered a possible holder, Paramount Pictures may also be the copyright owner.[59]

References

Citations

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Suzuki, Noriko (2018). "アメリカと日本の架け橋に ―パール・バック『大津波』と戦後冷戦期日米文化関係―" [As bridge between the US and Japan ―Pearl S. Buck’s The Big Wave and the US-Japan cultural relationship in the Cold War era―] (PDF). J-STAGE (in Japanese). International Journal of Cultural Studies. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c Buck 1962, p. 245.

- ^ "The Big Wave (1962)". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c Pressbook 1962, p. 1.

- ^ a b c Sherk 1992, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e Harris 1970, p. 304.

- ^ a b c Hischak 2012, p. 25.

- ^ Hischak 2012, p. 24.

- ^ Conn 1996, p. 342.

- ^ a b c Suzuki, Noriko (2015). "「幻の映画」をめぐって : 『大津波』日米合同映画製作とパール・バック" [Considering the "Rare Picture" : The US-Japan Film Making of The Big Wave and Pearl Buck] (PDF). Retrieved June 7, 2025.

- ^ Harris 1970, p. 305.

- ^ a b Stirling 1983, p. 256.

- ^ a b c Thomas 1960, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "The Big Wave (1962)". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved March 23, 2025.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 101.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 11.

- ^ Motion Picture Exhibitor 1960, p. 9.

- ^ The Leaf-Chronicle 1960, p. 4.

- ^ Takeuchi & Yamamoto 2001, p. 335.

- ^ Archer 1961, p. 35.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 13.

- ^ a b c d e Falk 1961, p. 425.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 34.

- ^ a b Buck 1962, p. 165.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 36.

- ^ Los Angeles Times 1960, p. 79.

- ^ a b c Variety 1960a, p. 19.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 168.

- ^ a b c Variety 1960b, p. 5

- ^ a b Buck 1962, p. 54.

- ^ a b Buck 1962, p. 247.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 98.

- ^ a b Buck 1962, p. 112.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 123.

- ^ Sherk 1992, p. 163.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 118.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 120.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 121.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 124.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 125.

- ^ The Japan Times 1960, p. 3.

- ^ Variety 1960c, p. 21.

- ^ Los Angeles Mirror 1960, p. 20.

- ^ Battle Creek Enquirer 1960, p. 11.

- ^ a b c "「雲仙市」で幻の映画の上映実現を目指す" [Aiming to Screen an Elusive Film in Unzen City]. Nagasaki Shimbun. August 18, 2005. Archived from the original on October 25, 2005. Retrieved August 11, 2025.

- ^ Jarrard 1960, p. 26.

- ^ a b c "ゴジラの円谷監督が特撮担当、幻の映画を"初上映"" [Director Tsuburaya of Godzilla is in charge of special effects, "premiere" of the fantasy movie]. ZAKZAK (in Japanese). October 24, 2005. Archived from the original on October 28, 2005. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 175.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 209.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Big Wave --- An Unusual 2nd Feature". Variety. September 26, 1962. p. 19.

- ^ Bock, Audie (1978). Japanese Film Directors. Japan Society. pp. 185–186. ISBN 0-87011-304-6.

- ^ "Claims Shooting in Japan for Yanks Without Major Problem If Done Right". Variety. October 25, 1961. p. 18.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 186.

- ^ Stirling, Nora B. (1983). Pearl Buck: A Woman in Conflict. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-8329-0261-1.

- ^ a b c Conn 1996, p. 345.

- ^ a b Parsons, Louella (September 30, 1960). "On The Sets". The Houston Chronicle. p. 23 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Johnson, Erskine (October 22, 1960). "In Hollywood". Courier News. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "A Bridge for Passing". Kirkus Reviews. Retrieved August 5, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Amano, Michihiro (March 12, 2017). "雲仙・普賢岳噴火による津波被害を題材にした幻の日米合作映画『大津波』の内容と撮影風景を天野ミチヒロが語る" [Michihiro Amano discusses the content and filming of the elusive American-Japanese co-production The Big Wave, which is based on the tsunami damage caused by the eruption of Mount Unzen]. TOCANA (in Japanese). p. 2. Retrieved August 12, 2025.

- ^ a b "How Sessue Saved Girl From Shark". Windsor Star. October 15, 1960. p. 19 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 243.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 244.

- ^ a b Buck 1962, p. 164.

- ^ a b c Buck 1962, p. 187.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 206.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 199.

- ^ a b La Farge 1988, p. 95.

- ^ Buck 1962, pp. 238–239.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 250.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 251.

- ^ a b Buck 1962, p. 252.

- ^ Buck, Pearl S. (November 20, 1960). "A Thank You Note". The Japan Times. p. 8.

- ^ a b c "「災害映画」の変容-現代社会におけるエンターテイメント性の研究-" [The transformation of "disaster movies" - A study of entertainment value in modern society] (PDF) (in Japanese). 2016.

- ^ a b Krafsur, Richard P (1976). The American Film Institute Catalog: Feature Films, 1961-70. R.R. Bowker. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-8352-0440-8.

- ^ a b Galbraith IV, Stuart (1996). The Japanese Filmography: 1900 through 1994. McFarland & Company. pp. 118–119. ISBN 0-7864-0032-3.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 241.

- ^ Buck 1962, p. 156.

- ^ a b Buck 1962, p. 159.

- ^ "黛敏郎作品リスト" [List of works by Toshiro Mayuzumi] (in Japanese). So-net. Archived from the original on June 4, 2016. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ a b c The 1963 Film Daily Year Book of Motion Pictures. Wid's Films and Film Folk, Inc. 1963. p. 187.

- ^ a b c Buck 1962, p. 160.

- ^ "Disney Finds Gain In Native Voices". Variety. Tokyo. May 31, 1961. p. 13.

- ^ Larsen, Penny (December 28, 1960). "New Hope, Pa". Variety. p. 54.

- ^ Harris 1970, pp. 305–306.

- ^ a b "Ratings of Current Motion Pictures". Consumer Bulletin. Vol. 44, no. 5. May 1961. p. 35.

- ^ "Many Are Family Pictures; Nine More Releases Than for April '61". Boxoffice. April 9, 1962. p. 4 – via Yumpu.

- ^ a b Boxoffice Barometer: Review 62/63 Preview. Boxoffice. 1963.

- ^ Zimmer 2017, p. 223.

- ^ "'Bridge' at Met". The Boston Globe. May 16, 1962. p. 10 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Guild: Two Features". Zavala County Sentinel. La Pryor, Texas. October 5, 1962. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Show Dates: Park". Abilene Reporter-News. June 10, 1962. p. 19 – via Newspaper.com.

- ^ "Movie Houses Announce 10 Showings". The Ithaca Journal. August 11, 1962. p. 5 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Screen Time". The Republican. May 15, 1963. p. 36 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "At Cascades Sunday". The Herald-Times. May 18, 1963. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Sellersville Glitters As Pearl S. Buck Attends Premiere Of Her Film Last Night". News–Herald. Perkasie, Pennsylvania. October 18, 1962. p. 1.

- ^ Marcovitz, Hal (March 20, 2001). "Pearl Buck's son speaks of her love ** In Bucks library, he recalls happy childhood at Green Hills Farm". The Morning Call. Archived from the original on July 24, 2023. Retrieved July 19, 2025.

- ^ Amador, María Luisa; Blanco, Jorge Ayala (1986). Cartelera Cinematográfica, 1960-1969 [Movie Listings, 1960-1969] (in Spanish). Centro Universitario de Estudios Cinematográficos, Coordinación General de Difusión Cultural, Dirección de Literatura/UNAM. p. 151. ISBN 978-968-837-945-5 – via Google Books.

1454. Tifón en Japón (The Big Wave). Norteamericano-japonesa. Dir. Tad Danielewski. Int. Sessue Hayakawa, Koji Shitara Hiroyuki Ota. Prod. Toho y Stratton, Allied Artists, 1961. Cine París, febrero 12 de 1963

- ^ La Farge 1988, p. 97.

- ^ Sherk 1992, p. 165.

- ^ "Heat Wilts Hub Albeit 'Honey' Hotsy $15,000; 'Fear' Fine 14G; 'Bird' 13G". Variety. May 23, 1962. p. 8.

- ^ "'Man' Big $29,000 for 2 Det. Spots; 'Lolita' Wow 18½G, 'Music' Torrid $20,000; 'Mink' Sockeroo 18G, 5th". Variety. July 25, 1962. p. 10.

- ^ "'Interns' Nifty $12,000, Buff; 'Man' Slight 8G". Variety. August 22, 1962. p. 16.

- ^ 'Sky' High $12,500, Frisco; 'Polo' 13G. Variety. September 5, 1962. p. 9.

- ^ "First Run on TV: The Big Wave". The Fresno Bee. September 21, 1963. p. 9. Retrieved July 19, 2025.

- ^ "Sunday, March 20". The St. Tammany News-Banner. Covington, Louisiana. March 14, 1977. p. 18. Retrieved July 19, 2025.

- ^ "The Big Wave. By Allied Artists Pictures Corporation". publicrecords.copyright.gov. United States Copyright Office. Retrieved July 14, 2025.

- ^ "Review Digest". Boxoffice. June 25, 1962. p. 13.

- ^ a b c "The Big Wave". Mediafilm. Retrieved July 7, 2025.

- ^ a b c d "Reviews". Motion Picture Exhibitor. April 18, 1962.

- ^ a b "Opinions on Current Productions: The Big Wave". Boxoffice. June 18, 1962. p. 11. Retrieved July 14, 2025 – via Yumpu.

- ^ Scheuer, Steven H. (1977). Movies on TV. Bantam Books. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-553-11451-5.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (1980). TV Movies. p. 56.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2015). Turner Classic Movies Presents Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide: From the Silent Era Through 1965 (3rd ed.). Penguin. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-698-19729-9.

- ^ Blockbuster Entertainment (September 1996). Blockbuster Entertainment Guide to Movies and Videos 1997. Dell Publishing. p. 109. ISBN 0-440-22275-3.

- ^ Buck 1962, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Galbraith IV 1996, p. 51.

- ^ Ackerberg, Erica (November 10, 2022). "Lit Trivia: Do You Know These Classic Screen Adaptations of Popular Books?". The New York Times. Retrieved August 10, 2025.

Works cited

- Allied Artists (1962). The Big Wave (pressbook).

- Archer, Eugene (July 12, 1961). "5 ON STAGE TOUR TO WORK ON FILM; Members of New York Group Also to Do Sartre's 'No Exit'". The New York Times. p. 35. Retrieved July 9, 2025.

- Harris, Theodore Findley (March 1970). Pearl S. Buck: A Biography. Methuen Publishing. ISBN 0-416-15920-6.

- Hischak, Thomas S. (2012). Literature on Stage and Screen: 525 Works and Their Adaptations. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0-7864-6842-3.

- Buck, Pearl S. (April 2, 1962). A Bridge for Passing. John Day Company.. Republished 2013 as ISBN 9781480421240.

- Conn, Peter (1996). Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-56080-2.

- Takeuchi, Hiroshi; Yamamoto, Shingo, eds. (May 7, 2001). 円谷英二の映像世界 [Eiji Tsuburaya's Visual World] (in Japanese) (2nd ed.). Jitsugyo no Nihon Sha (published July 11, 2001). ISBN 4-408-39474-2.

- "Pearl Buck Film Begins". Los Angeles Mirror. Los Angeles. September 17, 1960. p. 20. Retrieved March 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Clavell Assigns Self to 'Unwanted'". Los Angeles Times. August 8, 1960. p. 79 – via Newspapers.com.

- Thomas, Bob (December 28, 1960). "Pearl Buck To Make Movie Based on The Big Wave". The Gettysburg Times. p. 3.

- "Has Top Role". Battle Creek Enquirer. Battle Creek, Michigan. November 25, 1960. p. 11. Retrieved March 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- Jarrard, Jack E. (December 16, 1960). "Utahn Produces Film In Far East". Deseret News. Salt Lake City, Utah. p. 26. Retrieved March 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Pearl Buck In Tokyo For Film". The Leaf-Chronicle. Clarksville, Tennessee. May 4, 1960. p. 4. Retrieved April 3, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- Sherk, Warren (1992). Pearl S. Buck: Good Earth Mother. Drift Creek Press. ISBN 978-0-9626441-3-9.

- "Transition To Big Pic Policy Nearing Completion, Says Broidy". Motion Picture Exhibitor. May 11, 1960. p. 9.

- Falk, Ray (January 15, 1961). "JAPAN'S OPEN-DOOR PICTURE POLICY". The New York Times. Retrieved July 9, 2025.

- Zimmer, Daniel (2017). Reynold Brown: A Life in Pictures (2nd ed.). The Illustrated Press. p. 223. ISBN 978-0-9970292-7-7.

- "'Wave' Won't Bare Girl Divers in U.S. Version". Variety. September 28, 1960. p. 19.

- "Last-Minute Change of Femme for Big Wave". Variety. October 5, 1960. p. 5.

- "Friday". The Japan Times. September 9, 1960. p. 3.

- "Hollywood Productions Pulse: Allied Artists". Variety. November 9, 1960. p. 21.

- La Farge, Ann (1988). Pearl Buck. ISBN 978-1-55546-645-9.

External links

- The Big Wave at IMDb