SS E.M. Clark

SS E.M. Clark on April 2, 1928 | |

| History | |

| Name | Victolite (1921–1926) E.M. Clark (1926–1942) |

|---|---|

| Namesake | Edgar M. Clark, vice president of Standard Jersey |

| Owner | Imperial Oil (1921–1926) Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (1926–1942) |

| Operator | Imperial Oil (1921–1926) Standard Shipping Company (1927–1935) Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (1935–1942) |

| Registry | Halifax, Nova Scotia (1921–1926) Wilmington, Delaware (1926–1942) |

| Ordered | July 1, 1919 |

| Builder | Federal Shipbuilding Company |

| Yard number | 49 |

| Laid down | July 22, 1920 |

| Launched | June 24, 1921 |

| Sponsor | Mrs. C. O. Stillman |

| Completed | July 8, 1921 |

| In service | 1921–1942 |

| Renamed | 1926 (to E.M. Clark) |

| Identification | Call sign: KGAB IMO number: 1150466 Official number: 1150466 (1921–1926) 225482 (1926–1942) |

| Fate | Sunk by U-124 on March 22, 1942 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage | 9,647 GRT 16,030 DWT |

| Length | 499.2 feet (152.2 m) |

| Beam | 68.1 feet (20.8 m) |

| Depth | 30.5 feet (9.3 m) |

| Propulsion | Dual-screw |

| Speed | 11 knots (13 mph; 20 km/h) |

| Capacity | 119,414 barrels (5,015,388 gallons) |

SS E.M. Clark was a Canadian- and American-registered oil tanker built in 1921 for Imperial Oil as Victolite. She was transferred to the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey in 1926 and renamed E.M. Clark. She was torpedoed and sunk by U-124 on March 18, 1942, 22 miles (35 km) off the Diamond Shoals of North Carolina.

Construction

Victolite was ordered on July 1, 1919.[1] The tanker was built in Kearny, New Jersey, by the Federal Shipbuilding Company.[2] Her keel was laid on July 22, 1920, as yard number 49. She was launched on June 24, 1921, sponsored by Mrs. C.O. Stillman, the wife of the president of Imperial Oil.[3] When Victolite was completed the next month, she was assigned the official and IMO number 1150466,[4] as well as the call sign KGAB.[5] She was delivered on July 8, 1921, flying the Canadian flag, and was registered in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[3]

Specifications

The tanker was 499.2 feet (152.2 m) long between perpendiculars, 68.1 feet (20.8 m) wide, and had a depth of 30.5 feet (9.3 m).[6] She had a gross register tonnage of 9,647, and a deadweight tonnage of 16,030.[1] Victolite was powered by two vertical reciprocating triple expansion steam engines,[6] powering her two triple-screw propellers and giving her a maximum speed of 11 knots (13 mph; 20 km/h).[4] She had a cargo capacity of 119,414 barrels (5,015,388 gallons).[6]

Service history

Victolite carried oil from ports in the countries of Mexico, Peru, and Nicaragua, as well as the US states of Texas, California, and Louisiana, to Imperial Oil's refineries in Halifax. Imperial Oil removed the foreign countries from the tanker's service in 1925, instead having her operate between San Pedro, Los Angeles to Halifax.[3]

Victolite was sold in 1926 to the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey and renamed E.M. Clark after Edgar M. Clark, then-vice president of the company.[6] The tanker's official number was also changed to 225482.[4] She was re-registered in New York and began flying an American flag.[3]

E.M. Clark was given to a subsidiary of Jersey Standard, the Standard Shipping Company, in 1927. She was transferred back to her parent in 1935.[4] Her port of registry was also changed to Wilmington, Delaware. She became very active in North America.[3]

World War II

During World War II, E.M. Clark made a total of 41 voyages and carried almost five million barrels of oil to New York for the Allied war effort.[6][7] The tanker made six voyages in 1939 following the outbreak of war in September. In 1940, she made 13 voyages despite being docked in from August 14 to October 22. She was on a route from the Gulf states to the Atlantic states for all of 1941 except for one voyage that took her to Brazil, totaling 20 voyages that year. E.M. Clark only made two voyages in 1942, to Baltimore and Los Angeles, before embarking on her final voyage.[3]

Sinking

E.M. Clark left Baton Rouge, Louisiana, on March 11, 1942.[3] She carried 118,000 barrels of heating oil and was bound for New York. She was under the command of Captain Hubert Hassel.[2] The Commandant of the Eighth Naval District gave the tanker's captain and crew confidential and detailed instructions to follow on the voyage, which included information about how the ship was to travel and radio communication protocols.[3]

The weather turned poor while sailing up the East Coast on March 17, becoming "squally with lightning and rainfalls and wind [from the] south-west." Captain Hassell retired to his stateroom at 12:35 AM on March 18.[8]

Attack

On March 18, 1942, U-124 spotted E.M. Clark 22 miles (35 km) southwest of the Diamond Shoals Light Buoy. She was traveling fully blacked-out, in moderately rough seas, at a speed of 10.5 knots (12.1 mph; 19.4 km/h). The tanker was actively silhouetted by light caused by nearby thunderstorms.[2] The U-boat had already sunk the Honduran vessel Ceiba, American tanker Acme, and Greek vessel Kassandra Louloudis.[3]

The German submarine snuck closer to the tanker using the squall-like conditions as cover.[7] It fired one torpedo at 1:27 AM, which struck E.M. Clark amidships on the port side, 8–10 feet (2.4–3.0 m) below the waterline.[2] The explosion brought down her radio antenna and forward mast, blown in the #3 tank, forced the tanker's deck up,[3] and destroyed Lifeboat 2. Captain Hassell ordered the engines to be set to "full astern" and then "stop". He then went to the radio operator and ordered him to "get on the air."[8]

The radio operator realized the antenna was broken after trying to send SOS and SSSS, and went outside in an attempt to fix the antenna and rig an emergency radio.[7][8] During this time, U-124 fired a second torpedo, which struck the bow between the #1 cargo tanks and the forward dry cargo hold at 1:29 AM.[3] The ship's whistle was damaged, causing it to emit a continuous and steady roar.[8]

Captain Hassell gave the order to abandon ship, seeing as E.M. Clark was fatally wounded. Thirteen men got into Lifeboat 1 and twenty-six got into lifeboat 4. Lifeboat 1 returned to the ship after spotting a wiper standing on the tanker's railing. He leapt into the water and was promptly rescued by the lifeboat. Only one crewman, a utilityman sleeping in the hospital room, was missing. Before escaping in Lifeboat 1, Captain Hassell gathered all the tanker's confidential papers and codes, placed them in a weighted bag, and threw the bag overboard.[3]

E.M. Clark sank within 10 minutes of the first torpedo hitting her. She plunged bow-first into water that was covered in oil, making her crew sick from the fumes. The whistle finally stopped blowing for around ten seconds before the funnel went underwater, only to resume its noise until the tanker finally sank.[8] U-124 remained on the scene for about an hour and a half, its light "swinging back and forth over the place where the ship had sunk." It departed around 3:00 AM and headed northeast, disappearing from the survivors' view.[3]

Rescue and aftermath

At 7:00 AM, the survivors in Lifeboat 1 were rescued by the American destroyer USS Dickerson.[3] They were transferred to the motor surfboat USCGC CG-5426 and taken to the United States Coast Guard station at Ocracoke.[2] They were delivered to Atlantic, North Carolina.[8] They were subsequently taken to Morehead City and eventually New York, arriving at their intended destination on March 20. The survivors in Lifeboat 4 were picked up by the Venezuelan tanker Catatumbo and taken to Cape Henry, though they were eventually transferred to Norfolk, Virginia. The Standard Oil Company of New Jersey received an insurance payout of $1,202,250 for the hull of E.M. Clark.[3]

Wreck

E.M. Clark (shipwreck and remains) | |

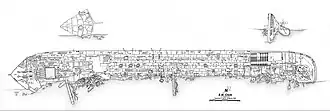

The site plan for the wreck of E.M. Clark | |

| Location | Address Restricted, near Buxton, North Carolina |

|---|---|

| MPS | World War II Shipwrecks along the East Coast and Gulf of Mexico |

| NRHP reference No. | 13000780[9] |

| Added to NRHP | September 25, 2013 |

E.M. Clark is 240 feet (73 m) below the surface of the water, 23 miles (37 km) off of Cape Hatteras.[3] She is completely intact from bow to stern, though she lies on her port side. The exterior plates on her hull only have minor amounts of deterioration, caused by the strong currents at the site. Her starboard anchor is in place, though the port anchor is buried in the sediment. The rudder and two propellers are intact with the entire starboard propeller shaft visible, though only half of the port one is. The highest point of the shipwreck is the starboard edge of the main deck, which sits about 50 feet (15 m) above the seafloor.[7]

The shipwreck is now an artificial reef for the ecosystem, home to a wide variety of marine life.[3] Such creatures that are commonly found at the wrecksite include sand tiger sharks, greater amberjacks, great barracudas, northern sea robins, and loggerhead sea turtles.[6]

The wrecksite of E.M. Clark was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 25, 2013.[10]

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Dare County, North Carolina

- List of shipwrecks of North Carolina

References

- ^ a b "TT E M Clark". shipvault.com. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e Helgason, Guðmundur. "E.M. Clark". uboat.net. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Marx, Deborah; James, Delgado (July 15, 2013). National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (PDF). Office of National Marine Sanctuaries.

- ^ a b c d Visser, Auke. "E. M. Clark - (1921-1942)". Auke Visser's International Esso Tankers site. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

- ^ Tony, Allen. "SS E. M. Clark (+1942)". wrecksite.eu. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f "E. M. Clark" (PDF). Graveyard of the Atlantic Shipwreck Guides: 1–2 – via Monitor National Marine Sanctuary.

- ^ a b c d "E.M. Clark". Monitor National Marine Sanctuary. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

- ^ a b c d e f Visser, Auke. "Cape Hatteras Attack". Auke Visser's International Esso Tankers site. Retrieved July 29, 2025.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Listings" (PDF). Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 6/24/13 through 6/28/13. National Park Service. July 5, 2013.

- ^ "NPGallery Asset Detail". npgallery.nps.gov. Retrieved July 29, 2025.