Tabula Siarensis

_Portrait_de_Germanicus_-_Mus%C3%A9e_Saint-Raymond_Ra_342_c.jpg)

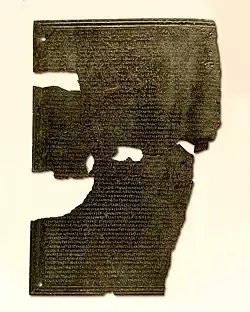

The Tabula Siarensis (English: "Table from Siarum") is the modern name for a Roman inscription written in 19/20 AD and discovered in southern Spain in the early 1980s. The tablet contains a comprehensive resolution by the Roman Senate regulating the honors to be bestowed upon the death of the general Germanicus. The inscription on the bronze plate, found in two fragments, is considered an important epigraphic source on the early Roman Empire. The text sheds light on the complex relationship between Emperor Tiberius and Germanicus, on Rome's renunciation of the conquest of Germania after 16 AD, and on the working methods of Tacitus, who also reports on the honors paid to the deceased. The plate is now displayed at the Museo Arqueológico Provincial de Sevilla under inventory number DJ1986/29-01.[1]

Find

The Tabula Siarensis was discovered near the southern Spanish village of La Cañada (ancient name Siarum), near Utrera/Seville. It consists of two fragments of a bronze inscription tablet depicting a Senate decree and a draft law, written primarily on December 19 AD, concerning the extensive honors to be bestowed on the anniversary of the death of Germanicus (who died on 10 October 19 AD), the nephew and adopted son of Emperor Tiberius.[2]

The year 1982 is generally considered the year of the Tabula Siarensis's discovery, although this is uncertain. The authoritative first description by Julián González, published in 1984, mentions spring 1982, but the author had already referred to the find in 1980.[2]

Contents

Structure

The Tabula Siarensis comprises two parts: the main part is a detailed Senate resolution dated 16 December 19 AD on the honors bestowed upon the deceased, written on the first fragment and the first two columns of the second fragment. The third column contains fragments of a bill, likely introduced in 20 AD as the Lex Valeria Aurelia. The texts are incomplete, and some parts have been reconstructed.[3]

Fragment I (Senate resolution)

- Lines 1–8: Introduction; participation of the Senate, Tiberius, and the imperial family in the honors.

- Lines 9–21: Provisions for the construction of a triumphal arch (Ehrenbogen) in the Circus Flaminius and a commemorative plaque to be affixed there.

- Lines 9–12: Details on the construction of the triumphal arch in the Circus Flaminius: made of marble, decorated with the standards of the Germanic tribes defeated by Germanicus.

- Lines 12–15: Germanicus's achievements in Germania to be recorded on a commemorative plaque: victory over tribes, securing Gaul, recovery of the military standards (implied, but not mentioned: two of the three legion eagles lost in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD), revenge for the defeat caused by treachery (of Varus), and settlement of relations in Gaul.

- Lines 15–17: Achievements in the East: organization of provinces and kingdoms on behalf of Tiberius, installation of a king in Armenia.

- Lines 17–18: Death of Germanicus before he could hold a (small) triumph in Rome, which had been approved by the Senate.

- Lines 18–21: Provisions for the design of the statues on the archway: Germanicus in a triumphal chariot, accompanied by his father Drusus, his mother Antonia, his wife Agrippina, his sister Livilla, his brother Claudius, his uncle Tiberius, and his sons and daughters.

- Lines 23–25: Construction of a second archway with a statue and inscription on a pass in the Amanus Mountains in Syria.

- Lines 26–29: Construction of a third archway over the Rhine near the Drusus Catafalque in Mainz, depicting Germanicus receiving the captured standards (of the Varus legions) from the Germanic tribes.

- Lines 29–34: Instructions for the Gauls and Germanic tribes east of the Rhine to make sacrifices at the cenotaph of Drusus on the anniversary of Germanicus's death; parade march of the stationed legions through the arch on the anniversary of his death.

- Lines 35–37: Erection of further memorials to Germanicus (e.g., in the forum of Antioch, where Germanicus's body was burned).[4]

Fragment II, first column (continuation of Senate resolution)

- Lines 1–5: Sacred rules.

- Lines 6–11: Secular regulations and prohibitions for the holiday (e.g., hospitality, celebrations, games).

- Lines 11–14: Provisions for postponing the games in honor of Augustus (ludi Augustales scaenici, from 5 to 11 October) to avoid conflicts with the anniversary of Germanicus's death.[4]

Fragment II, second column (final provisions of the Senate resolution)

- Lines 1–19: Honors bestowed by knighthood and the people (upper part difficult to reconstruct).

- Lines 20–26: Publication regulations; bronze tablets to be placed in various locations throughout the empire.

- Lines 26–33: Order to the designated consuls (of the year 20 AD) to introduce a corresponding law to honor the memory of Germanicus.[4]

Fragment II, third column (legislative proposal)

- Legislative proposal with detailed provisions on commemoration and honoring the deceased.[4]

Parallel tradition

Some of the contents of the Tabula Siarensis have been preserved in other inscriptions and ancient historical writings. In the early 19th century, three fragments of a tablet containing honours bestowed on Germanicus were discovered in Rome. In 1947, the Tabula Hebana was found. The fragments of this bronze tablet contain the law for the honors bestowed on Germanicus, the draft of which is listed on the Tabula Siarensis, Fragment II, column 3.[5]

The provisions are recorded in Tacitus's Annals, which accurately reports the contents of the Senate's decision.[5]

Historical background

Germanicus (born 24 May 15 BC; died 10 October 19 AD in Antioch on the Orontes) was a Roman general known for his campaigns in Germania. He was the son of the general Drusus and the nephew and adopted son of Tiberius.[6]

The relationship between the charismatic Germanicus and his unpopular uncle Tiberius, who had been emperor since 14 AD as the successor to Augustus, was tense. At the beginning of Tiberius's reign, a revolt by the legions in Germania occurred; the troops sought to overthrow Tiberius and enthrone Germanicus. Although Germanicus remained loyal, Tiberius had reason to fear a rival, especially since the elderly Augustus had designated Germanicus as Tiberius's successor. Tiberius halted Germanicus's campaigns in Germania in 16 AD, despite Germanicus's fierce resistance, but granted him a triumphal procession through Rome in 17 AD. Germanicus was then sent to the eastern part of the empire with a government mandate. However, his work there again gave Tiberius cause for complaint. In 19 AD, Germanicus died unexpectedly, presumably poisoned by his political opponent Piso; there is no evidence that Tiberius was involved in the murder.[6]

Tiberius exploited the widespread mourning for Germanicus to further his own interests. The decisions bore the hallmarks of Tiberius, for example, in the reinterpretation of the war aims in Germania (Fragment I, lines 12–15). The subjugation of the Germanic tribes as far as the Elbe, as Augustus had envisioned and Germanicus had sought to achieve, was no longer the goal; instead, limited protection and revenge objectives were declared binding and achieved. The political message of the Tabula Siarensis thus contrasts with the successes celebrated during the triumphal procession in 17 AD. While the defeat of the tribes as far as the Elbe was celebrated, and the Cherusci, Chatti, and Angrivarii were mentioned by name, the Tabula Siarensis only briefly mentions the achievements; no tribe, battle site, or Elbe destination is named. According to Boris Dreyer, the tributes to Germanicus played a decisive role in the public enforcement of the new Germanic policy, which had likely been officially communicated since 16 AD. While Germanicus's actual successes were described briefly, the narrative elements went far beyond the usual descriptions of his achievements.[6]

Significance for research

The discovery of the Tabula Siarensis is considered a significant event because it contains not only the (already partially known) law honoring Germanicus but also the underlying Senate decrees. This provides direct insight into Roman policy toward the Germanic tribes after 16 AD, as "with this precious new find, we finally have the long-missing, directly contemporary source evidence that, as an official statement, unambiguously signals the Roman renunciation of the occupation of Germania (which had been effective since 16/17 AD)—at least for the era of Tiberius."[3]

At the same time, the Tabula Siarensis offers a rare opportunity to compare an original Senate decree with Tacitus's version. This provides "access to a better understanding of Tacitus's historiographical working methods." The Tabula Siarensis confirms Tacitus's account of the honors. Other parts of the Annals also contain carefully written reports that were "clearly based on the 'acta senatus'." However, Tacitus weighted elements differently—for example, he summarized the detailed provisions for the erection of triumphal arches in a single sentence.[3]

See also

References

- ^ González Fernández, Julián (1988). González Fernández, Julián (ed.). Estudios sobre la Tabula Siarensis [Studies on the Tabula Siarensis] (in German). Madrid: Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas. ISBN 84-000-6876-9.

- ^ a b Lott, J. Bert (2012). Death and Dynasty in Early Imperial Rome: Key Sources, with Text, Translation, and Commentary (in German). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 209–236. ISBN 978-0-521-67778-3.

- ^ a b c Perné, Walter (2006). De filiis filiabusque Germanici Iulii Caesaris e litteris, testimoniis epigraphicis, nummis demonstrata. Quellensammlung und biographische Auswertung [De filiis filiabusque Germanici Iulii Caesaris e litteris, testimoniis epigraphicis, nummis demonstrata. Source collection and biographical analysis] (PDF) (Doctoral dissertation) (in German). University of Vienna. pp. 63–70.

- ^ a b c d Lebek, Wolfgang Dieter (1986). "Schwierige Stellen der Tabula Siarensis" [Difficult passages in the Tabula Siarensis] (PDF). Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik (in German). 66: 31–48. JSTOR 20186389.

- ^ a b Wiegels, Rainer (2015). "Trauer um Germanicus. Instrumentalisierung einer Totenehrung" [Mourning Germanicus. Instrumentalising a memorial service] (PDF). Varus-Kurier (in German). 17: 1–9.

- ^ a b c Sánchez-Ostiz, Alvaro (1999). Tabula Siarensis: Edición, traducción y comentario [Tabula Siarensis: Edition, translation and commentary] (in German). Pamplona: Ediciones Universidad de Navarra. ISBN 84-313-1665-9.

External links

- Tabula Siarensis illustrations in the Online Collections.