Taschereau Court (1902–1906)

| Taschereau Court | |

|---|---|

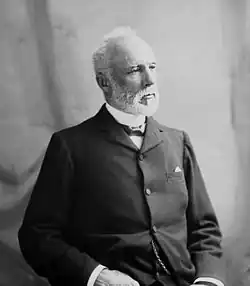

Henri Elzéar Taschereau in 1898. | |

| November 21, 1902 – May 1, 1906 (3 years, 161 days) | |

| Seat | Second Supreme Court of Canada building |

| No. of positions | 6 |

The Taschereau Court was the period in the history of the Supreme Court of Canada from 1902 to 1906, during which Henri Elzéar Taschereau served as Chief Justice of Canada. Taschereau succeeded Samuel Henry Strong as Chief Justice after the latter's resignation, and held the position until his resignation on May 1, 1906.

Like all iterations of the Supreme Court prior to 1949, the Taschereau Court was largely overshadowed by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which served as the highest court of appeal in Canada. Decisions of the Privy Council on Canadian appeals were binding on all Canadian courts.

The Taschereau Court is notable for the considerable turnover of justices during its brief existence. Justices David Mills and John Douglas Armour died shortly after their appointments, and justices Wallace Nesbitt and Albert Clements Killam both resigned from the after a short period of service. Additionally, the Taschereau Court continued to face many of the same criticisms as its predecessors, the Ritchie Court and Strong Court, including the concerns about the conduct of its justices, the political nature of judicial appointments, the excessive length and lack of clarity in its decisions, and significant delays in the publication of those decisions.

Membership

The Supreme Court Act, 1875 established the Supreme Court of Canada, composed of six justices, two of whom were allocated to Quebec under law, in recognition of the province's unique civil law system.[1][2][ps 1] Early appointments to the Court reflected an unwritten regional balance, with two justices from Ontario and two from the Maritimes.[3][4] There was no representation from the western territories or British Columbia.[5]

On November 17, 1902, Chief Justice Samuel Henry Strong resigned from the Court after Justice Minister Charles Fitzpatrick arranged for Strong to receive both his judicial pension and a salary as chair of a commission to revise and consolidate the statutes of Canada.[6][7] Justice Henri Elzéar Taschereau, the most senior puisne justice, was elevated to Chief Justice, following the established tradition.[8] Taschereau became the first Quebec justice to hold the position of chief justice.[9] Snell and Vaughn note that Taschereau was viewed by the legal community as the most qualified justice on the Court at the time, and that his appointment helped legitimize the Supreme Court in the eyes of Quebec.[9]

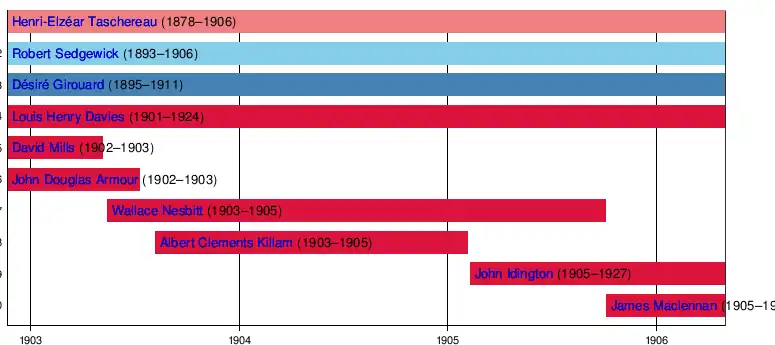

Justices from the Strong Court who continued into the Taschereau Court included Robert Sedgewick, Désiré Girouard, Louis Henry Davies, David Mills.

With the elevation of Taschereau to the role of Chief Justice, John Douglas Armour was appointed to fill the vacant Ontario seat from Chief Justice Strong's resignation. At the time, Armour was Chief Justice of Ontario and had served 24 years as a judge, but he was already in poor health.[10] Armour served on the Supreme Court for only 232 days, participating in two sessions, before dying in England while serving on the Alaska Boundary Commission.[9][11]

Following the death of David Mills on May 8, 1903, Wallace Nesbitt was appointed to the Court on May 16. A prominent lawyer from Toronto and Hamilton, Nesbitt was considered a strong choice, with a solid professional reputation and a relatively young age of 45.[9][11] His appointment was unusual in the era of partisan appointments by the Liberal Laurier government, as he was a Conservative.[9][12] Nesbitt had particular expertise in corporate and commercial law, with significant experience in insurance law.[12]

On July 11, 1903, Armour died after only seven months after his appointment, and was replaced with Albert Clements Killam, the Chief Justice of Manitoba and first Western appointment to the Supreme Court of Canada.[13] Prior to Killam's appointment, there had been considerable pressure from western bar associations and members of Parliament for regional representation on the Court.[13] Killam had practiced law for eight years, briefly served as a Conservative member of the Manitoba Legislature, and was appointed to the Court of Queen's Bench of Manitoba in 1885.[13] Like Nesbitt, he was a relatively young appointee at the age of 53.[13]

Killam's tenure on the Supreme Court was brief. On February 6, 1905, Killam resigned to become Chief Commissioner of the Board of Railway Commissioners.[14] He was replaced on February 10 by John Idington, who came from the High Court of Justice of Ontario.[15] Idington had served as a Crown attorney and had experience in criminal and municipal law, though he had only been on the Ontario bench for a year before his appointment to the Supreme Court.[15] His appointment, which replaced the Court's only western representative with another justice from Ontario, surprised the legal community and western Canada, and prompted speculation that it was difficult to persuade judges to accept an appointment to the Supreme Court.[15][16]

On October 4, 1905, Wallace Nesbitt resigned from the Court, citing "reasons purely private", marking one of the few early resignations in the Court's history.[15] Snell and Vaughan note that Nesbitt appeared to be in good health and that the position on the Court likely did not align with his personal or professional aspirations.[15] He was replaced the following day by James Maclennan, a judge from the Court of Appeal for Ontario. Maclennan had expertise in law of Equity, had previously partnered with former Ontario Premier Oliver Mowat, and joined the bench in 1888 after multiple unsuccessful attempts at elected office.[17] He was described as possessing "common sense," high personal character, and a strong interest in art and literature.[18]

The Taschereau Court concluded with Chief Justice Henri-Elzéar Taschereau's resignation on May 2, 1906, at the age of 69.[17] He publicly stated that his resignation was a condition of his 1904 appointment to the Imperial Privy Council, which entitled him to sit on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.[17] Although Taschereau remained Chief Justice after 1904 until the Laurier government named a successor,[17] he had been on extended sick leave for some time.[18] At the time of his retirement, Taschereau had served 44 years as a judge, including over 27 years on the Supreme Court. In his final years on the bench, his health and energy had noticeably declined.[17]

Timeline

Other branches of government

The Taschereau Court began during the 9th Canadian Parliament, under a majority government led by Liberal Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier.

The Taschereau Court overlapped with one general election, in 1904, which resulted in the Liberal party being re-elected to a majority government.

Relationship with the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council

From 1867 to 1949, the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council served as the highest court of appeal in Canada, and its decisions on Canadian appeals were binding on all Canadian courts. Following the creation of the Supreme Court of Canada, it remained possible—if both parties consented—for appeals to proceed directly from a provincial court of appeal to the Judicial Committee, bypassing the Supreme Court entirely, which became a common practice.[19] By 1900, the Privy Council had become dominant in Canadian jurisprudence, often deciding Canadian cases with "little or no restraint or respect" for the decisions of the Canadian courts from which the appeals originated.[20] By the early 20th century, the Privy Council was viewed as a normal part of the Canadian legal system, and its role was no longer limited to exceptional cases—a point the Committee itself emphasized when urging Canadian lawyers to bring forward only cases of significance or importance.[21]

In 1895, the Parliament of the United Kingdom amended the constituting documents of the Judicial Committee to allow the Queen to summon a limited number of justices from the colonies.[22] In 1904, Chief Justice Taschereau was appointed to the Imperial Privy Council which entitled him to sit on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council alongside former Chief Justice Samuel Henry Strong.[17]

Rulings of the Court

The Taschereau Court heard 258 reported cases between 1902 and 1906, averaging 64.5 cases per year. The Taschereau Court era saw the beginning of growth in the number of appeals heard by the Court and a growing efficiency of the Court to handle those appeals.[23]

- Blackburn v McCallum (1903): on restraints on the transfer of property. The majority held that an absolute transfer of property cannot be subject to substantial restraints that are inconsistent with the nature of the interest conveyed. Furthermore, any condition prohibiting the transferee from incurring debt on the property is void as contrary to public policy.[24][ps 2]

- Gosselin v The King (1903): on Spousal privilege. In a 3–2 majority, the Court upheld a murder conviction and affirmed that a spouse is a competent witness who may be called by the prosecution.[25][ps 3]

- Lake Erie and Detroit River Railway Co v Marsh (1904): describing the role of the Supreme Court. Justice Nesbitt expressed the view that the Supreme Court was established to speak for the country and to develop uniform jurisprudence, particularly with respect to the division of powers under sections 91 and 92 of the Constitution Act, 1867.[26][ps 4]

Administration of the Court

The Court operated with a panel of six judges and required a quorum of four. In cases where the judges were evenly divided (3–3), the appeal was dismissed.[27][28] There was a common practice for each justice to write individual reasons for judgment, rather than issuing joint decisions.[29] This practice, prevalent in the 1880s, continued into the 20th century.[30][31] Combined with the frequent dismissal of appeals due to tied votes, it became difficult to establish clear legal precedents or to determine whether the Court followed a coordinated judicial approach. As a result, the Court primarily resolved disputes by applying existing legal principles, rather than by setting new legal standards.[32] Under the Supreme Court Act, the Court held three sessions per year.[33]

In its early years, the Court did not sit at a traditional shared bench. Instead, each of the six justices had individual desks. Historians Snell and Vaughan note that this setup coincided with a period in the 1880s marked by deep divisions within the Court and a lack of "consultation and cooperation" among the justices.[34] Judicial conferences were introduced in the 1890s, and there is evidence that some justices circulated draft judgments for discussion and engaged in private deliberations.[35] Nevertheless, the resulting decisions often gave the impression that there was little communication among the judges.[35]

The Court recognized the right of applicants from Quebec to use either English or French. While French-language materials were accepted, they were translated into English at the Court's expense.[36] The Supreme Court Act required the Court to publish its own decisions rather than relying on private law reporters, an innovation not found elsewhere in the British Empire. This self-publishing model was intended to ensure that decisions would quickly reach legal professionals and lower court judges.[37] Judgments published in the Supreme Court Reports were printed in the language in which they were delivered and were not translated.[36] The Supreme Court Reports was criticized in its early years for shortcomings, including errors, inconsistent editing and citations, a lack of uniform style, poorly written headnotes, and delays from decision to date of publication.[38] Although improvements were made over time, many of these issues persisted into the 1900s. In 1905, the Court addressed the printing problems by transferring publication responsibilities to a private firm.[39] Despite this change, the early period of the Court was marked by a lack of leadership and consistent standards in case reporting.[40]

Growing political role of the Court

The Laurier government's appointments to the Supreme Court, with some exceptions, were highly partisan.[41] As a result, during the early 20th century, the Court and its justices became increasingly entangled in national politics, both through appointments to government bodies and the growing use of reference questions.[41] These reference questions became increasingly more political in nature, exposing the Court to criticism and attack from the Conservative opposition.[41]

As Chief Justice, Taschereau publicly criticized the British press for its coverage of Lord Dundonald, accusing it of conservative bias and calling for Dundonald's recall by the Imperial government.[42] At the time, Taschereau was in London serving on the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Within two days of his statement, the Laurier government recalled him to Canada.[43]

Changes to the structure and jurisdiction of the Court

Beginning in 1902, Edward Robert Cameron, Registrar of the Supreme Court, participated in efforts to revise the Supreme Court Act. He sought the approval of Minister of Justice Charles Fitzpatrick to conduct a comprehensive review of the statute and to address anomalies in the Court's jurisdiction. Between 1893 and 1903, there was a significant increase in motions to quash for lack of jurisdiction, with more than 50 such motions successfully granted during that period. Although Cameron ultimately recommended the enactment of a new statute, the proposed changes were instead incorporated into the general revision of federal statutes approved in 1906.[44]

Improving inter-personal relationships and administration of the Court

Snell and Vaughan note that the retirement of Chief Justice Samuel Henry Strong led to an improvement in the interpersonal dynamics of the Court. Several justices made efforts to foster a more cooperative atmosphere.[45]

Despite these improvements, the Taschereau Court continued to struggle with drafting and publishing decisions. In The King v Stewart, a 3–1 majority dismissed both the appeal and the cross-appeal, but no written reasons were provided by the majority. In contrast, Chief Justice Taschereau issued a detailed dissent, which was published in the Supreme Court Reports.[40][ps 5]

Costs and salaries of the Court

Judicial salaries became a public issue in the 1890s, as the government realized it needed to provide justices with alternative income sources in order to retire. Justice John Wellington Gwynne delayed retirement and served until his death in office at the age of 87.[6] In 1897, Justice Taschereau requested increased compensation due to the additional responsibilities he assumed during Chief Justice Strong’s frequent medical absences.[46] Strong himself only retired after securing both his judicial pension and a salaried position as chair of a commission to revise and consolidate the statutes of Canada.[6]

Concerns over judicial compensation were longstanding. During the 1880s, Supreme Court justices received an annual salary of $7,000 (equivalent to $230,111 in 2023), with the Chief Justice receiving an additional $1,000. Even at the time, this was considered low, and rumours circulated that all the justices, except for Chief Justice Ritchie, had taken several months' salary in advance as loans from banks.[47] In the 1890s, Supreme Court justices were the third lowest paid in the British Empire, ahead of only Tasmania and Natal. The Colony of Victoria offered judicial salaries nearly twice that of Canada's Supreme Court.[6] Pensions were also inadequate, providing little retirement security and no benefits for widows.[48] In 1903, judicial pensions were improved to provide lifetime support for justices, and in 1906, salaries were increased to $9,000 (equivalent to $288,433 in 2023), with an additional $1,000 for the Chief Justice.[49]

The cost of operating the Supreme Court steadily increased: from $54,530 in 1880 (equivalent to $1,792,564 in 2023), to $60,840 in 1890 (equivalent to $2,208,249 in 2023), and $66,087 in 1900 (equivalent to $2,542,306 in 2023).[48] These rising expenses regularly drew criticism from the opposition. Justice Minister and future Supreme Court Justice David Mills remarked that "maintaining [the Court] costs altogether too much for what it does."[48]

Expansion of duties of justices

In the late 1890s, Supreme Court justices increasingly took on additional roles at the request of the federal government, reflecting both the Court's evolving stature and its growing involvement in public affairs beyond the bench. These political and quasi-judicial appointments signaled a gradual increase in respect for the Court.[22] However, they also reinforced the perception that the Court was not fully independent from the government and could be used as a political instrument.[43] In 1903, for example, Justice Armour was appointed to serve on the Alaska Boundary Committee.[43]

Appraisal

Historian Ian Bushnell describes the Supreme Court during the period from 1903 to 1929—including the Taschereau, Fitzpatrick, Davies, and Anglin Courts—as "the sterile years."[50]

Criticism of the Court during this time focused heavily on the politically motivated nature of many judicial appointments.[51] While some legal journals occasionally defended the Court against criticism in the press, Bushnell observes that such defences were often driven more by a desire to preserve the credibility of the legal system as a whole than by genuine support for the Supreme Court itself.[52] By 1902, only two of the six justices had prior judicial experience, and the Canadian Law Times remarked that the Court's composition was held in the lowest regard in its history.[51]

Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier appointed ten justices during his tenure, giving him a significant opportunity to shape the Court. However, there was no consistent approach to appointments.[53] Selections reflected a mix of merit, patronage, and political interest, rather than a clear vision for strengthening the Court or developing its institutional role.[53] Additionally, the Laurier government's decision to appoint Justice Albert Clements Killam to the Board of Railway Commissioners shortly after his elevation to the Supreme Court was seen as damaging to the Court's stature. Snell and Vaughan note that this move underscored the perception of the Court, in its early period, as "a political body subject to the partisan political maneuverings of the government."[14]

See also

- Supreme Court of Canada cases

- List of Supreme Court of Canada cases (Richards Court through Fauteux Court)

- List of Canadian appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, 1900–1909

References

- ^ Bushnell 1992, p. 15.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 12.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 27.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, pp. 12–15.

- ^ a b c d Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 65.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, p. 165.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 85.

- ^ a b c d e Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 86.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Bushnell 1992, p. 179.

- ^ a b Bushnell 1992, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 87.

- ^ a b Snell & Vaughan 1985, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b c d e Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 88.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, p. 181.

- ^ a b c d e f Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 89.

- ^ a b Bushnell 1992, p. 182.

- ^ McCormick 2000, p. 2.

- ^ Macklem, Patrick; Mathen, Carissima, eds. (2022). Canadian Constitutional Law (Sixth ed.). Toronto: Emond Montgomery Publications Limited. p. 74. ISBN 978-1-77462-137-0.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, p. 169.

- ^ a b Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 68.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 100.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, pp. 171–175.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, pp. 175–179.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 114.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 67.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, p. 77.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, p. 155.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, pp. 77, 119.

- ^ Laskin, Bora (1975). "The Supreme Court of Canada: The First One Hundred Years a Capsule Institutional History". Canadian Bar Review. 53 (3): 466. 1975 CanLIIDocs 19.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 40.

- ^ a b Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 76.

- ^ a b Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 21.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 36, 73.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 110.

- ^ a b Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 111.

- ^ a b c Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 93.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 96.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 106–107.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, pp. 100–101.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 64.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 45.

- ^ a b c Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 66.

- ^ Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 112.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, p. viii.

- ^ a b Bushnell 1992, p. 164.

- ^ Bushnell 1992, p. 161.

- ^ a b Snell & Vaughan 1985, p. 82.

Primary sources

- ^ The Supreme and Exchequer Court Act, S.C. 1875, c. 11 (The Supreme and Exchequer Court Act at Canadiana)

- ^ Blackburn v McCallum, 1903 CanLII 68, (1903) 33 SCR 65, Supreme Court (Canada)

- ^ Gosselin v The King, 1903 CanLII 42, (1903) 33 SCR 255, Supreme Court (Canada)

- ^ Lake Erie and Detroit River Rway Co v Marsh, 1904 CanLII 9, (1904) 35 SCR 197, Supreme Court (Canada)

- ^ The King v Stewart, 1902 CanLII 79, (1902) 32 SCR 483, Supreme Court (Canada)

Further reading

Works centering on the history of the Supreme Court of Canada

- Adams, George W.; Cavalluzzo, Paul J. (1969). "The Supreme Court of Canada: A Biographical Study". Osgoode Hall Law Journal. 7 (1): 61–86. doi:10.60082/2817-5069.2358. 1969 CanLIIDocs 331.

- Bushnell, Ian (1992). Captive Court: A Study of the Supreme Court of Canada. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0851-4.

- McCormick, Peter (2000), Supreme at last: the evolution of the Supreme Court of Canada, J. Lorimer, ISBN 978-1-55028-693-9

- Snell, James G.; Vaughan, Frederick (1985). The Supreme Court of Canada: History of the Institution. Toronto: The Osgoode Society. ISBN 978-0-8020-3417-5.

Works centering on the Taschereau Court Justices

- Howes, David (1998). "Taschereau, Sir Henri-Elzéar". In Cook, Ramsay; Hamelin, Jean (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XIV (1911–1920) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Girard, Philip (1994). "Sedgewick, Robert". In Cook, Ramsay; Hamelin, Jean (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XIII (1901–1910) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Smith, Michael Lawrence (1998). "Girouard, Désiré". In Cook, Ramsay; Hamelin, Jean (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XIV (1911–1920) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Bumsted, J. M. (2005). "Davies, Sir Louis Henry". In Cook, Ramsay; Bélanger, Réal (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XV (1921–1930) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Vipond, Robert C. (1994). "Mills, David". In Cook, Ramsay; Hamelin, Jean (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XIII (1901–1910) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Kyer, C. Ian (2005). "Nesbitt, Wallace". In Cook, Ramsay; Bélanger, Réal (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XV (1921–1930) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Gibson, Lee (1994). "Killam, Albert Clements". In Cook, Ramsay; Hamelin, Jean (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XIII (1901–1910) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

- Bale, Gordon (2005). "Idington, John". In Cook, Ramsay; Bélanger, Réal (eds.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. XV (1921–1930) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press.

Other relevant works

- Snell, James G. (1980). "Frank Anglin Joins the Bench: A Study of Judicial Patronage, 1897-1904". Osgoode Hall Law Journal. 18 (4): 664–673. doi:10.60082/2817-5069.2035.