Taş Tepeler

The Taş Tepeler (Turkish, literally 'Stone Mounds') are a group of Neolithic archaeological sites in Upper Mesopotamia (al-Jazira), near the city of Urfa in modern-day Turkey.[1] They are the remains of a number of settlements dating to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period [2] (c. 9500–7000 BC),[3] during transition from nomadic hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities in the region.

Economy and culture

The societies of Taş Tepeler still had not yet developed the herding of animals or agriculture: their subsistence depended on hunting and selective harvesting of wild cereal grasses.[4]

Man's domestication of animals seems to have started within the broad region of the Taş Tepeler culture, and early efforts at animal management, especially symbolic representations and entrapment methods, seem to broadly coincide with the development of Göbekli Tepe, as shown in its animal art.[5] The earliest dates for the actual domestication of animals are c. 9000 BCE for goats and sheep, c. 8500 BCE for pigs, and c. 8000 BCE for cattle, all in the area of Northern Mesopotamia.[5] Çayönü Tepe for example may be where some of the first animal domestication occurred, as the pig may have first been domesticated there in 8,500 BCE.[6]

Sites such as Çayönü Tepe developed from the cultural tradition of Gobekli Tepe, and started to implement agriculture from the 9th millenium BCE, as well as other sites such as Neva Çori or Cafer Höyük, Hallan Çemi, Abu Hureyra and Jerf al Amar.[7]

-

![Origin and dispersal of domestic livestock species in the Fertile Crescent (dates Before Present).[8][9]](./_assets_/Origin_and_dispersal_of_domestic_livestock_species_in_the_Fertile_Crescent_(dates_Before_Present).png)

-

![Man with auroch, holding a contraption and likely controlling the animal. Sayburç, 9th millennium BCE.[10]](./_assets_/Man_with_auroch%252C_holding_a_contraption._Saybur%C3%A7_reliefs%252C_9th_millennium_BCE.jpg)

-

Painted boar from Göbekli Tepe, 8700-8200 BCE

Painted boar from Göbekli Tepe, 8700-8200 BCE

Religion

Many Taş Tepeler sites contain large stone buildings with the T-shaped obelisks characteristic of Göbekli Tepe.[13] They are characterized by their monumentality, which sets them apart from earlier sedentary Pre-Pottery Neolithic archaeological sites such as Körtik Tepe, which is not included in the Taş Tepeler category.

These buildings may been some of the earliest sanctuaries for ancestor cult.[4] They were furnished with T-shaped stelae, such as those of Gobekli Tepe, Karahan Tepe, or the rectangular stelae of Çayönü Tepe.[4] These stelae are thought to have been symbolic images of men or gods. Several stelae had anthropomorphic reliefs, or even human heads, carved on them.[4] These findings suggest stela worship, a form of cult which was prevalent in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, and remained widespread in the Near-East until the 1st millennium BC.[4]

T-shaped stelae

The T-shaped pillar tradition seen at Göbekli Tepe is unique to the Urfa region but is found at most PPN sites.[14] These include Nevalı Çori, Hamzan Tepe,[15] Karahan Tepe,[16] Harbetsuvan Tepesi,[17] Sefer Tepe,[14] and Taslı Tepe.[18] Other stone stelae—without the characteristic T shape—have been documented at contemporary sites further afield, including Çayönü, Qermez Dere, Boncuklu Tarla and Gusir Höyük.[19]

On the stelae, geometrical side-arms ending with hands are often sculpted in low-relief, suggesting that these pillars represent stylized anthropomorphic beings, the top of the "T" corresponding to the head. Belts and human clothing are also often sculpted as well.[11]

Totems

Totems combining humans and animals were found in Göbekli Tepe and in Nevalı Çori. The one in Nevalı Çori represent a bird, probably a vulture, standing on top of two human seated back-to-back.[12] The meaning of such totems is as yet unknown.[12]

Phallic symbolism

Phallic symbolism seems to be a prevalent characteristic of the art associated with the Taş Tepeler sites. Statues of men holding their erect penis can be seen from Yeni Mahalle (the famous Urfa Man statue), Göbekli Tepe, Harbetsuvan Tepesi,[20] Karahan Tepe or Sayburç.[21] It has even been argued that the stelae themselves may have been phallic representations of ancestors.[21] The figures also generally have a V-shaped collar around the neck.

Phallic symbolism may also be part of the general forcefully realistic style of the sculptures, as seen for example in Gobekli Tepe, with animals being typically shown with bared teeth, powerful paws, or long tusks, contributing to the threatening atmosphere of the monuments.[22]

-

Karahan Tepe Man, 10,000-9,500 BCE

Karahan Tepe Man, 10,000-9,500 BCE -

![Urfa Man, c. 9000 BCE.[23]](./_assets_/Urfa_man.jpg)

-

.jpg) Sayburç Man, 9th millennium BCE

Sayburç Man, 9th millennium BCE -

![Gobekli Tepe ityphallic protome.[24]](./_assets_/Gobekli_Tepe_ithyphallic_statuette._%C5%9Eanl%C4%B1urfa_-_Archeology_Museum%252C_July_2025_(frontal).jpg) Gobekli Tepe ityphallic protome.[24]

Gobekli Tepe ityphallic protome.[24]

Daily artifacts

Some of the sites of the Taş Tepeler culture have provided artifacts which are characteristic of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic or Neolithic periods. Ayanlar Höyük, an early to mid Pre-Pottery Neolithic B site had stone vessels and stone plates (typical utensils before the advent of pottery), some of them decorated with animal motifs, as well as grindstones.[25]

-

Stone vessels decorated with animal motif, Ayanlar Höyük (8800-7000 BCE)

Stone vessels decorated with animal motif, Ayanlar Höyük (8800-7000 BCE) -

Top and bottom grindstone from Ayanlar Höyük (8800-7000 BCE)

Top and bottom grindstone from Ayanlar Höyük (8800-7000 BCE) -

Blades and stone implements, Ayanlar Höyük (8800-7000 BCE)

Blades and stone implements, Ayanlar Höyük (8800-7000 BCE) -

.jpg) Stone necklace, Boncuklu Tarla (8800-6000 BCE)

Stone necklace, Boncuklu Tarla (8800-6000 BCE)

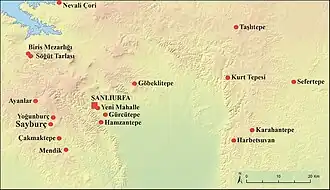

Sites

Monumental structures

The sites include Göbekli Tepe, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and at least eleven others: Nevalı Çori, Yeni Mahalle, Karahan Tepe, Hamzan Tepe, Sefer Tepe, Taşlı Tepe, Kurt Tepe, Harbetsuvan Tepe, Sayburç, Ayanlar Höyük,[26] Çakmaktepe.[2] They are currently being investigated and conserved under the 'Şanlıurfa Neolithic Research Project', a collaboration between Turkish and international researchers.[27][28]

Desert kites for animal hunting

Desert kites are associated or proximate with some of the sites.[3] These desert kites were extensive dry stone-wall structures, often several hundred meters in length, designed to mass-channel and trap wild-game such as gazelles. They are composed of long driving lines leading to a trap enclosure, often surrounded by a number of small cells.[3] In the Upper Mesopotamia region, these desert kites were likely contemporary with Göbekli Tepe, and suggest efforts at capturing and controlling animal populations, possibly with an intent to store and consume meat resources with a long-term perspective.[3] These desert kites can be understood as an early experiment towards sedentarism and domestication.[3] The study of desert kites is a part of the Taş Tepeler archaeological program run by the Turkish Ministry of Culture, with the intent to investigate the origins of sedentism and agropastoral lifeways in the region.[3]

Genetics

Human samples from Boncuklu Tarla (dated to 9000-8500 BCE), and Çayönü (dated to circa 8300-7500 BCE), were part of a recent genetic study, as members of a Mesopotamia_Neolithic cluster (together with a few Nemrik 9 samples).[29] In this study, the Mesopotamia_Neolithic cluster appeared as a major ancestry of several Levantine and Egyptian Bronze Age individuals, particularly from Ebla, Ashkalon, Baq'ah and Nuwayrat.[29]

.png)

The Nuwayrat individual in particular, an Old Kingdom adult male Egyptian of relatively high-status radiocarbon-dated to 2855–2570 BCE and dubbed "Old Kingdom individual (NUE001)", was found to be associated with North African Neolithic ancestry, but about 24% of his genetic ancestry could be sourced to the eastern Fertile Crescent, including Mesopotamia, corresponding to the Mesopotamia_Neolithic cluster.[31] The genetic profile was most closely represented by a two-source model, in which 77.6% ± 3.8% of the ancestry corresponded to genomes from the Middle Neolithic Moroccan site of Skhirat-Rouazi (dated to 4780–4230 BCE), which itself consists of predominantly (76.4 ± 4.0%) Levant Neolithic ancestry and (23.6 ± 4.0%) minor Iberomaurusian ancestry, while the remainder (22.4% ± 3.8%) was most closely related to known genomes from Neolithic Mesopotamia (dated to 9000-8000 BCE).[31][32] No other two-source model met the significance criteria (P>0.05). A total of two Three-source models also emerged, but had similar ancestry proportions, with the addition of a much smaller third-place component from the Neolithic/Chalcolithic Levant.[31] According to Lazardis, “What this sample does tell us is that at such an early date there were people in Egypt that were mostly North African in ancestry, but with some contribution of ancestry from Mesopotamia". According to Girdland-Flink, the fact that 20% of the man’s ancestry best matches older genomes from Mesopotamia, suggests that the movement of Mesopotamian people into Egypt may have been fairly substantial at some point.[33]

The timing of the admixture event cannot be calculated directly from the 2025 genetic study.[34] The 2025 study showed that the Nuwayrat sample had the greatest affinity with samples from Neolithic Mesopotamia dating to 9000-8000 BCE.[29][34] Concurrently, other studies have shown that during the Neolithic, in the 10,000-5,000 BCE period, populations from Mesopotamia and the Zagros expanded into the Near-East, particularly Anatolia, bringing with them the Neolithic package of technological innovation (domesticated plants, pottery, greater sedentism). Egypt may also have been affected by such migratory movements.[34][35] Further changes in odontometrics and dental tissues have been observed in the Nile Valley around 6000 BCE.[34] Subsequent cultural influxes from Mesopotamia are documented into the 4th millennium (3999-3000 BCE) with the appearance of Late Uruk features during the Late Pre-dynastic period of Egypt.[34]

Further reading

- Discovering a New Neolithic World at Archaeology Magazine

- Discover Stone Mounds App for audio guides of Taş Tepeler

Souces

- Çelik, Bahattin (2010). "Hamzan Tepe in the light of new finds". Documenta Praehistorica. 37: 257–268. doi:10.4312/dp.37.22.

- Celik, Bahattin (27 December 2017). "A new Pre-Pottery Neolithic site in Southeastern Turkey: Ayanlar Höyük (Gre Hut)". Documenta Praehistorica. 44: 360–367. doi:10.4312/dp.44.22. ISSN 1854-2492.

- Dietrich, Oliver (8 May 2016a). "The current distribution of sites with T-shaped pillars". Tepe Telegrams. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- Güler, Mustafa; Çelik, Bahattin; Güler, Gül (2012). "New pre-pottery neolithic settlements from Viranşehir District". Anadolu / Anatolia. 38: 164–80. doi:10.1501/Andl_0000000398.

- Peters, Joris; Schmidt, Klaus (2004). "Animals in the Symbolic World of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, South-eastern Turkey: A Preliminary Assessment". Anthropozoologica. 39.

References

- ^ "Türkiye illuminates its Neolithic Heritage with TAŞ TEPELER | TGA" (in Turkish). Archived from the original on 2023-08-24. Retrieved 2022-05-28.

- ^ a b Ayala, Gianna; Wainwright, John; Farid, Shahina; Kabukcu, Ceren; Karul, Necmi (2023). "Past environments in the transition to agriculture: preliminary investigations in the Taş Tepeler landscape" (PDF). Heritage Türkiye. 13. British Institute of Archaeology at Ankara: 35. doi:10.18866/biaa2023.19.

- ^ a b c d e f Şahin, Fatma; Massa, Michele (February 2025). "Mass-hunting in South-west Asia at the dawn of sedentism: new evidence from Şanlıurfa, south-east Türkiye". Antiquity. 99 (403). Cambridge University Press: Introduction. doi:10.15184/aqy.2024.155.

- ^ a b c d e Taracha, Piotr (2009). Religions of Second Millennium Anatolia. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 12–14. ISBN 978-3-447-05885-8.

- ^ a b Ayaz, Orhan (1 January 2023). "An Alternative View on Animal Symbolism in The Göbekli Tepe Neolithic Cultural Region in the Light of New Data (Göbekli Tepe, Sayburç)". Iğdır Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi: 271-272, Fig.6. doi:10.54600/IGDIRSOSBILDER.1252928.

- ^ Ervynck, A.; et al. (2001). "Born Free? New Evidence for the Status of Sus scrofa at Neolithic Çayönü Tepesi (Southeastern Anatolia, Turkey)". Paléorient. 27 (2): 47–73. doi:10.3406/paleo.2001.4731. JSTOR 41496617.

- ^ Taracha, Piotr (2009). Religions of Second Millennium Anatolia. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 8. ISBN 978-3-447-05885-8.

- ^ Zeder, Melinda A. (19 August 2008). "Domestication and early agriculture in the Mediterranean Basin: Origins, diffusion, and impact". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (33): 11597–11604, Fig.1. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801317105.

- ^ Ayaz, Orhan (1 January 2023). "An Alternative View on Animal Symbolism in The Göbekli Tepe Neolithic Cultural Region in the Light of New Data (Göbekli Tepe, Sayburç)". Iğdır Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi: 372. doi:10.54600/IGDIRSOSBILDER.1252928.

- ^ Ayaz, Orhan (1 January 2023). "An Alternative View on Animal Symbolism in The Göbekli Tepe Neolithic Cultural Region in the Light of New Data (Göbekli Tepe, Sayburç)". Iğdır Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi: 374. doi:10.54600/IGDIRSOSBILDER.1252928.

If we consider both compositions as two parts of a single narrative, the second depiction should be associated with rituals related to a person who comes out victorious from an encounter with an aurochs (and depiction with a phallus suggests the ritual in question can be an initiation rite). Thus, the depiction related with the bull-human encounter should reflect not the "human in struggle against the power of nature" as interpreted by Özdoğan and Uludağ (2022: 22), but the control of human over nature (and therefore, animals) (Fig. 7). Given the data on this cultural region, it is perfectly reasonable to assume that the first part of the story is related to animals held in entrapment areas.

- ^ a b Peters & Schmidt 2004, pp. 182, 188.

- ^ a b c Schmidt, Klaus (2010). "Göbekli Tepe – the Stone Age Sanctuaries.New results of ongoing excavations with a special focuson sculptures and high reliefs". Documenta Praehistorica (XXXVII): 248.

- ^ "Turkey's Taş Tepeler marks the beginning of civilization". Arkeonews. 13 October 2021.

- ^ a b Güler, Çelik & Güler 2012.

- ^ Çelik 2010.

- ^ Çelik 2011.

- ^ Çelik 2016.

- ^ Güler, Çelik & Güler 2013.

- ^ Dietrich 2016a.

- ^ Altuntas, Leman (21 May 2022). ""Harbetsuvan Tepe", the 10,000-year-old Neolithic Acropolis of Taş Tepeler". Arkeonews.

- ^ a b Ayaz, Orhan (30 June 2023). "Self-Revelation: An Origin Myth Interpretation of the Göbekli Tepe Culture (An Alternative Perspective on Anthropomorphic Themes)". Yüzüncü Yıl Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi (60): 196–198. doi:10.53568/yyusbed.1233144.

- ^ Benz, Marion; Bauer, Joachim (2013). "Symbols of Power - Symbols of Crisis? A Psycho-Social Approach to Early Neolithic Symbol Systems". Neo-Lithics Special Issue: 14.

- ^ CEli̇K, Bahattin (15 June 2014). "ŞANLIURFA BÖLGESİNDE "T" ŞEKLİNDE DİKMETAŞ BULUNAN YERLEŞİMLERİN FARKLILIK VE BENZERLİKLERİ". Türkiye Bilimler Akademisi Arkeoloji Dergisi (17): 19–20. doi:10.22520/tubaar.2014.0001.

- ^ Peters & Schmidt 2004, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Celik 2017.

- ^ "Features - Discovering a New Neolithic World - Archaeology Magazine - March/April 2024". Archaeology Magazine. Retrieved 2025-04-29.

- ^ "Karahantepe | Taş Tepeler". tastepeler.org. Retrieved 2025-04-29.

- ^ "Sefertepe | Taş Tepeler". tastepeler.org. Retrieved 2025-04-29.

- ^ a b c d Morez Jacobs et al. 2025, p. 4 fig.3c, Supplement Tables S3.

- ^ Morez Jacobs et al. 2025, p. 4, Fig.3a.

- ^ a b c Morez Jacobs et al. 2025.

- ^ Simões, Luciana G.; Günther, Torsten; Martínez-Sánchez, Rafael M.; Vera-Rodríguez, Juan Carlos; Iriarte, Eneko; Rodríguez-Varela, Ricardo; Bokbot, Youssef; Valdiosera, Cristina; Jakobsson, Mattias (7 June 2023). "Northwest African Neolithic initiated by migrants from Iberia and Levant". Nature. 618 (7965): 550–556. doi:10.1038/s41586-023-06166-6. PMC 10266975. PMID 37286608.

- ^ Strickland, Ashley (2 July 2025). "The first genome sequenced from ancient Egypt reveals surprising ancestry, scientists say". CNN.

- ^ a b c d e Morez Jacobs et al. 2025, p. 6.

- ^ Lazaridis, Iosif; Alpaslan-Roodenberg, Songül (2022). "Ancient DNA from Mesopotamia suggests distinct Pre-Pottery and Pottery Neolithic migrations into Anatolia" (PDF). Science (377): 982–987.