Second Battle of Tucson

| Second Battle of Tucson | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Apache-Mexico Wars | |||||||

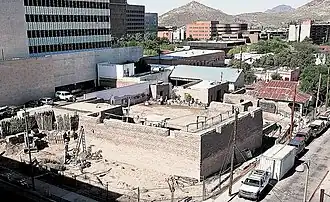

The reconstructed bastion of Fort Tucson, 2009. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Apache | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| Unknown | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

62 cavalry 10 native scouts ~1 artillery 1 fort | ~600 warriors | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

1 killed 3 wounded | 8–30 killed | ||||||

| Civilian Casualties: 1 killed | |||||||

The Second Battle of Tucson, or the May Day Attack, occurred in Tucson, Arizona, and the neighboring pueblo. It happened during the Mexican Apache Wars on May 1, 1782, between a small garrison of Spanish soldiers and hundreds of Apache warriors.

Background

Presidio San Augustin del Tucson, or Fort Tucson, was a Spanish built fortress located in present-day downtown Tucson, Hugh O'Conor founded it. The structure's construction occurred from 1775 to 1783 and was used to protect communication and trade routes across northern Sonora and southern Alta California. The garrison, on average, consisted of forty to sixty cavalry, mostly of Sonoran descent. Though detribalized Pima native American scouts were also employed. Fort Tucson was primarily made of adobe bricks and wood from mesquite trees. At least one cannon and only a few officers also manned the position. Tucson was an isolated community during its earliest years, situated on the right side of the Santa Cruz River, next to a Pima pueblo, known as Indian Town, on the left side of the water, roughly northwest of Tucson. A bridge led across the river between the village and the presidio.

The area around the presidio jacals was fortified with a wide ditch roundabout filled with water and a palisade of logs, ordered to be constructed by Commander Captain Pedro Allande y Saabedra, with two ramparts on which an unknown number of cannon were placed. Four bulwarks, magazines, a guard tower and a church were also built. The walls spanned various heights from ten to almost thirty feet high and were built to be compact. There were two gates, one on the eastern wall and the other on the western wall. A stockade and then an earthen defensive fence surrounded the military buildings. Some of the houses, belonging to Tucson citizens or soldiers, were outside the palisade and were protected only by artillery.

By 1782, the Spanish had been fighting a long war with the Apaches throughout Tucson. The garrison had already fought off an enemy attack in 1779, known as the First Battle of Tucson, at the edge of the town. In 1780, other small skirmishes between Spain and the Apaches occurred near Tucson. Apaches also conducted raids against wagon trains and other small unprotected convoys. However, Apache tactics changed in 1782 when they began to mass in larger numbers and attack heavily fortified or heavily protected settlements. A force of about 600 warriors headed for Tucson, retaliating for a recent Spanish campaign deep into Apache territory. After the battle, Captain Saabedra stated that the assault was carried out by the largest force of Apache warriors he had ever seen.

Battle

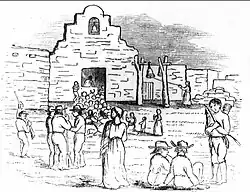

At around 10:00 am on Sunday, May 1, 1782, the Apaches began a surprise attack. The force was split in two and proceeded simultaneously to attack Indian Town and Fort Tucson, clearly intending to capture the fort. Unfortunately for the Spaniards, most of the garrison was not present inside the fortification, and a lot of them were scattered across the town, preparing for Sunday mass. Several Jesuit missionaries were among the population of Tucson, one of whom later reported that around 200 Apaches fought on foot and said he did not attempt to estimate the number mounted on horses. Fighting occurred at three main places: the first was at the bridge connecting Indian Town to Tucson, the second was at the western gate of the presidio, and the third was near the western gate at Lieutenant Miguel de Urrea's home.

At the time, Spanish forces numbered forty-two lancers, twenty dragoons and ten native scouts, including officers. One Apache force first swarmed into the Indian village from the north, where they encountered little resistance before advancing onto the bridge. The other force headed directly for the citadel. A small force of Spanish troops could hold their position at the bridge due to superior weapons, such as muskets, against bows and arrows. Meanwhile, the second Apache unit rushed for the open gate of Fort Tucson, but the advance was halted by cannon and musket fire from Captain Allande and four of his men, positioned on the bridge above the gate. The attack also failed due to Lieutenant Urrea's position, on the roof of his parapet topped house, which flanked the Apache attack. Urrea and his native servant were later credited with delaying a force of over 140 Apaches from joining their main force for the capture of Fort Tucson. The bridge holders, who held against over 200 warriors, were also commended. After two hours of close-quarters combat, the Apaches suffered eight confirmed deaths and dozens more were severely wounded. Apaches were known for removing their dead and wounded from their battlefields immediately after a casualty was sustained. This means that it is likely that more than eight warriors died as a result of the battle, either during or after the engagement.

The Spanish suffered one dead trooper and three wounded; one female civilian was also found to have been killed by the attackers. After seeing the deaths and wounding of so many warriors, the unknown Apache war chief ordered a retreat.

Aftermath

The eight Apache deaths were confirmed by the various reports of the battle, written by the garrison and by the Jesuits there. Other accounts say as many as thirty Apaches were killed during the action. Lieutenant Urrea personally killed or wounded at least five Apaches from the top of his house. His servant killed or wounded a few others. Captain Allande killed two men. One soldier, José Antonio Delgado, who hid in a tree from the beginning to the end of the battle, evading capture, later reported that he witnessed three killed Apaches, being removed from the field by their fellow warriors.

He also reported that several Apache wounded were being carried off into the surrounding desert as well, casualties of cannon fire. The Spanish won the engagement, but the Apaches would return a few months later, on December 15, the Apaches raided some livestock, resulting in another Spanish victory and the deaths of a handful of warriors. Spanish records indicate that only a few Apaches were killed in overall campaigns. The largest Apache body count never numbered more than fifty dead, most likely due to the Apache's evasion tactics.

See also

References

- Bancroft, Hubert Howe, 1888, History of Arizona and New Mexico, 1530–1888. The History Company, San Francisco.

- Cooper, Evelyn S., 1995, Tucson in Focus: The Buehman Studio. Arizona Historical Society, Tucson. (ISBN 0-910037-35-3).

- Dobyns, Henry F., 1976, Spanish Colonial Tucson. University of Arizona Press, Tucson. (ISBN 0-8165-0546-2).

- Drachman, Roy P., 1999, From Cowtown to Desert Metropolis: Ninety Years of Arizona Memories. Whitewing Press, San Francisco. (ISBN 1-888965-02-9.