Billy Caldwell

Billy Caldwell (March 17, 1782 – September 28, 1841) was a Captain in the British Indian Department during the War of 1812, a fur trader, and in his later life a chief of the Potawatomi at Council Bluffs. He was also known as Sauganash, a variant spelling of Zhagnash meaning British or Canadian in the Potawatomi language.[1]

Born in a Mohawk refugee camp near Fort Niagara, Billy was the son of William Caldwell, a Scots-Irish British officer during the American Revolutionary War, and a Mohawk woman, the daughter of a chief named 'Rising Sun'.[2] His name was not short for William. His half-brother, the eldest son of William Caldwell by his French Canadian wife, was named William Caldwell Jr, Billy was only ever called Billy.[3] Due to his Mohawk-speaking mother, English-speaking father, French-speaking step-mother, (Suzanne the daughter of Jacques Baby) his later Potawatomi wives, and years of fur trading, he became multilingual. He did, however, lose the use of the Mohawk language, with which he had been raised in his youth, due to nonuse.[4]

At seventeen Caldwell moved to Chicago to work as a clerk for John Kinzie and Thomas Forsyth. He remained with them for a few years before starting his own independent trade.[5] When the War of 1812 broke out, he arrived alongside the Potawatomi to fight for the British.

After the war Caldwell returned to the Chicago area. Having gained the respect of many bands of Potawatomi, together with Alexander Robinson, he acted as a translator and negotiator on behalf of the prairie bands of the Potawatomi in numerous treaties with the U.S. Federal Government. He was involved in the Second Treaty of Prairie du Chien, the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, and others. For his work, the US granted him life annuities as well as a 1600-acre Half-Breed Tract, known as the Caldwell Reserve, along the North Branch of the Chicago River. These treaties, signed under innumerable pressures, sold their ancestral lands and acquiesced to their removal west of the Mississippi River. In 1835, Caldwell migrated with his people from the Chicago region west to Platte County, Missouri.

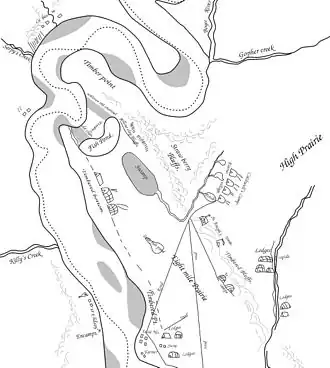

As a result of the Platte Purchase in 1836, Caldwell and his band were removed from Missouri to Iowa Territory, to the area of Trader's Point (Pointe aux Poules) on the east bank of the Missouri River. While living at Trader's Point, Caldwell led a band of approximately 2000 Potawatomi. Their settlement became known as Camp Caldwell. In 1841 Caldwell died; scholars believe it may have been because of cholera.

Early life and education

Soon after the American Revolutionary War, Billy Caldwell, was born in 1782 (as documented through two autobiographical letters)[6] near Fort Niagara to a Mohawk woman. His father was William Caldwell, a Scots-Irish immigrant who came to North America in 1773 and served as a Loyalist soldier in the war.[7] Living first in Virginia, in 1774 his father had fought as an officer with Lord Dunmore and was wounded.[8] After recovering, he went to Fort Niagara in New York, where he fought with Butler's Rangers against Patriot colonists in New York and Pennsylvania.

William Caldwell was likely away on an expedition when Billy was born. He was ordered to Detroit then went south to Kentucky culminating in the Battle of Blue Licks. It's not clear how much of a role William played in his son's early life. He resettled as a Loyalist in Upper Canada, where he was granted land by the British Crown. In addition to clearing land for his own farm, he helped develop the town of Amherstburg, in present-day Ontario.[7]

In 1783, the senior Caldwell married Suzanne Baby (daughter of Jacques Baby), of French-Canadian descent.[8] They had numerous children together, the half-siblings of Billy. When Billy was eleven, his father sent for him to be brought to Detroit. His mother accompanied him but did not stay long.[9] Billy was given a basic Anglo-Canadian education and became Catholic. He was called "naturally smart" and was popular as a result.[10]

Career

At the age of 17, Billy Caldwell entered United States territory for the first time, to learn the fur trade business from Thomas Forsyth and John Kinzie. He kept his British loyalties and learned Potawatomi, an Algonquian language, for dealing with the several tribes of that language family near Lake Michigan.[4] He acted as a trader until the outbreak of the War of 1812.

Caldwell was not at Chicago for the Battle of Fort Dearborn. He had gone south to Vincennes on behalf of Kinzie, who had just killed the translator Jean La Lime, in order to give a statement to Governor Harrison.[11] According to the traditional account, likely a bit fictionalized in Juliette Magill Kinzie's 'Wau-bun, the Early Day in the Northwest', Caldwell arrived just in time to de-escalate the situation and deter young warriors from attacking the Kinzies.[12]

After the Battle of Fort Dearborn, Caldwell returned to Canada to enlist in the British service; he looked for his father's help to gain a commission. The senior Caldwell by then was a Lieutenant Colonel and had gained commissions for his sons by Suzanne. The regular army did not accept Billy Caldwell, but he was commissioned as a captain in the Indian Department.[7] By then he had become influential among the Ojibwa, Odawa, and Potawatomi, tribes inhabiting the area around Lake Michigan, known as the Council of Three Fires.

After the Battle of the River Raisin, Billy was attempting to take a large Kentucky militaman prisoner after he had surrendered. The man thought he was to be killed and jumped on Caldwell and stabbed him in the neck, but Caldwell was saved by a friend before he could be slain. He blamed General Procter for permitting the massacre of unarmed Americans after the battle and called him a coward that was afraid to exercise authority.[13]

In 1814, the Canadians appointed the senior Caldwell as Deputy Superintendent of Indians for the Western District, a position for which the younger Caldwell had competed as well. He was appointed second to his father.[14] In 1815 Amherstburg, Ontario's Commandant, Reginald James, suspended Caldwell Sr. because of problems in supplying the Indians; he appointed Billy Caldwell as Superintendent. The Indian Department quickly found that he could not manage the work and "eased him out" the following year, in 1816.[14]

After healing from his injury at the Raisin, Caldwell fought alongside Tecumseh and the British up until their defeat at the Battle of the Thames. He was disgusted that the British abandoned their indigenous allies when General Proctor made an early retreat before the US forces, leaving Tecumseh and his forces to stand alone.[15] Supposedly Caldwell was beside Tecumseh when he died, but the account has some unrelated inaccuracies and therefore might not be trustworthy.[16] Caldwell stated that he had worked with the British in order to keep his promise to his Anishinaabe friends and establish the long-promised boundary between them and European settlement.[17] The war ended with more land being ceded, however, and Caldwell became disillusioned with the British cause.[15]

The younger Caldwell inherited a plot of land in early 1818 after his father's death, but decided to return to the US. He settled in the Fort Dearborn area (now Chicago).[14] He worked hard to gain the Americans' trust, after years of fighting against them. At the same time he continued to work with a local fur trade firm and became active with the tribes in the area.

In August 1826, Caldwell served as a judge in Peoria County, Illinois's first election. Also in 1826, he was recommended to the Governor of Illinois to hold the Justice of the Peace position for Peoria County. That year, he became an appraiser for the estate of John Crafts, a local trader who died during the year of 1825. In 1827, Caldwell worked for the United States to secure information related to a possible Winnebago uprising.[14]

In 1829, Caldwell became one of several councilors to represent the United Nations of the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi in negotiations with the United States in the Second Treaty of Prairie du Chien. The US was working on Indian Removal, the process that would be authorized by Congress in 1830. At the same time, their agents were also negotiating with the Winnebago for cessions and removal.

I told you all that I would not be a political Indian any more than what would be a benefit to my red brethren— that is to take them over the Mississippi in order to draw them from the scene of destruction [from] the habits of the white's intemperance.

— Billy Caldwell to Francis Caldwell, Esq., March 17, 1834, Chicago.

In 1833, he helped found the first Catholic church in Chicago, Saint Mary of the Assumption. It was located at what is now Lake Street west of State Street.[18]

Caldwell and his band migrated west in 1835, first settling in Missouri west of the Mississippi River. The treaty provided for a $10,000 payment each to Caldwell and Robinson, and a $400 lifetime annuity for Caldwell, with $300 annually for Robinson. Before the US Senate ratified the treaty in 1835, it reduced the lump-sum payments to the men to $5000 each, but left their annuities intact.[18] Robinson and some other Métis remained in Illinois on their private tracts of land, but most of the United Nations Tribes removed to Missouri and then to Iowa.[19]

It has been claimed that Caldwell and Alexander Robinson were appointed as chiefs by the U.S. Federal government in order to vote for land cessions, or even bribed to do so.[20] The notes of the treaties, however, make it clear that the Government did not consider Caldwell and Robinson to be chiefs. It is made clear that they were councilors, freely consulted with, but were not parties to the treaty.[21] It is unclear exactly when Billy Caldwell became a chief. He was not a hereditary chief of the Potawatomi, but commanded great respect and led a band. After his death, in the 1846 proceedings of Treaty No. 247, he was called, "our great chief Mr. Caldwell."[22]

Caldwell Reserve

The U.S. awarded Caldwell a Half-Breed Tract, a 1,600 acre reserve on the North Branch of the Chicago River, as part of the 1829 Treaty of Prairie du Chien. In 1833, in preparation for his removal beyond the Mississippi River, Caldwell began selling off his land via the New York attorney Arthur Bronson. According to his land patent, to be legally binding, each deed had to be personally approved by the president.

The tracts of land herein stipulated to be granted, shall never be leased or conveyed by the grantees, or their heirs, to any persons whatever, without the permission of the President of the United States.

— Second Treaty of Prairie du Chien, 1829

In all, six land sales took place from Caldwell's Reserve. These land transactions included: 80 acres to George W. Dole and Richard Hamilton in June 1833 for $100; 160 acres to Richard Nicolas, Sarah Amantus, Eleanor Hamilton, and infant heirs of Richard Jo and Diana W. Hamilton in July 1833 for $200; 160 acres to Philo Carpenter in July 1833 for $200; 720 acres to Arthur Bronson in 1833 for $900; 160 acres to Captain Seth Johnson in November 1833 for $200; 80 and 160 acres, respectively, to Julius B. Kingsbury in November 1834 for $300. This accounted for 1,440 acres of the original 1,600. The first deed to be approved by the president was the 720 acres to Arthur Bronson, with the others eventually being approved as well. Except, that is, for the northernmost 160 acres of the reserve. Deeds for this land have never been approved by a sitting president, and no original deeds from Caldwell exist to be approved. In theory this land, valued at about 500 million dollars is the property of unknown descendants of Caldwell, if they exist.[23]

Marriage and family

Caldwell's marriage and issue is unclear, and numerous contradictory accounts exist. He is traditionally said to have married three times. The first time to a Potawatomi woman, the daughter or niece of Chief Neescotnemeg, the second time to a daughter of Robert Forsythe, and the third time to a Métis woman in Chicago.[24]

When Father Stephen Badin visited Chicago he baptized three daughters by Caldwell and 'Nannette': Helene, Suzanne, and Elizabeth.[25] Caldwell himself spoke of three daughters and a son, Alexander. He said his favorite daughter, Elizabeth, was on the verge of death in March 1834.[26] In November of the same year he married Saqua LeGrande in Chicago.[27] She had a son from a previous marriage by the name of Pewymo. According to him, Caldwell and Saqua had three daughters in Chicago who all died before adulthood.[28] This creates the possibility that Nannette and Saqua were the same person, and they had been together prior to having their marriage endorsed by Father Badin.

One of Caldwell's wives was the niece or daughter of the powerful Potawatomi chief, Mad Sturgeon,[29] Juliette Magill Kinzie in her book Wau-bun refers to the wife of Caldwell as the daughter of Chief Neescotnemeg, referring to Mad Sturgeon. Alexander Robinson wrote that it was his last wife who was the niece of Mad Sturgeon.[30] Gurdon Saltonstall Hubbard said the same.[31]

It is claimed that his son Alexander died in 1832 from alcoholism,[14] however the timing cannot be correct as in 1834 Caldwell wrote a letter to his half-brother Francis complaining that his son Alexander had recently returned to his home "almost naked" and expressed concern about his "future conduct."[32] The strife could very well have been caused by Alexander's overuse of alcohol.

All of Caldwell's children predeceased him. His stepson Pewymo attempted to sell the remaining portion of Caldwell's reserve in the latter half of the 19th century but the Attorney General halted the proceedings on the recommendation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs.[33]

Caldwell had at least four children, though their mothers are unclear:

- Alexander

- Helene

- Suzanne

- Elizabeth

Indian removal and later years

In 1835, Caldwell and his band of Potawatomi left the State of Illinois and relocated to Platte County, Missouri.

In 1836, as a result of the Platte Purchase, Caldwell and his band were removed from this reservation to Trader's Point on the east bank of the Missouri River in the Iowa Territory. The Potawatomi band of an estimated 2000 individuals settled in a main village called "Caldwell's Camp", located where the later city of Council Bluffs, Iowa developed. (This was on the eastern bank of the river, opposite the present-day city of Omaha, Nebraska.)

From 1838 to 1839, Caldwell and his people were ministered to by the notable Belgian Jesuit missionary Pierre-Jean De Smet, based in St. Louis, Missouri. The Jesuit priest was appalled at the violence and desperation that overtook the Potawatomi in their new home, in large part due to the whiskey trade. After De Smet returned to St. Louis, the Catholic mission was abandoned by 1841.[35][36][37]

Caldwell died on September 28, 1841; it may have been from cholera. His wife Masaqua died in the winter of 1843.

Legacy and honors

- The Sauganash Hotel, completed in Chicago in 1831 was named in honor of Caldwell.

- There is a Sauganash Golf Club in Three Rivers, MI., as well as another on his former reserve, both named in his honor.

- He is the subject of two documentary films: Holy Ground which was limitedly released in theatres in December 2023,[38] and The Negotiator: Billy Caldwell, which sold out its June 20, 2024 screening at the Illinois Holocaust Museum.[39][40][41]

References

- ^ "Potawatomi Language Dictionary - Zhagnash". www.potawatomidictionary.com. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 17, Page 238. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "Billy Caldwell was son of a daughter of a Mohawk chief called the Rising Sun, born at Niagara"

- ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 17, Page 230. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "Col. Caldwell's eldest son by his marriage with [?] Baby, born in 1784, he had named William, after himself, & the Indian son had been known only as Billy Caldwell, so named by his mother."

- ^ a b Draper Mss. Vol. 17, Page 240. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "He conversed freely in English, French + Pottawattamie, but from non-use, had pretty much lost his early knowledge of the Mohawk language."

- ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 17, Page 238. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "When about seventeen he went as a clerk to Forsythe & Kinzie at Chicago in the indian trade, & remained with them three or four years - then went into trade for himself among the Pottawattamies- located at Chicago & that region."

- ^ Billy Caldwell to Francis Caldwell, Esq., March 17, 1834, Chicago. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum. "You recollect this day with make the 52nd time that St. Patrick has gone over my head." [His birthday was St. Patricks day]

- ^ a b c Clifton, James A. Caldwell, Billy. Contained in 'Caldwell Papers' held by the Zhang Legacy Collections Center at Western Michigan University. "Manuscript, apparently in the handwriting of Col. Wm. Caldwell begins as follows: 'l came to America in 1773 and joined Lord Dunmore as an officer. On an expedition against the Indians was wounded June the 9th 1774.' Continues to say he served in Butler's Rangers. He was ordered to Detroit. On 4th of June 1787(?)(sic) he marched against Col. Crawford. In August he fought at Blue Locks (sic) and was with an expedition in 1782. He was paymaster in the late war (evidently 1812). Continues: 'I served until the retreat of the right division of the army under Maj. Gen. Proctor. My sons, 3 of whom were officers of Militia and one Captain of Indian Department.' (the latter was Billy Caldwell)."

- ^ a b "William Caldwell", United Empire Loyalists Association of Canada, accessed 11 August 2011

- ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 17, Page 238. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "When eleven years old was brought to his father . . . His mother, who came with him, did not stay long before she returned."

- ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 17, Page 238. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "Billy went to school some- was naturally smart, & recd. many presents from whites in consequence."

- ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 21, pp. 282-3. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "Le Lime, a Frenchman, was the interpreter of the American garrison at Chicago just before the War of 1812. At an evening party of officers Le Lime drank too freely, & high words ensued between him & John Kinzie Sr. & in self defense, when attacked, he killed Le Lime. It was an unfortunate affair, & Kinzie employed Billy Caldwell to go on a mission to Gov. Harrison at Vincennes with a statement of the case, & Caldwell returned just after the Chicago massacre, & in time to save the Kinzie family. Kinzie had to retire awhile to Milwaukee, afraid of the Indians, for having killed Le Lime."

- ^ Kinzie, Juliette A. Wau-Bun, the Early Day in the North-West. Edited by Eleanor Lytle Kinzie Gordon. Chicago and New York: Rand, McNally & Company, 1901. p 187.

"Billy Caldwell for it was he, entered the parlor with a calm step, and without a trace of agitation in his manner. He deliberately took off his accoutrements and placed them with his rifle behind the door, then saluted the hostile savages.

'How now, my friends! A good-day to you. I was told there were enemies here, but I am glad to find only friends. Why have you blackened your faces? Is it that you are mourning for the friends you have lost in battle?' (purposely misunderstanding this token of evil designs.)

'Or is it that you are fasting? If so, ask our friend, here, and he will give you to eat. He is the Indian's friend, and never yet refused them what they had need of.'

Thus taken by surprise, the

savageswere ashamed to acknowledge their bloody purpose. They, therefore, said modestly that they came to beg of their friends some white cotton in which to wrap their dead before interring them. This was given to them, with some other presents, and they took their departure peaceably from the premises." - ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 21, pp. 283. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "Caldwell said he was at the Raisin fight- that a large heavy man jumped on & stabbed him through the neck- the American had surrendered himself as a prisoner, & Caldwell wished to save him- the man was too powerful for him, had not others interfered & saved him- taking off his antagonist & killed him [sic]. Wau-gosh, or the Fox, who saved Caldwell, lived on Wabash. He blamed Proctor for permitting the massacre of wounded & unresisting prisoners at the Raisin & declared that he was timid & cowardly & afraid to exercise authority."

- ^ a b c d e Gayford, Peter T., "Billy Caldwell: Updated History, Part 2 (Indian Affairs)" Archived August 30, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Chicago History Journal, July 2011, accessed 11 August 2011

- ^ a b Draper Mss. Vol. 21, pp. 283-4. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "He was at the Thames- said Proctor ran off & the English troops gave up too soon, leaving the Indians alone to maintain the unequal fight, which did not last long. He said Proctor was the greatest coward in the land; that he, Caldwell, then left in disgust, regretting that he had taken up arms for the British."

- ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 09, p. 27. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "At that time, Tecumseh and Caldwell were behind a large down tree. . . Tecumseh said: 'we must leave here; they are advancing on us.' The lines at this time were quite close together. Caldwell said he did not wait for a second invitation (for he was very much frightened) but ran. That was the last time that he ever saw Tecumseh alive. Tecumseh was found lying where he had left him. He thought Tecumseh must have been killed within two or three seconds after he left him, or he would have followed."

- ^ Letter from Billy Caldwell to William Claus, undated. Contained in 'Caldwell Papers' held by the Zhang Legacy Collections Center at Western Michigan University. "In reply to your candid letter in which it has given me much satisfaction wherein you mention that I was a serviceable man in his Majesty’s Service at the commencement of the late war, I was 500 miles from home where a very high salary was offered to me to remain in the Indian country to keep the Indians neutral. I was also to be indulged to trade in the Indiana territory, no one was to intrude in any manner whatever — but I had too great a share of true principles — not expecting any reward from Great Britain for my Services, when I did join the army at Amherstberg— it was to support what I had said to the Indians repeatedly long before the war — which it was promised to all natives by the English Governments thorough the late illustrious Brock — in fact, every General that had the command of the army previous to Sir Gordon Drummond, had always behaved in this same manner to the Indians which encouraged them to exert themselves as far as they had it in their power. Prior to the war few Indian Traders in general had succeeded so far as to do away with that impression which the Indians had entertained toward the English nation. — Respecting the revolutionary war when the commander of the forces solicited the Indians to join him, (he promised) that before he would make peace with the Americans that there should be a boundary line drawn between the Indian territory and the Americans."

- ^ a b Gayford, Peter T., "Billy Caldwell: Updated History, Part 3 (The Reserve and Death)" Archived August 14, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Chicago History Journal, (August 2011), accessed 11 August 2011

- ^ R. David Edmunds, "Potowatomis", Encyclopedia of Chicago, accessed 26 July 2012

- ^ Quaife, Milo M., and G. B. Porter. “The Chicago Treaty of 1833.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 1, no. 3 (1918): 290. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4630085. "Roberson [sic] and Caldwell, the principal Chiefs of the Pota- watamie Nation, half whites, and persons whom Robert A. Forsyth can control as he pleases, received $10,000 each, as a bribe to induce them to influence the other Chiefs of the Nation. It is allowed out of the $100,000 appropriated in lieu of reservations. Caldwell was the principal Chief at the massacre of the River Raisin."

- ^ Ratified Treaty No. 189, Documents Relating to the Negotiation of the Treaty of September 26, 1833, with the United Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi Indians (Washington, D.C.: National Archives, National Archives and Records Service, 1833). pp 34-5. “We expressed to you our great satisfaction, when you informed us you had chosen Caldwell & Robinson, whom you had appointed your chief councilors at Prairie du Chien, to treat with us. But we are constrained my children to say to these chiefs that this business must no longer be delayed. These friends whom you have just chosen to advise with, consult and take their opinions about your concerns, but they are not chiefs and we cannot treat with them. The instructions of our Great Father forbid it. There can be but two parties to this treaty. Yourselves, chiefs & headmen constitute one party and the commissioners on the part of your Great Father the other. We do not mean to say we prohibit you from taking council of the men you name or that we have objection to them, but our talk and business must be with the chiefs & headmen only.”

- ^ United States. Ratified Treaty No. 247, Documents Relating to the Negotiation of the Treaty of June 5 and 17, 1846, with the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi Indians. Washington, DC: National Archives, National Archives and Records Service. p 16. "The people who made the Treaty of Chicago are at Council Bluffs. The bones of our great chief Mr. Caldwell are there. Our people at home know, and we know that no other people have a right to sell the lands east of the Missouri."

- ^ Priz, Scott (1 January 2016). "Chicago's Last Unclaimed Indian Territory: A Possible Native American Claim Upon Billy Caldwell's Land, 50 J. Marshall L. Rev. 91 (2016)". UIC Law Review. 50 (1). ISSN 2836-7006.

- ^ “Caldwell, Billy (possibly baptized Thomas, Sagaunash).” Dictionary of Canadian Biography. https://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/caldwell_billy_7E.html. "A Potawatomi woman named La Nanette, of the powerful fish clan, was his first wife; she died shortly after the marriage, whereupon he married a daughter of Robert Forsyth and an Ojibwa woman. After his second wife’s death he again married, this time a person known only as the Frenchwoman, likely the daughter of an influential Métis trader in Chicago."

- ^ Badin, Stephen. Father Badin's Baptismal Register, 1830-1841. University of Notre Dame Archives: Notre Dame University. pp. 10–18.

- ^ Billy Caldwell to Francis Caldwell, Esq., March 17, 1834, Chicago. Courtesy of the Chicago History. "Whilst writing this my favorite daughter Elizabeth six years of age [is] on the point of death- thank God she was baptised by Father Baden."

- ^ Cook County, Illinois, U.S., Marriage and Death Indexes, 1833-1889

- ^ Linn, H.C. Letter to E.A. Hayt, April 7, 1879. In Special Case 125 – Pe‑wo‑mo Deed. Catalog entry no. 596499. National Archives Catalog. National Archives and Records Administration. pp. 395–399. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/596499.

- ^ Gayford, Peter T. "Chief Billy Caldwell, His Chicago River Reserve, and Only Known Surviving Heir (illigetimate Children surviveed in Southern Ontario- Walpole Is. FN, 1827) : A 21st Century Biography on One of North America’s Significant Historical Figures and His Bloodline: Part 1 (Early Life)" Archived September 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, The Chicago History Journal (July 2011), accessed 11 August 2011

- ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 21, pp. 285. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "Can only speak of his last wife- a Pottawottamie woman of St. Joseph- a daughter of Wau-be-ne-wa or White Sturgeon. Nu-scot-nu-meg was her uncle."

- ^ Draper Mss. Vol. 22, pp. 88. Courtesy of the Wisconsin Historical Society. "His wife (his last one- Mr. Hubbard knows nothing of former ones) was a sister of Yellow Head’s- of Yellow Head’s village on the Kankakee"

- ^ Billy Caldwell to Francis Caldwell, Esq., March 17, 1834, Chicago. Courtesy of the Chicago History Museum. "My son Alex came home last Thursday, all most naked. I have not said anything to him yet, about his future conduct- whether he will be a vagrant, or reform for the better."

- ^ Justice, United States Department of (1881). Official Opinions of the Attorneys General of the United States: Advising the President and Heads of Departments, in Relation to Their Official Duties. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Whittaker (2008): "Pierre-Jean De Smet's Remarkable Map of the Missouri River Valley, 1839: What Did He See in Iowa?", Journal of the Iowa Archeological Society 55:1-13.

- ^ Mullen, Frank (1925), "Father De Smet and the Pottawattamie Indian Mission", Iowa Journal of History and Politics 23:192-216.

- ^ Wilson and Fiske (1888) Appletons' Cyclopaedia of American Biography, p. 403.

- ^ Fulton (1882)

- ^ "Documentary shows history of Chicago through Catholic lens".

- ^ "[SOLD OUT] Film & Discussion: "The Negotiator: Billy Caldwell Documentary"". Illinois Holocaust Museum. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ "Column: Do you know the name Billy Caldwell? New documentary is about a Native American intertwined with Chicago's history". Chicago Tribune. 18 June 2024. Retrieved 19 June 2024.

- ^ Movie, The Billy Caldwell. "The Billy Caldwell Movie". The Billy Caldwell Movie. Retrieved 19 June 2024.