Suquamish people

suq̓ʷabš | |

|---|---|

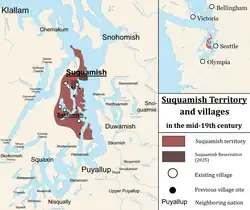

Suquamish territory in the mid-19th century | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Washington (United States) | |

| Languages | |

| English; historically Lushootseed | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional ethnic religion; Christianity (incl. syncretic forms) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Southern Coast Salish peoples, notably the Duwamish and Twana |

The Suquamish people (soo-KWAH-mish; Lushootseed: suq̓ʷabš /ˈsoqʼʷɑbʃ/) are a Southern Coast Salish people Indigenous to western Washington state. Historically, the Suquamish dominated much of northeastern Kitsap Peninsula, with their main village, dxʷsəq̓ʷəb, being located at what is today Suquamish, Washington. They are politically succeeded by the Suquamish Indian Tribe, a federally recognized Native American tribe that governs the Port Madison Indian Reservation.

The Suquamish were deeply affected by both smallpox epidemics and raids from more northern Indigenous peoples like the Cowichan and Lekwiltok in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the early 19th century, they were led by Kitsap, who met with George Vancouver's expedition in 1792. Around 1825, Kitsap led the Suquamish and other Indigenous peoples from Puget Sound in a region-spanning coalition against the Cowichan, who had long been targeting the region with slave raids, ultimately losing the battle but ending Cowichan raids in the future. After Kitsap's death, Challacum became the preeminent leader of the Suquamish, who continued Kitsap's policy of friendliness with European traders. Seattle led the Suquamish and Klallam in a major raid against the neighboring Chemakum, killing most of them. He would later become the leader of the Suquamish after Challacum, and was recognized as head chief of the Suquamish and other tribes during the treaty process of the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855.

The Point Elliott treaty created the Port Madison reservation in their territory, on which the Suquamish continued to live. During this period, they faced cultural repression from the policies of assimilation of the United States government and changes in the traditional culture and social organization. Traditional Suquamish life was dominated by seasonal cycles of fishing, hunting and gathering, based from permanent winter villages. They maintained close ties with groups such as the Twana and Duwamish as they travelled to summer grounds, but fishing and canning industries in the 20th century threatened this lifestyle. In the 1960s, the Suquamish organized into the modern Suquamish Indian Tribe, which continues Suquamish political sovereignty today.

Name

The name "Suquamish" is from suq̓ʷabš, the name for the Suquamish people in their language, Lushootseed.[1] The name is from the root √suq̓ʷ and the suffix =abš, 'people'.[1]

The name suq̓ʷabš is often translated to mean "people of the clear saltwater".[2][3] This translation derives from dxʷsəq̓ʷəb (variously xʷsəq̓ʷəb),[4] the name for the site of the main Suquamish village on Agate Pass.[3] According to early-20th-century anthropologist T. T. Waterman (who recorded many place names around Puget Sound between 1918 and 1920),[5] the meaning of the name probably arose from the contrast of the slow-moving and turbid water of Liberty Bay as compared to the swift-moving and clear tide water flowing through Agate Pass.[6]

This is most likely a folk etymology according to anthropologists and linguists Nile R. Thompson and William W. Elmendorf.[3] Elmendorf instead posited a Twana-language origin for the name suq̓ʷabš.[7] According to Elmendorf's Twana informants, the name came from the Twana word wuq̓ʷatəb, 'drifted away' (cf. Twana swuq̓ʷabəš 'Suquamish'). They believed that most Suquamish were unaware of the Twana etymology of their name, since the word for drift in Lushootseed is p̓əq̓ʷ.[8][1] Additionally, Thompson noted that in Twana oral history, there is a story about how after a great flood, the ancestors of the Suquamish drifted away eastward to their homeland on Agate Pass, which he argued supports the Twana origin theory.[9]

The Suquamish have also been called ʔitakʷbixʷ, 'mixed people' (anglicized as Itakmahu[10] or Etakmur[11]) by other groups such as the Snohomish.[12][2][13] This name could have referred to the Suquamish as having many connections, or it could have been a derogatory nickname questioning the ancestry of the noble families of the Suquamish.[11]

The English name "Suquamish" in the past has been spelled variously as Soquamish,[14] Soquam,[15] Swuwkwabsh, and Suqabsh.[16]

Classification

The Suquamish are a Southern Coast Salish people.[17] Coast Salish refers to a grouping of Indigenous peoples on the Pacific Northwest Coast who are speakers of the Coast Salish languages. The entirety of the Coast Salish region was connected by a socio-economic network of cooperation, intermarriage, and trade, between the Coast Salish peoples, which created a social continuum across the region. Although they have similar cultural backgrounds, there are differences within the traditional cultures and post-contact histories within the region that can be used to create subregions within the broader Coast Salish world. Anthropologist Wayne Suttles divided the Coast Salish nations into four subregions based on these differences.[18] The Southern Coast Salish subregion includes the Twana and the many Lushootseed-speaking nations of Puget Sound.[17]

Subgroups

Other groups have been identified as subgroups of the Suquamish. The Saktamish (Lushootseed: sx̌aq̓tabš; transliterated variously as Saktamish, Shaktabsh or S'haktabsh) occupied Dye's Inlet and Sinclair Inlet.[16][10] These people were an extended settlement of Suquamish people; a poor, low-class group that lacked any high-class families. They were looked down upon by their neighbors, who described them as "poor people" and "not good for much".[19]

Early-20th-century ethnographer Edward Curtis associated the S'Homamish (sx̌ʷəbabš)[20] with the Suquamish as well.[16] However, other sources identify the S'Homamish with the Puyallup.[21][22][8] Specifically, anthropologist Marian W. Smith noted that the S'Homamish were closely affilated with the Puyallup. According to their oral history, their original village at Gig Harbor (txʷaalqəɬ)[20] was founded by an offshoot group of the Puyallup.[22]

Geography

Historic territory

The core of the historic territory of the Suquamish is northern Kitsap Peninsula.[3] In 1855, the Suquamish held the west side of Puget Sound from the mouth of Hood Canal to Olalla and Vashon Island, including Port Madison, Liberty Bay, Port Orchard, Dye's Inlet, and Sinclair Inlet. They also held Bainbridge Island and Blake Island.[14] They were bounded by the Twana to the west on Hood Canal, the Chemakum to the north, the Duwamish to the east, and the Puyallup to the south.[23]

Some descriptions of the Suquamish land base have included the western parts of Whidbey Island. There is no clear evidence of any Suquamish winter villages on Whidbey Island, so references to Suquamish habitation of the island may be referring to seasonal occupation for fishing, hunting, and gathering, rather than permanent occupation.[24] One Skokomish informant mentioned that the village at Port Gamble was originally Suquamish, but by the time of the treaty, it was primarily occupied by the Chemakum and Klallam.[25][26] Suquamish people recalled in the late 20th century that previous generations seasonally utilized sites on Hood Canal as well.[23]

One 1930 ethnographic report stated that the Suquamish also occupied the eastern shore of Puget Sound from Mukilteo south to Seattle.[27] However, other sources do not include this area as Suquamish territory.[23][21]

Historic village sites

According to anthropologist Barbara Lane, by the mid-19th century, the Suquamish resided in six winter villages: at Suquamish, Poulsbo, Chico Creek, Phinney Bay, and Colby.[28] Other villages existed before the mid-19th century, and some seasonal sites became permanent settlements after white contact.[29] At the site of the modern-day town of Suquamish on Agate Pass, there was the village of dxʷsəq̓ʷəb. This village was home to the famous Old Man House, a 520 feet (160 m)[30][31] by 60 feet (18 m) shed-roof longhouse that was the center of Suquamish cultural and political life. Old Man House accommodated several families.[2] Notable Suquamish figures such as Kitsap, Schweabe, Challacum, and Seattle, after whom the city was named, lived in this house.[11][30] Another village was located just south of Agate Pass on Sandy Hook (ʔəshudič, 'burned over'); this village had several small shed-roof longhouses.[30][32]

One village was located at the head of Liberty Bay, near what is today Poulsbo.[28][21][33][34] This village had one shed-roof house in which several families lived. The area was good for salmon fishing and deer hunting, as well as gathering mushrooms.[34] Snyder, who recorded place names in 1952, also noted that a Suquamish family had lived in the past at dəxʷp̓əc̓p̓əc̓əb (lit. 'place of diarrhea'), east of what is today Lemolo. The people in this village were called sqaqabixʷ, 'many people'.[34] A fort was located south of this spot at Keyport Lagoon (hudčupali, 'firewood place'), built to defend against raids from tribes to the north.[34]

On Dye's Inlet, there was a village at Chico Creek. This village had one shed-roof house, but Synder's Suquamish informants did not remember whether it was built before or after settlers came to Puget Sound.[35] Nearby, on Erland's Point, there was a large gable-roof longhouse that was built around 1880 and was possibly the last-standing Suquamish longhouse.[36] Barbara Lane also wrote that there was a village on Phinney Bay as well.[28]

Another village was located at bək̓ʷaʔkʷbixʷ, present day Colby.[28] This village was described as "ancient." The name means "people from different places gathered together", literally "all people".[37] Only the frames of the houses here were remaining by the mid-19th century.[38] The southernmost place occupied regularly by the Suquamish was the area around Ollala Creek. Charles Wilkes, who visited the area in 1841, noted that there was a village at this creek, but later it was only remembered by Suquamish informants to be a temporary camping ground.[38]

Villages were also located on Bainbridge Island. An old village was located at Snag Point, which had a fort like the one at hudčupali.[39][40] Another village recorded by Waterman was at Point White[28] (dəxʷʔəx̌adəč; reportedly meaning 'goose droppings').[41][a] Waterman reported an "ancient village" on the west side of Port Madison Bay, near West Port Madison, noting that Kitsap lived there at one point.[42] Smith (1940) reported winter villages at Point Monroe on Hedley Spit and Eagle Harbor.[12] However, Snyder (1968) disagreed that these was originally anything other than campsites, noting that although there were shacks there, Synder's Suquamish informants only remembered them as places of seasonal occupation before white settlement.[29] A number of Duwamish people were made to move to Hedley Spit by the federal government in 1856, because they mistakenly believed that the Duwamish were a part of the Suquamish because Seattle was assigned to be their treaty signer. However, most of the Duwamish left this spot soon after.[30]

Port Madison reservation

The primary land base of the Suquamish people today is the Port Madison Indian Reservation, governed by the Suquamish Indian Tribe. Established on Suquamish lands in 1855, it was one of four reservations created by the Treaty of Point Elliott.[43] Today, around two hundred tribal members lived on the reservation in 2010 (out of a population of 950 tribal citizens at the time). Many tribal members live in nearby communities, such as Sequim, Bremerton, Port Orchard, Seattle, and Tacoma, as well.[44]

History

Kitsap's leadership

After the societal instability created by smallpox epidemics, the Northwest Coast was marked by a period of violence and conflict.[45] The Suquamish and the Chemakum fought back and forth: the Suquamish accused the Chemakum of encroaching on their lands. Schweabe, a high-ranking Suquamish and Chief Seattle's father, also led raids against the Twana and the Duwamish.[46][44] Northern tribes who were affected by the epidemics began raiding the peoples of Puget Sound for slaves and loot to bolster their diminished populations and economies.[47]

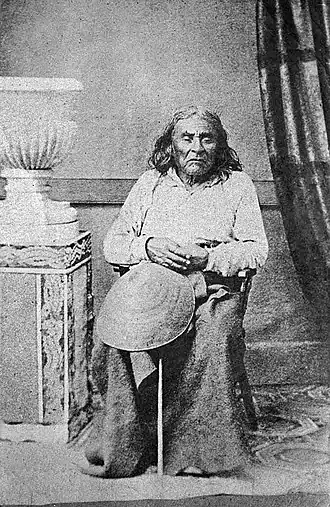

Seattle, who became the most well-known Suquamish leader, was born around 1786 on Blake Island (Lushootseed: tatču).[48][44]

The Suquamish met George Vancouver in 1792 when he was surveying Admiralty Inlet. He visited a summer camp at the southern point of Bainbridge Island, noting the population at the time to be around 80-100.[49] After a dinner was hosted for Vancouver at the camp, two Suquamish men boarded Vancouver's ship, the Discovery, and traded with the sailors. One of the men was probably the famous leader Kitsap (who was also Seattle's uncle).[50]

The Old Man House at dxʷsəq̓ʷəb was built by Kitsap around the early 19th century. According to tradition, Kitsap saw the house in a dream where the Suquamish had a massive building to greet the Europeans when they returned to Puget Sound.[31] Over the next four years, the house was built by clearing and excavating a swamp, felling cedars and crafting them into the posts and rafters, then workers from tribes across western Washington were invited to compete to raise the giant timbers.[31] Historian David Buerge wrote that some of the petroglyphs on Figurehead Rock (x̌alilc)[51] may have related to the building of this house, noting that Kitsap was remembered to have carved some during his life.[11]

Attack against the Cowichans

By the 1820s, the Suquamish were noted by traders to be wary, hiding from visitors and reluctant to engage in trade. They had been the target of raiders from the north; one of the most feared groups were the Cowichans of Vancouver Island. The Cowichans had been raiding the Fraser River, the Strait of Georgia, and Puget Sound, seeking to corner the market and force the Hudson's Bay Company traders to come to them. When an HBC trade expedition from the south came up Puget Sound, they intended to trade with the a Suquamish chief, probably Kitsap. However, when they came to Suquamish, they found the villages largely abandoned and the few remaining saying that the rest had "gone fishing" in the woods. One of the tactics of surviving raids was simply hiding from the attackers, and with the approach of the unfamiliar and armed HBC traders, the Suquamish may have thought they were under attack.[52]

Kitsap sought to put an end to this and to re-open Puget Sound to traders. Kitsap organized a coalition of tribes from across the region, coming from as far south as the Columbia River and centered on Old Man House.[53] Around 1825, the coalition, led by Kitsap and the Suquamish, set north to attack the Cowichan. The Suquamish were joined by the Stkamish, the Sammamish, and other warriors from the Puyallup and Nisqually, the Squaxins, and even from the Upper Chehalis and the Cowlitz. More than two hundred canoes set out north, pillaging Snohomish and Skagit camps on Whidbey Island as they went. They crossed the San Juans and Haro Strait to Vancouver Island, where they arrived at a Sooke village near Victoria. They looted and took prisoners from the village, and the headman told them that the Cowichan and the Saanich were off raiding Klallam villages on the Olympic Peninsula. However, as the Puget Sound coalition set off to find the Cowichan forces, they were met by the Cowichan and Saanich returning from their raiding. The Cowichan forces attempted to parley, but the Puget Sound force began combat, slaughtering the Sooke prisoners and throwing them overboard. The Cowichan and Saanich canoes feigned retreat, drawing in the Puget Sound canoes. After the Cowichan forces had separated the coalition forces into smaller groups, they rammed their canoes into the smaller Puget Sound canoes, stabbing those that fell overboard with spears. The Puget Sound force soon fell into retreat, fleeing into the open waters; only forty canoes returned from the assault. Although they lost the battle, it convinced the Cowichans to stop raiding south.[54] Furthermore, the Suquamish and Cowichan would maintain friendly relations and marriage ties thereafter. When Kitsap's son came to Fort Langley to trade, he was given protection by the Cowichan, and many Suquamish would marry into Cowichan families: Seattle's sister married a Cowichan, as did his daughter, Angeline.[55]

After the war with the Cowichans, the Suquamish began to cement ties to European traders. When a Hudson's Bay Company expedition came again to Puget Sound, the Suquamish were waiting with gifts and trade goods for the traders upon their arrival.[55] In 1828, A Klallam party attacked an HBC mail convoy. According to the Klallam, it was "a matter of honor", but the HBC believed it was only for loot and wanted to retaliate.[56] When the Suquamish heard about the retaliatory expedition, they offered to join the HBC against the Klallam, as they had traded goods to the murdered traders, then taken by the Klallam. Four Suquamish canoes followed the HBC schooner Cadboro commanded by chief trader Alexander McLeod as it moved against the Klallam. The Klallam sent word in an attempt to parley, but in the morning, McLeod's men opened fire on a village at Port Hadlock, killing eight men, women, and children. They then sailed west to the village at Dungeness, ignoring an attempt to facilitate a parley by Washkalagda, the neutral Snohomish headman from southern Whidbey Island. The Cadboro arrived at the Dungeness village, opening fire on it with their cannons, killing twenty-seven, and looting the place. They then returned to Port Townsend and burned the longhouse on their way back.[57]

Sometime before the 1830s, and possibly after the 1828 Hudson's Bay Company expedition,[58] Kitsap died.[59] According to his grandson William, he was murdered. His bones would later be stolen by grave-robbers from the Smithsonian Institution.[59] After his death, the Suquamish would continue his policy of friendliness with European traders.[58]

Challacum's leadership

Kitsap was succeeded by Challacum. Challacum was born to a Suquamish father and a Skagit mother who was related to a noble Skagit family, possibly the family of their chief Sneatlum. He was also noted by HBC surgeon William Fraser Tolmie to be "well disposed towards the whites" as was Kitsap.[60]

Challacum and the Suquamish would continue to aid the Hudson's Bay Company in their trade and settlement of the region, assisting them in both defense from and negotiations with neighboring groups.[61] In the summer of 1833, the Suquamish nearly had a conflict with the HBC after Tolmie misinterpreted a letter of warning from Challacum. Challacum had meant to warn Tolmie of an incoming Klallam attack, however Tolmie thought Challacum was threatening the HBC. When Tolmie confronted Challacum and other Suquamish leaders such as Seattle, Challacum was humiliated and furious, going on a tirade against Tolmie. Challacum then threatened to actually attack the HBC, and both the HBC and the Suquamish prepared for war, with the HBC building palisades in Suquamish territory, again taken as an affront to Suquamish sovereignty. Ultimately, Tolmie attempted to calm the situtation by offering gifts to Challacum, and tensions would settle by the fall.[62] The Suquamish would later trade with the Hudson's Bay Company at Fort Nisqually, which would be established in 1833.[44] They also came under the influence of Catholic missionaries in the 1830s and 1840s,[44] Challacum acting as a translator for sermons.[63]

In 1838, Seattle murdered a Skykomish doctor. Tensions again were raised between the HBC, the Suquamish, and the Skykomish. Furthermore, the murder weapon was a gun that came from the Sahewamish, so they were deemed involved as well. The HBC wanted Seattle killed in retaliation, but the Skykomish relatives of the murdered only wanted a weregild. Challacum negotiated on behalf of the Suquamish and Sahewamish, settling the matter.[64]

Challacum was last mentioned in the historical record in 1848.[65] After Challacum's leadership, Seattle became the pre-eminent leader among the Suquamish. Another high-ranking leader at this point was a man named Wilak, who was described at points as a head chief and subchief, and possibly served as an interpreter at the treaty in 1855.[66]

_(14595204268).jpg)

Attack against the Chemakum

After a Suquamish shaman was murdered by the Klallam, Seattle led the Suquamish in a revenge raid. Peace was made between the two parties when Seattle arranged his son Sakwal to be wed to the daughter of a Klallam leader. The two groups also agreed to work together to conduct a raid on the neighboring Chemakum people. The Suquamish and Chemakum both had their grievances with each other. The Chemakum blamed the Suquamish for a decline in the fertility of their lands, while the Suquamish were upset that the Chemakum were encroaching on their territories. Moreover, when the shaman was murdered, his head had been kept as a trophy and defiled by the son of the assassin, who was half Chemakum.[67]

Previously, the Chemakum had been devastated by a Makah raid and remained fortified in one stockaded village at Hadlock. Over one hundred warriors from the Suquamish, Klallam, and Duwamish came in fifteen canoes to the last Chemakum village. The warriors hid in the forest, waiting in a circle around the village, keeping close enough to touch one another. Early in the morning, a Chemakum man walked out of the village to go clamming. The warriors shot him, awakening the village and beginning the attack. As Chemakum warriors grabbed their muskets and ran outside, they were shot down, and the attacking force rushed inside the village. The attackers killed the men and took the women and children hostage. Near the end of the battle, a Chemakum man shot Sakwal, shattering his backbone. As he crumpled down, Seattle cried, "Oh! My son! My son! He is down!"[67] While Seattle is usually credited with organizing the raid, one account stated that Sakwal was the one who led the attack itself. Sakwal had also been involved in an earlier raid, during which he shot and killed a man. The Chemakum found the musketball lodged into a wall, hammered it into shape, and kept it, vowing to one day return it. It was this ball that a Chemakum man loaded into his rifle, fatally shooting the son of Seattle.[67]

Virtually all the Chemakum were killed in this attack. The headman of the Chemakum village and a few others managed to survive or flee, taking up residence with the Twana at Hood Canal. A few other survivors moved to Port Townsend.[68]

Treaty of Point Elliott

By the mid-19th century, there were about 500 Suquamish people. In 1844, they were listed to have a population of 520 people.[44] An estimate made in January 1854 counted approximately 485 Suquamish in the general area, based on information from settlers residing in the vicinity.[69]

On January 22, 1855, the Suquamish were party to the Treaty of Point Elliott, alongside a number of other groups in the region. They were named in the preamble of the treaty and seven people were designated as signatories for the Suquamish. Seattle was designated by the treaty commission as the head chief of the Suquamish as well as of the Duwamish and the "allied tribes".[70] By this time, he was no longer known for being a war leader, but as an ally of the Americans and a honorable leader who followed the wishes of the people. It was for these reasons both the Suquamish and Americans recognized his position of leadership among the Suquamish[71]. Seattle and his sons produced a list of twenty-two leaders from Suquamish and Duwamish villages for the commission to choose sub-chiefs from.[72] Six Suquamish individuals were designated as sub-chiefs for the purposes of the treaty.[70][44]

- Seattle (siʔaɬ)

- Chulwiltan (čul̕xʷiltən)

- Mislotche (wahəƛ̕čuʔ, a.k.a. Wahehltchoo )

- Sloonokshtan (sɬunukʷštən, a.k.a. Jim)

- Moowhahladhu (muxʷaladxʷ, a.k.a. Jack)

- Toolehplan (tuliplən)

- Hooviltmehtum (hučiltməʔ)

Article 2 of the treaty stipulated for the creation of a reservation at "Noo-sohk-um", or Port Madison,[74] which was primarily intended for the Suquamish and Duwamish people.[43] Originally, the reservation was planned to be for the Suquamish as well as the Klallam and Duwamish, and was located on Hood Canal, but the plans changed before the day of the treaty.[76]

Most Suquamish removed to the reservation, as it was located in their territory.[43] An 1856 estimate by George A. Paige, the Indian Agent in charge of Fort Kitsap, counted roughly 441 Suquamish living on the newly-created reservation. This tally included 117 free adult[b] males, 91 free male children, 102 free adult females, 97 free female children, as well as enslaved individuals: 8 enslaved adult males, 6 enslaved male children, 12 enslaved adult females, and 8 enslaved female children. In addition, Paige noted around 40 people in six families who were living in the vicinity of Port Orchard who had resisted removal. Together, the total was around 480 Suquamish in 1856.[69]

The Suquamish were prevented by the U.S. government from travelling during the Puget Sound War of 1855-1856. They could not travel to the rivers where they would normally have acquired large quantities of salmon, thus starvation became a large problem. In December of 1856, the Suquamish came to the reservation en masse in an attempt to find provisions.[77]

Reservation era

Seattle lived on the new Port Madison reservation, was associated with the Suquamish, and was recognized as their leader until his death in 1866.[70] After his death, his son Jim Seattle acted as chief. His recognition as leader quickly faded, as he "talked rough to the people" and was described as being "quick tempered and easily offended."[78] In the place of Jim Seattle, the Suquamish selected Jacob Wahelchu (also spelled Worheltchoo) to act as chief. Wahelchu was a Catholic as was Seattle, but was more opposed to the traditional religion. The Catholic faction among the Suquamish were empowered, and traditional religious ceremonies were forbidden.[78] Wahelchu was also likely a relative of the wahəƛ̕čuʔ who signed the treaty in 1855. This surname would continue to be associated with the Suquamish community at Port Madison until around 1910, when descendants dropped Wah-hehl-tchoo and changed the name to Jacob or Jacobs.[79]

Even after the Suquamish were confined to the reservation, encroachments from northern tribes continued in the region. In 1859, a Suquamish war party attacked a group of Haida on the western shore of Bainbridge Island in retaliation for previous Haida raiding on Puget Sound.[44]

Despite reservation bans on alcohol, whiskey sellers continued to attempt to sell alcohol. In 1862, Suquamish leaders seized and burned a boat belonging to rum dealers during a gathering of Suquamish and Duwamish people at Port Madison.[80]

The reservation was initially two sections of land (2 square miles, 5.2 km2) but it was repeatedly increased in size, eventually to 11 square miles (28 km2) between 1863 and 1873 after Seattle and other leaders petitioned in the territorial capital of Olympia.[81] In the 1870s, the Old Man House was burned down by the federal government, a destruction of the physical and spiritual center of the Suquamish community.[2]

By 1885, a large decrease in the population of the Port Madison Reservation was noted, either due to a reduction in the Suquamish population, or simply a decrease in the reservation population. The census of 1885 recorded an on-reservation population of 142. By 1910, the population grew to 181. Census rolls of the Suquamish Tribe in 1942 show 169 enrolled members, while 1953 rolls show 183 enrolled members, 1⁄3 of whom were children.[82] In 1985, the population increased to 577.[44] In 2011, there were 1,050 enrolled members.[83] These figures do not include individuals of Suquamish descent who are enrolled in other tribes.

Many Suquamish at this time were working at mills along the coast. One mill at Port Madison paid the Suquamish working there only in square-inch brass pieces which could be exchanged for food at stores.[84]

20th century

Suquamish people gained some compensation for their lands via the Indian Claims Commission, and the tribe was paid $36,329.51 for ceding their land in the Treaty of Point Elliott.[85] Following the passage of the Indian Reorganization Act in 1934, the Suquamish worked towards building their political sovereignty and a government-to-government relationship with the federal government. In 1956, the Suquamish Indian Tribe was formed by the Suquamish (along with some Duwamish) on the Port Madison reservation, adopting a formal constitution and establishing the governance still extant today.[86][87]

Traditional culture

Language

The original language of the Suquamish people is Lushootseed, a Coast Salish language originally spoken on Puget Sound from the Cascades to Kitsap Peninsula.[87] The dialect spoken by the Suquamish is Southern Lushootseed.[88]

Due to the American government's attempts to assimilate the Suquamish people, the language declined over the 19th and 20th centuries, almost to the point of total loss. Despite this, the Suquamish Tribe is involved in revitalizing the language. The tribe has a Traditional Language Program that teaches Lushootseed to schoolchildren as well as community members.[87]

Potlatch

The most important ceremony historically, and still a vital part of traditional culture, is the potlatch (Lushootseed: sgʷigʷi). Historically, the potlatch was a special celebration in which the host invited people from all over the region to give away his or her possessions to the guests. The host would spend years amassing property for the purpose of giving it away, as the value of gifts given determined the relationships between individuals and the prestige within their community. Potlatches were originally held for multiple reasons, including to celebrate childbirth, the coming-of-age of a daughter, marriage, naming ceremonies, or to assuage debts or injuries made to a person.[89]

Traditionally, a potlatch could last several weeks. The event would begin with the arrival of the guests. Each party would arrive in a big canoe, advancing in a line, covered in eagle down and singing. Sometimes, the host's people would ceremonially block the advance of the incoming party, in which the visitors had to engage in a shoving match to prove their honor. As the feast began, orators would speak, welcoming people, giving thanks, and reciting the lineages of the attendees. Throughout the feasting, gambling games and dances were held as well.[90] To conclude the celebrations, the host would sing their power song, and a master of ceremony would call up guests one-by-one to receive their gifts.[91]

Secret society

The higher-ranking Suquamish had what is often described as the "secret society". This society, which was often called "black tamanawis" or "growling", was obtained from the Nitinaht and Makah through intermarriage with the Klallam, and was only definitively practiced among the Twana and Suquamish, not by other Southern Coast Salish peoples. Though described as a society, members did not organize unless initiating new members. It could only be joined if sponsored by a member.[92][93]

The initiation ceremony most often happened during wintertime. During the initiation, the initiate would be carried off deep into the forest. The ceremony included regular spirit dancing until the initiate would be posessed through religious power. The initiate would fall into a trance, and after one or more nights of dancing and performances, they were awoken with blood being spat onto them. Following this, the initiate ran off into the woods, and they had to be restrained with ropes so as they would not bite the onlookers. After the initiation, they were reintegrated to normal society, and the hosts distributed gifts to the guests and paid the initators.[92] These initiation ceremonies were sometimes part of the potlatch ceremonials as well. Seattle himself was a member, and he hosted an initiation potlatch on Elliott Bay in 1850.[93]

Traditional foodways

Salmon was historically the staple food of the Suquamish. Other fish, such as cod, flounder, perch, trout, herring, and smelt were also part of the traditional diet.[86] Types of shellfish, including clams, oysters, crabs, and shrimp were also important.[86] Their territory did not have any large rivers; it was marked by many bays and inlets into which small streams and lakes flow, providing areas for freshwater fishing.[94] Spring, silver, and dog salmon were all taken in these small creeks.[95] Dog salmon were caught in Ross Creek, Chico Creek, and Blackjack Creek during their fall runs. Steelhead were speared in the Union River and Curley Creek.[95][36]

In the saltwater, springs were trolled for at Apple Cove Point and Hood Canal. Silvers were commonly taken at Apple Cove Point, Dye's Inlet, Liberty Bay, and Sinclair Inlet, as well as at Skunk Bay at the northern end of Kitsap Peninsula.[95] The saltwater expanse provided a year-round source of seafood, primarily fresh fish and shellfish, but to acquire the great quantities of smoked salmon that accounted for a major portion of the winter foodstores, the Suquamish travelled to rivers in the territory of their relations, such as the Duwamish and Snohomish, to participate in harvesting the fall salmon runs.[94] Fishing continued to be a large part of the Suquamish economy and lifestyle after colonization.[96] By 1920, non-Indigenous fishing and canning businesses had begun threatening fish runs in Suquamish waters, as well as across Puget Sound.[84]

Hunting was a large part of the traditional lifestyle. Swamps were used as duck hunting areas and deer were hunted inland. Berrypicking was often done in conjunction with fishing and hunting trips, with the most important berries being cranberries, huckleberries, blackberries, and salal.[86]

.jpg)

Society

Villages

Like other Indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast, the Suquamish originally lived in permanent villages along the shores of waterways. The villages comprised large rectangular longhouses constructed facing the water and were fit to house several families. The houses were constructed out of large cedar planks and could be up to six hundred feet long, divided into several rooms. Houses were made with two particular styles: the shed-roof style and the gable-roof style.[87]

During the summer, as the Suquamish visited hunting, fishing, and gathering sites, temporary settlements were erected out of portable frames covered in large woven cattail mats.[87]

Seasonal cycles

Like other Coast Salish peoples, traditional Suquamish life was dominated by seasonal cycles of harvest, religion, trade, and manufacture. The summer was spent harvesting food across the region. As fall came, the Suquamish travelled to participate in fall salmon runs in the territories of their allies. Trade was also a large part of this season, and the Suquamish obtained whale oil, razor clams, salmon, basketry, and beadwork from other tribes.[97] Fall and late summer was also the season to host inter-tribal gatherings and celebrations. Gambling, shinny (a type of field hockey), wrestling, and jumping contests were all held to celebrate the growing abundance of the season.[98] When winter fell, it became a time of repairing tools and crafting baskets and canoes. Winter was also the time of celebrations, where members of the tribe were educated in story, dance, and ceremonies.[97]

External relations

The Suquamish are closely tied in culture, language, and alliance, to all of the peoples around them. External connections were especially important to the Suquamish, whose territory lacked any major rivers. In order to gain access to the large salmon runs on the rivers nearby, they had to marry into neighboring groups who operated fisheries. Prime among these connections were the Duwamish and the Twana, in addition to common alliances with the nearby Klallam and Snohomish.[99] Part of the seasonal cycle, then, included travelling to areas such as Hood Canal and upper Puget Sound to visit with relatives and harvest resources not available in their core territory. The Suquamish were noted to have travelled as far as the Fraser River and the San Juan Islands in pre-treaty times.[94] They also engaged in trade with more distant peoples, such as the Yakama, to whom the Suquamish would often trade smoked salmon and dried clams.[100]

The Suquamish and their eastern neighbors, the Twana, had especially close ties. Suquamish and Twana families intermarried frequently and the Suquamish had affinal relations with most Twana communities. The Suquamish were frequently involved in Twana ceremonies and feasts, and the Twana were likewise often invited to Suquamish territory.[101] The Suquamish connections to the Twana were so deep that practically every Twana was bilingual in Twana and Lushootseed. This linguistic connection did not go both ways; other Coast Salish groups did not often learn Twana.[102]

Warfare

In the Southern Coast Salish region, warfare in the 19th century was largely defensive or retaliatory in nature, and relied upon the ambition of individual warriors. Villages were generally on good terms with their neighbors and with those that they had marriage ties. Individual warriors would lead small parties into enemy territories in order to capture slaves and loot, if not by intimidation than violence. If the raided village felt sufficiently provoked, they may organize a retaliatory raid against the aggressors. There was not generally large, professional armies, as there was no political system for mobilizing warriors across the region. The only recorded case of large-scale organized warfare was in the case of defensive actions taken against northern raiders in this century.[103]

Suquamish Indian Tribe

The aboriginal Suquamish are succeeded today by the Suquamish Indian Tribe, a federally recognized Native American tribe with its headquarters located at Suquamish, Washington. The Suquamish people living on the Port Madison reservation formed today's Suquamish Tribe in 1965, adopting a formal constitution, creating the tribal council, and becoming a member of the National Congress of American Indians.[87] They govern the Port Madison reservation, which was created for the Suquamish and Duwamish people by the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855.[43]

See also

- Suquamish Indian Tribe

- Port Madison Indian Reservation

- Kitsap (Suquamish leader)

- Chief Seattle

- Coast Salish

- List of Lushootseed-speaking peoples

Notes

References

- ^ a b c Bates, Hess & Hilbert 1994, p. 205.

- ^ a b c d Ruby, Brown & Collins 2010, p. 326.

- ^ a b c d Buerge 2017, p. 3.

- ^ Bates, Hess & Hilbert 1994, p. 202.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 2-3.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 48.

- ^ Elmendorf 1960, p. 31.

- ^ a b Elmendorf 1960, p. 292.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 3, 278.

- ^ a b Suttles & Lane 1990, p. 487.

- ^ a b c d Buerge 2017, p. 39.

- ^ a b Smith 1940, p. 18.

- ^ Bates, Hess & Hilbert 1994, p. 18.

- ^ a b Lane 1974, p. 1.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Spier 1936, p. 34.

- ^ a b Suttles & Lane 1990, p. 485.

- ^ Suttles, Wayne (1990). "Introduction". Northwest Coast. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 7. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 1–15.

- ^ Elmendorf 1960, p. 292, 320.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, Chase (March 1, 2021). "Estuary has new name, honoring tribe; you'll need to watch a video to pronounce it". The News Tribune. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c Smith 1941, p. 207.

- ^ a b Smith 1940, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Lane 1974, p. 3.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 1-2.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 2-3.

- ^ Elmendorf 1960, p. 55.

- ^ Spier 1936, p. 35.

- ^ a b c d e Lane 1974, p. 5.

- ^ a b Snyder 1968, p. 134-135.

- ^ a b c d Snyder 1968, p. 134.

- ^ a b c Buerge 2017, p. 38.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 196, 200.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d Snyder 1968, p. 133.

- ^ Snyder 1968, p. 132.

- ^ a b Snyder 1968, p. 131.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 219-220.

- ^ a b Snyder 1968, p. 130.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 50, 224.

- ^ Snyder 1968, p. 135.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 50, 224, 229.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 49, 222-223, 226.

- ^ a b c d Lane 1974, p. 10-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Ruby, Brown & Collins 2010, p. 327.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 27-29.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 29.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 30.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 232.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 16-17.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 25.

- ^ Waterman 2001, p. 226.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 41.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 42.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 43-44.

- ^ a b Buerge 2017, p. 44.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 44-45.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 45-46.

- ^ a b Buerge 2017, p. 46.

- ^ a b Buerge 2017, p. 49.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 48.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 53.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 53-54.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 58.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 60.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 74.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 91-92.

- ^ a b c Buerge 2017, p. 76-77.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 77-78.

- ^ a b Lane 1974, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Lane 1974, p. 8-9.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 124.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 127.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 9.

- ^ a b "Treaty of Point Elliott, 1855". Governors Office of Indian Affairs. State of Washington. Retrieved 2023-11-21.

- ^ Hilbert 1986, pp. 57–59.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 135.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 12-15.

- ^ a b Buerge 2017, p. 216.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 9-10.

- ^ Ruby, Brown & Collins 2010, p. 327-328.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 204.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 6-7.

- ^ Yardley, William (2011-08-12). "A Washington State Indian Tribe Approves Same-Sex Marriage". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ a b Ruby, Brown & Collins 2010, p. 328.

- ^ Ruby, Brown & Collins 2010, p. 329.

- ^ a b c d Lane 1974, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f "History & Culture". The Suquamish Tribe. Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ "About dxʷləšucid Lushootseed". Tulalip Lushootseed. 2014-12-05. Retrieved 2025-03-29.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 11-12.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 12.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 13.

- ^ a b Suttles & Lane 1990, p. 498-499.

- ^ a b Buerge 2017, p. 12-13.

- ^ a b c Lane 1974, p. 12-16.

- ^ a b c Lane 1974, p. 18-19.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 17-19.

- ^ a b Ruby, Brown & Collins 2010, p. 326-327.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 11.

- ^ Buerge 2017, p. 34.

- ^ Lane 1974, p. 3-4.

- ^ Elmendorf 1960, p. 293-294.

- ^ Elmendorf 1960, p. 281-283.

- ^ Suttles & Lane 1990, p. 495.

Bibliography

- Bates, Dawn; Hess, Thom; Hilbert, Vi (1994). Lushootseed Dictionary. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-97323-4. OCLC 29877333.

- Buerge, David M. (2017). Chief Seattle and the Town that Took his Name. Seattle: Sasquatch Books. ISBN 978-1-63217-345-4.

- Elmendorf, W. W. (1960). The Structure of Twana Culture. Pullman: Washington State University.

- Hilbert, Vi (taqʷšəblu) (1986). "When Chief Seattle (Siʔaɬ) spoke in 1855". International Conference on Salish (and Neighboring) Languages. 21: 44–59.

- Lane, Barbara (1974-12-15). Identity, Treaty Status and Fisheries of the Suquamish Tribe of the Port Madison Reservation (PDF).

- Ruby, Robert H.; Brown, John A.; Collins, Cary C. (2010). A Guide to the Indian Tribes of the Pacific Northwest. Civilization of the American Indian. Vol. 173 (3rd ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 9780806124797.

- Smith, Marian W. (1940). The Puyallup-Nisqually. New York: AMS Press (published 1969). doi:10.7312/smit94070. ISBN 9780231896849. LCCN 73-82360.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Smith, Marian W. (1941). "The Coast Salish of Puget Sound". American Anthropologist. 43 (2): 197–211 – via JSTOR.

- Snyder, Warren A. (1968). Southern Puget Sound Salish: Texts, Place Names, and Dictionary. Sacramento Anthropological Society.

- Spier, Leslie (1936). Tribal Distribution in Washington. General Series in Anthropology, no. 3. Menasha, WI: George Banta Publishing Company.

- Suttles, Wayne; Lane, Barbara (1990). "Southern Coast Salish". Northwest Coast. Handbook of North American Indians. Vol. 7. Smithsonian Institution. pp. 485–502. ISBN 0-16-020390-2.

- Waterman, T.T. (2001). Hilbert, Vi; Miller, Jay; Zahir, Zalmai (eds.). sdaʔdaʔ gʷəɬ dibəɬ ləšucid ʔacaciɬtalbixʷ - Puget Sound Geography. Lushootseed Press. ISBN 979-8750945764.