Suebi

The Suebi (also spelled Suevi or Suavi) were a large group of Germanic peoples first reported by Julius Caesar and other Roman authors in the 1st century BC. They originated near the Elbe River in what is now eastern Germany, but related Suebian groups spread across central Europe, and from the 5th century reached as far as Spain, Portugal and Italy. Archaeologically, the Suebi are associated with the Jastorf culture and Przeworsk culture, and linguistically with early "Elbe Germanic" dialects. Their speech is considered ancestral to later High German varieties, especially Alemannic and Bavarian.[1]

In the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, a powerful Suebian alliance, led by the Marcomanni and Quadi near the Middle Danube, maintained a tense balance with the Roman empire. After their defeat in the destructive Marcomannic Wars of the late 2nd century, many Suebi moved into the Roman Empire, while others regrouped closer to the Roman frontier. The Alamanni and Juthungi, for example, settled in what became medieval Swabia, a cultural region in southern Germany that still bears their name.

After the Battle of Adrianople (378), the remaining Suebi of the Middle Danube were unsettled by the large-scale arrival of Huns, Goths, Alans, and other newcomers from eastern Europe. Some Suebi entered the empire or moved west; others allied with Attila and later formed a short-lived Kingdom of the Suevi after his death in 453. In this period, Suebian groups in the Danubian area contributed to the ethnogenesis of the Bavarians, Swabians, and the Lombards of Italy.

In about 406, another large Suebian group moved west into Gaul and then Hispania, where they established the Kingdom of the Suebi in Gallaecia (north-west Iberia). This polity lasted from 409 to 585. It was eventually absorbed by the Visigoths, but its legacy survives in local place-names and in the historical identity of Galicia and northern Portugal.

Etymology

The spelling form "Suebi" is the dominant one in classical times, while the common variant "Suevi" also appears throughout history. Around 300-600 AD spellings such as Suaevi, Suavi, and Σούαβοι started to occur, because of a sound shift which occurred in West Germanic at this time. However, the classical spellings also continued to be used.[2] The Proto-Germanic pronunciation is reconstructed as *Swēbōz.[3]

Throughout the 19th century, numerous attempts to propose a Germanic etymology for the name were made which are no longer accepted by scholars. The most widely accepted proposal today is that the word is related to a reconstructed Germanic adjective *swēsa- meaning “one’s own", which is also found in other ethnic names including the Germanic Suiones (Swedes).[3]

The similarity between the Suebian name and the reconstructed Germanic word *sebjō meaning "clan", “related" or "family” is generally seen as indicating that the two words are related, and this is seen as relevant for attempts to explain the second part name.[3] Notably, the name of the Semnones, who classical authors described as the most prestigious and original Suebians, may also have a similar etymology. Linguists generally believe that this name was pronounced as Sebnō, and derived from Proto Indo-European *swe-bh(o)- meaning “of one’s own kind”, but in this case with an n-suffix that expresses belonging. The Suebi would then be “those who are of their own kind”, while the Semnones would be “those who belong to those of their own kind”.[4]

In contrast, Rübekeil argues that the relevant Proto Indo-European suffix to explain the Germanic name of the Suebi is not -bho, which was a suffix used to create adverbs from adjectives, but *-bū- “to be”.[3] According to him, the most elegant solution, which would also explained the vowel length, would involve a Proto Indo-European root noun *swe-bhū- meaning roughly “self-being”, and a syllabic lengthening which changed the meaning to “belonging to”.[5]

Alternatively, it may be borrowed from a Celtic word for "vagabond".[6]

One people, or many peoples

In Caesar's first report in 58 BC, the Suebi were a single tribe, who lived in a specific place, between the Ubii and Cherusci, somewhere between the Rhine and Elbe. This Suebi tribe were described again in the following generation, when several classical sources describe their crushing defeat by Drusus the elder in 9 BC. Like Caesar, these authors mentioned the Marcomanni as a distinct allied people who were also defeated in the Roman victories of both 58 BC and 9 BC.[7][8][9][10]

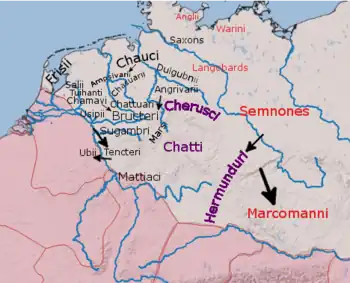

After the many victories of Rome in Germania, first century authors such as Strabo, Pliny the Elder, and Tacitus began to perceive the Suebi as a group of tribes, rather than a single tribe. Strabo, writing in about 23 AD, described the Suebi not only as the largest nation (ἔθνος) of the region between Rhine and Elbe, stretching from the one river to the other, but also as an umbrella category including large, well-known tribes such as the Semnones, Hermunduri, and Langobardi as Suebi. Several of these peoples were now being led by Maroboduus, the king of the Marcomanni.[11]

Tacitus, writing around 100 AD, agreed that the Suebi "are not one single tribe (Latin: gens)", and that "they occupy a larger part of Germania, and though still divided into distinct nations and names" (Latin: propriis adhuc nationibus nominibusque discreti), they are commonly referred to as Suebi".[12] Tacitus noted that the Semnones, who lived on the Elbe, were believed to be the leaders (Latin: caput), and origin of the Suebian nation (Latin: initia gentis). Like the Suebi described by Caesar they lived in 100 pagi. Their reputation was reinforced by their sacred grove where "all the tribes (Latin: populi) of the same name and blood come together", referring to all Suebi, and not just all Semnones.[13] Nevertheless, the Marcomanni "stand first in strength and renown".[14]

According to Tacitus, apart from the Suebi living near the Romans, nearly all peoples living between the Elbe and Vistula, and north into Scandinavia were Suebi. In modern scholarship it has sometimes alternatively been proposed that the name "Suebi" may have even been the name of the Germani for themselves, as opposed to the Latin name "Germani", while in contrast others have seen the popularity of the term as an umbrella category as a Roman-driven tendency. The term was handy for referring to tribes whose name was not clear.[15] It has also been claimed by Herwig Wolfram that in the first centuries AD, classical ethnography applied the name Suevi to so many Germanic tribes that it almost replaced the term Germani which Caesar had made popular.[16]

By the second century however, Roman sources used the term less for several centuries, perhaps because they were now better informed about the names of individual tribes.[15][17] In the late fourth century, as the Quadi and Marcomanni disappear from the record, apparently participating in migrations into various parts of the Roman empire, or in some cases within the empire of Attila, the more generic term Suebi makes a return in Roman documents, and several new Suebian polities came into being.[18]

Language

While there is uncertainty about whether all tribes identified by Romans as Germani spoke what would now be considered a Germanic language, the Suebi are generally agreed to have spoken one or more Germanic languages. In particular, the Suebi are associated with the concept of an "Elbe Germanic" group of early dialects spoken by the Irminones, entering Germany from the east, and originating on the Baltic. In late classical times, the Suebian dialects in central Europe experienced the High German consonant shift that defines modern High German languages, and in its most extreme form, Upper German.[19]

Modern Swabian German, and Alemannic German more broadly, are therefore "assumed to have evolved at least in part" from Suebian.[20] However, Bavarian, the Thuringian dialect, the Lombardic language spoken by the Lombards of Italy, and standard "High German" itself, are also at least partly derived from the dialects spoken by the Suebi.[19]

The modern term "Elbe Germanic" covers a large grouping of early Germanic peoples that overlaps with the classical category "Suevi" and "Irminones". However, this term was developed mainly as an attempt to define the ancient peoples who must have spoken the Germanic dialects that led to modern Upper German dialects spoken in Austria, Bavaria, Thuringia, Alsace, Baden-Württemberg and German speaking Switzerland. This was proposed by Friedrich Maurer as one of five major Kulturkreise or "culture-groups" whose dialects developed in the southern German area from the first century BC through to the fourth century AD.[21] Apart from his own linguistic work with modern dialects, he also referred to the archaeological and literary analysis of Germanic tribes done earlier by Gustaf Kossinna[22] In terms of these proposed ancient dialects, the Vandals, Goths and Burgundians are generally referred to as members of the Eastern Germanic group, distinct from the Elbe Germanic.

Classical ethnography

In his account of the Gallic Wars, Julius Caesar first noted the important role of Suebian forces in the invasion of Gaul in 58 BC, which was led by king Ariovistus, whose wife was Suebian.[23] This invasion played a special role in the way Caesar tried to justify the controversial mission creep of his campaign in Gaul. Caesar helped create an important tradition of emphasizing the dedication to war of these northern barbarians from beyond the Rhine. He emphasised their hard but noble way of life, and contrasted it to the soft Mediterranean way of living. Although Strabo and Tacitus, unlike Caesar, understood the Suebi to be a large group of peoples including the Marcomanni, instead of one tribe, they continued Caesar's tradition of emphasizing how impressive and dangerous the Suebi were.

Caesar wrote a special digression about them, emphasizing their potential danger to Rome. Caesar called them the largest and the most warlike nation (Latin: gens) of all the Germanic peoples (Latin: Germani). They were constantly engaged in war, animal husbandry, and hunting. They had little agriculture, with no private ownership of land, and a rule against living in one place for more than one year. They were divided into 100 countries (Latin: pagi), each of which could supply a thousand men for military campaigns which were sent out every year.[24] They were powerful enough to force the peoples near them to keep a large swathe of lands around them unoccupied.[25]

Strabo seems to have had Caesar's report in mind when he contrasted the Suebi with more settled and agricultural tribes such as the Chatti and Cherusci, saying that "they do not till the soil or even store up food, but live in small huts that are merely temporary structures; and they live for the most part off their flocks, as the Nomads do, so that, in imitation of the Nomads, they load their household belongings on their wagons and with their beasts turn whithersoever they think best".[26]

Tacitus wrote a more detailed work, his Germania, which continued the theme of showing how the Germani, and especially the Suebi, were constantly preparing for war. He associated the Suebi with the so-called "Suebian knot", the fashion of pulling back their hair, and tying it in a knot. According to Tacitus, this fashion was not restricted to the Suebi, but he believed that young people in other tribes had imitated them, and the fashion helped the Suebi distinguish themselves from both other Germani, and from their slaves. The nobles had taller and more elaborate knots in order to increase their stature and to strike fear. Modern historians do not think that these knots were a reliable indicator of ethnicity.[27] He also described how the Suebians attended rituals involving human sacrifice, in the land of the Semnones.[28]

Historical events

The Gaulish campaigns of Julius Caesar

In 58 BC Julius Caesar (100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) confronted a large army led by a king named Ariovistus. The population which he ruled had already been settled for some years in Gaul, having arrived at the invitation of a local tribe, the Sequani, who lived between the Saône and the Jura Mountains which now form the border between France and Switzerland. Ariovistus had helped fight against another local tribe, the Aedui, who lived west of the Saône. Ariovistus had already been recognized as a king by the Roman senate. Caesar on the other hand entered into the conflict to defend the Aedui. As part of his justification for intervention into Gaul Caesar was the first author to make a distinction between peoples from west of the Rhine in Gaul, and the Germani (or Germanic peoples) from east of the Rhine, who he argued to be a potential source of continuing invasions that would affect Italy.

When Caesar arrived in the area, ambassadors from the Treviri, who lived further north near the Moselle, arrived to report that 100 pagi of Suebi had been led to the Rhine by two brothers, Nasuas and Cimberius. Caesar to move quickly in order to try to avoid the joining of forces.[29] Other Suebi appear among the peoples Caesar listed in the battle line-up of Ariovistus himself: "Harudes, Marcomanni, Tribocci, Vangiones, Nemetes, Sedusii, and Suevi".[30] Caesar defeated Ariovistus in battle, forcing him to escape across the Rhine. When news of this spread, the fresh Suebian forces turned back in some panic, and the Ubii who lived on the east bank near modern Cologne took advantage of the situation to attack them.[31]

In 55 BC, having escalated his intervention into a conquest of all of Gaul for Rome, Caesar decided to confront the Suebi in their own country east of the Rhine. One reason is that the Ubii, who were neighbours of the Suebi, sent ambassadors and proposed such a crossing. Another reason was that the Tencteri and Usipetes, who were already forced from their homes, had tried to cross the Rhine and enter Gaul by force, but after coming into bloody conflict with Caesar many had now sought refuge among the Sugambri, north of the Ubii.[32] Caesar bridged the Rhine, the first known to do so. The Suebi abandoned their towns closest to the Romans, retreated to the forest and assembled an army. Caesar moved back across the bridge and broke it down, stating that he had achieved his objective of warning the Suebi. They in turn supposedly stopped harassing the Ubii. In the time of Augustus the Ubii were later resettled on the west bank of the Rhine, in Roman territory.

In 53 BC Caesar found that the Treviri had received auxiliary forces from the Suebi, and he once again bridged the Rhine but this time established a fort. Ubian spies gave him updates about the movements of the Suebi.[33]

The Germanic campaigns of Augustus

Archaeological evidence implies the replacement of the older La Tène culture culture east of the Rhine, which had been similar to the cultures found in Gaul. This is consistent with the reports of disruption in these areas given by Caesar and Strabo.[34] This may have already begun before his arrival in the area.[35] Nearer to the Rhine, archaeological materials consistent with Elbe origins begin to appear already on the southern Main river around 0 AD, and on the Neckar some decades later, and other communities between the Main, Rhine and Danube formed later. The exact nature of their relationship with the incoming Romans is unknown, but within generations these communities were using Roman technologies, and the Neckar Suebi, as they were known, were recognized as a Roman civitas.[36]

Shortly before 29 BC, the Suebi crossed the Rhine, and were defeated by the Roman governor in Gaul, Gaius Carrinas. Along with the young Octavian Caesar (the future Augustus), Carrinas celebrated a triumph in 29 BC.[8] Shortly afterwards, captured Suebians fought as gladiators against captured Dacians at Rome.

In 9 BC, the Suebi were defeated by Drusus the Elder, who had already defeated several other peoples including the Marcomanni. Florus reported that the Cherusci, Suebi and Sicambri formed an alliance marked by the crucifixion of twenty Roman centurions. Drusus defeated them with great difficulty, and then confiscated their plunder and sold them into slavery so that "there was such peace in Germany that the inhabitants seemed changed", "the very climate milder and softer than it used to be".[7] Suetonius reported that the Suebi and Sugambri "were taken into Gaul and settled in lands near the Rhine" while other Germani were pushed "to the farther side of the river Albis" (Elbe).[10] Elsewhere Suetonius mentioned that in Germania the future emperor Tiberius settled 40,000 prisoners of war. Possibly these were settled near the bank of the Rhine.[37]

Orosius claimed that the Marcomanni were nearly wiped out after their defeat during this campaign.[9] In the Res Gestae Divi Augusti which celebrates the reign of Augustus, it is boasted that among the many kings who took refuge with Augustus as suppliants, there was a king of the Marcomanni Suebi. The name of this king is no longer legible on the Monumentum Ancyranum, but it ended with "-rus".[38]

After these major defeats, the Marcomanni and many Suebi came under the leadership of King Maroboduus, a member of the Marcomanni royal family who had grown up in Rome. Tacitus even calls him a king of the Suebi.[39] Strabo described how he led his people into the Hercynian forest and established his royal capital at Buiaimon (somewhere in or near Bohemia, which still carries the name). He noted that Suebi lived both in the forest, and outside of it.[40] Velleius Paterculus described Boiohaemum, where Maroboduus and the Marcomanni lived, as "plains surrounded by the Hercynian forest", and he said this was the only part of Germania which the Romans did not control in the period before the Roman defeat at the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 AD.[41]

Velleius said that Maroboduus drilled his Bohemian soldiers to almost Roman standards, and that although his policy was to avoid conflict with Rome, the Romans came to be concerned that he could invade Italy. "Races and individuals who revolted from us [the Romans] found in him a refuge." From a Roman point of view he noted that the closest point of access for an attack upon Bohemia would be via Carnuntum.[42] This was between present-day Vienna and Bratislava, where the Morava river enters the Danube. However, just when legions were being gathered for a two-pronged attack upon the Marcomanni the Great Illyrian revolt broke out, affecting the Roman provinces south of the Marcomanni from 6-9 AD.[43]

No sooner had the Illyrian wars been ended in 9 AD when Rome's dominance of the land northwest of the Marcomanni, between Rhine and Elbe, was also severely checked by the rebellion of the Cherusci and their allies. This began with the annihilation of three legions at the Battle of Teutoburg Forest. The kingdom of the Marcomanni and their allies stayed out of the conflict, and when Maroboduus was sent the head of the defeated Roman leader Varus, he sent it on to Rome for burial. Augustus assigned Germanicus, the son of Drusus the Elder, to lead the Roman forces on the Rhine, but the emperor died in 14 AD.

Roman relations after Augustus

Germanicus fought for three years against the Cherusci and their allies. He defeated Arminius, but did not capture or kill him. The new emperor Tiberius however didn't seek to install a Roman administration in Germania, and Germanicus was recalled. Instead the Romans acted to sow discord between the Germani themselves. The Langobardi and Semnones, Suebi living on the Elbe not far from the Cherusci, defected from the kingdom of Maroboduus in the name of freedom, both because Maroboduus did not support the revolt, and because they objected to his royal power.[44]

In 17 AD war broke out among these two alliances of Germanic peoples, led by Arminius and Maroboduus. Maroboduus requested help from Rome but according to Tacitus the Romans claimed that Maroboduus "had no right to invoke the aid of Roman arms against the Cherusci, when he had rendered no assistance to the Romans in their conflict with the same enemy". After an indecisive battle, Maroboduus withdrew into the hilly forests of Bohemia in 18 AD.[45] The Romans urged the Germani "to complete the destruction of the now broken power of Maroboduus".[46] This was all in line with the new foreign policy of the emperor Tiberius.[47]

In 19 AD, Maroboduus was deposed and exiled by Catualda, who was a prince who had been living in exile among the Gutones on the Baltic coast, in what is now northern Poland. (Tacitus claims that the Gutones were more accepting of royalty than most Germani.) Maroboduus went into exile among the Romans and lived another 18 years in Ravenna.[47] Catualda's victory was short-lived. He was in turn deposed by Vibilius of the Hermunduri that same year he came to power, 19 AD. The subjects of Maroboduus and Catualda, presumably mainly Marcomanni, were moved by the Romans to an area near the Danube, between the Morava and "Cusus" rivers, and placed under the control of the Quadian king Vannius. The area where Vannius ruled over the Marcomanni exiles is generally considered to have been a state distinct from the old Quadi kingdom itself. Unfortunately the Cusus river has not been identified with certainty. However, Slovak archaeological research locates a core area of the Vannius kingdom was probably in the fertile southwestern Slovakian lowlands around Trnava, east of the Little Carpathians.[48]

Vannius personally benefitted from the new situation and became very wealthy and unpopular. He was himself eventually also deposed by Vibilius and the Hermunduri, working together with the Lugii from the north, in 50/51 AD. This revolt by Vibilius was coordinated with the nephews of Vannius, Vangio and Sido, who then divided his realm between themselves as loyal Roman client kings.[49] Vannius was defeated and fled with his followers across the Danube, where they were assigned land in Roman Pannonia. This settlement is associated with Germanic finds from the 1st century AD in Burgenland, west of Lake Neusiedl.[48]

In 69 AD, the "Year of the Four Emperors", two kings named Sido and Italicus, the latter perhaps the son of Vangio, fought on the side of Vespasian in a Roman civil war. Tacitus described them as kings of the Suebi, and emphasized their loyalty to Rome. They were present at the second battle of Bedriacum in 69 AD at Cremona.[50]

The relationship between the Suebi and Romans stabilized but was interrupted under emperor Domitian during the years 89-97 AD, after the Quadi and Marcomanni refused to assist in a conflict against the Dacians. In 89 AD Domitian entered Pannonia to make war, killed the peace envoys sent to him, and was then defeated by the Marcomanni. This campaign was referred to as the war against the Suebi, or the Suebi and Sarmatians, or the Marcomanni, Quadi and Sarmatians. The relationship then stabilized again in the time of emperor Nerva (reigned 96-98).[51] Writing in this period, Tacitus noted that both the Marcomanni and their neighbours the Quadi still had "kings of their own nation, descended from the noble stock of Maroboduus and Tudrus". However, he noted that they submit to foreigners, and their strength and power depend on Roman influence. Rome supports them by arms, and "more frequently by our money".[52] To the west of the Marcomanni, Tacitus placed two other powerful Suebian states, the Hermunduri, whose lands were concentrated in Bohemia near the sources of the Elbe, but they were also allowed to settle and trade as far as the Danubian border in Roman Raetia in present day Bavaria. Between the Hermunduri and Marcomanni north of the Danube were also the Naristi (also known as the Varisti).

Marcomannic wars

The relationship between the Romans and the Suebian alliance was seriously disrupted and permanently changed during the long series of conflicts called the Marcomannic or Germanic wars, which were fought mainly during the rule of emperor Marcus Aurelius (reigned 161-180 AD). It was triggered by a raid across the Danube in the 150s or 160s AD, by Suebian Langobardi, together with Obii whose identity is uncertain.

A group of the nations living north of the Danube border selected Ballomarius, king of the Marcomanni, and ten other national representatives, to go on a peace mission to the governor of Roman Pannonia. Oaths were sworn and the envoys returned home.[53] The Romans were apparently planning for a Germania campaign, and knew that Italy itself was threatened by these peoples, but were deliberately diplomatic while they were occupied with the Parthian campaign in the Middle East, and badly affected by the Antonine plague.

Although a Roman offensive could not start in 167 AD, two new legions were raised and in 168 AD the two emperors, Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius, set out to cross the alps. Either in 167 AD, before the Romans setting, or in 169 AD, after the Romans came to a stop when Verus died, the Marcomanni and Quadi led a crossing of the Danube, and an attack into Italy itself. They destroyed Opitergium (present-day Oderzo) and put the important town of Aquileia under siege. Whatever the exact sequence of events, the Historia Augusta says that with the Romans in action several kings of the barbarians retreated, and some of the barbarians put anti-Roman leaders to death. In particular, the Quadi, having lost their king, announced they would not confirm an elected successor without approval from the emperors.[54]

Marcus Aurelius returned to Rome but headed north again in the autumn of 169. He established a Danubian headquarters in Carnuntum between present-day Vienna and Bratislava. From here he could receive embassies from the different peoples north of the Danube. Some were given the possibility to settle in the empire, others were recruited to fight on the Roman side. The Quadi were pacified, and in 171 AD they agreed to leave their coalition, and returned deserters, and 13,000 prisoners of war. They supplied horses and cattle as war contributions, and promised not to allow Marcomanni or Iazyges passage through their territory. By 173 AD the Quadi had rebelled again, and they expelled their Roman-approved king Furtius, replacing with Ariogaisos.[55][56] In a major battle between 172 and 174 AD, a Roman force was almost defeated, until a sudden rainstorm allowed them to defeat the Quadi.[55] The incident is well-known because of the account given by Dio Cassius, and on the Column of Marcus Aurelius in Rome.[56] By 175 AD the cavalry from the Marcomanni, Naristae, and Quadi were forced to travel to the Middle East, and in 176 AD Marcus Aurelius and his son Commodus held a triumph as victors over Germania and Sarmatia.[55]

The situation remained disturbed in subsequent years. The Romans declared a new war in 177 AD and set off in 178 AD, naming the Marcomanni, Hermunduri, Sarmatians, and Quadi as specific enemies.[57] Rome executed a successful and decisive battle against them in 179 AD at Laugaricio (present-day Trenčín in Slovakia) under the command of legate and procurator Marcus Valerius Maximianus.[56] By 180 AD the Quadi and Marcomanni were in a state of occupation, with Roman garrisons of 20,000 men each permanently stationed in both countries. The Romans even blocked the mountain passes so that they could not migrate north to live with the Suebian Semnones, breaking a link between the Suebian peoples which had apparently remained important for centuries. Marcus Aurelius was considering the creation of a new imperial province called Marcomannia when he died in 180, but this never happened.[58][59]

Commodus the son of Marcus Aurelius made peace soon after the death of his father in 180 AD, but he did not go ahead with plans to create a new Roman province. Some Marcomanni were subsequently settled in Italy and other parts of the empire, while others were forced to serve in the military.[60] After these wars the Marcomanni are mentioned much less in written records, and their western neighbours the fate of their previously powerful Suebian neighbours to the west, the Hermunduri and Varisti is unknown.

Third century Roman crisis and tetrarchy

The long Marcomannic wars in the second century created a new situation which eventually involved a major crisis for Rome and its neighbours, with Rome losing control of its large territories north of the Danube. After the heavy defeat of the Suebian alliance the Suebian Hermunduri and Naristi who lived near the Danube, west of the Marcomanni, no longer appear in the written record at all, and there are fewer mentions of the Marcomanni. Some of these populations were settled within the empire. The Quadi on the other hand attempted to move northwards to the land of their fellow Suebi on the Elbe, the Semnones, but the Roman military blocked the mountain passes to prevent this. The Quadi became more integrated with their non-Suebian eastern neighbours the Sarmatians.[61]

Roman treatment of the remaining Danubian Suebi was oppressive. Around 214/215 AD, Dio Cassius reported that because of raids into Pannonia, the emperor Caracalla invited the Quadi king Gaiobomarus to meet him, and then had him executed. According to this report Caracalla "claimed that he had overcome the recklessness, greed, and treachery of the Germans by deceit, since these qualities could not be conquered by force", and he was proud of the "enmity with the Vandili and the Marcomani, who had been friends, and in having executed Gaïobomarus".[62]

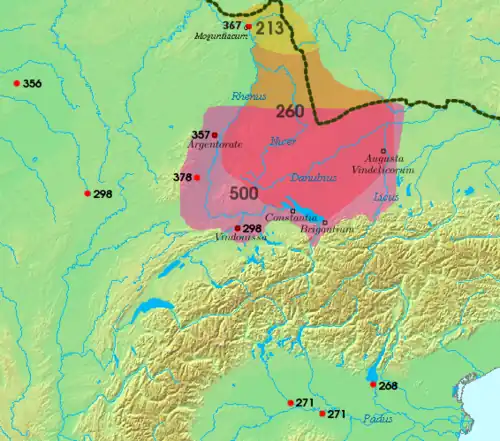

Where the Hermunduri and Naristi had lived, in what is now southern Germany, the Romans reported raiders crossing the Danube. In 213, the emperor Caracalla defeated a group of Germani who lived near the Raetian border on the Danube. According to later citations of Dio Cassius these Germani were the same as the people later called the Alamanni, which if correct would be their first appearance in history.[63] They were a large and diverse group containing many smaller groups with their own names and leaders. Archaeological evidence helps show a steady stream of people from Suebian areas outside the empire, including both the Elbe and Danube regions. They moved to areas in and near the Roman-controlled Agri Decumates between Rhine and Danube. A relatively dispersed population of Romanised Suebi had long been living there under Roman governance.[64] During the third century, the Romans gave up control of this territory.

In 233 Germani on the Raetian border once again made major inroads across the Danube into the empire, and this led indirectly to the assassination of the emperor Severus Alexander in 235, whose reaction was seen as insufficient. This initiated the 50-year period of Roman weakness and disunity known as the crisis of the third century. The new emperor Maximinus Thrax defeated these Germani and recovered the borders, with great losses. Throughout the century the Rhine and Danube continued to be crossed by Germani, meaning not only the Alamanni, but also the non-Suebian Franks to their north.

Further east the Goths were a new and powerful presence in what is now Ukraine, who began to have a very large impact on the Romans and their neighbours. Although never called Germani in Roman sources, they may have originated among the Gutones, who had been based at the mouth of the Vistula in the first century, where they were a wealthy node in the old Marcomanni network, trading amber and furs with the Mediterranean. If so, then their transformation into a large Scythian people of the eastern plains may have been influenced by the Marcomanni wars and Roman abandonment of Dacia. The 6th century writer Jordanes believed that the Romans were paying off Goths in this period under the rule of Ostrogotha. The Roman emperor Philip the Arab, who reigned 244-249 AD, attempted to cut these payments off, but major raids ensued. According to Jordanes the Marcomanni were also paying tribute to this same Gothic king, and the princes of the Quadi were effectively slaves of the Goths.

During the reign of Valerian (253-260 AD) the later historian Zosimus reported that the Marcomanni made excursions at the same time as those of the "Scythians", including Goths and their allies from the east. The Marcomanni made inroads into all the countries adjacent to the Danube, and laid Thessalonica waste.[65] Valerian's son Gallienus (reigned 253-268 AD) settled the Marcomanni within the Roman province of Pannonia Superior, south of the Danube. He also took Pipa or Pipara, the daughter of the Marcomanni king, Attalus, as a concubine.[66]

By the middle of the third century the Quadi seem to have rejected their client relationship with Rome, and they began a series of attacks which they organized together with their eastern neighbours the Sarmatians. Together they repeatedly attacked Illyricum. There was a Roman campaign against the Quadi in 283-284 AD, and the emperors Carinus (co-emperor 283-285) and Numerian (co-emperor 284-285) celebrated two personal triumphs each in 283 and 284. Nevertheless the Quadi were again mentioned among attacking Germanic tribes in 285 AD.[67]

Further west, in 260 the Romans recorded a victory over the Juthungi near modern Augsburg, south of the Danube, and a monument created to celebrate this described these Juthungi as Semnones, a Suebian people from the Elbe. In the 4th century, Marcellinus Ammianus described the Juthungi as a one of the peoples making up the Alamanni.[68] In the whole region between the Main, Rhine, Danube and Elbe rivers Suebian peoples were moving closer to the Roman borders, and sometimes raiding across them or even settling within the empire. The disrupted situation in the east was causing not only Suebi, but also people from further east such as the Burgundians and Vandals, also now came into direct conflict with Roman forces in this region during the reign of Probus (emperor 276-282).

Under Diocletian and his co-emperors, the so-called Tetrarchy, the Romans also began to recover control of their border regions. Their successes were celebrated in the Latin Panegyrics which are the first contemporary records which certainly refer to Franks and Alamanni using those terms. The Alamanni are mentioned in the "10th" panegyric of 289, which was dedicated to emperor Maximian. It mentions that in 287 the Alamanni joined forces with the Burgundians, a people from near the Vistula, in order to invade Gaul. Maximian defeated them by "divine foresight rather than by force". The invaders' "great numbers were ruinous to them", and famine ensued, allowing the emperor to capture them with smaller bands of troops.[69] A few years later the 11th panegyric of 291, also dedicated to Maximian, celebrated the way in which non-Romans were now driven to fight each other. One example it gives is that the Burgundians had been defeated by the Goths, presumably near the Vistula, somehow requiring the Alamanni to take up arms, perhaps as allies, or perhaps because the Burgundians were moving west. It also states that the Burgundians took land from the Alamanni, which the Alamanni now wanted to recover.[70]

In 297/298, Constantius Chlorus, Maximian's son-in-law and subordinate "caesar" in the tetrarchy, devastated the country of "Alamannia", which is the first mention of such a country in any surviving contemporary record. Between 298 and 302 he achieved further major victories against the Alamanni, who had been making inroads into Gaul itself. He defeated them in present-day Langres in France, and then Windisch in Switzerland.[71] The Quadi also seem to have been pacified in the time of Maximian's co-emperor to the east, Diocletian (reigned 284-305).[67] Although the details are not clear, Diocletian also claimed a triumph over the Marcomanni in 299 AD.[66]

Fourth century until 378

After the resignation of the co-emperors Diocletian and Maximian in 305 AD, and the death of Maximian's replacement as western emperor Constantius Chlorus in 306 AD, Constantine I, the son of Constantius, was proclaimed emperor by his army while based in at York in Britain. Among the forces supporting him there were the Alamanni, led by their king Chrocus. Constantine reigned from 306-337 AD.

The Rhine defences were weakened again in 355 when Magnentius became a rebel emperor based there. He killed Constans I, and took control of much of the western empire, battling the brother of Constans, Constantius II for control. During his revolt, which lasted until 353, the Rhine borders were undermanned and barbarians were able to enter Gaul while major battles were fought elsewhere. Magnentius finally died in Lyon in 353. Silvanus, one of his main commanders, who had defected to Constantius, was given the task of rebuilding defences in Gaul. However, being accused of plotting to become emperor, he decided to really make an attempt in 355 and was killed soon afterwards.[72]

A new phase of confrontation against the Suebian Alemanni in the west and Quadi in the east began under Constantius II (reigned 337-361). In 354, in the eastern regions of the Alemanni, he defeated the brothers Gundomadus and Vadomarius near Augst, and took the title Germanicus Alama(n)nicus maximus.[73] The future emperor Julian the Apostate was given responsibility for Gaul and the Rhine in 355 AD. Germanic peoples including Alamanni had settled within Gaul, and many parts of Gaul were suffering due to reduced cultivation of lands.

In the east in 357 Constantius II also fought the Suebian Quadi. The Quadi and their neighbours the Sarmatians were making raids across the Middle Danube into Roman Pannonia and Moesia. The account given by Ammianus Marcellinus shows that in this period the Quadi had become more accustomed to actions on horseback.[74] He reported that the involved Quadi and Sarmatians "were neighbours and had like customs and armour", "better fitted for brigandage than for open warfare, have very long spears and cuirasses made from smooth and polished pieces of horn, fastened like scales to linen shirts". They had "swift and obedient horses" and they generally had more than one, "to the end that an exchange may keep up the strength of their mounts and that their freshness may be renewed by alternate periods of rest".[75]

In 358 the emperor crossed the Danube and resistance quickly fell apart. The leaders who came to negotiate with the emperor represented different parts of the populations who had participated. An important one was prince Araharius, who ruled "a part of the Transiugitani and the Quadi". An inferior of his was Usafer, a prominent noble, who led "some of the Sarmatians". In the negotiations the emperor declared that the Sarmatians were Roman dependents and demanded hostages. He then learned that there had been social upheaval among the Sarmatians, and some of the nobility had even fled to other countries. He gave them a new king, Zizais, a young prince who was the first leader to surrender. He then met with Vitrodorus the son of Viduarius the King of the Quadi. They also gave hostages and they drew their swords "which they venerate as gods" in order to swear loyalty. As a next step he moved to the mouth of the Tisza and slaughtered or enslaved many of the Sarmatians who lived on the other side and had felt themselves protected by the river from the Romans.[76] King Viduarius was probably king of the western Quadi. Constantius erected a triumphal arch in Carnuntium, today known as the Heidentor, but raids did not stop.[77]

By 361, Julian captured a king of the Alamanni named Vadomarius, and claimed that he had been in league with Constantius II, encouraging him to raid the borders of Roman Raetia. Julian proceeded to send troops south and he became sole emperor in 361. He died in 363 AD.

Valentinian I (reigned 364-375) appears to have been preparing for campaigns against the Alemanni from an early phase.[78] The Roman usurper Procopius, declared himself emperor in Constantinople with the support of the Alemannic chieftain Agilo. Valentinian's military commander on the Rhine, Charietto, was killed in 366 fighting Alemanni who had penetrated deep into Gaul. Nevertheless the Alemanni were defeated just one month later at Châlons-sur-Marne, and Agilo and another chief named Gomoarius handed over the usurper Procopius to Valens, the younger brother and eastern co-emperor of Valentinian. In 368 other Alemannic chiefs, Vithicabius the son of Vadomarius, and Rando, provoked Valentinian with raids. Vithicabius was assassinated.[79]

Valentinian I built fortifications on the Rhine around 369/370.[80] He also fortified the northern and eastern banks of the Middle Danube against the Quadi and their allies, and by 373 AD he ordered construction of a garrisoned fort within Quadi territory itself. In 374, when complaints from the Quadi delayed construction the Roman general charged with getting it done invited their king Gabinius to dinner and then murdered him. As Ammianus wrote "the Quadi, who had long been quiet, were suddenly aroused to an outbreak". Neighbouring tribes including the Sarmatians sprung into action and began raids across the Danube, repulsing the Roman military's first poorly coordinated attempts to confront them.[81] Valentinian moved to the Danube border and went first to Carnuntum, which was damaged and deserted, and then Aquincum (now part of Budapest). He sent one force north into the Quadi heartlands, and took another force across the Danube near present-day Budapest, where the enemies had settlements, and they slaughtered everyone they could find. He then made his winter quarters on the Roman side of the Danube in Bregetio (present-day Komárom). Here Quadi envoys came to plead for peace. However, when they maintained that the building of a barrier was begun "unjustly and without due occasion", thus arousing rude spirits to anger, Valentinian became enraged, then sick, and died. His death in 375 ended this round of conflict, and the Romans and Quadi were soon preoccupied with bigger problems in the Danubian region.[82]

In 378 Valentinian's eldest son the emperor Gratian was occupied with a campaign against the Alemanni. He and his forces were therefore not present when the empire suffered a major defeat at the Battle of Adrianople, which was caused by a sudden movement of peoples including Goths, Alans and Huns coming from present-day Ukraine, which had been building up for some time. According to Ammianus, the region of the Marcomanni and Quadi were among the areas first affected by the "a savage horde of unknown peoples, driven from their abodes by sudden violence".[83] Armed groups began to settle in or near the Middle Danube, near the Quadi homeland.

After Adrianople and Late Antiquity

The defeat of the Romans at the Battle of Adrianople in 378 marked a turning point for the remaining Suebi on the Middle Danube frontier, including the Quadi and the Marcomanni. The arrival of large numbers of armed Huns, Goths and Alans disrupted the border region on both sides. At first the Suebi of the Middle Danube were to some extent drawn into alliances with the newcomers from the east. After the death of emperor Theodosius I in 395, Saint Jerome listed the Marcomanni and Quadi together with several of the eastern peoples causing devastation in the Roman provinces stretching from Constantinople to the Julian Alps, including Dalmatia, and all the provinces of Pannonia: "Goths and Sarmatians, Quadi and Alans, Huns and Vandals and Marcomanni".Castritius (2005) citing Jerome, Letters 60.16.2 f. The poet Claudian describes them crossing the frozen Danube with wagons, and then setting wagons rigged around themselves like a wall at the approach of the Roman commander Stilicho. He says that all the fertile lands between the Black Sea and Adriatic were subsequently like uninhabited deserts, specifically including Dalmatia and Pannonia. As in the past, many Suebi also entered the Roman Empire or moved further westwards towards the Alamanni and the Rhine, but this time they went further.

The Kingdom of the Suevi in Hispania

The last contemporary mention of the Quadi as an identifiable people is in another letter by Jerome from 409, but it places them far from home. He lists them first among the peoples who were occupying Gaul at that time: "Quadi, Vandals, Sarmatians, Alans, Gepids, Herules, Saxons, Burgundians, Allemanni and—alas! for the commonweal!—even Pannonians" (in other words Roman citizens from Pannonia).Kolník (2003, p. 636) citing Jerome, letter 123 to Ageruchia Scholars note that apart from the Saxons, Burgundians and Alemanni, who were already well-known near the Rhine, and the Alans who were newcomers from Ukraine who had already played an important role in the Roman military, the others appear to have been long-term neighbours from the Middle Danube area. Many of the Suebi in Gaul, probably including many Quadi, soon moved further west, into Hispania, where a large force of Suebi arrived by 409 AD, along with groups of Vandals and Alans.

Hispania was at this time under the control of the rebel Roman general Gerontius and the newcomers came to agreements with him as military allies in his struggle against Roman forces. The three groups proceeded to divide Hispania between themselves into four kingdoms, with the agreement of Gerontius. After the defeat of Gerontius, the Roman authorities rejected these agreements and the Visigoths began to work against the four kingdoms.[84][85] After many of the Vandals and Alans moved to Carthage, the Suebi were the last of them to hold an independent kingdom, which endured until 585, when it was absorbed by the Visigothic kingdom.

The Hunnic alternative

Some Danubian Suebi remained in the region which increasingly came under the control of the Huns, led at first by Uldin. A powerful Hunnic empire developed, giving the non-Roman peoples of the frontier an alternative way to improve their lives outside the empire. Herwig Wolfram has referred to this as the "Hunnic alternative".[86] This ended with the death of Attila in 453. In the ensuing period, a short-lived Kingdom of the Suevi emerged as one of several new ethnic kingdoms in Pannonia.

This kingdom was ruled by a man named Hunimund, and existed in or near north-eastern Pannonia. It may have been made up of Quadi, or a mixture of Suebians. After being defeated by the Ostrogoths, another of the successor kingdoms, Hunimund and some of his people seem to have moved west and joined the Alemanni, who had by now absorbed many Suebi, and eventually came to be called the Swabians.[87]

The Roman alternative

Other Middle Danubian Suebi moved southwards into Roman lands, including many Marcomanni. Ambrose, bishop of Milan (374–397), corresponded with a Christian Marcomannic queen named Fritigil, initiating a peace treaty between the Marcomanni and the western Roman military leader Stilicho. That was the last clear evidence of the Marcomanni having a polity, which was probably now on the Roman side of the Danube, in Pannonia. The Notitia Dignitatum lists several Marcomanni units among the surviving Roman military forces posted around the empire. The Ravenna Cosmography, a much later document which used sources that are in many cases now lost, indicates that a Marcannori people (Marcannorum gens) lived in the mountainous southwest of Pannonia near the Sava river. A Sava or Suavia province between the Sava and Drava rivers continued to exist during the time when the Ostrogoths ruled Italy, and may have been named after these Suebi (Suavi).

It is possible that the Suebi moved into this more southern area after the defeat of Hunimund, or they may have been a separate group. During the Ostrogothic period, these Suebi were legally distinguished from the native populations under the term "old barbarians" (antiqui barbari), which also distinguished them from the new arrivals, the Goths. Unusually, they were legally permitted to marry provincial residents and could therefore become part of the land-owning class. Some scholars believe these were descendants of the Christian Marcomanni of Queen Fritigil. During the time of Theoderic the Great a group of Alemanni crossed the Alps with cattle and wagons to seek refuge with these antiqui barbari. Procopius noted that in 537 the Ostrogoths recruited an army of these Suebi to launch an attack against areas held by the Eastern Roman empire. In 540 Ostrogothic rule in the Sava region came to an end, and the Suebi came under the authority of the Eastern Roman emperor Justinian.[88] Many of the Suebi who remained in the Pannonian region are believed to have taken up a Lombardic identity after the defeat of the Ostrogoths, and many may therefore have subsequently entered Italy with the Suebian Lombards.[89] The region subsequently came under the control of the Pannonian Avars, and it is probably during this period that Slavic languages eventually became dominant in the areas where the Quadi had lived.

Integration into the Lombards

Many Suebi from the Danubian region were assimilated into the Lombards, who had long been counted among the Suebian peoples in Roman ethnography. In the 6th century, Lombard expansion absorbed the Suebi of Suavia, and when the Lombards entered Italy after 568 these groups formed part of their realm. The survival of the Suebian name is reflected in the regional designation Lombardy.[89]

The Bavarians

The same text of Jordanes which mentions the Suebi joining the Alemanni is also one of the first records mentioning the early Bavarians, or Baiuvari. According to Jordanes the early Baiuvarii, were at this time living south of the Danube, to the east of the Alemanni, in what had been Roman territory.

The Baiuvari were not mentioned in the early 6th century biography of Severinus of Noricum describes the region in detail without mentioning them. The period when they first appear was soon after the defeat of the Rugii by Odoacer, who was at that time king of Italy. To the east of the Baivari, the power vacuum was filled the Suebian Langobards who moved from the Elbe in this period.[90]

Like the Swabians in Alamannia, in the Middle Ages the Bavarians and the Thuringians had their own stem duchies in the Holy Roman Empire.

Suebi who remained by the Elbe

Despite all these changes, another group of Suebi, the so-called "northern Suebi", seem to have survived near their Elbe homelands into the Middle Ages. They were described as a part of the Saxons in 569 under the Frankish king Sigebert I in areas of today's Saxony-Anhalt. An area known as Schwabengau or Suebengau existed at least until the 12th century.[85]

Norse mythology

The name of the Suebi also appears in Norse mythology and in early Scandinavian sources. The earliest attestation is the Proto-Norse name Swabaharjaz ("Suebian warrior") on the Rö runestone and in the place name Svogerslev.[91] Sváfa, whose name means "Suebian",[92] was a Valkyrie who appears in the eddic poem Helgakviða Hjörvarðssonar. The kingdom Sváfaland also appears in this poem and in the Þiðrekssaga.

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Harm, Volker (2013), ""Elbgermanisch", "Weser-Rhein-Germanisch" und die Grundlagen des Althochdeutschen", in Nielsen; Stiles (eds.), Unity and Diversity in West Germanic and the Emergence of English, German, Frisian and Dutch, North-Western European Language Evolution, vol. 66, pp. 79–99

- ^ Rübekeil 2005, pp. 184–185.

- ^ a b c d Rübekeil 2005, p. 186.

- ^ Sitzmann 2005, pp. 152–154.

- ^ Rübekeil 2005, p. 187.

- ^ Schrijver, Peter (2003). "The etymology of Welsh chwith and the semantics and morphology of PIE *k(w)sweibh-". In Russell, Paul (ed.). Yr Hen Iaith: Studies in Early Welsh. Aberystwyth: Celtic Studies Publications. ISBN 978-1-891271-10-6.

- ^ a b Florus, Lucius Annaeus. Epitome of Roman History. Book II section 30.

- ^ a b Dio, Lucius Claudius Cassius. "Dio's Rome". Project Gutenberg. Translated by Herbert Baldwin Foster. pp. Book 51 sections 21, 22.

- ^ a b Orosius, 6.21.15-16

- ^ a b Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius. "The Life of Augustus". The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Bill Thayer in LacusCurtius. pp. section 21.

- ^ Strabo, 4.3

- ^ Tacitus Germania Section 38

- ^ Scharf (2005), p. 191 citing Tacitus Germania Section 39

- ^ Tacitus, Germania, 1.42

- ^ a b Pohl (2004), p. 92, Scharf (2005), p. 193

- ^ Wolfram, Herwig (1999). "Germanic Tribes". Late Antiquity. Harvard University Press. p. 467. ISBN 9780674511736.

- ^ Castritius 2005, p. 193.

- ^ Castritius 2005, p. 194.

- ^ a b Robinson, Orrin (1992), Old English and its Closest Relatives pages 194–5.

- ^ Waldman & Mason, 2006, Encyclopedia of European Peoples, p. 784.

- ^ Maurer, Friedrich (1952) [1942]. Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien zur germanischen und frühdeutschen Sprachgeschichte, Stammes – und Volkskunde. Bern, München: A. Franke Verlag, Leo Lehnen Verlag.

- ^ Kossinna, Gustaf (1911). Die Herkunft der Germanen. Leipzig: Kabitsch.

- ^ Scharf 2005, p. 188.

- ^ Caesar, Gallic Wars, 4.1

- ^ Caesar, Gallic Wars, 4.1

- ^ Strabo, 7.1

- ^ Scharf (2005), p. 191 citing Tacitus, Germania, Section 38

- ^ Tacitus, Germania, Section 38

- ^ Scharf (2005), p. 188 citing Caesar, Gallic War, 1.37

- ^ Scharf (2005), p. 188 citing Caesar, Gallic War, 1.51

- ^ Caesar, Gallic War, 1.54

- ^ Caesar, Gallic War, 4.16

- ^ Caesar, Gallic War, 6.9

- ^ Schlegel 2002.

- ^ Steuer 2021, p. 1044.

- ^ Wiegels 2002.

- ^ Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius. "The Life of Tiberius". The Lives of the Twelve Caesars. Bill Thayer in LacusCurtius. pp. section 9.

- ^ Kehne (2001, p. 293) citing Monumentum Ancyranum 6

- ^ Tacitus, Annales, Book II section 26.

- ^ Hofeneder (2003, p. 625) citing Strabo, Geography 7.1.3

- ^ Hofeneder (2003, pp. 628–629) citing Velleius, 2.108

- ^ Velleius, 2.109

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, Compendium of Roman History 2.109; Cassius Dio, Roman History 55.28, 6–7

- ^ Kehne (2001, pp. 294–295) citing Tacitus Annals 2.45-46, 2.62-63, 3.11.1

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 2, 44-46

- ^ Tacitus Annals 2.63

- ^ a b Kehne 2001, p. 295.

- ^ a b Hofeneder 2003, p. 629.

- ^ Hofeneder (2003, pp. 628–629) citing Tacitus, The Annals 2.63, 12.29, 12.30.

- ^ Kehne (2001, p. 295) citing Tacitus, History, 3.5

- ^ Kehne (2001, p. 295). See Dio Cassius 67

- ^ Tacitus, Germania, 42

- ^ Kehne (2001b, p. 310) citing Dio Cassius 72.3

- ^ Kehne 2001b, pp. 310–311.

- ^ a b c Kehne 2001b, pp. 311–312.

- ^ a b c Kolník 2003, p. 633.

- ^ Kehne 2001b, p. 314.

- ^ Kehne 2001b, p. 313.

- ^ Kolník 2003, pp. 633–634.

- ^ Kehne 2001, p. 298.

- ^ Tejral 2001, p. 305.

- ^ Kolník (2003, p. 634) citing Dio Cassius, Roman History, 78

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 657, Hummer 1998, p. 6

- ^ Steuer 2021, p. 1078.

- ^ Kehne (2001, p. 299) citing Zosimus 1.29

- ^ a b Kehne 2001, p. 299.

- ^ a b Kolník 2003, p. 634.

- ^ Runde 1998, pp. 658–659.

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 661, Nixon & Rodgers 1994, pp. 61–62

- ^ Nixon & Rodgers 1994, pp. 100–101, 541.

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 662.

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 665.

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 666.

- ^ Kolník (2003, p. 635) citing Ammianus, History, 17

- ^ Ammianus, History, 17

- ^ Ammianus, History, 17

- ^ Kolník 2003, p. 635.

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 669.

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 670.

- ^ Runde 1998, p. 671.

- ^ Kolník (2003, p. 635) citing Ammianus 29.6

- ^ Kolník (2003, p. 636) citing Ammianus 30.6

- ^ Ammianus 31.4

- ^ Castritius 2005.

- ^ a b Reynolds 1957.

- ^ Wolfram 1997.

- ^ Castritius 2005, p. 195.

- ^ Castritius 2005, pp. 196–201.

- ^ a b Castritius 2005, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Goffart 2010, p. 219.

- ^ Peterson, Lena. "Swābaharjaz" (PDF). Lexikon över urnordiska personnamn. Institutet för språk och folkminnen, Sweden. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-05-18. Retrieved 2007-10-11. (Text in Swedish); for an alternative meaning, as "free, independent" see Room, Adrian (2006). "Swabia, Sweden". Placenames of the World: Origins and Meanings of the Names for 6,600 Countries, Cities, Territories, Natural Features and Historic Sites: Second Edition. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. pp. 363, 364. ISBN 0786422483.; compare Suiones

- ^ Peterson, Lena. (2002). Nordiskt runnamnslexikon, at Institutet för språk och folkminnen, Sweden. Archived October 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

General sources

- Ferreiro, Alberto. "Braga and Tours: Some Observations on Gregory's De virtutibus sancti Martini." Journal of Early Christian Studies. 3 (1995), p. 195–210.

- Castritius, Helmut (2005), "Sweben § 8-13", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 30 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018385-6

- Hofeneder, Andreas (2003), "Quaden § 2. Historisches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 23 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-017535-6

- Hummer, Hans (1998), "The fluidity of barbarian identity: the ethnogenesis of Alemanni and Suebi, AD 200-500", Early Medieval Europe, 7 (1): 1–27, doi:10.1111/1468-0254.00016

- Kehne, Peter (2001), "Markomannen § 1. Historisches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 19 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-017163-1

- Kehne, Peter (2001b), "Markomannenkrieg § 1. Historisches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 19 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-017163-1

- Kolník, Titus (2003), "Quaden § 3. Historische Angaben und archäologischer Hintergrund", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 23 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-017535-6

- Goffart, Walter (2010). Barbarian Tides: The Migration Age and the Later Roman Empire. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812200287.

- Nixon, C E V; Rodgers, Barbara Saylor (1994). In praise of later Roman emperors: the Panegyrici Latini. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08326-1.

- Pohl, Walter (2004), Die Germanen, Enzyklopädie deutscher Geschichte, vol. 57, ISBN 978-3-486-70162-3, archived from the original on 23 April 2023, retrieved 30 March 2020

- Reynolds, Robert (1957), "Reconsideration of the history of the Suevi", Revue Belge de Philologie et d'Histoire, 35: 19–45

- Rübekeil, Ludwig (2005), "Sweben § 1. De Name", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 30 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018385-6

- Runde, Ingo (1998). "Die Franken und Alemannen vor 500. Ein chronologischer Überblick". In Geuenich, Dieter (ed.). Die Franken und die Alemannen bis zur "Schlacht bei Zülpich" (496/97). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde – Ergänzungsbände. Vol. 19. De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-015826-7.

- Scharf, Ralf (2005), "Sweben § 2-7", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 30 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018385-6

- Schlegel, Oliver (2002), "Neckarsweben § 2. Archäologisches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 21 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, pp. 45–47, ISBN 978-3-11-017272-0

- Sitzmann, Alexander (2005), "Semnonen § 1. Namenkundlich", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 28 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018207-1

- Steuer, Heiko (2021). Germanen aus Sicht der Archäologie: Neue Thesen zu einem alten Thema. de Gruyter.

- Tejral, Jaroslav (2001), "Markomannen § 2. Archäologisches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 19 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-017163-1

- Thompson, E. A. "The Conversion of the Spanish Suevi to Catholicism." Visigothic Spain: New Approaches. ed. Edward James. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1980. ISBN 0-19-822543-1.

- Wiegels, Rainer (2002), "Neckarsweben § 1. Historisches", in Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.), Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde, vol. 21 (2 ed.), De Gruyter, pp. 39–45, ISBN 978-3-11-017272-0

- Wolfram, Herwig (1997). The Roman Empire and Its Germanic Peoples. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520085114. Archived from the original on 2023-04-23. Retrieved 2020-01-26.

External links

- The Chronicle of Hydatius is the main source for the history of the Suebi in Galicia and Portugal up to 468.

- Identity and Interaction: the Suevi and the Hispano-Romans, University of Virginia, 2007

- Medieval Galician anthroponomy

- Minutes of the Councils of Braga and Toledo, in the Collectio Hispana Gallica Augustodunensis

- Orosius' Historiarum Adversum Paganos Libri VII