Standard of Ur

| The Standard of Ur | |

|---|---|

_(2).jpg) The Standard of Ur in the British Museum | |

| Material | shell, limestone, lapis lazuli, bitumen |

| Length | 49.53 cm (19.50 in) |

| Width | 21.59 cm (8.50 in) |

| Created | c. 2550 BC |

| Discovered | 1927 or 1928 Royal Cemetery at Ur 30°57′41″N 46°06′22″E / 30.9615°N 46.1061°E |

| Discovered by | Leonard Woolley |

| Present location | British Museum, London |

| Identification | 121201 Reg number:1928,1010.3 |

| Culture | Sumerian |

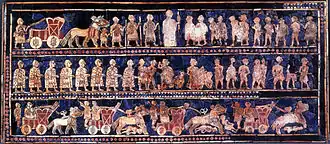

The Standard of Ur is a Sumerian artifact of the 3rd millennium BC that is now in the collection of the British Museum. It is thought to have decorated the outside a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 cm (8.50 in) wide by 49.53 cm (19.50 in) long, inlaid with a mosaic of shell, red limestone, and lapis lazuli.[1] It comes from the ancient city of Ur, located in modern-day Iraq west of Nasiriyah. It dates to the First Dynasty of Ur during the Early Dynastic III period and is around 4,600 years old.

The standard was probably constructed in the form of a hollow wooden box with scenes of war and peace represented on each side through elaborately inlaid mosaics. Although interpreted as a standard by its discoverer, its actual purpose is not known. It was found in a royal tomb in Ur in the 1920s next to the skeleton of a ritually sacrificed man who might have been its bearer "entirely covered with thousands of minute lapis-lazuli ball beads, they lay over and under the broken skull and were thick in the surrounding soil; it appeared that he had worn a cap which was parsemé with beads".[2] A shell cylinder seal with the name "é-zi" was found with the body.[3]

History

The artifact was found in one of the largest royal tombs in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, tomb PG 779, associated with Ur-Pabilsag, a king who died around 2550 BC.[4] Sir Leonard Woolley's excavations in Mesopotamia from 1927–1928 uncovered the artifact in the corner of a chamber, lying close to the shoulder of a man who may have held it on a pole.[5] For this reason, Woolley interpreted it as a standard, giving the object its popular name, although subsequent investigation has failed to confirm this assumption.[6]

The discovery was quite unexpected, as the tomb in which it occurred had been thoroughly plundered by robbers in ancient times. As one corner of the last chamber was being cleared, a workman spotted a piece of shell inlay. Woolley later recalled that "the next minute the foreman's hand, carefully brushing away the earth, laid bare the corner of a mosaic in lapis lazuli and shell."[7]

The Standard of Ur survived in only a fragmentary condition. The ravages of time over more than four thousand years caused the decay of the wooden frame and bitumen glue which had cemented the mosaics in place. The soil's weight had crushed the object, fragmenting it and breaking its end panels.[5] This made excavating the Standard a challenging task. Woolley's excavators were instructed to look for hollows in the ground created by decayed objects and to fill them with plaster or wax to record the shape of the objects that had once filled them, rather like the famous plaster casts of the victims of Pompeii.[8]

When the remains of the Standard were discovered by the excavators, they found that the mosaic pieces had kept their form in the soil, while their wooden frame had disintegrated. They carefully uncovered small sections measuring about 3 cm2 (0.47 sq in) and covered them with wax, enabling the mosaics to be lifted while maintaining their original designs.[2] For display in 1928 the pieces were consolidated with paraffin which caused deterioration. The Standard was completely dismantled and reassembled in 1973, with the inlays on the end panels being adjusted at that time.[9][10]

Description

The present form of the artifact is a reconstruction, presenting a best guess of its original appearance.[5] It has been interpreted as a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 cm (8.50 in) wide by 49.53 cm (19.50 in) long, inlaid with a mosaic of shell, red limestone, and lapis lazuli. The box has an irregular shape with end pieces in the shape of truncated triangles, making it wider at the bottom than at the top.[6]

Inlaid mosaic panels cover each long side of the Standard. Fantastical inlaid scenes decorate the trapezoidal ends, though they have received minimal notice. Each presents a series of scenes displayed in three registers: upper, middle, and bottom. The two mosaics have been dubbed "War" and "Peace" for their subject matter, respectively a representation of a military campaign and scenes from a banquet. Both sides use hierarchical proportion in the depiction of the forms of the art, with the most important individuals appearing larger than less important ones.[11][12]

Mosaic scenes

"War" is one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian army, engaged in what is believed to be a border skirmish and its aftermath. Related scenes were shown on sealings found in the Royal Cemetery.[13] The "War" panel shows a figure, often taken as a king though the figure lacks any of the standard indicator of kingship, in the middle of the top register, standing taller than any other figure, with his head projecting out of the frame to emphasize his supreme status – a device also used on the other panel.[14][15]

He stands in front of his bodyguard and a four-wheeled wagon (vs cart or chariot), drawn by a team of some sort of equids, possibly onagers or domestic asses or even kunga; horses were only introduced in the region in the early 2nd millennium BC.[16][17][18] He faces a row of prisoners, all of whom are portrayed as naked, bound and injured with large, bleeding gashes on their chests and thighs – a device indicating defeat and debasement.[6]

In the middle register, eight virtually identically depicted soldiers give way to a battle scene, followed by a depiction of enemies being captured and led away. The soldiers are shown wearing leather cloaks and helmets; actual examples of the sort of helmet depicted in the mosaic were found in the same tomb.[8]

The lower register shows four wagons, each carrying a driver and a warrior (carrying either a spear or an axe) and drawn by a team of four equids. The wagons are depicted in considerable detail. Each has solid wheels (spoked wheels were not invented until about 1800 BC) and carries spare spears in a container at the front. The arrangement of the equids' reins is shown in detail, illustrating how the Sumerians harnessed them without using bits, which were introduced a millennium later.[8] The wagon scene evolves from left to right in a way that emphasizes motion and action through changes in the depiction of the animals' gait. The first wagon team is shown walking, the second cantering, the third galloping and the fourth rearing. Naked and bleeding prone enemies are shown lying under the hooves of the latter three groups, symbolizing the potency of a wagon attack.[6][19]

"Peace" portrays a banquet scene. The king again appears in the upper register, sitting on a carved stool on the left-hand side. He is faced by six other seated participants, each holding a cup raised in his right hand. They are attended by various other figures including a long-haired individual, possibly a singer, who accompanies a lyrist. In the middle register, bald-headed figures wearing skirts with fringes parade animals, fish and other goods, perhaps bringing them to the feast. An alternate proposal is that they are spoils of war being paraded.[20] The bottom register shows a series of figures dressed and coiffed in a different way from those above, carrying produce in shoulder bags or backpacks, or leading equids by ropes attached to nose rings.[6]

There has been much speculation on the origins and professions of the various non-royal humans (and on the species of various animals) on the standard ranging from Sumerians to "northerners" to being from completely outside the Mesopotamian plain.[21][22][23]

Interpretations

| External media | |

|---|---|

| |

| Audio | |

| Video | |

The original function of the Standard of Ur is not conclusively understood. Woolley's suggestion that it represented a standard is now thought unlikely. It has also been speculated that it was the soundbox of a musical instrument.[5] Paola Villani suggests that it was used as a chest to store funds for warfare or civil and religious works.[24] It is impossible to say for sure, as the artifact does not have an inscription that would provide context.

Although the side mosaics are usually referred to as the "war side" and "peace side", they may be a single narrative – a battle followed by a victory celebration. This would be a visual parallel with the literary device of merism, used by the Sumerians, in which the totality of a situation was described through the pairing of opposite concepts.[25]

The scenes depicted in the mosaics were reflected in the tombs where the "Standard" was found. The skeletons of attendants and musicians were found accompanying the remains of the kings, as was equipment used in both the "War" and "Peace" scenes of the mosaics. Unlike ancient Egyptian tombs, the dead were not buried with provisions of food and serving equipment. Instead, they were found with the remains of meals, such as empty food vessels and animal bones. They may have participated in one last ritual feast, the remains of which were buried alongside them, before being put to death, possibly by poisoning, to accompany their master in the afterlife.[26]

See also

References

- ^ Hauptmann, Andreas, Klein, Sabine, Paoletti, Paola, Zettler, Richard L. and Jansen, Moritz, "Types of Gold, Types of Silver: The Composition of Precious Metal Artifacts Found in the Royal Tombs of Ur, Mesopotamia", Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und vorderasiatische Archäologie, vol. 108, no. 1, pp. 100-131, 2018

- ^ a b [1] Woolley, Leonard, "The Royal Cemetery: a report on the predynastic and Sargonid graves excavated between 1926 and 1931", Ur Excavations II, Publications of the Joint Expedition of the British Museum and of the University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, to Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press, 1934

- ^ Marchesi, Gianni, "Who Was Buried in the Royal Tombs of Ur? The Epigraphic and Textual Data", Orientalia, vol. 73, no. 2, pp. 153–97, 2004

- ^ Hamblin, William James, "Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: holy warriors at the dawn of history", Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-25588-2

- ^ a b c d [2]Standard of Ur at the British Museum

- ^ a b c d e Zettler, Richard L.; Horne, Lee; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly, "Treasures from the royal tombs of Ur", UPenn Museum of Archaeology, 1998 ISBN 978-0-924171-54-3

- ^ Leonard Woolley, "Excavations at Ur: a record of twelve years' work", Crowell, 1965 ISBN 978-0815201106

- ^ a b c Collon, Dominique, "Ancient Near Eastern Art", University of California Press, 1995 ISBN 978-0-520-20307-5

- ^ Collins, Sarah, "Standard of Ur (Object in Focus)", British Museum Press, 2015

- ^ Old Sumerian Art - L. Legrain - The Museum Journal Volume XIX / Number 3 - 1928

- ^ Renette, Steve, "Feasts on Many Occasions: Diversity in Mesopotamian Banquet Scenes during the Early Dynastic Period", Feasting in the Archaeology and Texts of the Bible and the Ancient Near East, edited by Peter Altmann and Janling Fu, University Park, USA: Penn State University Press, pp. 61-86, 2015

- ^ Jean-Claude Margueron, "L’étendard d’Ur : récit historique ou magique ?", Collectanea Orientalia, Civilsations du Proche-Orient, Série I : Archéologie et environnement, vol. 3, pp. 159-169, 1996

- ^ Petr Charvát, "Early Ur - War Chiefs and Kings of Early Dynastic III", Altorientalische Forschungen, vol. 9, no. JG, pp. 43-60, 1982

- ^ Couturaud, Barbara, "Kings or Soldiers? Representations of Fighting Heroes at the End of the Early Bronze Age", Tales of Royalty: Notions of Kingship in Visual and Textual Narration in the Ancient Near East, edited by Elisabeth Wagner-Durand and Julia Linke, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, pp. 109-138, 2020

- ^ Miglus, P. A., "Kings Go into Battle: Representation of the Mesopotamian Ruler as a Warrior", in P. Abrahami and L. Battini (eds.), Les armées du Proche-Orient ancien (IIIe-Ier mill. av. J.-C.): Actesdu colloque international organisé à Lyons les 1er et 2 décembre 2006, Maison de l’Orient et de la Médi-terranée, BAR IntSer 1855, Oxford: Hedges, pp. 231–46, 2008

- ^ Orlando, Ludovic, "The Other Horse" , in Horses: A 4,000-Year Genetic Journey Across the World, Princeton University Press, pp. 86-98, 2025

- ^ Brown, Marley, "Kunga Power", Archaeology, vol. 75, no. 3, p. 13, 2022

- ^ Clutton-Brock, Juliet, "Horse power: a history of the horse and the donkey in human societies", 1992 ISBN 978-0-674-40646-9

- ^ Cornelius, I., "Memories of Violence in the Material Imagery of Carchemish and Samʾal: The Motifs of Severed Heads and the Enemy under Chariot Horses", in Collective Violence and Memory in the Ancient Mediterranean. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, pp. 110–127, 2023

- ^ Recht, Laerke, "Animals, Violence, and Inequality in Ancient Mesopotamia", Violence and Inequality: An Archaeological History, University Press of Colorado, pp. 162-192, 2023

- ^ Ławecka, Dorota, "Who Were the Tribute-Bearing People on the ‘Standard of Ur’?", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 76, no. 2, pp. 337–48, 2017

- ^ Nadali, Davide, "Monuments of war, war of monuments: Some considerations on commemorating war in the Third Millennium BC", Orientalia 76.4, pp. 336-367, 2007

- ^ Ruth Mayer-Opificius, "Bemerkungen zur sogenannten Standarte aus Ur.(Remarques sur l'Etendard d'Ur)", Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orientgesellschaft zu Berlin Berlin 108, pp. 45-52, 1976

- ^ Da Rios, Giovanni, "Settemila anni di strade", Milano:Edi-Cem , 2010

- ^ Kleiner, Fred S., "Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective", Cengage Learning, 2009 ISBN 978-0-495-57360-9

- ^ Cohen, Andrew C., "Death rituals, ideology, and the development of early Mesopotamian kingship: toward a new understanding of Iraq's royal cemetery of Ur", BRILL, 2005 ISBN 978-90-04-14635-8

External links