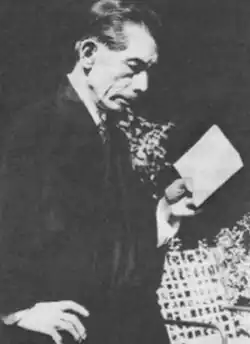

Setsuzo Kotsuji

Abraham Setsuzō Kotsuji | |

|---|---|

| 小辻 節三 | |

| |

| Born | Setsuzō Kotsuji 1899 Kyoto, Japan |

| Died | 31 October 1973 United States |

| Other names | Abraham |

| Occupation(s) | Hebraist; scholar; writer |

| Known for | Aid to Jewish refugees in Japan; public stance against antisemitism; conversion to Judaism |

Abraham Setsuzō Kotsuji (小辻 節三, Kotsuji Setsuzō; 1899, Kyoto – 31 October 1973) was a Japanese Orientalist and Hebraist, the son of a Shinto priest from a long line of priests. During the Holocaust he assisted Jewish refugees—first in Kobe and later in Japanese-occupied Shanghai—and spoke out against Nazi-inspired anti-Jewish propaganda.[1] A Japanese-language biography about his aid to refugees was written by actor Jundai Yamada and published in 2013 by NHK Shuppan.[2]

He converted to Judaism in 1959, having earlier converted from Shinto to Christianity in his youth.[3] In his memoir From Tokyo to Jerusalem he described his religious journey and lifelong engagement with Hebrew and the Bible.

He first encountered Jews while working for the South Manchuria Railroad Company during World War II.

Early life and education

Kotsuji was born in Kyoto to an aristocratic Shinto family; his father was a kannushi (Shinto priest). As a teenager he read a Japanese translation of the Bible, which led him to monotheism and study with Christian missionaries; he converted to Presbyterian Christianity and began studying Hebrew. He later pursued philological studies in the United States and completed a doctorate in Hebrew and Jewish studies at Kyoto University.[4][5]

Hebraist and academic activity

In 1937 he published a major work on Hebrew language and grammar and founded a faculty for Bible and Hebrew studies at a Tokyo university, attracting many students and becoming a leading Japanese authority on Hebrew. He also tutored Prince Mikasa, the younger brother of Emperor Hirohito.[4]

Following Japan’s occupation of Manchuria and the establishment of Manchukuo, Kotsuji was appointed an adviser on “Jewish affairs” and sent to Harbin, where he developed close relations with the Jewish community and its chief rabbi, Aharon Moshe Kisilev.[4]

Aid to Jewish refugees in Kobe and Shanghai

Between July 1940 and September 1941 more than 4,600 Jewish refugees—many holding Sugihara transit visas—arrived in Kobe, including the entire Mir Yeshiva contingent of about 300 students. Seeing that their visas were expiring within weeks, Kotsuji used his relationship with Foreign Minister Yōsuke Matsuoka to help extend stays in Kobe; he also mediated between refugee leaders and Japanese authorities and helped arrange the community’s eventual transfer to Shanghai under Japanese occupation.[6]

Public stance against antisemitism and wartime arrest

As antisemitic agitation grew in wartime Japan under German influence, Kotsuji lectured across the country and wrote to counter slanders, describing Jews as an ethical and upright people and calling on Japanese audiences to offer refuge. In late 1942 he was arrested by investigative authorities on suspicion of aiding “enemies of Japan”—i.e., Jews—and interrogated about a supposed “Jewish world conspiracy.” He was released after a senior army officer who knew him intervened. The episode strengthened his conviction in defending Jews.[4][7]

Conversion to Judaism and later life

In October 1959, during a visit to Israel, Kotsuji underwent circumcision and converted to Judaism in Jerusalem, with the encouragement of Rabbi Dr. Zerach Warhaftig. Members of the Mir Yeshiva organized a welcome reception led by R. Chaim Shmuelevitz. He later lived for a period in Brooklyn, where the Jewish community assisted him as his health declined. His memoir From Tokyo to Jerusalem appeared in 1964.[5][4]

Death and legacy

Kotsuji died in the United States on 31 October 1973 and, per his will, was buried at Har HaMenuchot in Jerusalem. His efforts on behalf of refugees and his opposition to antisemitism have been commemorated in research and public events.[6][4] A contemporary obituary appeared in The New York Times on 18 November 1973.[8]

Recognition

In Israel, Kotsuji’s actions on behalf of Jewish refugees have been remembered with appreciation. Former Deputy speaker of Knesset and head of the Israel-Japan Parliamentary Friendship Group Zvi Hauser stated:

Kotsuji showed rare public courage in standing up against antisemitism in wartime Japan, and worked to aid the thousands of Jewish refugees who found themselves in Kobe. His legacy demonstrates how an individual, even without official authority, can make a decisive difference in the fate of others.

— Zvi Hauser, [9]

Works

- The Origin and Evolution of the Semitic Alphabets. Tokyo: Kyo Bun Kwan, 1937.[4]

- From Tokyo to Jerusalem. New York: B. Geis Associates (distributed by Random House), 1964.[5]

See also

References

- ^ Sofer, D. (20 November 2004). "The Japanese Convert". Aish.com. Aish HaTorah. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ 命のビザを繋いだ男―小辻節三とユダヤ難民。山田 純大 (著) "Inochi no biza wo tsunaida otoko – Kotsuji Setsuzō". ISBN 978-4140815991

- ^ Time magazine (archived)

- ^ a b c d e f g Medzini, Meron (2016). Under the Shadow of the Rising Sun: Japan and the Jews during the Holocaust Era. Routledge. ISBN 9781138803373.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ a b c Kotsuji, Abraham Setsuzo (1964). From Tokyo to Jerusalem. New York: B. Geis Associates.

- ^ a b "After Sugihara: Setsuzo Kotsuji's Aid to Jewish Refugees". Consulate General of Japan in Los Angeles. 8 April 2019. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Schwarcz, Vera (2018). "Respite in Japan". In the Crook of the Rock: Jewish Refuge in a World Gone Mad — The Chaya Leah Walkin Story. Academic Studies Press: 53–78. doi:10.1515/9781618117878-006. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ "Dr. Abraham Kotsuji, Hebraist, Scholar and Writer, Dies". The New York Times. 18 November 1973. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- ^ Hauser, Zvi (28 October 2020). "Persona non grata no more: Chiune Sugihara". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

Further reading

- Medzini, Meron (2024). "Japan's Jewish Policy during the Pacific War, 1941–1945". Japan, the Jews, and Israel: Similarities and Contrasts. De Gruyter Oldenbourg: 74–115. doi:10.1515/9783111239781-010. Retrieved 17 August 2025.

- Yamada, Jundai (2013). 命のビザを繫いだ男—小辻節三とユダヤ難民 (A Man Who Connected the “Visas for Life”: Setsuzō Kotsuji and the Jewish Refugees) (in Japanese). NHK Shuppan.