Kingdom of Serbia (1718–1739)

Kingdom of Serbia | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1718–1739 | |||||||||

Kingdom of Serbia (1718–1739) | |||||||||

| Status | Crownland of the Habsburg monarchy | ||||||||

| Capital | Belgrade | ||||||||

| Common languages | Serbian, German | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic, Serbian Orthodox | ||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||

• 1718–1720 | Johann O'Dwyer | ||||||||

• 1738–1739 | George de Wallis | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern period | ||||||||

| 21 July 1718 | |||||||||

| 1737–39 | |||||||||

| 18 September 1739 | |||||||||

| Currency | Kreuzer | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Serbia | ||||||||

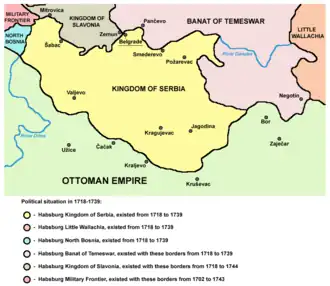

The Kingdom of Serbia (Serbian: Краљевина Србија, romanized: Kraljevina Srbija, German: Königreich Serbien, Latin: Regnum Serviae) was a province (crownland) of the Habsburg monarchy from 1718 to 1739. It was formed from the territories to the south of the rivers Sava and Danube, corresponding approximately to the Sanjak of Smederevo, an Ottoman province that was conquered by the Habsburgs in 1717, during the Habsburg-Ottoman war (1716–1718). The Kingdom existed until the next Habsburg-Ottoman War (1737-1739), when it was returned to the Ottoman rule in 1739.[1]

During the Habsburg rule, Serbian majority did benefit from self-government, including an autonomous militia, and economic integration with the Habsburg monarchy - reforms that contributed to the growth of the Serb middle class and continued by the Ottomans "in the interest of law and order".[2] Serbia's population increased rapidly from 270,000 to 400,000, but the decline of Habsburg power in the region provoked the second of the Great Migrations of the Serbs (1737–1739).

History

In 1688–1689, during the Great Turkish War, the Habsburg troops temporarily took control over most of present-day Serbia,[3] but were subsequently forced into retreat. The Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 recognized Ottoman authority over most of present-day Serbia, while the region of Bačka and the western part of Syrmia were assigned to the Habsburgs.

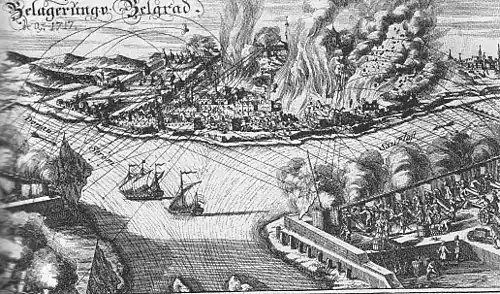

Another Austro-Turkish war broke out in 1716–1718,[4] in which Serbs massively joined the Habsburg troops. After the gains of 1718 (following the Treaty of Passarowitz), the Habsburgs sought to integrate Serbia into their empire. The land was officially named the "Kingdom of Serbia", because it was neither a part of the Holy Roman Empire nor the Kingdom of Hungary. The actual administration of the province was in the hands of an appointed governor. Not all the Serb-inhabited territory south of the Sava and Danube rivers that was conquered by the Habsburgs in 1718 was included in the Kingdom of Serbia. A large eastern area was administratively separate as part of the Banat of Temeswar.

During the Austro-Turkish War (1737–1739), the Habsburg monarchy lost all territories south of the Sava and Danube, including the whole territory of the Kingdom of Serbia, and Orșova north of the Danube. It retained, however, the rest of the Banat of Temeswar. The breakout of war and consequent end of Habsburg rule resulted in the second Great Migration of the Serbs (1737–1739).[5]

Government

Serbia was jointly supervised by the Aulic War Council and the Aulic Chamber, and subordinated to a local military-cameral administration.[6]

- Governors

- Johann Joseph Anton O'Dwyer (1718–1720) (known as "General Odijer")

- Charles Alexander (1720–1733)

- Karl Christoph von Schmettau (1733–1738)

- George Oliver de Wallis (1738–1739)

Serbian Militia

There was a portion of the Serbian peasant population that had a military obligation (and were not taxed as the rest of the agricultural population), known as the hajduks.[7] They formed the "Serbian national militia" that fought the Ottoman troops, and were exempt from tax in exchange for their military service, which included defending the borderlands, keeping peace, and maintaining and protecting the Great Road.[7] These hajduks constituted a privileged class in the kingdom, and received the most fertile lands for their settlements (which were separate from other villages) [7]

Economy

The economy of the Kingdom of Serbia was highly agricultural in nature and included viticulture, cereal farming, and livestock breeding, though none of these reached a substantial scale for large-scale export. Beekeeping, however, constituted one of the most economically important sectors in the kingdom, with the production and sale of honey and beeswax accounting for about one-third of tax revenue paid to Habsburg authorities. The government granted mining concessions to new joint-stock companies, including the Caesarea privilegiata Societas Commerciorum Orientalium, whose largest shareholders were Charles Alexander and his wife, the Orthodox Metropolitanate of Belgrade, and the urban German community of Belgrade as a whole. Projects were also undertaken to expand the forestry sector through reforestation of certain areas.[8]

Demographics

A 1720 regulation declared that Belgrade was to be settled mainly by Germans, while the Serbs were to live outside the city walls in the "Rascian" part.[6] It has been estimated that the population in Belgrade in the 1720s did not exceed 20,000.[6] The population increased rapidly from 270,000 to 400,000, but the end of Habsburg power in the region resulted in the second Great Serb Migration (1737–1739).[9]

Religious policies of Habsburg authorities towards various Christian communities were implemented by recognizing the Serbian Orthodox Metropolitanate of Belgrade, and also by establishing the Roman Catholic Diocese of Belgrade.[10][11]

Aftermath

Although the Habsburg administration over this part of present-day Serbia was short-lived, the consciousness about separate political entity was left behind by the Habsburgs, thus local inhabitants never again fully accepted Ottoman administration, which led to Koča's frontier rebellion in 1788 and to the First Serbian Uprising in 1804, that ended direct Ottoman rule over this part of present-day Serbia.[12]

References

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 151-154.

- ^ Hupchick 2004, p. 213.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 143.

- ^ Ágoston 2011, p. 93-108.

- ^ Ćirković 2004, p. 153-154.

- ^ a b c Hochedlinger 2013, p. 229.

- ^ a b c Rudi 2020, p. 150.

- ^ Rudi 2020.

- ^ Dabić 2011, p. 191-208.

- ^ Mitrović 2011, p. 209–217.

- ^ Točanac-Radović 2018, p. 155–167.

- ^ Nedeljković & Đorđević 2015, p. 23-37.

Sources

- Ágoston, Gábor (2011). "The Ottoman Wars and the Changing Balance of Power along the Danube in the Early Eighteenth Century". The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 93–108. ISBN 978-1-61249-195-0.

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Dabić, Vojin S. (2011). "The Habsburg-Ottoman War of 1716-1718 and Demographic Changes in the War-Afflicted Territories". The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 191–208. ISBN 978-1-61249-195-0.

- Hochedlinger, Michael (2013). Austria's Wars of Emergence: War, State and Society in the Habsburg Monarchy, 1683–1797. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-88793-5.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (2004). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-6417-5.

- Ingrao, Charles; Samardžić, Nikola; Pešalj, Jovan, eds. (2011). The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. ISBN 9781557535948.

- Mitrović, Katarina (2011). "The Peace of Passarowitz and the Re-establishment of the Catholic Diocesan Administration in Belgrade and Smederevo". The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 209–217.

- Nedeljković, Slaviša; Đorđević, Miloš (2015). "The Habsburg Monarchy and Serbs in the Ottoman Empire up Until the Congress of Vienna (1739-1815)" (PDF). Limes plus: Geopolitički časopis. 12 (3): 23–37. Archived from the original on 2020-07-12. Retrieved 2025-06-01.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Točanac-Radović, Isidora (2018). "Belgrade - Seat of the Archbishopric and Metropolitanate (1718–1739)". Belgrade 1521-1867. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 155–167. ISBN 978-86-7743-132-7.

Further reading

- Đorđević, Miloš Z. (2010). "A Background to Serbian Culture and Education in the First Half of the 18th Century according to Serbian Historiographical Sources". Empires and Peninsulas: Southeastern Europe between Karlowitz and the Peace of Adrianople, 1699–1829. Berlin: LIT Verlag. pp. 125–131. ISBN 978-3-643-10611-7.

- Heppner, Harald; Schanes, Daniela (2011). "The Impact of the Treaty of Passarowitz on the Habsburg Monarchy". The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 53–62.

- Karagöz, Hakan (2018). "The 1717 Siege of Belgrade and the Ottoman War Equipment Captured by the Habsburgs after the Siege". Belgrade: 1521-1867. Belgrade: The Institute of History. pp. 129–154. ISBN 978-86-7743-132-7.

- Langer, Joseph (1889). "Serbien unter der kaiserlichen Regierung : 1717 – 1739". Mittheilungen des k.k. Kriegsarchivs, Wien, Bd. III.

- Mrgić, Jelena (2011). "Tracking the mapmaker: The role of Marsigli's itineraries and surveys at Karlowitz and Passarowitz". The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 221–237.

- Pavlović, Dragoljub M. (1901). Austriska vladavina u Severnoj Srbiji od 1718-1739, po građi iz bečkih arhiva. Štamp. Kralj. Srbije.

- Rudi, Fabrizio (2020). "Austrian "Kingdom of Serbia" (1718- 1739). The Infrastructural Innovations introduced by the Habsburg Domination" (PDF). Yearbook of the Society for 18th Century Studies on South Eastern Europe: 142–153.

- Simić, Vladimir (2011). "Patriotism and Propaganda: Habsburg Media Promotion of the Peace Treaty of Passarowitz". The Peace of Passarowitz, 1718. West Lafayette: Purdue University Press. pp. 267–290.

- Stefanović-Vilovsky, Theodor von (1908). Belgrad unter der Regierung Kaiser Karls VI: (1717-1739) mit Benützung Archivalischer und Anderer Quellen. Holzhausen.

- Schwicker, Johann Heinrich (1881). "Die Vereinigung der serbischen Metropolien von Belgrad und Carlowitz im Jahre 1731". Archiv für österreichische Geschichte. 62: 305–450.

- Točanac-Radović, Isidora (2019). "Belgrade Under Habsburg Rule 1717-1739" (PDF). Baroque Belgrade: Transformation 1717-1739. Belgrade: Institute of Archaeology; Belgrade City Museum. pp. 12–37. Archived from the original on 2025-06-01. Retrieved 2025-06-01.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Točanac-Radović, Isidora (2022). "The Great Migration of Serbs and the Question of the Serbian Ethnic and Religious Community in the Habsburg Monarchy". Migrations in the Slavic Cultural Space: From the Middle Ages to the Present Day. Łódź: Łódź University Press. pp. 15–27.

External links

.svg.png)

.svg.png)