Saltrio Formation

| Saltrio Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Early Sinemurian ~ | |

“Salnova” quarry, where most of the fossils come from | |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Calcari Selciferi Lombardi Unit |

| Sub-units |

|

| Underlies | Moltrasio Formation |

| Overlies | Tremona Formation |

| Thickness | 20 m |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Fine to compact arenitic limestones |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 45°54′N 8°54′E / 45.9°N 8.9°E |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 33°06′N 14°48′E / 33.1°N 14.8°E |

| Region | Lombardy |

| Country | Italy, Switzerland |

| Type section | |

| Named for | Saltrio |

| Named by | Taramelli[1] |

Saltrio Formation (Italy)  Saltrio Formation (Lombardy) | |

The Saltrio Formation (Also known as the Broccatello Formation) is a geological formation in Italy and Switzerland.[2] It dates back to the Early Sinemurian, and would have represented a near-epicontinental to shallow environment, judging by the presence of marine fauna such as the nautiloid Cenoceras.[3][4] The Fossils of the Formation were described on the late 1880s and revised on 1960s, finding first marine biota, such as Crinoids, Bivalves and other fauna related to Epicontinental basin deposits.[5][6]

Salnova Quarry

The main outcrop of the formation, represents an active private extraction site. The first extraction activities of the famous Saltrio stone give back to the times of the ancient Romans, with modern reports of activity in this quarry since 1400.[7] In the Monte Oro area, on the southern slope of Monte Orsa, there were numerous trench quarries which were used to extract this precious rock, used both for structural constructions and for the production of artefacts and artistic works. In more recent times the mining activity has been transformed and we have moved from the extraction of stone for construction to the extraction for the production of stabilized and split crushed stone, useful for the production of motorway foundations and mixtures for the production of asphalt. To date it is the only active quarry where Saltrio stone is extracted.[7]

In today's quarry what is mainly known as the Saltrio Formation emerges, i.e., a group of stratified rocks dating back to the Lower Jurassic. The stratigraphy, however, is much more complex, even if so far no study has focused on this topic. Inside the quarry, Dolomia principale sediment emerges dating back to the Upper Triassic (Norian); yet the succession is dominated by the Saltrio Formation, here 15-20 meters thick.[8]

Above, the Moltrasio Formation emerges, a greyish-brown limestone composed of biocalcarenite and containing widespread nodules of spongolitic silica. This rock is rarely fossiliferous except in the contact areas between the Formations. At the roof of the Moltrasio Fm, a whitish yellow limestone emerges, again of marine-pelagic origin, where there is a lot of micro-diffused silica within the sediment.[8]

Since the early 1900s, fossil finds have been known in the Salnova Quarry and in the various quarry sites present in the surroundings of this site. The first written testimonies, and subsequent revisions, are reported starting from the sixties by Giulia Sacchi Vialli. The scholar describes the fossil faunas of Saltrio by listing and detailing various taxa belonging to ammonoids, nautiloids, gastropods, crinoids, brachiopods and bivalves.[6]

In that period, the great phase of extraction of ornamental stone using manual-mechanical methods had just ended in the quarry. Paleontologists could only recover fossils from the waste flakes near the quarry and therefore the possibility of seeing more specimens was limited to the length of manual operations. In those years, however, the quarry was acquired by Salnova SPA (1969): the purpose of the extracted material, and therefore the extraction method and processing, changed. From classic and manual extraction we move on to the use of heavy mechanical means and extraction with explosives: the moved rubble increases considerably, making it easier to observe other specimens, new lithologies and above all different faunas.[7]

The fauna present at the base of the Saltrio Formation is condensed and includes ammonoids of species attributed to the entire Upper Sinemurian. The taxa attributable to the Lower Sinemurian found in the Saltrio quarries probably come from the base of the formation or have been reworked.[6] According to Sacchi-Vialli, the Formation includes taxa indicative of all the biozones between the Bucklandi Zone (Lower Sinemurian) and the Obtusum Zone, and possibly also of the Oxynotum Zone of the Upper Sinemurian, present at the base of the Formation.[6] The contact between the Main Dolomite and the Saltrio Formation also contains selachian teeth, glauconite and phosphated internal models of ammonites.[9]

Description

The Saltrio layers represent a unique sedimentary environment that is different from both the "Formazione di Saltrio" and the "Saltrio calcarenite" described by earlier researchers. These layers are characterized by being transgressive deposits, meaning they formed as the sea advanced over previously exposed land. The Saltrio deposits show signs of stratigraphic condensation, which refers to slow sediment accumulation over time, often resulting in hardgrounds, surfaces drilled by marine organisms, and the presence of minerals like Glauconite and Phosphorite.[10] Biologically, these layers are rich in fossils, especially Encrinite (crinoid-rich limestones) and bivalve lumachellas (fossilized bivalve shells). Other marine creatures like cephalopods and brachiopods appear occasionally. Faunas from the condensed Saltrio beds indicate early subsidence in the Hettangian. Additionally, the involutine limestones with a rich ammonite fauna support subsidence during the same period. The sediment composition varies in different areas, often containing reworked material from older rocks.[10] The Saltrio environment was complex, with different layers showing distinct conditions. In some areas, the Saltrio layers blend with the "Broccatello d'Arzo", a related limestone formation, but they can still be separated based on differences in their structure and fossil content. The region also experienced sedimentary discontinuities, where layers were not deposited continuously, likely due to tectonic activity or submarine erosion.[10]

The stratigraphic sequence at the Galli quarry, located at an elevation of approximately 700 meters on the southeastern flank of the ridge above Saltrio, represents one of the most detailed exposures of the Saltrio Formation.[11] This section, reaching a total thickness of about 17 meters, begins atop underlying dolomite and consists of a series of carbonate-dominated layers that reflect varying depositional conditions in a marine setting.[11]

At the base, a thin dolomitic breccia layer (up to 1 meter thick) contains angular dolomite fragments embedded in a lighter calcareous-dolomitic matrix. This is overlain by a 0.3-meter-thick marly limestone with minor detrital components, displaying an olive-gray to greenish hue and iron oxide stains. Next is a 0.8-meter saccharoidal limestone with sparse marl, glauconite, and quartz grains, followed by a thin (0.1–0.2 meter) reddish-brown clay horizon.[11]

Above this, a 1-meter oolitic limestone features intact and broken ooids in a compact calcareous cement, grading from white to grayish-yellow. This transitions into a 3-meter unit of finely to coarsely detrital marly limestone rich in organic fragments, shifting from gray-pink at the base to yellowish upward, with iron oxide patches. A 0.8-meter calcareous breccia with diverse clasts and ooids follows, exhibiting irregular surfaces.[11]

The upper part includes a 5.5-meter marly limestone with minimal detritus, progressing from gray-ashy at the base to dark smoky due to bituminous content. The sequence concludes with a 5-meter dark limestone containing chert nodules, which become more abundant and marly toward the top, before passing into overlying cherty limestones approximately 200 meters thick.[11]

Paleoenvironment

From the Hettangian to earliest Sinemurian, the western Lombardy Basin featured a notable continental area, wider than previously estimated, characterized by a warm, humid paleoclimate. This region transitioned gradually from Upper Rhaetian shallow-water carbonates to Lombardian siliceous limestones and thick Lowermost Jurassic. Dinosaur fossils from the Saltrio Formation may have been transported from this continental zone or the Arbostora swell in Switzerland, an emerged structural high that divided the subsiding Monte Nudo (east) and Monte Generoso (west) basins. The swell overlay a carbonate platform connected to broader shallow-water areas extending west to southeast, forming a large northern gulf influenced by horst and graben tectonics. Outcrops of "terra rossa" paleosols, including those at Castello Cabiaglio-Orino, west of Saltrio, indicate emerged lands during the Hettangian-Sinemurian, with forests covering the modern Lake Maggiore area, evidenced by large plant fragments in the coeval/younger Moltrasio Formation.[12][13] Recovered flora from Cellina and Arolo on Lake Maggiore's eastern side includes Bennettitales (Ptilophyllum) and Conifers (Pagiophyllum, Brachyphyllum), suggesting inland dry-warm conditions.[14]

In the early Sinemurian, the Arbostora swell submerged into a shallow open sea (ramp-slope), still bordered south and southwest by emerged land. Dinosaur bones were likely washed into the Monte Nudo gulf during this phase, supported by terrigenous sands from eroded igneous/metamorphic rocks and terrestrial plants in the limestones. While plants (mainly Araucariaceae and Bennettitales leaves/branches) and sands could have been transported by wind or currents, the nearest major continental land was the Sardinia-Corsica mountains, tens of kilometers WNW.[15] Coeval dinosaur footprints in Trento province (160 km east of Saltrio) challenge the traditional atoll model, indicating larger emerged lands for sustaining herbivorous prey and fresh water.[16][17] The Peri-Adriatic platforms likely featured temporary continental bridges connecting Laurasia and Gondwana across central Tethys, enabling migration and potential isolation leading to endemism and dwarfism in terrestrial faunas.[18]

The Saltrio Formation records a shallow marine depositional environment on a subsiding carbonate platform along the Tethyan passive margin. The 17-meter-thick sequence at the Galli quarry transitions from basal dolomitic breccia (transgressive reworking) through marly and oolitic limestones (higher-energy subtidal shoals) to bituminous, cherty limestones (deeper open-shelf with reduced oxygenation). Faunal assemblages, dominated by cephalopods (ammonites like Asteroceras, nautiloids Cenoceras), bivalves (Cardinia), gastropods (Pleurotomaria), and brachiopods (Lobothyris punctata), indicate normal-marine, oxygenated waters with deepening trends.[11] Fragmentary ichthyosaur remains and bioeroded dinosaur bones (e.g., Saltriovenator zanellai) suggest transport from nearby terrestrial sources into coastal lagoons.[4] Regional studies link this to platform drowning amid rifting, with carbon-isotope excursions implying volcanic influences and ocean perturbations. A modern analogue is the Bahama Banks, featuring oolitic shoals and lagoons in a subtropical passive-margin setting.[11]

Invertebrate fauna

Porifera

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Endostoma[19] |

|

Spicules & Imprints |

|

A Calcareous sponge of the family Endostomatidae. |

|

| Stellispongia[19] |

|

Spicules & Imprints |

|

A Calcareous sponge of the family Stellispongiidae. | |

| Neuropora[20] |

|

Spicules & Imprints |

|

A Demosponge of the family Neuroporidae. |

Brachiopoda

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arzonellina[21] |

|

Shells |

|

A Terebratulidan of the family Arzonellinidae. | |

| Aulacothyris[19] |

|

Shells |

|

A Terebratulidan of the family Zeilleriidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Wellerellidae. Identified originally as "Rhynchonella variabilis". |

||

| Furcirhynchia[19] |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Rhynchonellidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Spiriferinidae. Was identified originally as "Spiriferina haasi". |

||

|

Shells |

|

A Terebratulidan of the family Lobothyrididae. Was identified originally as "Terebratula punctata". |

||

| Prionorhynchia[19][21][23] |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Prionorhynchiidae. | |

| Rimirhynchia[19] |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Rhynchonellidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Wellerellidae. |

| |

| Rhynchonellina[19] |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Dimerellidae. | |

| Tetrarhynchia[19] |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Tetrarhynchiidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Spiriferinidae. |

||

| Sulcirostra[21] |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Dimerellidae. | |

| Viallithyris[22] |

|

Shells |

|

A Rhynchonellidan of the family Rhynchonellidae. | |

| Zeilleria[6][19] |

|

Shells |

|

A Terebratulidan of the family Zeilleriidae. |

Bryozoa

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ceriopora[6] |

|

Imprints |

|

A Cyclostomatidan of the family Cerioporidae. |

Bivalves

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Astartidae. Some shells identified as Cardium probably belong to this genus. |

||

|

Shells |

|

|||

|

Shells |

|

A Scallop of the family Pectinoidae. It was identified originally as "Pecten (Pseudamusium) hehlii". |

||

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Cardiniidae. |

||

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Cardiniidae. |

||

| Entolium[5] |

|

Shells |

|

A Scallop of the family Pectinoidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

A Scallop of the family Pectinoidae It was identified as "Pecten (Chlamys) textorius". |

||

|

Shells |

|

|||

| Gresslya[5] |

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Pleuromyidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

|||

|

Shells |

|

An Oyster of the family Gryphaeidae. |

| |

|

Shells |

|

|||

|

Shells |

|

|||

| Mactromya[5] |

|

Shells |

|

An Adapedont of the family Edmondiidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

A Mussel of the family Mytilidae. Identified as the genus "Modiola", now junior synonym of Modiolus. |

||

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Pleuromyidae. |

||

|

Shells |

|

|||

| Parallelodon[5] |

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Parallelodontidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

A Scallop of the family Pectinoidae. |

| |

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Pholadomyidae. |

||

|

Shells |

|

A File Clam of the family Limidae. Identified originally as "Lima (Plagiostoma) gigantea". |

| |

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Pleuromyidae. |

||

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Lucinidae. Identified originally as "Fimbria (Sphaeriola) sp.". |

||

|

Shells |

|

A Clam of the family Prospondylidea. |

Gastropods

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticonulus[25] |

|

Shells |

|

A Snail of the family Trochidae. | |

| Bathrotomaria[6] |

|

Shells |

|

A Snail of the family Pleurotomariidae. | |

| Coelostylina[25] |

|

Shells |

|

A Snail of the family Coelostylinidae. | |

| Discotoma[6] |

|

Shells |

|

A Snail of the family Pleurotomariidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

A Snail of the family Pleurotomariidae. |

| |

| Ptychomphalus[6] |

|

Shells |

|

A Snail of the family Eotomariidae. | |

| Pyrgotrochus[6] |

|

Shells |

|

A Snail of the family Pleurotomariidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

|||

| Trochotoma[6] |

|

Shells |

|

A Snail of the family Pleurotomariidae. |

Cephalopoda

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Arietitidae. |

||

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Arietitidae. |

%252C_Lee_Kong_Chian_Natural_History_Museum_(103314).jpg) | |

| Arnioceras[2] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Arietitidae. | |

| Asteroceras[2] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Arietitidae. |  |

| Aulacoceras[6] |

|

Phagmocones |

|

A Belemnite of the family Aulacoceratidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

A Nautilidan of the family Cenoceratidae. Cenoceras was identified as member of the genus Nautilus originally. |

| |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Arietitidae. |

||

| Crucilobiceras[11] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Eoderoceratidae. | |

| Euasteroceras[2] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Arietitidae | |

| Lytoceras[11] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Lytoceratidae | |

| Microderoceras[2] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Eoderoceratidae. |  |

| Nannobelus[6] |

|

Phagmocones |

|

A Belemnite of the family Belemnitidae. | |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Oxynoticeratidae. |

| |

| Paracoroniceras[2] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Arietitidae. | |

| Paradasyceras[2] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Juraphyllitidae. | |

| Schlotheimia[11] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Schlotheimiidae | |

| Vermiceras[2] |

|

Shells |

|

An Ammonitidan of the family Arietitidae. |

Echinoderms

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Isocrinus[29] |

|

Multiple ossicles |

|

A Sea lily of the family Isocrininae. |

|

|

Miocidaris[24] |

|

Multiple ossicles |

|

An Echinoidean of the family Miocidaridae. |

|

|

Millericrinus[24] |

|

Multiple ossicles |

|

A Sea lily of the family Millericrinida. |

|

|

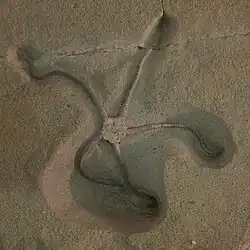

MSNVI 044/017, dorsally-ventrally oriented ophiuroid |

|

An Ophiuridan of the family Ophiodermatidae. Extant tropical species like Ophioderma are benthic predators and scavengers that show the same short spines seen in Palaeocoma.[30] |

| |

|

|

|

A Sea lily of the family Pentacrinitidae. |

| |

| Plegiocidaris[6] |

|

Multiple ossicles |

|

An Echinoidean of the family Cidaridae. |  |

Vertebrate fauna

In 2016 new vertebrate remains were discovered in the Salnova quarry, the remains are being studied to understand if it is a new dinosaur or some other creature.[31][32] Latter has been confirmed to be Marine Diapsid material.[33]

Fish

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Notidanoides[9] |

|

|

|

A Crassodontidanidae Hexanchiform | |

|

Indeterminate |

|

|

Non-determined afinitties |

||

| Sphenodus[9] |

|

|

|

An Orthacodontidae Synechodontiform |

Icthyosaurs

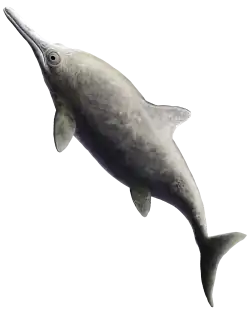

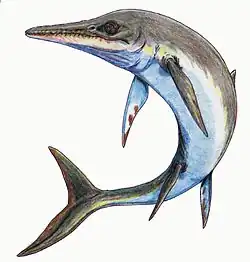

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

A Neoichthyosaurian of the family Ichthyosauridae. |

| |

|

|

|

A Neoichthyosaurian of the family Temnodontosauridae. Quoted on the 1880s, specimen that apparently has never been described or figured and whose present repository is unknown |

|

Pterosaurs

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

"Pterodactylus" longirostris |

|

|

A Pterosaur. Quoted on the 1880s, specimen that apparently has never been fully described or figured and whose present repository is unknown |

|

Dinosaurs

| Genus | Species | Material | Location | Notes | Images |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

The oldest known Ceratosaur, falling outside Neoceratosauria, being sister taxa to the maroccan genus Berberosaurus. Saltriovenator is also the largest known Theropod of the Lower Jurassic. It probably was washed into the Sea.[4] Traces on the bones show that the dinosaur carcass remained exposed to the water-sediment interface for months or years, long enough to first be defleshed by mobile scavengers, then colonized by a microbial community that spanned the bone–water interface, which in turn attracted slow-moving grazers and epibionts.[4] |

|

See also

- List of fossiliferous stratigraphic units in Italy

- List of dinosaur-bearing rock formations

- Moltrasio Formation, Sinemurian fossiliferous formation of Italy

- Coimbra Formation, Sinemurian fossiliferous formation of Portugal

- Aganane Formation, Pliensbachian Formation of Morocco

References

- ^ a b c Stoppani, A. (1857). Studi geologici e paleontologici sulla Lombardia. Milano: Tipografia Turati. p. 461. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sacchi-Vialli, Giulia; Cantaluppi, Gianmario. "Revisione Della Fauna Di Saltrio Vol. I E II Premessa Le Ammoniti [Revision of the Saltrio fauna, vol. I and II - Introduction - Ammonites]". Atti Dell' Istituto Geologico Della Università Di Pavia. 13 (1): 1–33.

- ^ a b c Weishampel, David B; et al. (2004). "Dinosaur distribution (Early Jurassic, Europe)." In: Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. Pp. 532–534. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dal Sasso, Cristiano; Maganuco, Simone; Cau, Andrea (2018-12-19). "The oldest ceratosaurian (Dinosauria: Theropoda), from the Lower Jurassic of Italy, sheds light on the evolution of the three-fingered hand of birds". PeerJ. 6 e5976. doi:10.7717/peerj.5976. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6304160. PMID 30588396.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Sacchi Vialli, G. (1963). "Revisione Della Fauna Di Saltrio Vol. IV I Lamellibranchi [Revision of the Saltrio Fauna Vol. IV The Lamellibranchs]". Atti dell’Istituto geologico dellaUniversità di Pavia. 14 (1): 1–10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Vialli, G. S. (1964). "Revisione Della Fauna Di Saltrio Vol. V Gast. Cefal. Brioz. Brach. Echino. Vertebrati [Revision of the Saltrio Fauna, Vol. V, Gast. Cephalopods, Bryozids, Brach, Echinoderms. Vertebrates]". Atti 1st Geol Favia. 15 (4): 3–23. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Media, My (2015-01-22). "Materiali inerti, massi da scogliera, pietre d'opera, pietre per muratura". Salnova (in Italian). Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ a b Cita, Maria Bianca (1965-01-01). Jurassic, cretaceous and tertiary microfacies from the Southern Alps (Northern Italy). BRILL. doi:10.1163/9789004611252. ISBN 978-90-04-61125-2.

- ^ a b c Beaumont, Gérard de (1960). Contribution à l'étude des genres Orthacodus Woodw. et Notidanus Cuv. (Selachii) (in French). Birkhäuser.

- ^ a b c Kalin, O.; Trumpy, D.M. (1977). "Sedimentation und Paläotektonik in den westlichen Südalpen: Zur triasisch-jurassischen Geschichte des Monte Nudo-Beckens". Eclogae Geol Helv. (2): 295–350. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Sacchi Vialli, Giulia (1964). "Revisione Della Fauna Di Saltrio Vol. VI Considerazioni Conclusive [Revision of the Saltrio fauna, vol. VI - Concluding remarks]". Atti dell’Istituto geologico dellaUniversità di Pavia. 15 (5): 1–13.

- ^ Leuzinger, P. (1925). "Geologische Beschreibung des Monte Campo dei Fiori u. der Sedimentzone Luganersee-Valcuvia. Mit 3 Tafeln und 6 Textfiguren. Inaugural-dissertation". Buchdruckerei Emil Birkhäuser & Cie., Basel. 1 (1): 1–177.

- ^ Wiedenmayer, F. (1963). "Obere Trias bis mittlerer Lias zwischen Saltrio und Tremona:(Lombardische Alpen)". Eclogae Geologicae Helv. 56 (11): 22–148. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Lualdi, A. (1999). New data on the Western part of the M. Nudo Basin (Lower Jurassic, West Lombardy) Tubingen Geowissenschaftliche Arbeiten, Series A, 52, 173-176.

- ^ a b Dalla Vecchia, F.M. (2001). "A new theropod dinosaur from the Lower Jurassic of Italy, Saltriosaurus". Dino Press. 3 (2): 81–87.

- ^ Avanzini, M.; Petti, F. M. (2008). "Updating the dinosaur tracksites from the Lower Jurassic Calcari Grigi Group (Southern Alps, Northern Italy)". Proceedings of the Ichnology Session of Geoitalia 2007. Studi Trent. Sci. Nat., Acta Geol. 83 (4): 289–301. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Masetti, D.; Claps, M.; Giacometti, A.; Lodi, P.; Pignatti, P. (1998). "I Calcari Grigi della piattaforma di Trento (Lias inferiore e medio, Prealpi Venete)". Atti Ticinensi di Scienze della Terra. 40 (5): 139–183. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ Dal Sasso, Cristiano (2003). "Dinosaurs of Italy". Comptes Rendus Palevol. 2 (1): 45–66. Bibcode:2003CRPal...2...45D. doi:10.1016/s1631-0683(03)00007-1. ISSN 1631-0683. Retrieved 16 August 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Wiedenmayer, Felix (1963). "Obere Trias bis mittlerer Lias zwischen Saltrio und Tremona (Lombardische Alpen): die Wechselbeziehung zwischen Stratigraphie, Sedimentologie und syngenetischer Tektonik". Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae. 56 (2): 529. doi:10.5169/seals-163041. ISSN 0012-9402.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Parona, C. F. (1897). "I Nautili del Lias inferiore di Saltrio in Lombardia". Bullettino della Società Malacologica Italiana. 20: 7–20. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ a b c Sulser, Heinz (2004). "Arzonella exotica n. g. n. sp., a new brachiopod of indeterminate systematic position from the Lower Liassic (Broccatello) of Arzo (Southern Alps of Switzerland): A short note". Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae. 97 (3): 423–428. doi:10.1007/s00015-004-1136-3. ISSN 0012-9402.

- ^ a b c d e f Parona, C.F. (1884). "I brachiopodi liassici di Saltrio ed Arzo nelle Prealpi Lombarde". Memorie del Reale Istituto Lombardo di Scienze e Lettere. 15 (1): 227–262.

- ^ Shi, Xiao-ying; Grant, Richard E. (1993). "Jurassic Rhynchonellids: Internal Structures and Taxonomic Revisions". Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology (73): 1–190. doi:10.5479/si.00810266.73.1. ISSN 0081-0266.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Parona, C. F. (1890). "I fossili del Lias inferiore di Saltrio in Lombardia". Atti della Società Italiana di Scienze Naturali. 33: 69–104. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ a b c d Parona, C.F. (1895). "I fossili del Lias di Saltrio in Lombardia; Parte 2: Gasteropodi". Bollettino Società Malacologica Italiana. 18: 161–184.

- ^ Monari, Stefano; Valentini, Mara; Conti, Maria Alessandra (2011). "Earliest Jurassic Patellogastropod, Vetigastropod, and Neritimorph Gastropods from Luxembourg with Considerations on the Triassic—Jurassic Faunal Turnover". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (2). doi:10.4202/app.2010.0098.full#bibr93 (inactive 5 August 2025). ISSN 0567-7920. Archived from the original on 2024-12-28. Retrieved 2025-07-27.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of August 2025 (link) - ^ a b c d Parona, C.F. (1896). "Contribuzioni alla conoscenza delle ammoniti liasiche di Lombardia, Parte 1: Ammoniti del Lias inferiore di Saltrio" (PDF). Mémoires de la Société Paléontologique Suisse. 23: 1–45. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ Sacchi Vialli, Giulia (1962). "Revisione Della Fauna Di Saltrio Vol. III I Nautili [Revision of the Fauna of Saltrio Vol. III The Nautiloids]". Atti dell’Istituto geologico dellaUniversità di Pavia. 13 (1): 1–14.

- ^ Jaselli, L. (2021). "Reappraisal of the Lower Jurassic crinoid fauna of Lombardy (Italy): insights on regional museum collections". Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 60 (2): 112. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ a b Jaselli, L. (2015). "The Lower Jurassic (Early Sinemurian) ophiuroid Palaeocoma milleri in the palaeontological collection of the Museo di Storia Naturale "Antonio Stoppani"(Italy)". Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 54 (3): 188. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

- ^ Giorno, Il (2016-03-10). "Saltrio, trovati resti ossei: potrebbero appartenere a un dinosauro". Il Giorno (in Italian). Retrieved 2021-12-30.

- ^ "La Soprintendenza conferma, sono ossa del Giurassico". VareseNews (in Italian). 2016-03-11. Retrieved 2021-12-30.

- ^ a b c d Zazzera, Andrea; Brivio, Keefer; Rolfi, Jacopo; Bindellini, Gabriele; Balni, Marco; Renesto, Silvio (2022). "New marine diapsid remains from the Saltrio Formation (Sinemurian) Monte San Giorgio, UNESCO WHL". Paleodays 2022. 22 (1): 133. Retrieved 26 May 2023.

Further reading

- F. M. Dalla Vecchia. 2001. Terrestrial ecosystems on the Mesozoic peri-Adriatic carbonate platforms: the vertebrate evidence. VII International Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems. Asociación Paleontología Argentina, Publicación Especial 7:77-83

.jpg)

_1_(15206675956).jpg)