Shuihu

A shuihu or shui hu (Chinese: 水虎; pinyin: shuǐhǔ; Wade–Giles: shui-hu; Japanese pronunciation: suiko; lit. 'water tiger'),[b] is a legendary creature said to have inhabited river systems in what is now Hubei Province, China.

Overview

The name shuihu (or suiko) derives from the creature possessing physical characteristics reminiscent of a tiger (虎, Chinese pronunciation: hu; Japanese: ko/tora).

The water tiger is described as similar (in size) to a 3 or 4-year old human child, with tiger-like head and lower limb, and covered with tough scales resisting arrows. It basks on sandbars, while keeping their claws submerged in water. If a human tries to tamper with he may be killed.

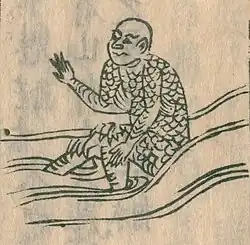

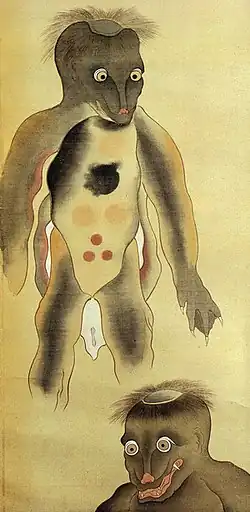

Japanese books during the Tokugawa Period read the Chinese text rather differently. Wakan Sansai Zue, an influential encyclopedia of the early 18th-century, gave a considerably divergent reading and stated that the suiko possessed kneecaps like tiger-claws. This odd feature was replicated in its woodcut illustration, and propagated in Toriyama Sekien's drawing of the suiko in his yōkai anthology.

Though the Wakan Sansai Zue considered the shuihu / suiko to be a creature similar to, but distinguished from the kawatarō (more commonly known as kappa, other works during the Edo period commonly used the sinitic term suiko as a synonym of kappa.

Past Japanese writers also sometimes used suiko (水虎; 'water tiger') as a stilted Sinitic term for the kappa (also kawatarō) in native folklore, even though Wakan Sansai Zue had distinguished these as two separate beings.

General description

The shuihu or shui hu[c] (Chinese: 水虎, 'water tiger') is described as being "about the size of a three- or four-year old (human) child", with a head like a tiger's,[8][5][4][d] and a shell like that of the pangolin.[4][e] Their knees, which are also tiger-like, may be visible above water, but their claws always remain submerged, despite their habit of lying on sandy riverbanks and basking in the sun in autumn.[4][f]

Information about the Suiko became widely known through its inclusion in the Ming Dynasty pharmacopoeia, the Bencao gangmu (Compendium of Materia Medica; specifically volume 42 of the Siku Quanshu edition). The description quotes the original source Xiang mian ji (襄沔記, 'Records of Xiang Mian'; 8th century).[13][4] A similar description can be found in the 6th-century Commentary on the Water Classic[g] as quoted in the 17th century Ming Period dictionary, Tongya, where it is stated that the shuihu is also known as shuǐtáng (水唐) or shuǐlú (水盧);[14][15] however, the form shuǐtáng may be unique to the Tongya.[16]

Alternative reading

The description of the suiko in the Bencao Gangmu has been interpreted quite differently in Japan. In the past, a dissident reading was given for the passage in the Chinese source Bencao Gangmu, particularly among Japanese sources. The Osaka physician Terashima Ryōan, in his Wakan Sansai Zue (1712), interpreted the text to read "its knee-cap resembles that of a tiger's forepaw claws",[17] and this reading has persisted in Japanese literature on the suiko into the present-day.[18][19][20]

The accompanying woodcut in the Wakan Sansai Zue (figure top right)[17] illustrated this (the tiger-claw kneecap) as well. The artist Toriyama Sekien, who consulted Terashima's encyclopedia,[21] also drew the creature with the claws on the knees, with the caption: "..its kneecaps are sharp like tiger claws".[1]

Geography

According to the quote from the Xiang mian ji, the shuihu inhabits the confluence where the river Shu (涑水)[h] meets the river Mian (沔水)[4] (now known as the Han River[23]) in Zhonglu County,[i] in today's Xiangzhou District, Hubei Province.

Pharmacological use

The original text found in the Bencao Gangmu states that, if the shuihu is caught alive, then the harvested nose can be "used for some trifles".[4] The part of the anatomy in question is not referred to as the nose (鼻, bí) but as the bíyàn (simplified Chinese: 鼻厌; traditional Chinese: 鼻厭) in the Tongya text,[j] further explained to be the yīn (陰) or the "force" (Chinese: 勢, shì) of the beast.[14][15] In reference to the shuihu, the harvest of this body part has been glossed as "castration",[26] namely, the removal of its genitals, as one newspaper has more bluntly put it.[27][k] It is also stated that the part can be applied as an aphrodisiac (媚藥, mèiyào).[14]

Trifle use

The term xiaoshi (小使), which has been literally rendered as "used for some trifles" in translation,[4] actually refers to some aspect of sexuality or reproduction (bodily fluid), according to sources. More specifically, this term xiaoshi (lit. 'small use') is glossed as a synonym of xiaotong (小通, lit. 'small avenue/path') in the Zhengzitong (正字通, Zhèngzìtōng) dictionary, among other sources, and one instance of the usage of "small avenue" occurs in a poem in the Han shi waizhuan, where it is sung that the male's "small avenue" reaches sexual maturity at age 16, and the female's at age 14.[l][m][15][30]

Taming

There are alternative interpretations, where instead of pharmacological use, the live specimen becomes a tamed or trained beast with the removal or manipulation of the body part.

One interpretation of the statement is that, when the genitals are removed from the beast, it becomes tame or docile, much like the spaying or neutering of dogs and cats.[27] The Wakan Sansai Zue interpreted this passage of Chinese text to mean that if a person pinches (摘まむ, tsumamu) the nose, the beast turns into a servant (小使, kozukai).[n][17]

Suiko in Japan

The Japanese interpretation of the suiko according to their reading of the Chinese pharmacopeia was already discussed above (§ Alternative reading).

Distinguished from kappa

Terashima Ryōan in his 18th century Wakan Sansai Zue stated that the suiko was similar to the kawatarō (western name for kappa[31][33][o]), but differing from it. Thus thus Ryōan demarcated the suiko and kawatarō entries as separate (though adjacent).[17][34]

The artist Sekien, who followed after this encyclopedia,[21] also illustrated the two creatures separately.[35][p]

Earlier, Kaibara Ekken in his Yamato honzō (大和本草) (pub. 1709) had distinguished the kappa/kawatarō and the suiko as "mutually similar but not the same",[36][37] and the Wakan Sansai Zue followed that path.[38]

An awareness of the differences is also demonstrated by Ono Ranzan in his Honzō Kōmoku Keimō (本草綱目啓蒙, Enlightenment on the Compendium of Materia Medica).[39] Ranzan primarily describes the Japanese kappa (love of sumo is obviously Japanese) in the main text, while relegating quoted information about the Chinese Suiko to footnotes.[15][40]

As synonym for kappa

But in Japan, the word suiko (shuihu) was frequently also used as synonym for kappa.[41][35] even though it is far from clear if the shuihu of China and the kappa of Japan can be regarded as sharing a common origin.[41]

Examples of synonymous treatment can be found in the physician Kurokawa Dōyū's Enpekiken ki (遠碧軒記)[42] or Yamazaki Yoshinaris Sanyō zakki (三養雑記).[43]

A number of literature on the kappa bearing suiko in the title also appeared that included paintings of allegedly captured kappa such as:[44][45]

- Suiko-no-zu (水虎之図; lit. "Suiko Diagram", Kansei to Tenpō era/1789–1830)

- Suiko setsu (水虎説; lit. "Discourse on the Suiko"; A Study of Water Tigers c. Bunsei 3・1820)

- Suiko kōryaku (水虎考略; lit. "Brief Study of the suiko", Bunsei 3/1820; copy made Tenpō 7/1836).[6]

- Suiko jūnihin no zu (水虎十二品之図; lit. "Illustration of 12 specimens of suiko", first pub. c. 1850?).[46][47][q]

Similarly, the sections "Ōmi Suiko-go / Hizen Suiko-go" (Tales of the Suiko of Ōmi / Hizen) in Yanagihara Norimitsu's Kansō Jigo (閑窓自語)[48] simply use the kanji "水虎" (Suiko) to refer to the Kappa of Lake Biwa and Kyushu.

This usage can even be found in the folklore collected in the modern day from various regions, including Tōhoku and Kyushu. The Suijin worship known as Suiko-sama) found in Aomori Prefecture is another example of the term's repurposed usage.[49]

In parts of Aomori Prefecture, the kappa have been deified and enshrined by the name of suiko-sama.[50]

See also

- Kappa (folklore)

- Enkō (folklore)

- Kenmun

Notes

- ^ The accompanying text reads: "Suiko is shaped like a child. Its carapace resembles that of a pangolin, and its kneecaps are sharp like tiger claws. It dwells in China's Sushui River, where it is often seen on the sand, drying its shell".[1] The carapace/shell (甲) is described as like those of a 綾鯉 (pangolin)[2] which would normally be read with the on'yomi reading ryōri,[3] but Toriyama here forces the reading of senzankō,[2] the modern-day common term for pangolin in Japan.

- ^ Unschuld translates in two words, shui hu.[4] The hyphenated form shui-hu adheres to the Wade-Giles system, used by Strassberg for example.[5]

- ^ The Unschuld translation uses the form shui hu.[4] The form shuihu is employed by a Japanologist[6] and a Sinologist, though the latter concerns shuihu that dwell in the human body and "like to eat mercury".[7]

- ^ Literally it only actually states "resembling children aged three to four years" in the Bencao Gangmu,[4] but the extrapolation has been made that this concerns the size[5] or "being shaped like a child".[9]

- ^ The Bencao gangmu in its entry for shuihu refers to the pangolin as the 綾鯉 (línglǐ),[8][4][10] which literally can be translated to mean "hill carp".[11] This explains why it is stated as "carp" rather than "pangolin" in one translated paper.[9] The Bencao gangmu has its own entry on the 綾鯉 (línglǐ), where it is noted that the beast is also known as 穿山甲 (chuānshānjiǎ,[12] pronounced senzankō in Japanese,[3] which is the common modern term. The Kō yamato honzō (広大和本草) forcibly reads "鯪鯉 as senzankō, while the illustrator Sekien used the form 綾鯉 (línglǐ, ryōri) also forcibly read as senzankō).

- ^ Unschuld parses (punctuates) the text as "膝頭似虎,掌爪..", "Their knees and their heads resemble those of tigers; their claws" (whereas past Japanese scholarship decided their "knee-heads (knee-caps) resembled tiger-forepaw-claws", cf. infra.). Unschuld did not bother to distinguish forepaw-claw.

- ^ simplified Chinese: 水经注; traditional Chinese: 水經注; pinyin: Shuǐ Jīng Zhù.

- ^ The identity of the River Shu here is uncertain.[22] There is a river Shu mentioned in the Commentary on the Water Classic but that likely different, since that river is situated in Wenxi County in what is now Shanxi Province.

- ^ simplified Chinese: 中庐县; traditional Chinese: 中廬縣; pinyin: Zhōnglú Xiàn.

- ^ Also written as gāoyàn (simplified Chinese: 皋厌; traditional Chinese: 皋厭) in the unrectified text.[24]

- ^ It is not an obscure reference that the term yīn (陰) could imply or denote the genitalia, and it is one of the dictionary definitions,[28] but the term yīn (as in yin-yang) carries a variety of meanings.

- ^ As pointed out in Ono Ranzan's commentary on the shuihu. The same gloss (indication of synonym), and poem example also occurs in the Tongya, though in another book not specifically connected with the shuihu.

- ^ In an English translation of this poem, the male's "small avenue" is rendered as "semen", and the female's as "her [bodily] fluids".[29]

- ^ The historical kana" given in the original is コツカヒ"; the modern form is "コヅカイ".

- ^ Terashima Ryōan was a physician based in Osaka, and he uses the term kawatarō (川太郎; かハたらう).[17]

- ^ "Although [suiko] is often treated as a variation of the kappa, Sekien breaks it out into its own entry here".[1]

- ^ Expanded after Suiko kōryaku and other sources.[47]

References

- Citations

- ^ a b c d Toriyama, Sekien (2017), Japandemonium Illustrated: The Yokai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien, translated by Hiroko Yoda; Matt Alt, Courier Dover Publications, p. 91, ISBN 9780486818757

- ^ a b Toriyama, Sekien (1779), Konjaku gazu zoku hyakki 今昔画図続百鬼, hdl:2324/422771, Kyushu University Library Collections.

- ^ a b Suzuki tr. (1930). p. 361

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Unschuld tr. (2021), p. 499.

- ^ a b c Strassberg, Richard E. (1994). Inscribed Landscapes: Travel Writing from Imperial China. University of California Press. p. 445, endnote 10. ISBN 9780520914865.

- ^ a b Marcon, Federico (2015). The Knowledge of Nature and the Nature of Knowledge in Early Modern Japan. University of Chicago Press. p. 195. ISBN 9780226251905.

- ^ Baldrian-Hussein, Farzeen (2004). "The Book of the Yellow Court: A Lost Song Commentary of the 12th Century". Cahiers d'Extrême-Asie. 14: 216. doi:10.3406/asie.2004.1207. ISBN 9782855396408. JSTOR 44160396.

- ^ a b Li Shizhen (1596) "Bugs (Worms, Insects, Amphibians) 4"; Li Shizhen (1782) Book 42, "Bugs 4". The Chinese text is also printed side by side in the Unschuld translation.

- ^ a b Ishida, Eiichirô; Yoshida, Ken'ichi (1950). "The Kappa Legend: A Comparative Ethnological Study on the Japanese Water-Spirit "Kappa" and Its Habit of Trying to Lure Horses into the Water" (PDF). Folklore Studies. 9: 119–120. doi:10.2307/1177401. JSTOR 1177401.

- ^ Unschuld, Paul U.; Zheng, Jinsheng (2021). "Section Worms/Bugs. Chapter 42. Appendix. Shui hu". Chinese Traditional Healing (3 vols): The Berlin Collections of Manuscript Volumes from the 16th through the Early 20th Century. BRILL. p. 333. ISBN 9789004229099.

- ^ Totton, Mary-Louise (2002). Weaving Flesh and Blood Into Sacred Architecture: Ornamental Stories of Candi Loro Jonggrang. University of Michigan. p. 65. ISBN 9780493736860.

- ^ Nappi, Carla (2010). The Monkey and the Inkpot: natural history and its transformations in early modern China. Harvard University Press. pp. 35, 174 n9, 209. ISBN 9780674054356.

- ^ Li Shizhen (1782). Bencao Gangmu (Siku Quanshu library edition): 本草綱目 (四庫全書本)「巻42 蟲之四 溪鬼蟲〈拾遺〉水虎」:"時珍曰襄沔記云中廬縣有涑水注沔中有物如三四嵗小兒甲如鱗鯉射不能入秋曝沙上膝頭似虎掌爪常没水出膝示人小兒弄之便咬人人生得者摘其鼻可小小使之名曰水虎". The (misprinted) word for pangolin, 鱗鯉, in this edition occurs as 鯪鯉 in the 1596 edition, and the latter is the form given by Unschuld.

- ^ a b c Fang Yizhi [in Chinese], Tongya 通雅 (in Chinese), vol. 47, ¶38

- ^ a b c d Ono, Ranzan (1844), Ono, Mototaka (ed.), Jūshū honzō kōmoku keimō (in 35 vols.) 重修本草綱目啓蒙 (in Japanese), vol. 28, Hishiya Kichibē, pp. 18b – 20a. (copy held at NDL)

- ^ Asakawa Zen'an Zen'an zuihitsu 善庵随筆, via Kojiruien (1930) Dobutsu-bu/kemono 7 (e-text)

- ^ a b c d e Terashima Ryōan [in Japanese] (n.d.) [1712], "40. Gūrui & kairui: Suiko" 四十 寓類・怪類:水虎, Wakan Sansai zue 和漢三才図会, vol. 27, Book 40 (kan-no-40), fol. 17b–18a

- ^ Higashi Mutei (1920), Kokubu, Takatane [in Japanese]; Ikeda, Shirōjirō [in Japanese] (eds.), "So'utei zuihitsu" 鉏雨亭随筆, Nihon shiwa sōsho 日本詩話叢書 (in Japanese), vol. 5, Bunkai-dō Shoten, pp. 292–293

- ^ Ishikawa Jun'ichirō [in Japanese] (1985). Shinpan Kappa no Sekai (New Edition: The World of the Kappa) (in Japanese). Jiji Tsūshin Shuppankyoku. pp. 52–53. ISBN 9784788785151.

- ^ Ozawa (2011), pp. 31–32

- ^ a b "Suiko, Water-Tiger.. His illustration is new but the description paraphrases the one in the Illustrated Sino-Japanese Encyclopedia of the Three Realms [=Wakan sansai zue]".[1]

- ^ Suzuki tr. (1930), p. 324 n2.

- ^ Zhang, Zhibin; Unschuld, Paul Ulrich, eds. (2015), Dictionary of the Ben Cao Gang Mu, Volume 2: Geographical and Administrative Designations, Univ of California Press, p. 218, ISBN 9780520291966

- ^ Fang Yizhi [in Chinese] (1805), Yao Wenxie [in Chinese] (ed.), Tongya 通雅 (in Chinese), vol. 47, Kuwana, Japan, p. 19b–20a

- ^ Jang Dobin 張道斌 [in Korean]; Gwon Sangro 權相老 [in Korean], eds. (1982), Gosa seongeo sajeon (고사성어사전) 故事成語辭典, Hakwonsa, p. 528

- ^ "Removing gāoyàn which is castration 摘皋厭은 勢去".[25]

- ^ a b "Jiuzhou yaoguai lu:shuihu" 九州妖怪录│ 水虎 [Records of the Nine Provinces' monsters: shuihu]. Tencent Newspaper 腾讯新聞. 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2021-07-03.

- ^ Thoms, P. P. (1819), A dictionary of the Chinese language, in three parts, p. 1029

- ^ Han Ying [in Chinese] (1952). Han Shih Wai Chuan: Han Ying's Illustrations of the Didactic Application of the Classic of Songs. Translated by Hightower, James Robert. Harvard University Press. p. 28.

- ^ Fang Yizhi. Tongya 18. ¶46; Fang Yizhi (1800) unpaginated; Fang Yizhi (1805) 18, pp. 13b–14a.

- ^ a b Ozawa (2011), pp. 27–28.

- ^ Miyamoto, Mataji [in Japanese] (1970). Fūzokushi no kenkyū & Kōnoike-ke no kenkyū 風俗史の研究・鴻池家の研究. Osaka no kenkyū 5 (in Japanese). Seibundō shuppan. p. 230.

- ^ The Butsurui shōko (1775) explains that kawatarō, or so the creature is known in either Kinai (part of modern Kansai) or Kyūshū, is known as kappa in the east, and this is a truncated form of kawa-wappa.[31] Cf. local historian Prof. Mataji Miyamoto who states that what was called kappa in Edo was called gatarō (河太郎; がたろう) in Osaka.[32]

- ^ Ozawa (2011), pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b Iwai, Hiromi [in Japanese], ed. (April 2000). Mizu no yōkai 水の妖怪. Kawade Shobō Shinsha. p. 14. ISBN 9784309613826.

水虎は河童の呼び方の一つとするのが一般的だが、石燕は、河童とは違う妖怪と考えていたようだ [The suiko is generally considered to be another name for kappa, but Sekien seemed to think it was a separate yōkai from the kappa.]

- ^ Kaibara Ekken (1709), "kappa (kawatarō)" 河童 (かはたらう), Yamato honzō 大和本草, Kyoto: Nagata Chōbei, Kan16, fol. 11

- ^ Nakamura, Teiri [in Japanese] (1996). "貝原"+"水虎" Kappa no nihonshi 河童の日本史. Japan Editors School. p. 183. ISBN 9784888882484.

- ^ Nakamura, Teiri [in Japanese] (January 1995). "Kappa denshō ni okeru jinteki yōso" 河童伝承における人的要素 [Man-like Characters in 'Kappa (a water spirit)' of Japanese Folklore]. 国立歴史民俗博物館研究報告 [Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History]. 61: 101.

- ^ Ono Ranzan, 『本草綱目啓蒙』(Honzō Kōmoku Keimō), vol. 3, Heibonsha (Tōyō Bunko), 1991, pp. 183-184.

- ^ Ozawa (2011), p. 28.

- ^ a b Suzuki tr. (1930), p. 324 n1. Annotation attributed to Yano. probably entomologist {Yano Munemoto, since this is the "Bugs" section of the work.

- ^ Nihon Zuihitsu Taisei 日本随筆大成, 1st series, vol. 10, Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, 1975, p. 117.

- ^ Nihon Zuihitsu Taisei 日本随筆大成, 2nd series, vol. 6, oshikawa Kōbunkan, 1974, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Takagi Shunzan (1988). Edo Hakubutsu Zukan 2: Honzō Zusetsu Suisan 江戸博物図鑑2 本草図説 水産. Libro Port. pp. 98–100.

- ^ Bessatsu Taiyō: Nihon no yōkai 別冊太陽 日本の妖怪. Heibonsha. 1987. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-4-582-92057-4.

- ^ Suiko jūnihin no zu 虎十弐品之圖, Illustrated (copied as miniatures) by Sakamoto Juntaku, 林奎文房, ndljp:254303

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b "Egakareta dōbutsu shokubutsu: Edo jidai no hakubutsushi. Chapter 3. Chinkin kijū igyo: egakareta dōbutsu shokubutsu" 描かれた動物・植物―江戸時代の博物誌:第3章 珍禽奇獣異魚 - 描かれた動物・植物 [Depicted fauna and flora: Edo period natural history. Chapter 3. Rara avis, mammalian marvels, queer fish]. National Diet Library. 2005. Retrieved 2012-06-10.

- ^ Yanagihara Norimitsu [in Japanese] (1974), "Kansō jigo" 閑窓自語, Nihon Zuihitsu Taisei 日本随筆大成, 2nd series, vol. 8, Yoshikawa Kōbunkan, pp. 297–298

- ^ Murakami, Kenji [in Japanese] (2000), Yōkai jiten 妖怪事典 (in Japanese), Mainichi Shimbunsha, p. 196, ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0

- ^ "Kappa densetsu: shinkakuka no rūtsu wo tadoru Aomori" 河童伝説: 神格化のルーツたどる 青森. Mainichi Shimbun (in Japanese). 2016-04-02.

- Bibliography

- Ozawa, Hana (March 2011), "Kappa no imēji no hensen ni tsuite: zushō shiryō no bunseki wo chūshin ni" 「河童」のイメージの変遷について―図像資料の分析を中心に― [Charting the Changing Image of the Kappa through Visual Representations] (PDF), Jomin bunka (in Japanese) (34): 23–46

- 神宮司庁 (1930), 動物部/獸七: 河童, in Jingū shichō (ed.), Koji ruien 古事類苑, vol. 49, Koji ruien kankōkai, pp. 480–490, doi:10.11501/1874269

- Li Shizhen (1596). . Bencao Gangmu 本草綱目 – via Wikisource.

- Li Shizhen (1782) [1596]. . Bencao Gangmu (SKQS) 本草綱目 (四庫全書本)』 – via Wikisource.

- Li Shizhen (1930). "Mushi-bu dai-42-kan furoku suiko" 蟲部第四十二卷 附録 水虎. Tōchū kokuyaku honzō kōmoku 頭註国訳本草綱目 (in Japanese). Vol. 10. Translated by Suzuki, Shikai. Shunyōdō. pp. 323–324.

- Li Shizhen (2021). "Section Worms/Bugs. Chapter 42. Appendix. Shui hu". Ben Cao Gang Mu, Volume VIII: Clothes, Utensils, Worms, Insects, Amphibians, Animals with Scales, Animals with Shells. Translated by Paul U. Unschuld. Univ of California Press. p. 499. ISBN 9780520976986.

External links

- "Dōbutsu-bu/jū 7" 動物部/獸七. Kojiruien database 故事類苑データベース. International Research Center for Japanese Studies. 2019-11-13. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- yabtyan (2010-03-02). "Wakan sansai zue kan dai 40" 和漢三才圖會卷第四十. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- 日本妖怪河童VS中國的水虎,信不信你會把它們認錯哦! [Japanese monster kappa vs. Chinese water tiger, believe it or not, you will mistake them for each other!]. Meiri toutiao/Daily Headlines/KK News 每日頭條. 2017-07-03. - illustration