Structured literacy

Structured literacy (SL), according to the International Dyslexia Association (which coined the term), is the systematic teaching of reading that focuses on the following elements: [5]

- Phonology: the sound structure of spoken words and Phonemic awareness (the ability to recognize, segment, blend, and manipulate sounds)

- Sound-symbol association: using the Alphabetic principle to connect sounds (phonemes) to letters (graphemes)

- Syllables: part of a word with one vowel sound, with or without a consonant (e.g., The word reading has two syllables, "read" and "ing".)

- Morphology: the smallest unit of meaning in a language (e.g., The word unbreakable has three morphemes, "un", "break", and "able".)

- Syntax: grammar, sentence structure, etc.

- Semantics: meaning.

SL is taught using the following principles:[1]

- Systematic: begin with the basic and easiest concepts and elements, and progress to the more difficult and complex

- Cumulative: each step builds on a previous step

- Explicit: direct teaching and continuous teacher-student interaction

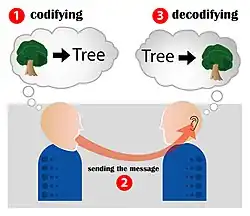

- Multisensory: using different senses (e.g., visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile) to enhance attention and memory

- Diagnostic: using informal and formal assessments to individualize instruction

The International Dyslexia Association provides a detailed outline of its Key Performance Standards of its Knowledge and Practice Standards for Teachers of Reading.[6]

It is beneficial for all early literacy learners, especially those with reading disabilities such as dyslexia.[12]

SL has many of the elements of systematic phonics and few of the elements of balanced literacy. The following is an explanation of how Structured literacy is different from Balanced literacy:[1]

| Feature | Structured literacy | Balanced literacy |

|---|---|---|

| Basis | Science of reading[13] | Whole language[13] |

| Areas covered | Phonology, phonemic awareness, sound-symbol association, syllables, morphology, syntax, and semantics[14] | Learn from exposure, reading, instruction, and support in multiple environments[14] |

| Teaching method | Direct, explicit, systematic, cumulative, and multisensory[14]

Mostly teacher-led (e.g., The teacher leads the students through decoding activities.)[15] Lessons involve phonics and word reading, from easier to more difficult[15] Corrective feedback: students are asked to "sound-out" the word[15] |

Implicit, constructivist, and less structured[16]

Often student-directed (e.g., independent learning, students choose reading material, etc.)[15] Lessons relate to comprehension of books or literature themes.[15] Corrective feedback: students are asked "does that make sense", and are told to check the cues (e.g., pictures, first letter, etc.)[15] |

| Phonics | Taught via the alphabetic principle, systematically, including the most frequent phonemes (sounds) and graphemes (letters), beginning with the easiest and progressing to the more complex[14] | Taught as needed via mini-lessons, or not at all[14] |

| Text for reading instruction | Decodable text until grade 2[15] | Leveled text, but not corresponding to phonics taught[15] |

| Reading | decoding and sounding out words[14] | read the whole word using cues (context, word analogies, and pictures) to guess the word[14] |

| Effectiveness | a mean unweighted effect size of .47, and a fixed weighted mean effect size of .44.

Structured literacy approaches "tend to yield larger positive effects on student learning compared to balanced literacy approaches", meta-analysis 2024.[17] |

a mean unweighted effect size of .21, and a weighted mean effect size of .33.[17] |

See also

References

- ^ a b c d "What Is Structured Literacy, International Dyslexia Association, Pikesville, MD, USA". 2016.

- ^ "Structured Literacy, An Introductory Guide, International Dyslexia Association, Pikesville, MD, USA" (PDF). 2019.

- ^ "Structured Literacy Instruction: The Basics, Reading rockets".

- ^ Spear-Swerling, Louise (2019). "EDUCATOR TRAINING INITIATIVES BRIEF Structured Literacy, an Introductory Guide".

- ^ Sources:[1][2][3][4]

- ^ "Knowledge and Practice Standards for Teachers of Reading". 2018.

- ^ Louise Spear-Swerling (2018-01-23). "Structured Literacy and Typical Literacy Practices". Council for Exceptional Children, Arlington, VA, USA. 51 (3). doi:10.1177/0040059917750160. S2CID 149516059.

- ^ Center, Yola; Freeman, Louela (1996). "The Use of a Structured Literacy Program to Facilitate the Inclusion of Marginal and Special Education Students into Regular Classes" (PDF). Sydney, NSW, Australia: School of Education Macquarie University.

- ^ Heidi Turchan (March 28, 2023). "Partner spotlight: Putting the science of reading into practice".

- ^ "Colorado dyslexia handbook, Structured literacy".

- ^ "Instructional Approaches in Language, Department of education, Ontario Canada". 2023.

- ^ Sources:[1][7][8][9][10][11]

- ^ a b "Four things you need to know about the new reading wars, Jill Barshay, The Hechinger Report, #2". 30 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gibson, Kenny; Hall, Julie Anne; Angrum, Cartessia (April 14, 2021). "Structured Literacy vs Balanced Literacy, Mississippi Department of Education" (PDF).

- ^ a b c d e f g h Louisa Cook Moats (2020). Speech to print, language essentials for teachers. p. 255. ISBN 9781681253305.

- ^ Lorimor-Easley, Nina A.; Reed, Deborah K. (April 9, 2019). "An Explanation of Structured Literacy, and a Comparison to Balanced Literacy, The University of Iowa".

- ^ a b Hansford, Nathaniel; Dueker, Scott; Garforth, Kathryn; Grande, Jill D. (2024). "Structured Literacy Compared to Balanced Literacy: A meta-analysis". Research Gate. doi:10.17605/OSF.IO/K7Y4C.