Simon Girty

Simon Girty (14 November 1741 – 18 February 1818) was an interpreter and intermediary with the British Indian Department during the American Revolutionary War and the Northwest Indian War. He and his brothers James and George were captured as children and adopted by Native Americans. Freed after living with the Seneca for several years, Girty worked as an interpreter and hunter. During the Revolutionary War he became disillusioned with the Patriot cause, and in 1778, fled to Fort Detroit where he was hired as an interpreter for the British Indian Department. In 1780, Girty accompanied Britain's Indigenous allies during an expedition against Kentucky's frontier settlements, and was present at Lochry's Defeat in 1781. Girty was held complicit when the Delaware tortured Colonel William Crawford to death following the Battle of Sandusky. He continued to serve with the British Indian Department for many years after the 1783 Peace of Paris. Girty witnessed the defeat of the Northwestern Confederacy at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794. He retired from the Indian Department in 1795, and until his death in 1818, lived on land granted to him by the British at the mouth of the Detroit River in Upper Canada.

Early life

Simon Girty was born in 1741 to Simon Girtee and Mary Newton at Chamber's Mills in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. Girty's father emigrated to Pennsylvania sometime in the early 1730s from Ireland, and was employed as a packhorse driver and trader. Girtee and Mary had four sons: Thomas, Simon, James, and George.[1]

In 1749, Girty's father moved his family across the Susquehanna River and squatted on land that had yet to be ceded to the Pennsylvanian government. An Indigenous delegation met with Pennsylvania governor James Hamilton who ordered the squatters evicted. In 1750, Girtee was fined and forced to return to Lancaster County.[2]

Late in 1750, Girty's father was killed during an argument with Samuel Saunders (or Sanders). Saunders was arrested, tried, convicted of manslaughter, and imprisoned.[3] While court records show that Saunders was the culprit, early biographers such as Consul Willshire Butterfield recorded that Girty's father was killed during "a drunken frolic" by an Indigenous man named The Fish.[4]

In 1753, Mary Girty married John Turner. Their son John was born the following year. Following a land purchase by the Penn family in 1754, Turner brought his family across the Susquehanna and settled on Shermans Creek close to where the Girtys had lived previously.[5]

During the French and Indian War, Turner brought his wife and children to Fort Granville for protection. In July 1756, the fort was besieged by a combined French and Indigenous force led by Louis Coulon de Villiers. Following the fort's surrender, Turner and his family were taken captive by the Shawnee and brought to Kittanning. The family was forced to watch as John Turner was tortured to death. Mary and her youngest son were then separated from the older boys, taken to Fort Duquesne and afterwards held captive by the Delaware.[6]

Kittanning was destroyed in September 1756 during an expedition led by Lieutenant Colonel John Armstrong. Thomas was rescued but Simon, James and George remained captives. The three boys were soon separated. Simon was given to the Seneca, James to the Shawnee, and George to the Delaware.[7]

Girty was adopted by a Seneca family following rituals that included running the gauntlet. He lived with the Seneca in western Pennsylvania for several years, and was mentored by the influential leader Guyasuta. Girty became fluent in Seneca and also learned to speak several other Iroquoian languages. Some sources state that Girty was turned over to the English at Fort Pitt following the 1758 Treaty of Easton.[8][9] Other sources maintain that he continued to live with the Seneca until the end of Pontiac's War in 1764.[10][11]

Lord Dunmore's War

Girty was reunited with his family at the home of his brother Thomas who had settled at Squirrel Hill a few miles east of Pittsburg. George and their mother had been freed a few years earlier and were living with Thomas. James was returned from captivity at the same time as Simon, and their half-brother, John Turner, was repatriated in May 1765. For the next several years Girty was employed as an interpreter by British Indian Department agent Alexander McKee, and as a hunter by George Morgan of the Philadelphia trading firm Baynton, Wharton, and Morgan. In the summer of 1768, Girty was hired to lead a buffalo hunting expedition on the Cumberland River. Girty was one of the few who escaped when the expedition was ambushed by a Shawnee war party. Later that year Girty and McKee served as interpreters at a conference between Sir William Johnson, his deputy George Croghan, and representatives of the Iroquois that led to the Treaty of Fort Stanwix. In 1772 and 1773, McKee hired Girty to escort Guyasuta to meetings with Johnson at Johnson Hall in Tryon County, New York.[12]

The Treaty of Fort Stanwix extended the western boundary of Virginia into present-day Kentucky and West Virginia, and opened the region south of the Ohio River to European settlement. The Shawnee, however, refused to recognize the authority of the Iroquois to cede the area. Although the Iroquois claimed sovereignty by right of conquest, the Shawnee had long used the land as their traditional hunting grounds. Shawnee raids on isolated farms began shortly after settlers began to arrive and soon intensified.[13]

At Fort Pitt, McKee relied on Guyasuta and the Delaware sachem Koquethagechton, commonly known as White Eyes, to dissuade the Delaware, Mingo and Wyandot from joining the Shawnee, with Girty serving as a messenger and interpreter. On 30 April 1774, however, Daniel Greathouse and his followers massacred thirteen peaceable Mingo at Baker’s Bottom on the Ohio River. In retaliation, Talgayeeta, the Mingo leader known as Logan, whose family were among the victims, began attacking farms in the Monongahela River valley.[14]

In May 1774, John Murray, 4th Earl of Dunmore used his executive power as Virginia's royal governor to mobilize the county militias and take action "to pacify the hostile Indian war bands."[15] By the beginning of October, 1,200 men had assembled at Fort Gower at the confluence of the Ohio and Hockhocking rivers. Dunmore planned to rendezvous with a body of 800 men commanded by Colonel Andrew Lewis (soldier) before moving against the Shawnee villages on the Scioto River.[13] Girty was employed by Dunmore as a scout and messenger.[16]

On October 8, Girty arrived at Lewis's encampment at the confluence of the Kanawha and Ohio rivers with a dispatch from Dunmore, then returned to Fort Gower that evening.[17] Two days later the encampment was attacked by Shawnee warriors led by Hokoleskwa, commonly known as Cornstalk. The Battle of Point Pleasant lasted for hours until Lewis was able to force the Shawnee to withdraw back across the Ohio River. The Virginians suffered 75 killed and 140 wounded in "a hard-fought battle" that raged from sunrise to sunset.[13]

On October 11, Dunmore departed Fort Gower and advanced towards the Scioto River. He established Camp Charlotte on the Pickaway Plains close to several Shawnee villages. Hokleskwa sent a message to the Virginians requesting a meeting to discuss peace. John Gibson and Girty were dispatched with Dunmore's reply. On October 19, Hokleskwa and other Shawnee leaders meet with Dunmore at Camp Charlotte. The Shawnee agreed to end their raids, repatriate their captives, and relinquish any claim to the territory south of the Ohio River.[13]

Talgayeeta, who had not been at the Battle of Point Pleasant, did not attend the Camp Charlotte meeting. Girty was sent to find the Mingo leader and convince him to meet with Dunmore. Talgayeeta refused but had Girty memorize a carefully worded message in which the Mingo leader declared that "I have fully glutted my vengeance. For my country, I rejoice at the beams of peace." Upon his return to Camp Charlotte, Girty dictated the message to Gibson who presented it to Dunmore.[18]

American Revolutionary War

Two month prior to the start of the Revolutionary War, Girty took an oath of allegiance to George III and was appointed a lieutenant in the Virginia militia. He lost his commission when the militia was disbanded a few months later.[19] The following year Girty was hired as a interpreter by Morgan who had been appointed Commissioner for Indian Affairs. Girty was discharged after three months. In 1777, he worked as a recruiter for the 13th Virginia Regiment. He was promised a captaincy but was made a lieutenant instead. When the regiment was sent to Charleston, Girty remained behind on detached duty. He resigned his commission in August 1777.[20] A month later, rumors of a Loyalist conspiracy led to the arrest of Girty, McKee and a few others. Girty was acquitted but remained under suspicion.[21] Girty was then hired by the commander of the Western Department of the Continental Army, Brigadier General Edward Hand, to meet with the western Seneca and confirm if they were maintaining their neutrality. He met with Guyasuta who reluctantly decided to turn Girty over to the British. Girty escaped from the Seneca and return safely to Pittsburg.[22][23]

In February 1778, Girty served as an interpreter during the expedition known as the Squaw Campaign. Hand intended to capture a British supply depot at the mouth of the Cuyahoga River but failed to control his men when they encountered a cluster of cabins that housed a small number of neutral Delaware. A old man and woman were killed and another woman wounded. Girty, who had not been present, later guided a few of Hand's men to a place on the Mahoning River known as the Salt Licks. They discovered a group of women and children, and took one of the women prisoner. The following morning, two of the men were scouting the area when they encountered a youth shooting birds and killed him. Girty rejoined Hand and was asked to guide the expedition back to Fort Pitt. Due to an early thaw, swollen streams and constant rain, Hand had decided to abandon the campaign.[24]

On March 28, 1778, Girty, McKee and a few others left Pittsburg with the intention of joining the British at Detroit. Girty's motivation for his defection is uncertain, but was likely the combination of his embitterment towards Patriot officials, the attitude of many Americans towards Indigenous people, and the influence of his friend and staunch Loyalist Alexander McKee.[25] Girty and McKee first went to Coshocton and spoke to an assembly of the Delaware to convince them to abandon their neutrality and support the British. Hopocan, known as Captain Pipe, advocated war, however, Koquethaqechton counselled peace. The Delaware elected to remain neutral, however, Hopocan's war faction later split from the peace faction.[26]

Girty arrived at Detroit on April 20, 1778 and was hired by Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton as an interpreter in the British Indian Department. Meanwhile in Pennsylvania, Girty was indicted for treason and convicted in absentia. A bounty of $800 was placed on his head. Girty was sent to work first with the Mingo but was later assigned to the Wyandot who lived on the Sandusky River. In September, he accompanied a large war party that staged raids in western Pennsylvania. Simon's instructions were to "protect defenceless persons and prevent any insult or barbarity being exercised on the Prisoners."[27]

Girty travelled to the town of Wakatomika on the Mad River in October 1778 and learned that the Shawnee were intending to burn one of their captives. Girty recognized the prisoner as Simon Kenton who he had befriended during Dunmore's War. Girty convinced the Shawnee to spare Kenton's life. When the Shawnee later recanted their decision, Girty convinced them that Kenton should be brought to the Wyandot village of Upper Sandusky for the execution. With the help of Logan, he arranged for trader Pierre Drouillard to impersonate a British officer who told the Shawnee that Lieutenant Governor Hamilton wanted to question Kenton and would pay for him in rum and tobacco. Not wanting to offend Hamilton the Shawnee agreed. Kenton was taken to Detroit, questioned, and held as a prisoner of war until his escape a few months later.[28]

Fort Laurens

In November 1778, Brigadier General Lachlan McIntosh, who had succeeded Hand, began construction of Fort Laurens on the Tuscarawas River in preparation for a spring campaign against Detroit. Due to a shortage of provisions, McIntosh decided to return to Fort Pitt leaving 150 men of the 13th Virginia Regiment to garrison the fort.[29]

Girty went to Fort Laurens in January with a small force of Mingo. They were too late to intercept a pack train bringing supplies but successfully ambushed the escort as it returned to Fort Pitt. Two Americans were killed and one taken prisoner. Girty brought the prisoner to Detroit and requested British regulars be assigned to help take the fort. Captain Henry Bird of the 8th Regiment and a small number of regulars accompanied Girty to Upper Sandusky where they were joined by a few hundred Mingo and Wyandot. The siege began on February 22, 1779 when a work party was surprised outside the fort. All 19 were killed and scalped. Due to the harsh winter conditions, Bird lifted the siege four weeks later, shortly before American reinforcements arrived. Colonel Daniel Brodhead who had replaced McIntosh as commander of the Western Department, decided that Fort Lauren's location was untenable and ordered the fort abandoned.[29]

Ambush on the Ohio River

In August 1779, Girty was at Detroit when his brother George arrived from Kaskaskia leading a small group of escaped prisoners. George had previously served aboard an American gunboat on the Mississippi River but had been accused of treason after conspiring to help prisoners escape. George was immediately hired by the British Indian Department as an interpreter.[30]

Two months later, Simon and George were with a party of about 120 Shawnee and Wyandot warriors who laid a ambush on the Ohio River that killed 40 American soldiers and reaped a tremendous score of munitions and supplies. Colonel David Rogers commanded a pair of keelboats carrying gunpowder, lead, rifles, several kegs of rum and other supplies to Fort Pitt which he had purchased from the Spanish at New Orleans. Rogers was joined by a third keelboat at the Falls of the Ohio. As they approached the confluence with the Licking River, lookouts spotted a canoe on the river ahead and opened fire. The warriors headed to shore and fled into the woods. Rogers beached the keelboats and set off in pursuit but quickly ran into a hail of bullets. A second group of warriors attacked the boats, but the men who had been posted there managed to get one of the vessels out into the river and escape. One of the few prisoners taken was retired Colonel John Campbell who Simon placed under his protection and took to Fort Detroit.[31]

Invasion of Kentucky

In May 1780, the British mounted an expedition against American forces at the Falls of the Ohio. Major Arent DePeyster, who had succeeded Hamilton as Fort Detroit's commandant after the latter was taken prisoner at Vincennes, selected Henry Bird to lead a force of 150 soldiers from the 8th Regiment, 47th Regiment, Royal Artillery, and Detroit militia, accompanied by 100 Odawa and Ojibwe warriors as well as several British Indian Department personnel including Girty and his brothers. At the confluence of the Ohio and Great Miami rivers they rendezvoused with McKee and several hundred Shawnee, Delaware and Wyandot warriors from the Ohio Country. Although Bird's orders were to attack Fort Nelson at the Falls of the Ohio, he was overruled by his Indigenous allies who preferred to target the isolated settlements on the Licking River.[32]

In late June, Bird's expedition besieged the fortified settlements of Ruddle's Fort and Martin's Station. At Ruddle's Fort, Girty was sent to negotiate terms for the fort's surrender. Despite the efforts of Girty, Bird and McKee, a number of non-combatants were killed or wounded when the Indigenous warriors ignored the terms, burst into the fort and took most of the inhabitants captive.[33] Bird later reported that the warriors "rush'd in, tore the poor children from their mothers Breasts, killed a wounded man and every one of the cattle."[34]

Bird was able to prevent a repeat when Martin's Station surrendered, however, both forts were plundered and burned. Afterwards, Bird's regulars and militia escorted about 150 men, women and children to Detroit, arriving there in early August. Of the roughly 250 prisoners taken by the Indigenous auxiliaries, most were brought to Detroit, but a number were killed en route in what historian Russell Mahan has called a death march. A few others, mostly young women and children, were held captive until the end of the war and in some cases for years afterwards.[33]

Several enslaved persons were taken during the expedition and divided among the members of the British Indian Department. Girty was given a young man named Scipio who he soon freed.[35]

Lochry's Defeat

In the winter of 1781, Girty led a few Wyandot warriors from Upper Sandusky to the Falls of the Ohio in order to spy on the Americans. They captured three soldiers from Fort Nelson and discovered that Brigadier General George Rogers Clark was recruiting men and stockpiling supplies at Wheeling and Fort Pitt in anticipation of an expedition against Detroit later that year. Clark planned to proceed down the Ohio River from Fort Pitt to Wheeling and then continue on to Fort Nelson before heading north. Girty hurried to inform McKee at Roche de Bout on the Maumee River who in turn notified DePeyster at Detroit. Girty then proceeded to Upper Sandusky. As he entered the Wyandot village he encountered a young captive who had broken away from his guards. The captive was 18-year-old Henry Baker who the Wyandot had planned to burn. After hearing Baker's story, Girty convinced the Wyandot to spare Baker's life and take him to Detroit for ransom.[36]

DePeyster met with Indigenous leaders in April, after which Girty and McKee began the slow process of gathering warriors to counter Clark. In early August, Joseph Brant, who had been sent to Detroit from Fort Niagara, led about 90 Shawnee and Wyandot warriors to the confluence of the Great Miami and Ohio rivers. With Brant was Girty's brother George. Because he was severely outnumbered, Brant had to allow the main body of Clark's troops to pass on the Ohio unscathed, but a few days later successfully ambushed a contingent of Pennsylvania militia led by Colonel Archibald Lochry , killing 37 and capturing 64.[37]

Brant later rendezvoused with Girty and McKee who had brought with them 300 additional warriors and Captain Andrew Thompson's company of Butler's Rangers. They set off in pursuit of Clark but soon abandoned the chase when they realized that the Americans had too great a lead. While encamped on the banks of the Ohio, Brant got drunk and began to brag. He claimed sole responsibility for Lochry's defeat, and boasted that had taken the most prisoners. Girty, who had also been drinking heavily, believed George deserved some of the credit and accused Brant of lying. Later that evening Brant, sword in hand, came up behind Simon and dealt him a severe head wound. It took Girty several months to recover and left him with a scar that he hid beneath a red bandana. For the rest of his life he suffered with episodes of dizziness, blurred vision, and severe headache.[38]

Death of William Crawford

In May 1782 a mounted expedition of 480 volunteers led by Colonel William Crawford set out from Fort Pitt to attack Indigenous settlements on the Sandusky River. They were met by a detachment of Butler's Rangers led by Captain William Caldwell, and a combined force of Delaware led by Hopocan and Wyandot led by Dunquat, also known as the Half-King. A number of British Indian Department personnel were also present including Girty and Elliott.[39]

During the two day battle, the Americans took up a defensive position on a wooded knoll which they called Battle Island. On the morning of the second day, Girty approached the American lines requesting a parley. He called on Crawford to surrender but was rebuked. Following the arrival of a body of Shawnee that afternoon, Crawford resolved to withdraw as his men were in danger of being encircled. An orderly retreat was planned, however, the withdrawal dissolved into chaos when Indigenous scouts detected the Americans leaving. Many were killed or taken prisoner as they fled singly or in small groups.[39]

Crawford was captured by the Delaware who decided to execute him in retaliation for the Gnadenhutten Massacre. Crawford's surgeon, Dr. John Knight, witnessed Crawford's execution, and held Girty responsible for not intervening. An account of his ordeal, significantly embellished by Hugh Henry Brackenridge, was widely published the following year, and is the main source of Girty's reputation as a "white savage."[40][41][42]

Crawford was taken to Upper Sandusky where he asked to meet with Girty. Girty told Crawford that the Delaware blamed the American colonel for the massacre of non-combatants at the Moravian village of Gnadenhutten three months earlier. Crawford denied any involvement and begged Girty to arrange ransom in exchange for military intelligence. Girty promised to do all that he could, but encouraged Crawford to attempt to escape. Crawford was then taken to an abandoned village where Knight and other captives were being held. Crawford and Knight were forced to run a gauntlet while the others were tomahawked, scalped and mutilated.[39]

Crawford's "trial" was held at Hopocan's town with Girty translating. Hopocan sentenced Crawford to death by fire. Girty attempted to bargain for Crawford's life but was berated by Hopocan and threatened with death.[43] Crawford and Knight were taken to a grove of oaks west of Hopocan's town. Crawford was stripped naked, beaten, then tied to a post. The Delaware fired numerous powder charges into his body then cut off his ears. They applied burning sticks to his bare skin and threw hot coals at his feet. Eventually Crawford collapsed and was scalped. He died soon afterwards and his corpse was burned.[39]

There are conflicting reports of Girty's behavior at Crawford's death. At some point Crawford called out to Girty to end his suffering and shoot him. According to Knight:

In the midst of these extreme tortures, Crawford called to Simon Girty and begged him to shoot him; but Girty making no answer he called to him again. Girty, then, by way of derision, told the colonel he had no gun, at the same time turning about to an Indian who was behind him, laughed heartily, and by all his gestures seemed delighted at the horrid scene.[44]

Knight later overpowered his single guard as he was being taken to a Shawnee village for his own execution. He arrived at Fort McIntosh three weeks later, starved and barely coherent. Knight was conveyed to Fort Pitt where he was debriefed by Brigadier General William Irvine. Irvine reported Crawford's death to George Washington. He wrote that "the unfortunate colonel ... was burned and tortured in every manner they could invent" and that "the colonel begged Girty to shoot him, but he paid no regard to the request."[45]

Girty's daughter Sarah, however, in a 1864 interview, told historian Lyman Draper that when Crawford called out to Girty, he explained that no one was permitted to interfere once the torture began. According to Sarah, Girty had tried everything he could possibly do to save Crawford.[46] Elizabeth Turner, who had been captured and adopted by the Wyandot in 1780, told her son that she witnessed Crawford's execution. She said that Girty offered his horse, rifle, and his enslaved servant Scipio as ransom, but was told that Crawford would only be spared if Girty took his place. She further said that Girty wept while witnessing Crawford ordeal.[47]

Girty reported Crawford's death to Caldwell, who in turn reported to DePeyster that "Crawford died like a hero; never changed his countenance tho's they scalped him alive, and then laid hot ashes upon his head; after which, they roasted him by a slow fire." DePeyster would later write: "Colonel Crawford, who commanded, was taken in the pursuit and put to death by the Delawares, notwithstanding every means had been tried by an Indian officer present, to save his life."[48]

Battle of Blue Licks

In August 1782, Girty, McKee, and Elliott accompanied William Caldwell and his company of Butler's Rangers along with 300 Shawnee warriors led by Blue Jacket in an attack on Bryan Station located east of present-day Lexington, Kentucky. Unable to breach the stockade, Caldwell ended the siege after two days. The following morning, just under 200 militia led by Colonel John Todd arrived at the station and set off in pursuit of Caldwell. On the morning of August 19, Todd's men reached the Licking River near a salt spring called the Blue Licks. When they spotted movement on the ridge opposite them, Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Boone urged caution, however, Major Hugh McGary insisted on attacking immediately. The Americans forded the river, dismounted, formed lines and began advancing up the slope. As Boone had suspected, Caldwell's force was waiting for them, concealed in ravines. In the ensuing battle, 77 Americans were killed including Todd and 12 were captured.[49]

Northwest Indian War

In October 1782, Major DePeyster received orders to cease offensive operations as negotiations to end the war were underway. Over the next few months, the British Indian Department was reduced in size, however, Girty remained on the payroll as an interpreter.[50]

News that the Treaty of Paris had been signed reached Detroit in May 1783. The treaty transferred control of the Trans-Appalachia region to the United States, but failed to address the territorial rights of the Indigenous people that lived there. In contravention of the treaty, Britain continued to occupy Detroit and a number of other posts on American soil.[51]

In July 1783, Girty was the principal interpreter at a meeting of Indigenous leaders at Detroit hosted by the head of the British Indian Department, Sir John Johnson. Johnson reassured the Indigenous delegates that Britain would continue to support their allies.[52] A larger meeting at Lower Sandusky was held in early September during which the attendees were told that the peace treaty had not altered the Ohio River boundary between Indigenous territory and land open to white settlement. The Indigenous leaders also accepted a proposal, put forward by Joseph Brant, to form a confederacy in order to present a united front in any negotiations with the Americans. They agreed that no land was to be ceded without the consent of the confederacy.[53]

In November, Girty was tasked with locating and repatriating captives held by the Shawnee and other tribes. One of the captives freed by Girty was 18-year-old Catharine Malott who married her rescuer in August 1784.[54] As Girty made his way from village to village, he encouraged Indigenous leaders to resist attempts by the Americans to coerce them into ceding territory.[55] In January 1785, however, representatives of the Lenape and Wyandot were forced to sign the Treaty of Fort McIntosh, surrendering land in what is now southern and eastern Ohio to the United States including the territory occupied by the Shawnee. A year later the Shawnee leader Moluntha was cowed into signing the Treaty of Fort Finney confirming the cession of land east of the Great Miami River. Many Shawnee, Lenape and Wyandot refused to accept the terms since those who had signed had not been authorized to make cessions.[56] Raiding, which had continued sporadically since the end of the Revolutionary War, intensified after Kentucky militia led by Benjamin Logan burned several Shawnee villages and murdered Moluntha in October 1786.[57]

In December 1786, Girty served as interpreter during a meeting at the Wyandot village of Brownstown. The delegates sent a carefully-worded message to the United States Congress declaring the treaties "void and of no effect" because land cessions could only be made by "the united voice of the confederacy." They asked Congress to send commissioners to a meeting at the Maumee Rapids, and demanded that until a new treaty was negotiated, the Americans had to prevent their surveyors and settlers from crossing the Ohio.[58]

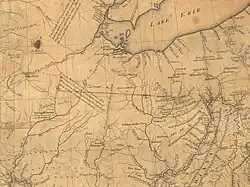

Congress ignored the message, and in July 1787, created the Northwest Territory. Arthur St. Clair was appointed as its governor.[59]. Congress quickly approved a proposal by the Ohio Company to purchase 1.5 million acres (607000 hectares) by the Ohio Company. The first settlers arrived in April 1788 and established Marietta at the confluence of the Muskingam and Ohio rivers.

St. Clair's approach to resolving conflict with Indigenous groups was aggressive and antagonistic. In January 1789, he met with some of the Wyandot and Lenape leaders and coerced them into signing the Treaty of Fort Harmer, confirming the earlier land cession. No Shawnee attended the meeting, and many of the Wyandot and Lenape who signed the treaty quickly disavowed it.[60]

Harmar's and St. Clair's defeats

In October 1790, Colonel Josiah Harmer led a punitive expedition against Miami and Shawnee villages on the Maumee River. Although five Indigenous towns were destroyed, ambushes killed or wounded over a quarter of Harmer's men. Girty was not present at any of the engagements that are collectively known as Harmer's Defeat, however, he helped plan simultaneous attacks on Dunlap's Station and Baker's Station in January 1791.[61] During the siege of Dunlap's, a prisoner named Abner Hunt was executed in view of the fort's defenders.[62][63] It has been claimed that Girty led the siege, however, available primary sources suggest that he was with the Shawnee who attacked Baker's Station.[64][65]

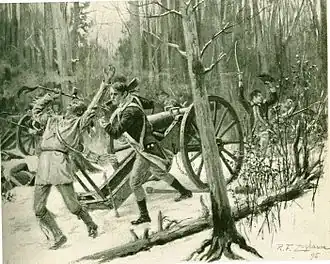

Later that year, St. Clair assembled a large force of regulars, six-month levies, and Kentucky militia at Fort Washington (now Cinncinati) on the Ohio River. Accompanied by a long baggage train, eight artillery pieces, teamsters, packhorse drivers, and some women and children, St. Clair's army proceeded slowly northwards towards the large Miami settlement of Kekionga. On 3 November, they encamped deep in Indigenous controlled territory alongside the Wabash River. No field fortifications were constructed and the river separated the militia from the regulars and levies.[66] Indigenous scouts tracked the movement of St. Clair's army, and more than a thousand Shawnee, Miami, Lenape, Wyandot, Odawa, Potawatomis, and Ojibwe warriors gathered to meet them. The warriors were led by Blue Jacket of the Shawnee and Little Turtle and the Miami. The Wyandot chose Girty to lead their contingent.[67]

The attack began at dawn on November 4 when Girty led an attack on the militia bivouac. The militia gave way almost immediately. They fled across the river and through the main camp but were prevented from escaping by the Odawa, Potawatomi and Ojibwe who had been positioned on the far side. The regulars and levies struggled to form lines as they came under fire from the Shawnee, Miami and Lenape advancing on the American centre. Although musket and artillery fire blunted the initial attack, the encampment was surrounded within minutes as the warriors swept past the American flanks. Indigenous marksmen quickly struck down officers and artillerymen. Bayonet charges pushed some of the warriors back, but others broke through the lines, overran the artillery, and began slaughtering some of the civilians. With casualties mounting and the artillery silenced, St. Clair ordered a retreat. A desperate charge opened an escape route, however, munitions, provisions, wagons, horses and the seriously wounded were abandoned. St. Clair's defeat, also known as the Battle of the Wabash, resulted in the deaths of 630 American soldiers. Many of the civilians that accompanied the expedition were either killed or captured including most of the women and children. After the battle, Girty was presented with three of the captured artillery pieces and also acquired a pair of silver-mounted pistols. The artillery pieces were later buried as Girty had no means of transporting them to Detroit.[68][69][70]

Battle of Fallen Timbers

As a result of the defeats of Harmer and St. Clair, the American government realized that a well-equipped and properly trained army of professional soldiers was needed. Congress provided funding for the Legion of the United States—a brigade-sized force of infantry, riflemen, calvalry and artillery. "Mad Anthony" Wayne, a Revolutionary War veteran, was appointed as its commander. Wayne established his headquarters at Pittsburg in April 1792 and began organizing and recruiting. In November, he moved 22 miles down the Ohio River and established the Legionville cantonment where he subjected his recruits to rigorous training and strict discipline. In April 1793, Wayne moved the Legion down the Ohio River to Fort Washington and the village of Cincinnati.[71]

In 1792, Girty had been the sole interpreter during Confederacy councils held at the confluence of the Auglaze and Maumee rivers, commonly known as the Glaize. In early September, he was in Pittsburg spying for the British, and ended up sitting close to Wayne in a tavern one evening.[72]

Aware that Wayne was building an army, some members of the Confederacy led by the Seneca orator Red Jacket indicated their willingness to make concessions to the Americans. The Shawnee, however, insisted that peace was not possible if the United States refused to recognize the Ohio River as the boundary between Indigenous and American territory. Finally, they agreed to send a message to the United States government. The Confederacy said that they would meet with American commissioners for peace talks, but insisted that all forts and settlements north and west of the Ohio River be removed.[73]

American commissioners met with a Confederacy delegation in August 1793 at the home of Matthew Elliot on the east side of the Detroit River. With Girty interpreting, the commissioners explained that removing settlers was impractical but that the United States was willing to negotiate a permanent boundary and pay compensation for land previously ceded. These proposals were rejected. The commissioners notified Wayne who ordered the Legion northwards into Indigenous territory.[74] In October, the Legion began construction of a fortified encampment which Wayne named Fort Greenville. Due to a substantial attack on a supply convoy in October, Wayne elected to forgo offensive action until the following year. In December, he led a detachment to the site of St. Clair's defeat, recovered some of the cannons buried there, and constructed Fort Recovery.[75]

In the spring of 1794, the British erected Fort Miami near the Maumee rapids in direct violation of United States sovereignty. The British wished to reassure the Indigenous population of Britain's continued support, and were concerned that Wayne might move against Detroit if the Confederacy was defeated.[51]

Girty accompanied Confederacy forces when they attacked a supply train encamped outside the walls of Fort Recovery in June. 40 American were killed and 300 packhorses were captured. Against the advice of Girty and Blue Jacket, Odawa and Ojibwe warriors then attempted to storm the fort but were driven back with heavy losses.[76]

At the end of the July 1794, Wayne's army started methodically moving north from Fort Greenville to the Glaize. The Legion erected field fortifications when they encamped after each day's march. As they approached the Glaize they encountered recently abandoned villages and fields of corn, beans, squash, melons and other vegetables. At the Glaize, the Legion constructed Fort Defiance then moved down the Maumee River to the rapids.[71]

The Battle of Fallen Timbers took place on the north side of the river, five miles upstream of Fort Miami, where a tornado had once struck, creating a mass of dead trees. Roughly 1,200 Confederacy warriors led by Blue Jacket, supported by about 100 Canadian volunteers led by William Caldwell, positioned themselves within the natural fortification and waited. Opposing them were 2,200 well-trained regulars and 750 mounted Kentucky volunteers.[71]

Only half of the warrior force was in position when Wayne launched his attack on the morning of August 20, 1794. Mounted Kentucky militia charged the Confederacy position and were met with a volley of musket fire. The militia fell back and several hundred warriors surged forward but were soon stopped by volleys of fire from Wayne's regulars. A series of bayonet charges pushed the warriors back into the tangle of unrooted trees. When the Legion's left turned into the Indigenous flank and engaged Caldwell's volunteers, the warriors broke and ran. Girty, McKee and Elliott could only watch as the panicked warriors fled towards Fort Miami. They had been given explicit orders not to participate in the battle. The warriors discovered that the fort's gate was barred against them. They continued their flight downriver to the mouth of the Maumee. Wayne's victorious forces marshalled outside Fort Miami where there was an exchange of angry words but no demand to surrender. A few days later the Legion withdrew back to Fort Greenville, burning deserted villages and fields of corn as they went.[71]

A month later, at Brownstown, Lieutenant Governor Simcoe, along with Girty, McKee and Elliot, tried to persuade the Confederacy leaders to continue the war, but the defeat had convinced them to accept the inevitable.[77] In August 1795, they met Wayne at Fort Greenville and signed the treaty he had prepared. With slight modifications the boundary established by the Treaty of Fort McIntosh was confirmed in exchange for goods and an annual payment.[71]

Jay's Treaty between the United States and Britain was ratified by Congress in 1795, resolving outstanding issues from the 1783 Treaty of Paris. In June 1796, the British withdrew from Detroit. It has been claimed that Girty was at a tavern in Detroit when the Americans arrived in early July but escaped arrest by swimming his horse across the Detroit River.[78]

Later years

After the Revolutionary War had draw to a close, Girty married and settled on the Canadian side of the Detroit River in what would eventually become Upper Canada. His wife was 19-year-old Catherine Malott who had been taken captive three years earlier. Catherine's mother had asked Girty to find her daughter. He found Catherine living in a Shawnee village and by the time he returned her to her mother they were in love. Girty married Catherine in August 1784. Four of their children survived to adulthood.[79]

Girty left the British Indian Department in 1795 but for the next few years was occasionally asked to serve as an interpreter. He hired men to farm his land including Indigenous people and often paid for their labor with rum. Girty drank heavily and increasingly suffered from debilitating headaches caused by the wound that Brant had given him. Catherine left Girty in 1798 but they later reconciled. In 1800, he broke either his leg or ankle in a fall and was left with a permanent limp. By 1809 he had begun to lose his sight.[80] During the War of 1812, Girty's son Thomas, who had joined the Essex militia, died of a fever reportedly contracted after rescuing a wounded militia officer during the Battle of Maguaga in August 1812. In 1813, when the British retreated from Amherstburg, Girty abandoned his home and spent the remainder of the war living at Burlington. Girty died on 18 February 1818, aged 77, and was buried with military honors on his farm.[81]

Myths and Perception

Girty's name has often been "synonymous with savagery and monstrosity."[41] Throughout the nineteenth century and into the twentieth, numerous authors portrayed Girty as a "monster" whose hands were "stained with the innocent blood of women and children."[47] For example, in his 1904 biography of Daniel Boone, John Peck wrote of Girty:

The shrieks and groans of helpless women and children, while butchered in the most horrid forms by ruthless savages, were music to his soul."[82]

Girty's infamy has been traced to the 1783 publication of Dr. Knight's account of Crawford’s death. Knight's Narrative, as edited by Brackenridge, was accepted "word-for-word" by most early historians. The accuracy of the narrative was seldom questioned until Parker B. Brown's 1987 article, "The Historical Accuracy of the Captivity Narrative of Doctor John Knight." Brown accused Brackenridge of rewriting history, and noted that Girty repeatedly tried to bargain for Crawford's life until he was warned off by Hopocan. Finally, Brown debunks the frequently quoted claim that Girty "laughed heartily, and by all his gestures seemed delighted at the horrid scene."[40]

Most scholars now accept that there was little Girty could do to prevent Crawford's death. Unlike his relationship with the Wyandot, Girty had little influence among the Delaware for whom the execution was justifiable retribution for the massacre at Gnadenhutten. Even the Moravian missionary John Heckewelder, the first to name Girty a "white savage," believed that "it was not in the power of any man" to save Crawford.[47]

Girty was vilified not only because he was a turncoat but because he was "race traitor" who championed the cause of Indigenous people and incited them to commit violence against whites.[41][83]. Early historians blamed Girty for "depredations he didn't commit and credited him for leadership he never possessed."[84] Some falsely claimed that Girty led the 1777 Siege of Fort Henry, and that he led the forces that routed the Kentucky militia at the Battle of Blue Licks. Perversely, some even made Girty the scapegoat for Gnadenhutten, arguing that had the "renegade" not incited Indigenous warriors to commit atrocities, the Americans would never have massacred the Moravian Lenape.[41]

Recent scholarship has used the textual evidence contained in the Wisconsin Historical Society's Draper Manuscript Collection to provide a more balanced and nuanced account of Girty's life. Historian Lyman Copeland Draper spent much of his career collecting information about Girty and other frontiersmen, and interviewed several who had known or encountered Girty. Among those interviewed were Elizabeth Turner who had been a captive of the Wyandot at the time Crawford was killed, and Girty's daughter Sarah.[85] Access to the Draper collection and other primary sources has permitted authors such as Colin Calloway, David Barr and Phillip Hoffman to dispel many of the myths surrounding Girty, however, he remains a controversial figure.[41][86][87]

Representation in culture

- In his 1846 novel Simon Girty: the Outlaw – An Historical Romance, Uriah James Jones depicts Girty as a "fanatical tomahawk-waving warmonger."[41]

- Simon Girty: "The White Savage"—A Romance of the Border is an 1880 novel by Charles McKnight that presents Girty in a somewhat more favourable light.[41]

- Girty is sympathetically portrayed in historical writer Allan Eckert's The Frontiersmen and That Dark and Bloody River, however, his use of invented dialogue and filling historical gaps with conjecture tends to damage his credibility.[41]

- Girty, along with his brothers, is vilified in novelist Zane Grey's frontier trilogy series Betty Zane, The Spirit of the Border and The Last Trail. In the second novel of the trilogy, Grey made Girty and his brother James directly responsible for the Gnadenhutten massacre.[88]

- Girty was played by American actor John Carradine in the 1936 film Daniel Boone directed by David Howard. In the film Girty is killed by Boone.[88]

- Girty is featured as one of the jury members in Stephen Vincent Benét's 1936 short story "The Devil and Daniel Webster" and in the 1941 movie of the same title. Benét describes Girty as “Simon Girty, the renegade, who saw white men burned at the stake, and whooped with the Indians to see them burn. His eyes were green like a catamount’s, and the stains on his hunting shirt did not come from the blood of the deer.”[88][89]

- Girty is the main character in Timothy Truman's two volume graphic novel Wilderness: The True Story of Simon Girty the Renegade.[41]

- Girty is a major character in Paul Green's Trumpet in the Land, Ohio's official state play, and the protagonist of Joe Bonamico and Mark Durbin's The White Savage.[90]

- Girty decision to fight on behalf of Native Americans is the inspiration for the 2002 song "Simon Girty's Decision," by Indigenous poet, composer and instrumentalist Todd Tamanend Clark.[91]

Notes

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 5.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 11.

- ^ Butterfield 1890, p. 5.

- ^ Butterfield 1890, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Butterfield 1890, pp. 7–8, 12.

- ^ Butterfield 1890, p. 15.

- ^ Butterfield 1890, p. 16.

- ^ Leighton 1983.

- ^ Butts 2011, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Butts 2011, pp. 43–53.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2024.

- ^ Williams 2017, pp. 71–73, 94.

- ^ Schenawolf 2015.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 74.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 75.

- ^ Butts 2011, pp. 54–56.

- ^ Calloway 1989, p. 44.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 111, 114.

- ^ Butts 2011, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 115–117.

- ^ "To George Washington from Colonel John Gibson, 5 December 1777". Founders Online. National Archives.

- ^ Sterner 2018.

- ^ Schock 2006, p. 21.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 134.

- ^ Butts 2011, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Butts 2011, pp. 84–92.

- ^ a b Sterner 2019.

- ^ Butterfield 1890, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 175–180.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 185.

- ^ a b Mahan 2020.

- ^ "Captain Henry Bird to Major Arent S. De Peyster, July 1, 1780. Historical Collections of the Michigan Pioneer and Historical Society, Volume 19, pp. 538-539.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 191.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 196–198.

- ^ Kelsay 1984, p. 313.

- ^ Butts 2011, pp. 129–132.

- ^ a b c d Sterner 2023.

- ^ a b Brown 1987.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Barr 1998.

- ^ Catalano 2015.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 226.

- ^ Brackenridge 1783, pp. 11–12.

- ^ "To George Washington from William Irvine, 11 July 1782". Founders Online. National Archives.

- ^ Catalono 2015, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Colwell 1994.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 229–231.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 235–243.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 248.

- ^ a b Werther 2023.

- ^ Butts 2011, p. 169.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 259–262.

- ^ Butts 2011, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 273.

- ^ White 1991, p. 437.

- ^ Calloway 2014, pp. 42–45.

- ^ Calloway 2014, p. 45.

- ^ Hoffman 2011, pp. 286–287.

- ^ Calloway 2014, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 295.

- ^ Sword 1985, p. 128.

- ^ Butterfield 1890, pp. 251–254.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 297.

- ^ Sugden 2000, p. 110-111.

- ^ Buffenbarger 2011.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 302.

- ^ Calloway 2014, pp. 117–122.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 306–309.

- ^ Sugden 2000, pp. 122–127.

- ^ a b c d e Gaff 2004.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 316–318.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 320.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 329-334.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, p. 335.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 338–341.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 359–361.

- ^ Butts 2011, p. 179.

- ^ Butts 2011, p. 230.

- ^ Hoffman 2009, pp. 375–381.

- ^ Pect 1904, p. 76.

- ^ Catalono 2015, pp. 78–82.

- ^ Schock 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Goodfellow 2007.

- ^ Calloway 1989.

- ^ Hoffman 2009.

- ^ a b c Butts 2011.

- ^ Benét, Stephen Vincent (24 October 1936). "The Devil and Daniel Webster". Saturday Evening Post.

- ^ "Trumpet in the Land". Retrieved 25 July 2025.

- ^ Clark, Todd Tamanend (2002). "Simon Girty's Decision." Staff Mask Rattle. Portland, Oregon: CD Baby.

References

- Barr, Daniel P. (1998). "'A Monster So Brutal'—Simon Girty and the Degenerative Myth of the American Frontier, 1783-1900". Essays in History. 40. Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia. Retrieved 2 November 2024.

- Brown, Parker B. (1987). "The Historical Accuracy of the Captivity Narrative of Doctor John Knight". The Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 70 (1): 53–67.

- Brackenridge, Hugh Henry (1783). Narratives of a Late Expedition against the Indians: With an Account of the Barbarous Execution of Col. Crawford; and the Wonderful Escape of Dr. Knight and John Slover from Captivity, in 1872. Philadelphia: Francis Bailey.

- Buffenbarger, Thomas E. (2011). "St. Clair's Campaign of 1791: A Defeat in the Wilderness That Helped Forge Today's U.S. Army". United States Army.

- Butterfield, Consul Willshire (1890). History of the Girtys: Being a Concise Account of the Girty Brothers—Thomas, Simon, James and George—and of their Half-Brother, John Turner. Cincinnati, Ohio: Robert Clark & Co.

- Butts, Edward (2011). Simon Girty: Wilderness Warrior. Toronto: Dundurn. ISBN 978-1459700758.

- Calloway, Colin G. (1989). "Simon Girty: Interpreter and Intermediary". In Clifton, James A. (ed.). Being and Becoming Indian: Biographical Studies of North American Frontiers. Chicago: Dorsey. pp. 38–58.

- Calloway, Colin G. (2014). The Victory with No Name: The Native American Defeat of the First American Army. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199387991.

- Gaff, Alan D. Bayonets in the Wilderness: Anthony Wayne's Legion in the Old Northwest. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Hoffman, Phillip W. (2009). Simon Girty: Turncoat Hero: The Most Hated Man on the Early American Frontier. Franklin, Tennessee: Flying Camp Press. ISBN 978-0984225637.

- Kelsay, Isabel Thompson (1984). Joseph Brant, 1743-1807: Man of Two Worlds. Syracuse, New York: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815601821.

- Leighton, Douglas (1983). "Simon Girty". Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online.

- Mahan, Russell (2020). The Kentucky Kidnappings and Death March: The Revolutionary War at Ruddell's Fort and Martin's Station. West Haven, Utah: Historical Enterprises. ISBN 978-1735644608.

- Schenawolf, Harry (2015). "Lord Dunmore: Last Royal Governor of Virginia and the First to Offer Slaves Their Freedom". Revolutionary War Journal. Retrieved 6 June 2025.

- Schoenbrunn Amphitheatre Box Office (31 October 2018). "Paul Green's Trumpet in the Land". trumpetintheland.com. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Schock, Mark P. (2006). "Sympathy for the Devil: Simon Girty, the Frontier Captive Experience, Loyalty and American Memory". Fairmount Folio Journal of History. 8. Wichita State University: 15–27.

- Sterner, Eric (2018). "General Edward Hand: The Squaw Campaign". Emerging Revolutionary War Era. Retrieved 11 June 2025.

- Sterner, Eric (2019). "The Siege of Fort Laurens, 1778–1779". Journal of the American Revolution. Retrieved 14 June 2025.

- Sterner, Eric (2023). The Battle of Upper Sandusky, 1782. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme. ISBN 978-1594164019.

- Sugden, John (2000). Blue Jacket: Warrior of the Shawnees. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0803242883.

- Sword, Wiley (1985). President Washington's Indian War: The Struggle for the Old Northwest, 1790-1795. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806118644.

- Werther, Richard J. (2023). "The 'Western Forts' of the 1783 Treaty of Paris". Journal of the American Revolution.

- White, Richard (1991). The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650-1815. Cambridge Univeristy Press. ISBN 0521424607.

- Williams, Glenn F. (2017). Dunmore's War: The Last Conflict of America's Colonial Era. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing.

- Williams, Glenn F. (2024). "Lord Dunmore's War". Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Humanities. Retrieved 9 June 2025.